Download Legal Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Terrorist Trial Report Card: U.S. Edition – Appendix B

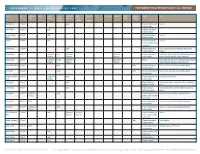

SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 – SEPTEMBER 11, 2006 TERRORIST TRIAL REPORT CARD: U.S. EDITION Name Date Commercial Drugs General General Immigration National Obstruction Other Racketeering Terrorism Violent Weapons Sentence Notes Fraud Fraud Criminal Violations Security of Crimes Violations Conspiracy Violations Investigation Khalid Al Draibi 12-Sep-01 Guilty 4 months imprisonment, 36 Deported months probation Sherif Khamis 13-Sep-01 Guilty 2.5 months imprisonment, 36 months probation Jean-Tony Antoine 14-Sep-01 Guilty 12 months imprisonment, Deported Oulai 24 months probation Atif Raza 17-Sep-01 Guilty 4.7 months imprisonment, Deported 36 months probation, $4,183 fine/restitution Francis Guagni 17-Sep-01 Guilty 20 months imprisonment, French national arrested at Canadian border with box cutter; 36 months probation Deported Ahmed Hannan 18-Sep-01 Acquitted or Guilty Acquitted or Acquitted or 6 months imprisonment, 24 Detroit Sleeper Cell Case (Karim Koubriti, Ahmed Hannan, Youssef Dismissed Dismissed Dismissed months probation Hmimssa, Abdel Ilah Elmardoudi, Farouk Ali-Haimoud) Karim Koubriti 18-Sep-01 Acquitted or Pending Acquitted or Acquitted or Pending Detroit Sleeper Cell Case (Karim Koubriti, Ahmed Hannan, Youssef Dismissed Dismissed Dismissed Hmimssa, Abdel Ilah Elmardoudi, Farouk Ali-Haimoud) Vincente Rafael Pierre 18-Sep-01 Guilty Guilty 24 months imprisonment, Pierre et al. (Vincente Rafael Pierre, Traci Elaine Upshur) 36 months probation Traci Upshur 18-Sep-01 Guilty Guilty 15 months imprisonment, 24 Pierre et al. (Vincente Rafael Pierre, -

Shariah: the Threat to America: an Exercise in Competitive Analysis

SHARIAH: THE THREAT TO AMERICA AN EXERCISE IN COMPETITIVE ANALYSIS REPORT OF TEAM ‘B’ II 1 Copyright © 2010 The Center for Security Policy All rights reserved. Shariah: The Threat to America (An Exercise in Competitive Analysis—Report of Team ‘B’ II) is published in the United States by the Center for Security Policy Press, a division of the Center for Security Policy. THE CENTER FOR SECURITY POLICY 1901 Pennsylvania Avenue, Suite 201 Washington, DC 20006 Phone: (202) 835-9077 Email: [email protected] For more information, please see securefreedom.org ISBN 978-0-9822947-6-5 Book design by David Reaboi. PREFACE This study is the result of months of analysis, discussion and drafting by a group of top security policy experts concerned with the preeminent totalitarian threat of our time: the legal-political-military doctrine known within Islam as “shariah.” It is designed to provide a comprehensive and articulate “second opinion” on the official characterizations and assessments of this threat as put forth by the United States government. The authors, under the sponsorship of the Center for Security Policy, have modeled this work on an earlier “exercise in competitive analysis” which came to be known as the “Team B” Report. That 1976 document challenged the then-prevailing official U.S. government intelligence estimates of the intentions and offensive capabilities of the Soviet Union and the policy known as “détente” that such estimates ostensi- bly justified. Unlike its predecessor, which a group of independent security policy professionals conducted at the request and under the sponsorship of the Director of Central Intelligence, George H.W. -

BOP-CTU-2.Pdf

UNCLASSIFIED // FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY / LAW ENFORCEM ENT SENSITIVE FEDERAL BUREAU OF PRISONS COUNTER TERRORISM UNIT August 24, 2009 INTELLIGENCE SUMMARY INTELLIGENCE ANALYSIS AND LANGUAGE TRANSLATION FOR INTERNATIONAL AND DOMESTIC TERRORIST INMATES (09-016) LAW ENFORCEMENT SENSITIVE: This information is the property of the Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) and may be distributed to state or local government law enforcement officials with a need-to-know. Further distribution without BOP authorization is prohibited. Precautions should be taken to ensure this information is stored and/or destroyed in a manner which precludes unauthorized access. International Terrorism Name Reg. No. Facl COJ STG Affiliations JONES, Royal 04935-046 MAR MT Bloods A Radicalization and CMU Int Terr C Recruitment Comm Cat 2 Name Reg. No. Facl COJ STG Affiliations WASHINGTON, Levar 29205-112 MAR CAC Dom Terr A Jam'iyyat Ul-Islam CMU Crips A Is-Saheeh (JIS) On August 10, 2009, inmate Jones authored correspondence to his daughter, Brittany Jones, 3719 45th Avenue, Sacramento, CA, 95824. The correspondence consisted of an eight page, handwritten letter which detailed recent issues among the inmate Muslim population in MAR CMU which resulted in a physical altercation between inmates Washington and Imran Mandhai, Reg. No. 56175-004. Inmate Jones indicated differing religious ideologies among the inmate Muslim population in MAR CMU were a contributing factor to the altercation involving inmate UNCLASSIFIED // FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY / LAW ENFORCEM ENT SENSITIVE Page 1 of 45 UNCLASSIFIED // FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY / LAW ENFORCEM ENT SENSITIVE Washington. Several inmates described a typical Islamic hierarchy which had developed among the Muslim community. -

KARIN J. IMMERGUT, OSB #96314 United States Attorney District of Oregon CHARLES F

KARIN J. IMMERGUT, OSB #96314 United States Attorney District of Oregon CHARLES F. GORDER, JR., OSB #91287 PAMALA R. HOLSINGER, OSB #89263 DAVID L. ATKINSON, OSB #75021 Assistant United States Attorneys 1000 S.W. Third Avenue, Suite 600 Portland, OR 97204-2024 Telephone: (503) 727-1000 Facsimile: (503) 727-1117 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF OREGON UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ) ) No. CR 02-399-JO v. ) ) JEFFREY LEON BATTLE, and ) GOVERNMENT’S PATRICE LUMUMBA FORD, ) SENTENCING MEMORANDUM ) Defendants. ) The United States of America, by Karin J. Immergut, United States Attorney for the District of Oregon, and Charles F. Gorder, Jr., Pamala R. Holsinger, and David L. Atkinson, Assistant United States Attorneys, respectfully submits this memorandum for the sentencings of defendants Battle and Ford which are currently set for Monday, November 24, 2003 at 9:00 a.m. The government is unaware of any disputed areas for the sentencing hearing with regard to the applicable guideline calculation and the ultimate sentence. The government and defendants agree, and the Probation Office concurs, that the defendants’ total offense level is 37 (Level 43 under U.S.S.G. § 2M1.1(a)(1) - Treason, minus 3 for conspiracy, minus 3 for acceptance of responsibility), defendants’ criminal history category is I, and the resulting guideline range is 210 to 262 months. Pursuant to the plea agreement between the parties and based upon the facts and evidence set forth below, the government requests a sentence of 216 months (18 years). STATEMENT OF FACTS This prosecution involved six Oregon residents who beginning as early as January 2001 began training themselves to fight in a so-called “jihad” somewhere in the world. -

Pistole Statement

Statement of John S. Pistole Executive Assistant Director for Counterterrorism/Counterintelligence Federal Bureau of Investigation before the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks upon the United States April 14, 2004 Chairman Kean, Vice Chairman Hamilton, and members of the Commission, thank you for this opportunity to appear before you and the American people today to discuss the FBI’s Counterterrorism mission. I am honored today to speak to you on behalf of the dedicated men and women of the FBI who are working around the clock and all over the globe to combat terrorism. The FBI remains committed to fighting the threats posed by terrorism. But by no means do we fight this battle alone. I want to take a moment to thank our law enforcement and Intelligence Community partners, both domestic and international, for their invaluable assistance and support. I also thank this Commission. The FBI appreciates your tremendous efforts to make recommendations that will help the FBI evolve to meet and defeat terrorist threats. We will continue to work closely with you and your staff to provide access to FBI personnel and information, for the purpose of ultimately strengthening the security of our Nation. To the victims and family members that suffer as a result of the horrific attacks of September 11, 2001--and all acts of terrorism--the FBI has been heartened by your gratitude and mindful of your criticism. Under Director Mueller's leadership, the FBI has not merely begun a process of considered review--it has engaged in an unprecedented transformation. Today, the FBI is better positioned to fulfill its highest priority: “to Protect the United States from Terrorist attack.” The FBI employs a multifaceted approach in order to accomplish its mission. -

„Homegrown Terrorism“ in Den Vereinigten Staaten: Bedrohung, Ursachen Und Prävention Daveed Gartenstein-Ross

ISLAMISTISCHER TERRORISMUS IN DEN USA „Homegrown Terrorism“ in den Vereinigten Staaten: Bedrohung, Ursachen und Prävention Daveed Gartenstein-Ross zentrum der Nationalgarde in Little Neuheit des Phänomens und nehmen In den USA werden immer mehr dschiha- Rock (Arkansas).1 Der Terrorismus-Ex- dadurch eine ahistorische Perspektive distische Anschläge von Männern und perte von CNN, Peter Bergen, schloss ein. Wenn man das Konzept des „Ho- Frauen verübt, die in Nordamerika gebo- hieraus im Dezember 2009, dass eine megrown Terrorism“ aber nicht auf isla- ren sind oder sozialisiert wurden. Da- „Zunahme des Homegrown Terrorism mistische Anschläge begrenzt und län- veed Gartenstein-Ross setzt sich mit dem nicht geleugnet werden kann.“2 gere Zeiträume in den Blick nimmt, wird Problem des „Homegrown Terrorism“ in Manchmal halten solche spontanen Ein- schnell deutlich, dass es beispielsweise den USA auseinander. Er erörtert zu- schätzungen, die schnell verallgemei- in den 1970er Jahren deutlich mehr An- nächst die Frage, ob tatsächlich vermehrt nert und zur öffentlichen Meinung wer- schläge gab als heute. Brian Jenkins amerikanische Bürger an islamistischen den können, einer wissenschaftlichen kommt für diesen Zeitraum auf 60 bis Terroranschlägen beteiligt sind. Des Analyse nicht stand. Deshalb soll in die- 70 Terroraktionen in den USA pro Jahr, Weiteren werden die Beziehungen zwi- sem Artikel das Problem des „Home- wobei es sich in den meisten Fällen um schen transnationalen Terrornetzwerken grown Terrorism“ noch einmal in vier Bombenanschläge handelte.3 -

Rational Classification in the War on Terrorism

LCB_11_4_ART3_LCB_11_4_ART3_YIN.DOC.DOC 12/12/2007 3:04:00 PM ENEMIES OF THE STATE: RATIONAL CLASSIFICATION IN THE WAR ON TERRORISM by Tung Yin* In this Article, Professor Yin proposes a new solution to the classification of suspected terrorists in the War on Terrorism—that national identity should be the determining factor in deciding whether combatants are criminally prosecuted or detained by the military. Currently, the Bush Administration does not seem to be following any discernible rubric in classifying enemy combatants. Professor Yin proves this point by examining disparate classifications arrived at by the Executive Branch since the War on Terrorism began. He argues against such modalities of classification as citizenship, geography, and utility because they produce both unreasonable and unsatisfactory results. Finally, Professor Yin lays out guidelines by which his national identity solution can be practically implemented, arguing that the Executive Branch can most effectually institute his proposal. I. ENEMIES OF THE STATE.................................................................. 906 A. Similar Circumstances, Different Treatment?..................................... 907 B. Classifying a Person as a Criminal Defendant or as an Enemy Combatant ............................................................................ 910 1. Criminal Prosecution ................................................................. 911 2. Military Detention...................................................................... 913 II. LOOKING -

Radikalisierung Und Terrorismus Im Westen

ISSN 0007–3121 DER BÜRGER IM STAAT 4–2011 Radikalisierung und Terrorismus im Westen BiS_2011_04_Ums.indd U:1 11.01.12 11:51 DER BÜRGER IM STAAT INHALT Andreas Hasenclever und Jan Sändig Religion und Radikalisierung? Zu den säkularen Mechanismen der Rekrutierung transnationaler Terroristen im Westen 204 Karl Cordell „Homegrown Terrorismus“ oder transnationaler Terrorismus? Ein Beitrag zur Debatte 214 Clark McCauley/Sophia Moskalenko Mechanismen der Radikalisierung von Individuen und Gruppen 219 HEFT 4–2011 Anja Dalgaard-Nielsen 61. JAHRGANG Terrorismusprävention und Deradikalisierung: ISSN 0007–3121 ein dänisches Präventionsprogramm 225 Guido Steinberg „Der Bürger im Staat” wird von der Landeszentrale Die neuen Internationalisten – Organisationsformen für politische Bildung Baden-Württemberg herausgegeben. des islamistischen Terrorismus 228 DIREKTOR DER LANDESZENTRALE Jean-Luc Marret Lothar Frick Dschihadismus „Made in France“ und Terrorismusbekämpfung 235 REDAKTION William Hammonds Siegfried Frech, [email protected] Das Prevent-Programm zur Verhinderung gewaltsamer REDAKTIONSASSISTENZ Radikalisierung in Großbritannien 241 Barbara Bollinger, [email protected] Edwin Bakker ANSCHRIFT DER REDAKTION Dschihadistischer „Homegrown Terrorismus“ Staffl enbergstraße 38, 70184 Stuttgart in den Niederlanden 246 Telefon 0711/164099-44, Fax 0711/164099-77 Anthony Celso HERSTELLUNG Schwabenverlag Media der Schwabenverlag AG Der Mythos des „homegrown terrorism“ in Spanien 252 Senefelderstraße 12, 73760 Ostfi ldern-Ruit Martin Balluch Telefon 0711/4406-0, Fax 0711/442349 Radikal, aber nicht terroristisch: Die Tier- und Umweltschutz- GESTALTUNG TITEL bewegung in Österreich 258 Bertron.Schwarz.Frey, Gruppe für Gestaltung, Ulm Rezensionen 264 GESTALTUNG INNENTEIL Britta Kömen, Schwabenverlag Media der Schwabenverlag AG VERTRIEB Verlagsgesellschaft W.E. Weinmann mbH Postfach 1207, 70773 Filderstadt Telefon 0711/7001530, Fax 0711/70015310 Der Bürger im Staat erscheint vierteljährlich. -

Congressional Research Service

Order No. EBTER125 July 1, 2004 Congressional Research Service Terrorism : Federal Crimes Implicated Charles Doyle Issue Definition Current Law Convictions and Current_ Charges Terrorist Cells Providing Financial Support Enemy Combatants GuantanamoCharges Assistance to Countries Supporting Terrorism Issue Definition The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, implicated a number of federal criminal laws . Although the hijackers themselves died in the attacks, federal prosecutors have filed charges in several terrorist-related cases . Zacarias Moussaoui is being prosecuted as a co-conspirator of the hijackers . Three other men, alleged to have helped them secure false identification, have entered plea bargains. In terrorist cases not directly linked to the September 11 attacks, Richard Reid, has been sentenced to life imprisonment for trying to destroy an international flight using explosives concealed in his shoes . John Walker Lindh, the so-called American Taliban, pled guilty to lesser charges after being indicted for conspiring to murder an American overseas and for providing material support to Al Qaeda and the Taliban . Two others, American Jose Padilla and Qatari Ali Saleh Kahlah Al-Marri, initially accused of criminal offenses have been declared enemy combatants and turned over to military authorities . Two nationals of Yemen have been indicted, but remain at large, for the attacks on the USS Cole and the USS The Sullivans in Aden, Yeman . Civilian and military authorities have also brought charges involving the mishandling of classified information relating to the incarceration of enemy combatants in Guantanamo, Cuba . Elsewhere, an attorney for the Sheikh Abdel Rahman convicted of sedition for earlier acts of terrorism, has been accused of a series of crimes relating to Rahman's continued involvement with terrorist activities . -

Report from the Field: the Usa Patriot Act at Work

U.S. Department of Justice REPORT FROM THE FIELD: THE USA PATRIOT ACT AT WORK JULY 2004 Table of Contents I. Introduction........................................................................................................................1 II. Enhancing the Federal Government’s Capacity to Share Intelligence .........................2 III. Strengthening the Criminal Laws Against Terrorism ..................................................9 IV. Removing Obstacles to Investigating Terrorism..........................................................15 V. Updating the Law to Reflect New Technology ..............................................................18 VI. Conclusion ........................................................................................................................28 I. Introduction Immediately after the brutal terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, both Congress and the Administration reexamined the legal tools available to investigators and prosecutors in the fight against terrorism. Taking into account the lessons learned from past experience, they found these tools to be inadequate. Acting swiftly and responsibly to correct numerous deficiencies, Congress and the Administration set out to update, strengthen, and expand laws governing the investigation and prosecution of terrorism within the parameters of the Constitution and our national commitment to the protection of civil rights and civil liberties. As a result of those efforts, Congress overwhelmingly passed, and on October 26, 2001, the President -

American Jihadist Terrorism: Combating a Complex Threat

American Jihadist Terrorism: Combating a Complex Threat Jerome P. Bjelopera Specialist in Organized Crime and Terrorism January 23, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R41416 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress American Jihadist Terrorism: Combating a Complex Threat Summary This report describes homegrown violent jihadists and the plots and attacks that have occurred since 9/11. For this report, “homegrown” describes terrorist activity or plots perpetrated within the United States or abroad by American citizens, legal permanent residents, or visitors radicalized largely within the United States. The term “jihadist” describes radicalized individuals using Islam as an ideological and/or religious justification for their belief in the establishment of a global caliphate, or jurisdiction governed by a Muslim civil and religious leader known as a caliph. The term “violent jihadist” characterizes jihadists who have made the jump to illegally supporting, plotting, or directly engaging in violent terrorist activity. The report also discusses the radicalization process and the forces driving violent extremist activity. It analyzes post-9/11 domestic jihadist terrorism and describes law enforcement and intelligence efforts to combat terrorism and the challenges associated with those efforts. Appendix A provides details about each of the post-9/11 homegrown jihadist terrorist plots and attacks. There is an “executive summary” at the beginning that summarizes the report’s findings. Congressional -

Estimating the Prevalence of Entrapment in Post-9/11 Terrorism Cases, 105 J

Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology Volume 105 | Issue 3 Article 2 Summer 2015 Estimating the Prevalence of Entrapment in Post-9/ 11 Terrorism Cases Jesse J. Norris Hanna Grol-Prokopczyk Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc Part of the Criminal Law Commons, and the Criminology Commons Recommended Citation Jesse J. Norris and Hanna Grol-Prokopczyk, Estimating the Prevalence of Entrapment in Post-9/11 Terrorism Cases, 105 J. Crim. L. & Criminology (2015). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/jclc/vol105/iss3/2 This Criminal Law is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology by an authorized editor of Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. 2. NORRIS FINAL FOR PRINTER (CORRECTED OCT. 11) 10/11/2016 9:14 AM 0091-4169/15/10503-0609 THE JOURNAL OF CRIMINAL LAW & CRIMINOLOGY Vol. 105, No. 3 Copyright © 2016 by Jesse J. Norris and Hanna Grol-Prokopczyk Printed in U.S.A. ESTIMATING THE PREVALENCE OF ENTRAPMENT IN POST-9/11 TERRORISM CASES JESSE J. NORRIS* & HANNA GROL-PROKOPCZYK** [T]he essence of what occurred here is that a government . came upon a man both bigoted and suggestible, one who was incapable of committing an act of terrorism on his own, created acts of terrorism out of his fantasies of bravado and bigotry, and made those fantasies come true. [R]eal terrorists would not have bothered themselves with a person who was so utterly inept.