Srebrenica: Prologue, Chapter 1, Section 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download PDF Van Tekst

In het land der blinden Willem Oltmans bron Willem Oltmans, In het land der blinden. Papieren tijger, Breda 2001 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/oltm003inhe01_01/colofon.php © 2015 dbnl / Willem Oltmans Stichting 2 voor Jozias van Aartsen Willem Oltmans, In het land der blinden 7 1 Start Op 10 augustus 1953 besteeg ik voor het eerst de lange trappen naar de bovenste verdieping van het gebouw van het Algemeen Handelsblad aan de Nieuwezijds Voorburgwal in Amsterdam om mijn leven als journalist te beginnen. Chef van de redactie buitenland was dr. Anton Constandse. Van 1946 tot en met 1948 had ik de opleiding voor de diplomatieke dienst gevolgd van het Nederlands Opleidings Instituut voor het Buitenland (NOIB) op Nijenrode. Van 1948 tot en met 1950 volgde ik op het Yale College in New Haven, Connecticut, de studie Political Science and International Relations. Inmiddels 25 jaar geworden twijfelde ik steeds meer aan een leven als ambtenaar van het Ministerie van Buitenlandse Zaken. Was ik niet een te vrijgevochten en te zelfstandig denkende vogel om zonder tegensputteren of mokken braaf Haagse opdrachten uit te voeren waar ik het wellicht faliekant mee oneens zou zijn? Van een dergelijke incompatibilité d'humeurs zou immers alleen maar gedonder kunnen komen. Op het Yale College had ik in dit verband al het een en ander meegemaakt. In 1949 was ik tot praeses van de Yale International Club gekozen, een organisatie voor de in New Haven studerende buitenlandse studenten. Nederland knokte in die dagen onder de noemer van ‘politionele acties’ tegen Indonesië. Ik nodigde ambassadeur F.C.A. -

Annual Report 2013 Headlines of 2013 President’S Message

FOOD & BEVERAGE SPORT & RECREATION EVENTS & ENTERTAINMENT ANNUAL REPORT 2013 HEADLINES OF 2013 PRESIDENT’s MESSAGE SO YOU THINK YOU CAN DANCE RIFE WITH CAN-CON. B5 A4 Sunday, April 21, 2013 Leader-Post • leaderpost.com Sunday, April 21, 2013 A5 More than 180 rigging points with HD over 4,535 kg of equipment overhead mobile Another Record Year Governance with 13 150 60 strobe light fixtures, 731 metres cameras speakers of lighting trusses, 720,000 watts in 14 of lighting power and 587 moving SOUND clusters head lighting fixtures The year 2013 will go down as In 2012, we finally made application to the Province of &VISION artsBREAKING NEWS& AT L EA D ERlifePOST.COM Canada’s annual music awards yet another record year for Evraz Saskatchewan to step away from our original (1907) Act. extravaganza — to be hosted at SECTION B TUESDAY, AUGUST 13, 2013 Regina’s Brandt Centre tonight — requires a monumental effort in Place (operated by The Regina It has served us well for over a century, but had become planning and logistics. Here’s last year’s stage with some of the key numbers for this year’s event. Exhibition Association Limited): outdated for our current business activity and contemporary Design by Juris Graney 1,800 LED BRYAN SCHLOSSER/Sunday Post • Record revenues of $34.8M. governance model. In 2014, The Regina Exhibition panels Crews prepare the elaborate stage for the Juno Awards being held at the Brandt Centre tonight. on 13 suspended Setting the stage towers • Three extraordinary high Association Limited will continue under The Non-profit -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Draaien om de werkelijkheid: rapport over het antropologisch werk van prof. em. M.M.G. Bax Baud, M.; Legêne, S.; Pels, P. Publication date 2013 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Baud, M., Legêne, S., & Pels, P. (2013). Draaien om de werkelijkheid: rapport over het antropologisch werk van prof. em. M.M.G. Bax. Vrije Universiteit. http://www.vu.nl/nl/Images/20130910_RapportBax_tcm9-356928.pdf General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 Draaien om de werkelijkheid Rapport over het antropologisch werk van prof. em. M.M.G. Bax Michiel Baud Susan Legêne Peter Pels -

OUR GUARANTEE You Must Be Satisfied with Any Item Purchased from This Catalog Or Return It Within 60 Days for a Full Refund

Edward R. Hamilton Bookseller Company • Falls Village, Connecticut February 26, 2016 These items are in limited supply and at these prices may sell out fast. DVD 1836234 ANCIENT 7623992 GIRL, MAKE YOUR MONEY 6545157 BERNSTEIN’S PROPHETS/JESUS’ SILENT GROW! A Sister’s Guide to ORCHESTRAL MUSIC: An Owner’s YEARS. Encounters with the Protecting Your Future and Enriching Manual. By David Hurwitz. In this Unexplained takes viewers on a journey Your Life. By G. Bridgforth & G. listener’s guide, and in conjunction through the greatest religious mysteries Perry-Mason. Delivers sister-to-sister with the accompanying 17-track audio of the ages. This set includes two advice on how to master the stock CD, Hurwitz presents all of Leonard investigations: Could Ancient Prophets market, grow your income, and start Bernstein’s significant concert works See the Future? and Jesus’ Silent Years: investing in your biggest asset—you. in a detailed but approachable way. Where Was Jesus All Those Years? 88 Book Club Edition. 244 pages. 131 pages. Amadeus. Paperbound. minutes SOLDon two DVDs. TLN. OU $7.95T Broadway. Orig. Pub. at $19.95 $2.95 Pub. at $24.99SOLD OU $2.95T 2719711 THE ECSTASY OF DEFEAT: 756810X YOUR INCREDIBLE CAT: 6410421 THE MAMMOTH BOOK OF Sports Reporting at Its Finest by the Understanding the Secret Powers ANTARCTIC JOURNEYS. Ed. by Jon Editors of The Onion. From painfully of Your Pet. By David Greene. E. Lewis. Collects a heart-pounding obvious steroid revelations to superstars Interweaves scientific studies, history, assortment of 32 true, first-hand who announce trades in over-the-top TV mythology, and the claims of accounts of death-defying expeditions specials, the world of sports often seems cat-owners and concludes that cats in the earth’s southernmost wilderness. -

Pilgrimage, Spatial Interaction, and Memory at Three Marian Sites

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2016 Pilgrimage, Spatial Interaction, and Memory at Three Marian Sites Katherine Rousseau University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Rousseau, Katherine, "Pilgrimage, Spatial Interaction, and Memory at Three Marian Sites" (2016). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1129. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1129 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Pilgrimage, Spatial Interaction, and Memory at Three Marian Sites __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the University of Denver and the Iliff School of Theology Joint PhD Program University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by T.K. Rousseau June 2016 Advisor: Scott Montgomery ©Copyright by T.K. Rousseau 2016 All Rights Reserved Author: T.K. Rousseau Title: Pilgrimage, Spatial Interaction, and Memory at Three Marian Sites Advisor: Scott Montgomery Degree Date: June 2016 Abstract Global mediation, communication, and technology facilitate pilgrimage places with porous boundaries, and the dynamics of porousness are complex and varied. Three Marian, Catholic pilgrimage places demonstrate the potential for variation in porous boundaries: Chartres cathedral; the Marian apparition location of Medjugorje; and the House of the Virgin Mary near Ephesus. -

The Pink Swastika

THE PINK SWASTIKA Homosexuality in the Nazi Party by Scott Lively and Kevin Abrams 1 Reviewers Praise The Pink Swastika “The Pink Swastika: Homosexuality in the Nazi Party is a thoroughly researched, eminently readable, demolition of the “gay” myth, symbolized by the pink triangle, that the Nazis were anti- homosexual. The deep roots of homosexuality in the Nazi party are brilliantly exposed . .” Dr. Howard Hurwitz, Family Defense Council “As a Jewish scholar who lost hundreds of her family in the Holocaust, I welcome The Pink Swastika as courageous and timely . Lively and Abrams reveal the reigning “gay history” as revisionist and expose the supermale German homosexuals for what they were - Nazi brutes, not Nazi victims.” Dr. Judith Reisman, Institute for Media Education “The Pink Swastika is a tremendously valuable book, replete with impressive documentation presented in a compelling fashion.” William Grigg, The New American “...exposes numerous lies, and tears away many myths. Essential reading, it is a formidable boulder cast into the path of the onrushing homosexual express...” Stan Goodenough, Middle East Intelligence Digest “The Pink Swastika is a powerful exposure of pre-World War II Germany and its quest for reviving and imitating a Hellenistic-paganistic idea of homo-eroticism and militarism.” Dr. Mordechai Nisan, Hebrew University of Jerusalem “Lively and Abrams call attention to what Hitlerism really stood for, abortion, euthanasia, hatred of Jews, and, very emphatically, homosexuality. This many of us knew in the 1930’s; it was common knowledge, but now it is denied...” R. J. Rushdoony, The Chalcedon Report “...a treasury of knowledge for anyone who wants to know what really happened during the Jewish Holocaust...” Norman Saville, News of All Israel “...Scott Lively and Kevin Abrams have done America a great service...” Col. -

Draaien Om De Werkelijkheid

Draaien om de werkelijkheid Rapport over het antropologisch werk van prof. em. M.M.G. Bax Michiel Baud Susan Legêne Peter Pels Amsterdam, 9 september 2013 1 2 Inhoudsopgave Preambule Inleiding 1 De beschuldigingen aan het adres van Mart Bax 2 Neerdonk en het Brabants onderzoek 3 Medjugorje en het Bosnisch onderzoek 4 De publicaties van Bax 5 Conclusies van de commissie 6 Context en consequenties Bijlagen: 1 Opdracht aan de commissie 2 Bronnen en geraadpleegde literatuur 3 Lijst van opgegeven publicaties van Mart Bax met verschenen en niet verschenen titels 4 Geordend overzicht Medjugorje‐publicaties 3 4 Preambule De zaak die centraal staat in dit rapport is pijnlijk voor alle betrokkenen. Het gaat in de eerste plaats om de reputatie van een Nederlandse antropoloog, maar daarmee ook om een antropologische discipline en haar methodologie. Het betreft bovendien, niet onbelangrijk, een heel scala van menselijke en collegiale verhoudingen in de academische omgeving die gebaseerd zijn op een verwachting van eerlijkheid en transparantie. Het gaat, tenslotte, ook om instituties en hun functioneren, niet alleen de universiteit en de financiering van en controle op academisch onderzoek, maar ook het systeem van visitatiecommissies, peer‐reviewing en wetenschappelijk publiceren. Academische verhoudingen zijn gebaseerd op vertrouwen in de wetenschappelijke eerlijkheid van alle partijen. Twijfel over deze cruciale elementen, van welke aard ook, laat diepe sporen na. Enkele recente gevallen van wetenschappelijke fraude hebben laten zien hoe verreikend de gevolgen – maatschappelijk en academisch – kunnen zijn als dit vertrouwen geschaad wordt en wetenschappelijke integriteit niet meer vanzelfsprekend is. 5 6 Inleiding Dit rapport vindt zijn oorsprong in beschuldigingen van wetenschappelijk wangedrag aan het adres van prof. -

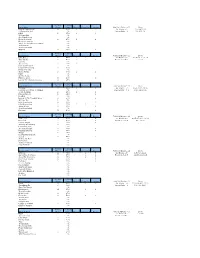

Up to Here # Times Played % Shows Played Opened Closed Set Encore

# Times % Shows Up To Here Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 11 Show Blow at High Dough 9 60% 2 3 Set Blocks = 6 1,5,7,9,12,14 I'll Believe In You 0% Encore Sets = 5 2,6,8,11,15 NOIS 10 67% 1 4 38 Years Old 0% She Didn't Know 0% Boots Or Hearts 10 67% 2 4 Everytime You Go 0% When The Weight Comes Down 0% Trickle Down 0% Another Midnight 0% Opiated 8 53% 1 2 # Times % Shows Road Apples Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 11 Show Little Bones 8 53% 1 1 Set Blocks = 8 1,2,4,6,8,10,12,15 Twist My Arm 8 53% 1 2 1 Encore Sets = 3 3,9,13 Cordelia 0% The Luxury 5 33% 1 Born In The Water 0% Long Time Running 4 27% Bring It All Back 0% Three Pistols 6 40% 1 1 Fight 0% On The Verge 0% Fiddler's Green 6 40% 3 Last Of The Unplucked Gems 4 27% # Times % Shows Fully Completely Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 13 Show Courage 10 67% 2 4 Set Blocks = 7 3,5,8,10,11,13,15 Looking For A Place To Happen 0% Encore Sets = 6.1 1,2,4,7,9,14,15 100th Meridian 10 67% 2 3 Pigeon Camera 2 13% 1 Lionized 0% Locked In The Trunk Of A Car 3 20% 2 We'll Go Too 1 7% Fully Completely 4 27% 3 Fifty Mission Cap 5 33% 1 1 Wheat Kings 8 53% 4 The Wherewithal 0% Eldorado 3 20% 1 # Times % Shows Day For Night Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 13 Show Grace, Too 13 87% 1 4 Set Blocks = 9 2,3,5,6,7,9,11,13,14 Daredevil 7 47% 1 Encore Sets = 4 4,10,12,15 Greasy Jungle 5 33% 1 Yawning Or Snarling 2 13% Fire In The Hole 0% So Hard Done By 7 47% 1 Nautical Disaster 4 27% 2 Thugs 2 13% Inevitability Of Death 0% Scared 7 47% 2 An Inch An Hour 0% Emergency 0% Titanic Terrarium 0% Impossibilium 0% # Times % Shows Trouble At The Henhouse Played Played Opened Closed Set Encore Total Set Blocks = 13 Show Giftshop 11 73% 1 5 Set Blocks = 6 3,5,7,10,12,14 Springtime In Vienna 7 47% 1 1 Encore Sets = 7 1,4,6,8,11,13,15 Ahead By A Century 13 87% 2 7 Don't Wake Daddy 4 27% 1 Flamenco 5 33% 2 700 Ft. -

A Local Contribution to the Ethnography of the War in Bosnia-Herzegovina Bax, M.M.G

VU Research Portal Planned policy or primitive balkanism? A local contribution to the ethnography of the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina Bax, M.M.G. published in Ethnos 2000 DOI (link to publisher) 10.1080/00141840050198018 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Bax, M. M. G. (2000). Planned policy or primitive balkanism? A local contribution to the ethnography of the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Ethnos, 65(3), 2-24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141840050198018 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Planned Policy or Primitive Balkanism? 3 1 7 Planned Policy or Primitive Balkanism? A Local Contribution to the Ethnography of the War in Bosnia-Herzegovina Mart Bax Free University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands abstract There is a tendency among social scientists and others to interpret the recent war and the related ‘ethnic cleansing’ in Bosnia-Herzegovina in terms of a poli- tical policy carefully orchestrated from above and systematically carried out. -

Modern Humanism in the Netherlands

3 Modern Humanism in the Netherlands Peter Derkx Erasmus of Rotterdam, who died in 1536, may very weU be the most famous Outch humanist. I This chapter deals with the much less well-known develop ment of modern Dutch humanism in the period aftel' 1850. Erasmus, with his conciliatory and moderate attitude and his non-dogmatic, primarily ethical type of Christianity, remains a major inflllence on Dutch humanism, but, for that matter, Dutch humanism is stamped by the overall history of the Netherlands. In terms of geography, the Netherlands is a very small, densely populated coun try in Northwest Europe. lts culture has been very much determined by the struggle against the water. More than a quarter of the country is below sea level and a number of major rivers flow into the sea near Rotterdam. In the second half of the sixteenth century, the Dutch started the revolt that made them inde pendent of the Spanish empire. In the seventeenth century, the Netherlands, es peciaLly Holland with the city of Amsterdam, was a major power in every sense. Before the British did sa, the Dutch ruled the world seas. The voe (United East India Company) was the world's largest trading company in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. International trade was and is very important for the Outch. According to same historians, the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic should be regarded as the first successful modern economy (De Vries & Van der Woude 1997). The Dutch Golden Age manifested itself not only in an unprece dented increase in (very unequally distributed) wealth, but also in a politicaLly, religiously and intellectllally pluralistic and tolerant atmosphere, characterized bya large nllmber of publishing houses. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title Title (Reba McEntire & Vince Gill) 2 Pac 2 Pac The Heart Won't Lie High Till I Die When My Homies Call 10 Things I Hate About You Hit 'Em Up Words Of Wisdom Dazz Holler If Ya' Hear Me Young Black Male 10 Years How Do U Want It 2 Unlimited Wasteland How Long Will They Mourn Me? Get Ready For This 10,000 Maniacs I Ain't Mad At Cha 3 Days Grace Because The Night Belongs To I Came To Bring The Pain Pain Lovers I Don't Give A Fuck 3 Doors Down 100 Songs For Kids I Get Around Away From The Sun How Much Is That Doggy In The I'd Rather Be Your Nigga Be Like That Window If My Homie Calls Be Like That (Edit) You Are My Sunshine Keep Ya Head Up Behind Those Eyes 10000 Maniacs - Life Goes On Better Life Because The Night Belongs To Lost Soulz By My Side Lovers Me Against The World Down Poison 112 N.*.*.*.*. (Never Ignorant About Duck And Run Anywhere {Booty Bass Remix}{Ft. Getting Goals Accomplished) Here By Me Lil' Zane} One Day At A Time [Em's Version] Here Without You Dance With Me Outlaw (Feat Dramacydal) It's Not Me Peaches And Cream Panther Power Kryptonite U Already Know Pat Time Mutha Kryptonite (Acoustic) 12 Stones Picture Me Rollin' Life Of My Own The Way I Feel Rebel Of The Underground Loser 2 Live Crew Rebel Of The Underground My World Tootsie Roll Runnin' (Dying To Live) Never Will I Break 2 Pac Same Song Not Enough 2 Of Amerikaz Most Wanted Secretz Of War Smack Abitionz As A Ryder She's So Scandalous So Far Down All About U Smile So I Need You Baby Don't Cry So Many Tears 30 Seconds To Mars Brenda's Got A Baby Something Wicked The Kill Bury Me A G Soulja's Story 311 California Love [Original Version] Starin' Through My Rear View Amber Call The Cops When You See 2 Str8 Ballin' Pac Come Original Temptations Changes Feels So Good Tha' Lunatic Check Out Time (Feat Kurupt) Wobble Wobble The Realist Killaz Dear Mama 38 Special Thug Passion Death Around The Corner Hold On Loosley To Live & Die In L.A. -

DOWNLOAD Humanists International 1952-2002

International Humanist and Ethical Union 1952-2002 Copyright © 2002 by De Tijdstroom uitgeverij. Republished at www.iheu.org with permission. Humanistics Library Copyright © 2002 by De Tijdstroom uitgeverij. Republished at www.iheu.org with permission. Bert Gasenbeek and Babu Gogineni (eds.) International Humanist and Ethical Union 1952-2002 Past, present and future De Tijdstroom uitgeverij, Utrecht Copyright © 2002 by De Tijdstroom uitgeverij. Republished at www.iheu.org with permission. Copyright © 2002 by De Tijdstroom uitgeverij. Cover design: Cees Brake bNO, Enschede. Front cover photograph: ‘Voyage vers l’infini’, by Etoundi Essamba (1984). Cartoons: Mr. Mohan (India). All rights reserved, including those of translation into foreign languages. Printed in the Netherlands. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form—by photo- print, microfilm, or any other means—or transmitted or translated into a machine language without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, contact De Tijdstroom uitgeverij BV, Asschatterweg 44, 3831 JW Leusden, the Netherlands, [email protected]. isbn 90 5898 041 3 nur 730, 740 Copyright © 2002 by De Tijdstroom uitgeverij. Republished at www.iheu.org with permission. Contents Preface 7 Humanism for the world. The IHEU in a nutshell 9 Babu Gogineni Past From theory to practice—a history of IHEU 1952-2002 15 Hans van Deukeren 1850-1952: The road to the founding congress 16 1952-1962: Years of construction 28 1962-1975: High expectations, lean years 40 1975-1989: From imaginative consolidation to bright vistas 61 1989-2002: Clashes and resurrection 79 Conclusion 102 Sources and suggestions for further reading 104 Present Humanism and ketchup, or the future of Humanism 106 Babu Gogineni The future of international Humanism and the IHEU 112 Levi Fragell Future How to grow an elephant? 122 Andrzej Dominiczak Copyright © 2002 by De Tijdstroom uitgeverij.