Sharing Water and Benefits in Transboundary River Basins” by D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 3 Transboundary River Basins Indicator Assessment © USDA/Flickr

TRANSBOUNDARY RIVER BASINS INDICATOR ASSESSMENT Chapter 3 Transboundary River Basins Indicator Assessment © USDA/flickr 23 TRANSBOUNDARY RIVER BASINS: STATUS AND TRENDS Chapter 3.1 Socioeconomics Lead Authors Alex de Sherbinin (Center for International Earth Science Information Network, Columbia University). Contributing Authors Valentina Mara, Malanding Jaiteh, Marc Levy (Center for International Earth Science Information Network, Columbia University). Chapter Citation: de Sherbinin, A., Mara, V., Jaiteh, M., Levy, M. (2016). Chapter 3.1: Socioeconomics. In UNEP-DHI and UNEP (2016). Transboundary River Basins: Status and Trends. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, pp. 25–46. Chapter 3.2 Water Quantity Lead Authors Martina Flörke, Christof Schneider (Center for Environmental Systems Research, University of Kassel); Pamela Green, Charles Vörösmarty (Environmental CrossRoads Initiative, City University of New York) Chapter Citation: Flörke, M., Green, P., Schneider, C., Vörösmarty, C. (2016). Chapter 3.2: Water Quantity. In UNEP-DHI and UNEP (2016). Transboundary River Basins: Status and Trends. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, pp. 47–72. Chapter 3.3 Water Quality Lead Authors Sybil Seitzinger (International Geosphere Biosphere Programme); Emilio Mayorga (University of Washington); Maija Bertule (UNEP-DHI). Contributing Authors Carolien Kroeze (Wageningen UR); Paul Glennie (UNEP-DHI). Chapter Citation: Seitzinger, S., Bertule, M., Mayorga, E., Kroeze, C., Glennie, P. (2016). Chapter 3.3: Water Quality. In UNEP-DHI and UNEP (2016). Transboundary River Basins: Status and Trends. United Nations Environment Programme, Nairobi, pp. 73–86. Chapter 3.4 Ecosystems Lead Authors Pamela Green, Charles Vörösmarty (Environmental CrossRoads Initiative, City University of New York); Kevin Smith, Stefano Barchiesi (IUCN). Contributing Authors David Allen, James Dalton, William Darwall, (IUCN); Irina Dopson (City University of New York) Chapter Citation: Green, P., Smith, K., Barchiesi, S., Vörösmarty, C., Darwall, W., Allen, D., Dalton, J., Dopson, I. -

Troubled Waters: Climate Change, Hydropolitics, And

Troubled Waters Climate Change, Hydropolitics, and Transboundary Resources David Michel Amit Pandya Editors Copyright © 2009 The Henry L. Stimson Center ISBN: 978-0-9821935-2-5 Cover photos: Les Penuries D’eau Pourraient Tripler Avec le Rechauffement, India © 2006 STRDEL/AFP/Getty Images; 2007-BG-Noorani-0505, Bangladesh, River Bleeds Black Series © 2007 Shehzad Noorani Cover design by Free Range Studios Book design/layout by Nita Congress All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior written consent from The Henry L. Stimson Center. The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street, NW, 12th Floor Washington, DC 20036 Telephone: 202.223.5956 Fax: 202.238.9604 www.stimson.org Contents Preface ..................................................................................................................................v Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................. vii Introduction ........................................................................................................................ ix Climate Change and Water: Examining the Interlinkages ...................................................1 Jayashree Vivekanandan and Sreeja Nair Perspectives from the Regions South Asian Perspectives on Climate Change and Water Policy .......................................17 Ashok Jaitly Climate Insecurity in Southeast Asia: Designing Policies to Reduce Vulnerabilities .......33 Khairulmaini -

Memorial for the European Union

Memorial on Behalf of the European Union (EU) INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE REQUEST FOR AN ADVISORY OPINION CONCERNING FRESHWATER RIGHTS UNDER INTERNATIONAL LAW IN RELATION TO THE POTENTIAL LEGAL PERSONALITY OF RIVERS AND THE CLIMATE CRISIS MEMORIAL FOR THE EUROPEAN UNION THE 1st WCEL INTERNATIONAL WATER JUSTICE MOOT COURT AT THE CONFERENCE OF JUDGES AND PROSECUTORS ON WATER JUSTICE DURING THE 8th WORLD WATER FORUM IN BRASÍLIA, BRAZIL MARCH 2018 AGENT FOR THE EUROPEAN UNION: MATIJA KAJIĆ, LL.M, UTRECHT UNIVERSITY ADVISOR: ANOESKA BUIJZE 1st WCEL International Water Justice Moot Court – 8th World Water Forum – Brasília The agents and organizations in this moot court are participating for educational purposes only and have no actual attorney client relationship. 1 Memorial on Behalf of the European Union (EU) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Anoeska Buijze, Assistant Professor of Administrative Law at Utrecht University, the Netherlands. Hendrik Schoukens, Post-Doc staff member at the University of Ghent, assisting with the courses ‘Moot Court Public International Law’ and ‘Diplomatic Law’. Work of researchers at the Utrecht Centre for Water, Oceans and Sustainability Law. Work of researchers at RENFORCE (the Utrecht Centre for Regulation and Enforcement in Europe). 1st WCEL International Water Justice Moot Court – 8th World Water Forum – Brasília The agents and organizations in this moot court are participating for educational purposes only and have no actual attorney client relationship. 2 Memorial on Behalf of the European Union (EU) I. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 INDEX OF AUTHORITIES 4 II. STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION 7 III. PROBLEM PRESENTED 8 IV. IN CONTEXT: EUROPEAN UNION 10 V. -

Climate Change Implications on Transboundary Water Management

Master thesis in Sustainable Development 281 Examensarbete i Hållbar utveckling Climate change implications on transboundary water management in the Jordan River Basin: A Case Study of the Jordan River Basin and the transboundary agreements between riparians Israel, Palestine and Jordan Maisa Young DEPARTMENT OF EARTH SCIENCES INSTITUTIONEN FÖR GEOVETENSKAPER Master thesis in Sustainable Development 281 Examensarbete i Hållbar utveckling Climate change implications on transboundary water management in the Jordan River Basin: A Case Study of the Jordan River Basin and the transboundary agreements between riparians Israel, Palestine and Jordan Maisa Young Supervisor: Ashok Swain Evaluator: Neil Powell Copyright © Maisa Young and the Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University Published at Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University (www.geo.uu.se), Uppsala, 2015 Content 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Climate change and water scarcity ................................................................................................................ 1 1.1.1. Transboundary Water Management ............................................................................................................ 2 1.1.2. The Middle East .......................................................................................................................................... 2 1.1.3. The Jordan River Basin .............................................................................................................................. -

Transboundary Water Conflict Resolution Mechanisms

water Review Transboundary Water Conflict Resolution Mechanisms: Substitutes or Complements Ahmed Tayia Centre for Environmental Policy (CEP), Imperial College London, London SW7 1NE, UK; [email protected]; Tel.: +44-7493095757 Received: 21 May 2019; Accepted: 21 June 2019; Published: 28 June 2019 Abstract: This paper examines the transboundary water resources conflict resolution mechanisms. Various academic fields have provided conflict resolution mechanisms that could be used to analyse transboundary water conflicts. These mechanisms include social planner, water market, game theory, static and dynamic systems engineering models, and negotiation analyses. These mechanisms share some common characteristic features. This similarity has led to a general belief that these mechanisms are competitive substitutes. However, closer examination by this research reveals that these mechanisms have more complementarity than similarity. This complementarity permits researchers and practitioners to combine any two or more of them to develop more comprehensive mechanisms with stronger analytical capacity to analyse the different elements of the process of transboundary water conflict resolution. Keywords: transboundary water conflict resolution mechanism; hydro-diplomacy; systems engineering models; social planner; water market; game theory; hydropolitics and critical hydropolitics; hydro-hegemony; Transboundary Waters Interaction Nexus (TWINS); Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR); virtual water 1. Introduction Management of Transboundary water resources is expected be one of the biggest challenges facing human development over the next decades [1]. In general, transboundary water resources can describe water shared across political, economic, or social boundaries [2]. Shared water resources have been always a potential source of competition. The English language, as well as many other Latin-rooted languages, reflects this historical relation between shared rivers and competition, as it uses the word “rival” to refer to a competitor against others. -

1 Testimony Before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review

Date of the hearing: January 26, 2012. Title of the hearing: China’s Global Quest for Resources and Implications for the United States Name of panelist: Brahma Chellaney Panelist’s title and organization: Professor of Strategic Studies, Center for Policy Research, New Delhi. Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission China has pursued an aggressive strategy to secure (and even lock up) supplies of strategic resources like water, energy and mineral ores. Gaining access to or control of resources has been a key driver of its foreign and domestic policies. China, with the world’s most resource-hungry economy, is pursuing the world’s most-assertive policies to gain control of important resources. Much of the international attention on China’s resource strategy has focused on its scramble to secure supplies of hydrocarbons and mineral ores. Such attention is justified by the fact that China is seeking to conserve its own mineral resources and rely on imports. For example, China, a major steel consumer, has substantial reserves of iron ore, yet it has banned exports of this commodity. It actually encourages its own steel producers to import iron ore. China, in fact, has emerged as the largest importer of iron ore, accounting for a third of all global imports. India, in contrast, remains a major exporter of iron ore to China, although the latter has iron-ore deposits more than two-and-half times that of India. But while buying up mineral resources in foreign lands, China now supplies, according to one estimate, about 95 per cent of the world’s consumption of rare earths — a precious group of minerals vital to high- technology industry, such as miniaturized electronics, computer disk drives, display screens, missile guidance, pollution-control catalysts, and advanced materials. -

The Importance of Cooperation Between Transboundary River

United Nations International Centre Educational, Scientific and for Water Resources and Global Change Cultural Organization under the auspices of UNESCO Jennifer Cruz - Political Science Major at the Notre Dame University of Maryland, USA The Importance of Cooperation Between Transboundary River Countries United Nations International Centre Educational, Scientific and for Water Resources and Global Change Cultural Organization under the auspices of UNESCO The Importance of Cooperation Between Transboundary River Countries This work was composed during an internship at the International Centre for Water Resources and Global Change (ICWRGC) located in Koblenz, Germany, during a span of 3 months, from May to August. Taking up the publication from Molnar, Kata, et al. (2017), this internship work focuses on cooperation between countries. It points out the importance of cooperation especially within transboundary river countries using the Nile and the Rhine River asexamples where cooperation has developed over time. Author: Jennifer Cruz - Political Science Major at the Notre Dame University of Maryland, USA Acknowledgement for Support and Guidance: Harald Köthe, Supervisor of the internship Director of the International Centre for Water Resources and Global Change (ICWRGC), located in Koblenz, Germany. Dr. Susanne Schmeier Senior Lecturer in Water Law, Diplomacy and Transboundary Water Management at the IHE Delft Institute for Water Education, the Netherlands. Heide Jekel Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety, located in Bonn, Germany. Head of Division WR I 4 - Cooperation in International River Basins, Freshwater Management Conventions, International Freshwater Protection Law. Dr. Tabea Stötter and Dr. Laura Gangi International Commission for the Protection of the Rhine (ICPR) located in Koblenz, Germany. -

Communicating the Benefits of Transboundary Water Cooperation

Communicating the benefits of transboundary water cooperation Peter Easton Peter Easton BSc MSc • MSc Hydrogeology • 30 years experience in Europe, Middle East and Africa • Ministry of Water Resources, Oman 1990-95 • Coca-Cola, Water Resources Manager Europe 2005-2012 • Currently: independent consultant and contributor to Revolve Water Punting on the Okavanga Dec 2017 Revolve Water Communication and Events Special reports Quarterly sustainability magazine Content • Basic principles of good communication • Review of transboundary water bodies: type, scale, issues and risks • Brief real examples on benefits of communication: – Danube – Murray-Darling – Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania – India-Pakistan Communicating on technical subjects to a mixed and non-technical audience • Some: – Clarity – Plain language – Avoid jargon and acronyms (if must use, explain) – Keep it brief – Use clear illustrations and images – Be understood! Transboundary water bodies • Types – River basin – Lakes (and inland seas) – Groundwater bodies • Scale • Understanding issues and risks River basin Impacts mainly travel from upstream to downstream Scale of river basins Blue= transboundary river basin Green = transboundary river basin Lakes (and inland seas) Uganda Kenya Kazakhstan Lake Victoria Georgia Tanzania Tanzania Lake Tanganyika Iran DR Congo Turkmenistan Switzerland Zambia France • Circulation of water (and pollution) Lake Geneva / Lac Léman • Actions in the wider basin • Pollution, over abstraction Mediterranean basin The health of the Sea is dependent on how -

Handbook for Integrated Water Resources Management in Transboundary Basins of Rivers, Lakes and Aquifers

THE HANDBOOK FOR INTEGRATED WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT IN TRANSBOUNDARY BASINS OF RIVERS, LAKES AND AQUIFERS March 2012 GWP / INBO The drafting of this handbook was coordinated by The French Development Agency gave advice, did Christophe Brachet and Daniel Valensuela of the proofreading and financed the translation and International Office for Water (Permanent publication of this handbook. Technical Secretariat of the International Network of Basin Organizations) in partnership with The English translation was provided by Gisèle Patricia Wouters (GWP Technical Committee and Sine (IOWater/INBO). Dundee UNESCO-HELP Centre), Nataliya NIKIFOROVA (UNECE), Jose Luis Martin Bordes, The handbook can be downloaded from the Alice Aureli, Raya Marina Stephan, Neno Kukuric following websites: (UNESCO), Ivan Zavadsky (GEF) and Elisa Vargas Amelin (EVREN). www.inbo-news.org www.gwp.org The case studies were collected through INBO www.iowater.org and GWP networks, and from examples provided by the partners. Published in 2012. Traduction : Gisèle Sine. Mise en page et design : Scriptoria, FGgraphic/Franck Guihard. ISBN : 978-91-85321-85-8 (March 2012). THE HANDBOOK FOR INTEGRATED WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT IN TRANSBOUNDARY BASINS OF RIVERS, LAKES AND AQUIFERS www. inbo-news .org | www. gwp .org TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................................6 -

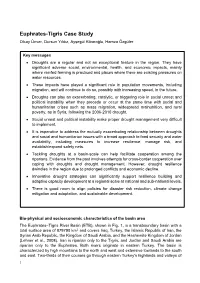

Euphrates-Tigris Case Study Olcay Ünver, Dursun Yıldız, Ayşegül Kibaroğlu, Hamza Özgüler

Euphrates-Tigris Case Study Olcay Ünver, Dursun Yıldız, Ayşegül Kibaroğlu, Hamza Özgüler Key messages • Droughts are a regular and not an exceptional feature in the region. They have significant adverse social, environmental, health, and economic impacts, mainly where rainfed farming is practiced and places where there are existing pressures on water resources. • These impacts have played a significant role in population movements, including migration, and will continue to do so, possibly with increasing speed, in the future. • Droughts can play an exacerbating, catalytic, or triggering role in social unrest and political instability when they precede or occur at the same time with social and humanitarian crises such as mass migration, widespread malnutrition, and rural poverty, as in Syria, following the 2006-2010 drought. • Social unrest and political instability make proper drought management very difficult to implement. • It is imperative to address the mutually exacerbating relationship between droughts and social and humanitarian issues with a broad approach to food security and water availability, including measures to increase resilience, manage risk, and establish/expand safety nets. • Tackling droughts at a basin-scale can help facilitate cooperation among the riparians. Evidence from the past involves attempts for cross-border cooperation over coping with droughts and drought management. However, drought resilience dwindles in the region due to prolonged conflicts and economic decline. • Innovative drought strategies can significantly support resilience building and adaptive capacity development at a regional scale at national and sub-national levels. • There is good room to align policies for disaster risk reduction, climate change mitigation and adaptation, and sustainable development. Bio-physical and socioeconomic characteristics of the basin area The Euphrates–Tigris River Basin (ETB), shown in Fig. -

Euphrates River Basin

Chapter 1 Euphrates River Basin INVENTORY OF SHARED WATER RESOURCES IN WESTERN ASIA (ONLINE VERSION) How to cite UN-ESCWA and BGR (United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia; Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe). 2013. Inventory of Shared Water Resources in Western Asia. Beirut. CHAPTER 1 - EUPHRATES RIVER BASIN Euphrates River Basin The Euphrates at the syrian-Turkish border, syria, 2009. source: adel samara. eXecutiVe suMMarY The Euphrates River is the longest river in last 70 years show a negative trend, indicating a Western asia. The river has three riparian decrease in mean annual flow to about 25 Bcm. countries, Iraq, syria and Turkey, and its basin The regulation of the Euphrates River is an is distributed among five countries with a total extreme example of how human intervention can estimated population of 23 million. impact a river regime. With the construction of most of the Euphrates stream-flow originates large water engineering structures in upstream from precipitation in the armenian Highlands; Turkey and syria, the Euphrates flow regime contributions by the remaining riparian has shifted towards less pronounced seasonal countries are generally small. In addition to variation. some intermittent streams, the sajur, Balikh Water use in the Euphrates Basin in Iraq, syria and Khabour are the main contributors to and Turkey focuses on irrigation, hydropower Euphrates flow in syria. and drinking water supply, with agriculture Historically, the natural annual flow of the consuming the largest share of water (more Euphrates at the syrian-Turkish border was than 70%). around 30 Bcm. However, data records over the 48 INVENTORY OF SHARED WATER RESOURCES IN WESTERN ASIA - PART I as a result, water quality has become a serious basin Facts issue on the Euphrates River: return flows from agricultural drainage cause salinity problems riParian COUNTRIES Iraq, syria, Turkey that are exacerbated along the river course. -

Transboundary Water Cooperation in Africa: the Case of the Nile Basin Initiative (Nbi)

TRANSBOUNDARY WATER COOPERATION IN AFRICA: THE CASE OF THE NILE BASIN INITIATIVE (NBI) Wondwosen TESHOME University of Vienna, Austria [email protected] Abstract The aim of this paper is to identify the economic, social and political benefits of the transboundary cooperation by using the Nile Bain Initiative (NBI) as a case study. It also attempts to ident ify the obstacles that hinder transboundary cooperation in the Nile Basin. The paper argues that the riparian states in the Nile Basin should work for “benefit-sharing” rather than “water-sharing” and this should be the basis for the transboundary cooperat ion. It also claims that implementing the concept of benefit-sharing would help in solving problems that are caused by divergent interests among the riparian states in the Nile basin and the up stream-down stream problems frequently manifested in the area. The paper concludes by suggesting the main points that have to be considered in transboundary cooperation. Keywords: “benefit-sharing”, Nile Basin Initiative, transboundary cooperation, “water- sharing.” JEL Classification: N57 , O 11 . 1. Introduction In Africa, there are many river basins and some of them are transboundary. One of the transboundary river basins that extend over the territories of several countries is the Nile River basin. The Nile river is the longest river in the world and the total area of the river basin is more than 3,349,000 Km 2 and the basin is a home to around 160 million people (with in the boundaries of the basin). In the ten countries that share the Nile’s water, about 300 million people live (UNESCO, 2006).