Obstructed Labor As an Underlying Cause of Maternal Mortalit Ted Labor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download/Pdf/132634899.Pdf

THE END OF CATTLE’S PARADISE HOW LAND DIVERSION FOR RANCHES ERODED FOOD SECURITY IN THE GAMBOS, ANGOLA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 9 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2019 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Girl leading a pair of oxen pulling a traditional cart in the Gambos, (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Angola © Amnesty International https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2019 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: AFR 12/1020/2019 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS GLOSSARY 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 7 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 METHODOLOGY 14 THE GAMBOS 16 FOOD INSECURITY IN THE GAMBOS 19 DECLINING MILK PRODUCTION 19 DECLINING FOOD PRODUCTION 23 HUNGER AND MALNUTRITION 24 THE ROOT OF THE PROBLEM 26 LAND DISPOSSESSION AND FOOD SECURITY 27 CATTLE ARE OUR LIFE 29 THE SPECIAL STATUS OF TUNDA AND CHIMBOLELA 31 ECONOMIC VALUES OF CATTLE 32 “THE CATTLE ARE OUR BANK, INSURANCE AND SOCIAL SECURITY” 32 “THE CATTLE GIVE US EDUCATION” 33 “THE CATTLE ARE OUR TRACTORS” 34 FAILURE TO PREVENT LAND DISPOSSESSION 37 EVIDENCE FROM SATELLITE 38 EVIDENCE FROM THE GOVERNMENT 38 EVIDENCE FROM THE PASTORALISTS 40 1. -

Quipungo Na Liderança Da Produção De Milho

Terça, 20 de Junho 2017 15:38 Director: José Ribeiro Director Adjunto: Victor de Carvalho REPORTAGEM Quipungo na liderança da produção de milho Arão Martins | Quipungo 19 de Junho, 2017 O potencial do município do Quipungo, Huíla, na produção e colheita de cereais, faz da região o destino de negociantes, empresários e pessoas singulares na compra do milho, massango e massambala. (/fotos? album=230522) Centenas de toneladas de milho produzidas anualmente no município de Quipungo Fotografia: Arão Martins | Edições Novembro | Huíla Quipungo é um dos 14 municípios da província da Huíla, situa-se a 120 quilómetros a Leste da cidade do Lubango e tem uma extensão territorial calculada em 5.675 quilómetros quadrados e está confinado a Norte com os municípios de Caluquembe, Cacula e Chicomba. A Este com a Matala, a Sul com os Gambos e a Oeste com os municípios do Lubango, Cacula e Chibia. O nome Quipungo, reza a história, veio do vocábulo de origem nhaneka-humbi, (Epungo), que significa grão de milho, e esse elemento foi encontrado num elefante abatido por um caçador de nome Galle Cumena, oriundo da etnia Mungabwe, cujo clã totémico pertence aos Mukwanhama e, que na altura, na sua actividade apaixonante, atingiu as margens do rio Hilinguty, onde fixou sua residência oficial, na zona de Mãe-Mãe, actual Ombala de Yotyipungu. Vieira Muanda é um pequeno empresário famoso, que instalou na localidade de Malipi, (12 quilómetros da sede municipal de Quipungo), um centro de compra de milho denominado “Potchoto Tchepungu”, que traduzido em português significa centro de milho. O centro serve de compra de milho produzido pelos camponeses nas localidades de Tchindumbili, Kavissamba, Nombindji, Tchivava 1 e 2, Matemba, Cavilevi, dentre outras localidades, para ser vendido nas províncias do Huambo, Benguela, Bié, Cuanza Sul e Luanda. -

Evaluation of Norweegian Refugee Councils Distribution and Food Security Programmes - Southern Angola 1997-2007

T R O P E R E T E L P M O C NORWEGIAN REFUGEE COUNCIL EVALUATION REPORT EVALUATION OF NORWEEGIAN REFUGEE COUNCILS DISTRIBUTION AND FOOD SECURITY PROGRAMMES - SOUTHERN ANGOLA 1997-2007 DISTRIBUTION AND FOOD SECURITY PROGRAMME IN ANGOLA BY CHRISTIAN LARSSEN JUNE 2008 Evaluation of Norwegian Refugee Council Distribution Programmes – Southern Angola, 1999-2007 FINAL REPORT 12 March 2008 Evaluator Christian Larssen Evaluation of NRC Distribution Programme – Angola Page 1 of 53 Content Executive Summary 3 Map of Angola 5 1. Project Description and Summary of Activities 6 2. Evaluation of project impact, effectiveness and efficiency 20 3. Evaluation of project sustainability 27 4. Conclusions, Lessons Learned and Recommendations 31 5. Evaluation purpose, scope and methodology 35 Annexes: A. Distribution Tables, NRC-Angola 2002-2007 B. Evaluation team and Programme C. Terms of Reference D. List of meetings/people contacted E. List of documents used F. Glossary and Abbreviations G. UN OCHA Access Map for Angola 2002 and 2003 The observations, conclusions and recommendations contained in this report are the exclusive responsibility of the evaluator/consultant, meaning that they do not necessarily reflect the views of the Norwegian Refugee Council or its staff Evaluation of NRC Distribution Programme – Angola Page 2 of 53 Executive Summary 1. Project Description and Summary of Project Activities Towards the end of the 1990’s, when the people had to flee their villages for Matala, through the emergency phase in the reception centres, NRC in collaboration with WFP and FAO provided necessary food-aid and essential distribution of non-food items. The IDPs also received support for subsistence farming and reconstruction of schools and health-post, providing education and basic health care in the centres. -

ANGOLA FOOD SECURITY UPDATE July 2003

ANGOLA FOOD SECURITY UPDATE July 2003 Highlights The food security situation continues to improve in parts of the country, with the overall number of people estimated to need food assistance reduced by four percent in July 2003 relieving pressure on the food aid pipeline. The price of the least-expensive food basket also continues to decline after the main harvest, reflecting an improvement in access to food. According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the results of both the latest nutritional surveys as well as the trend analysis on admissions and readmissions to nutritional rehabilitation programs indicate a clear improvement in the nutritional situation of people in the provinces considered at risk (Benguela, Bie, Kuando Kubango). However, the situation in Huambo and Huila Provinces still warrants some concern. Household food stocks are beginning to run out just two months after the main harvest in the Planalto area, especially for the displaced and returnee populations. In response to the current food crisis, relief agencies in Angola have intensified their relief efforts in food insecure areas, particularly in the Planalto. More than 37,000 returnees have been registered for food assistance in Huambo, Benguela, Huila and Kuando Kubango. The current food aid pipeline looks good. Cereal availability has improved following recent donor contributions of maize. Cereal and pulse projections indicate that total requirements will be covered until the end of October 2003. Since the planned number of beneficiaries for June and July 2003 decreased by four percent, it is estimated that the overall availability of commodities will cover local food needs until end of November 2003. -

Executive Summaries

400 kV Transmission Line Belém do Huambo Substation to Lubango Substation (Angola) EXECUTIVE SUMMARIES ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) & RESETTLEMENT ACTION PLAN (RAP) 400 kV Transmission Line Belém do Huambo Substation to Lubango Substation (Angola) ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT (ESIA) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. INTRODUCTION Angola is a country blessed with an abundance of natural resources, particularly as it relates to the energy sector and power sub-sector. The power system was developed over time with the main source being hydropower and this will continue to be the main source of electrical energy in the future supplemented with gas, wind and solar. At present the major generations totalize 4,3 GW, being 55% generated by hydropower plants. One of the goals of the Angola’s National Development Plan is to increase the access to electricity from 36% in 2017 to 50% in 2022. On the other hand, the National Strategy for Climate Change (2018-2030) calls for the transition to a low carbon economy and aims to electrify 60% of the rural population by 2025 and increase access to low-carbon energy in rural areas. The Cuanza River Basin (in the north region) was identified as a key area for development of hydropower generation projects to support Angola’s growth development, with potential to achieve a total of 7000 MW of installed capacity. Two hydropower plants are already located in Cuanza River: Cambambe (960 MW) and Capanda (520 MW) and two others are under construction Laúca (2067 MW) and Caculo Cabaça (2051 MW), with Laúca already generating some power. -

Chapter 15 the Mammals of Angola

Chapter 15 The Mammals of Angola Pedro Beja, Pedro Vaz Pinto, Luís Veríssimo, Elena Bersacola, Ezequiel Fabiano, Jorge M. Palmeirim, Ara Monadjem, Pedro Monterroso, Magdalena S. Svensson, and Peter John Taylor Abstract Scientific investigations on the mammals of Angola started over 150 years ago, but information remains scarce and scattered, with only one recent published account. Here we provide a synthesis of the mammals of Angola based on a thorough survey of primary and grey literature, as well as recent unpublished records. We present a short history of mammal research, and provide brief information on each species known to occur in the country. Particular attention is given to endemic and near endemic species. We also provide a zoogeographic outline and information on the conservation of Angolan mammals. We found confirmed records for 291 native species, most of which from the orders Rodentia (85), Chiroptera (73), Carnivora (39), and Cetartiodactyla (33). There is a large number of endemic and near endemic species, most of which are rodents or bats. The large diversity of species is favoured by the wide P. Beja (*) CIBIO-InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Vairão, Portugal CEABN-InBio, Centro de Ecologia Aplicada “Professor Baeta Neves”, Instituto Superior de Agronomia, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] P. Vaz Pinto Fundação Kissama, Luanda, Angola CIBIO-InBIO, Centro de Investigação em Biodiversidade e Recursos Genéticos, Universidade do Porto, Campus de Vairão, Vairão, Portugal e-mail: [email protected] L. Veríssimo Fundação Kissama, Luanda, Angola e-mail: [email protected] E. -

Undp Gef Apr/Pir 2006

FAO-GEF Project Implementation Review 2019 – Revised Template Period covered: 1 July 2018 to 30 June 2019 1. Basic Project Data General Information Region: Africa Country (ies): Angola Project Title: Integrating climate resilience into agricultural and agropastoral production systems through soil fertility management in key productive and vulnerable areas using the Farmer Field School approach (IRCEA) FAO Project Symbol: GCP/ANG/050/LDF GEF ID: 5432 GEF Focal Area(s): Climate Change Adaptation (CCA) Project Executing Partners: Ministry of Environment (MINAMB ), Ministry of Agriculture and Forest (MINAGRIF) Project Duration: Milestone Dates: Datas GEF CEO Endorsement Date 05/05/2016 Project Implementation Start 03/11/2016 Date/EOD: Proposed Project 30/09/2021 Implementation End Date/NTE1: Revised project implementation N/A end date (if applicable) 2 Actual Implementation End N/A Date3: Funding GEF Grant Amount (USD) 6,668,182 Total Co-financing amount as 23,619,230 included in GEF CEO Endorsement Request/ProDoc4 1 as per FPMIS 2 In case of a project extension. 3 Actual date at which project implementation ends/closes operationally -- only for projects that have ended. Page 1 of 27 Total GEF grant disbursement as 2,683,757 of June 30, 2019 (USD m): Total estimated co-financing 11,900,000 materialized as of June 30, 20195 Review and Evaluation Date of Most Recent Project Dez 2018 Steering Committee: Mid-term Review or Evaluation 01/10/2019 Date planned (if applicable): Mid-term review/evaluation 01/10/2019 actual: Mid-term review or evaluation YES due in coming fiscal year (July 2019 – June 2020). -

March 3 1,2006

CLUSA - ANGOLA RURAL GROUP ENTERPRISES AND AGRICULTURAL MARKETING IN ANGOLA (RGEIAMOA) Find Report November ZOO1 - December 2005 Submitted to the United States Agency for International Development Cooperative Agreement 654-00-00065-00 March 3 1,2006 CLUSA - Cooperative League ofthe United Staies of America NCBA - National Coojwratiw Business Association CLUS.4 Angola final repon of RGUAMOA USAIDfwded Pmgram (2001 .2005) Table of Contents I . Executive Summary .....................................................3 I1 . Context in which the RGEJAMOA was implemented ............5 111 . Goals, Purpose and Objectives........................................ 6 IV . Funding .................................................................. .., 7 v . Intervention Areas and Number of Clients Assisted ............-8 VI . Intervention strategies and Approach ...............................11 VII . Program Achievements................................................. 11 VIII . Constraints.. .............................................................. 17 IX . Lessons Learned ......................................................... 17 I. Executive Summary This final report documents relevant aspects of the implementation of the USAID-funded Rural Group Enterprises and Agricultural Marketing (RGWAMOA) by the Cooperative League of the USA (CLUSA) doing business in the USA as the National Cooperative Business Association (NCBA). The program started officially on October 3 1, 2005, and ended on December 15, 2005. It summarizes achievements of the program, -

Chicomba Fomenta a Construção De Casas Sociais Jornal De Angola 11

Chicomba fomenta a Nas casas que estão prestes a ficar construção de casas sociais concluídas, "os professores vão Jornal de Angola poder acomodar-se em grupos com- posto por cinco ou seis pessoas", 11 de Agosto de 2012 afirmou, confiando que, deste modo, a falta de habitações para os téc- A construção das moradias, no nicos provenientes de vários pontos âmbito do Programa Nacional de fique resolvida. Urbanismo e Habitação do "Nos próximos cinco anos, Executivo, já mereceu o Chicomba deve construir 3.500 reconhecimento das autoridades casas para ser considerada cidade locais e dos munícipes por ajudar a e os jovens devem apostar cada vez atrair quadros quali-ficados e, desse mais nisso", sublinhou Isaac dos modo, contribuir para o Anjos.O Programa Municipal desenvolvimento do município. Integrado de Desenvolvimento Rural As casas, orçadas em 200 milhões e Combate à Pobreza facultou o de kwanzas, estão projectadas para bem-estar a mais de 85 mil uma área superior a 90 mil metros habitantes das localidades do Quê, quadrados, estando igualmente Cuenda, Libongue, Mbule e outras, previstos armamentos, espaços segundo a administradora municipal verdes e estruturas de sanea-mento de Chicomba, Lúcia Francisco. básico. Diversas obras O governador da Huíla, Isaac dos As diversas obras executadas Anjos, que verificou o andamento incidiram na construção de 12 das obras, considerou-o satisfatório escolas com seis salas cada, seis e realçou a qualidade das moradias. postos de saúde, cinco casas para "As obras das 40 casas decorreram os técnicos, parques infantis, a ritmo acelerado e estão quase campos polivalentes, sistemas de concluídas", garantiu. -

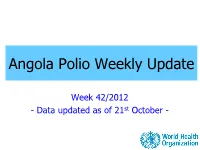

Weekly Polio Eradication Update

Angola Polio Weekly Update Week 42/2012 - Data updated as of 21st October - * Data up to Oct 21 Octtoup Data * Reported WPV cases by month of onset and SIAs, and SIAs, of onset WPV cases month by Reported st 2012 2008 13 12 - 11 2012* 10 9 8 7 WPV 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 Jul-08 Jul-09 Jul-10 Jul-11 Jul-12 Jan-08 Jun-08 Oct-08 Jan-09 Jun-09 Oct-09 Jan-10 Jun-10 Oct-10 Jan-11 Jun-11 Oct-11 Jan-12 Jun-12 Feb-08 Mar-08 Apr-08 Feb-09 Mar-09 Apr-09 Feb-10 Mar-10 Apr-10 Fev-11 Mar-11 Apr-11 Feb-12 Mar-12 Apr-12 Sep-08 Nov-08 Dec-08 Sep-09 Nov-09 Dec-09 Sep-10 Nov-10 Dez-10 Sep-11 Nov-11 Dec-11 Sep-12 May-08 Aug-08 May-09 Aug-09 May-10 Aug-10 May-11 Aug-11 May-12 Aug-12 Wild 1 Wild 3 mOPV1 mOPV3 tOPV Angola bOPV AFP Case Classification Status 22 Oct 2011 to 21 Oct 2012 290 Reported Cases 239 3 43 5 0 Discarded Not AFP Pending Compatible Wild Polio Classification 27 0 16 Pending Pending Pending final Lab Result ITD classification AFP Case Classification by Week of Onset 22 Oct 2011 to 21 Oct 2012 16 - 27 pending lab results - 16 pending final classification 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 43 44 45 46 48 49 50 51 52 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 Pending_Lab Pending_Final Class Positive Compatible Discarded Not_AFP National AFP Surveillance Performance Twelve Months Rolling-period, 2010-2012 22 Oct 2010 to 21 Oct 2011 22 Oct 2011 to 21 Oct 2012 NP AFP ADEQUACY NP AFP ADEQUACY PROVINCE SURV_INDEX PROVINCE SURV_INDEX RAT E RAT E RAT E RAT E BENGO 4.0 100 4.0 BENGO 3.0 75 2.3 BENGUELA 2.7 -

Governo Provincial Da Huíla Gabinete Provincial De Infra-Estruturas E Serviços Técnicos

REPÚBLICA DE ANGOLA GOVERNO PROVINCIAL DA HUÍLA GABINETE PROVINCIAL DE INFRA-ESTRUTURAS E SERVIÇOS TÉCNICOS 8º CONSELHO CONSULTIVO DO MINEA Síntese Sobre o sector de energia e águas Setembro, 2018 ÍNDICE 1. INTRODUÇÃO 2. CARACTERIZAÇÃO DO SUB-SECTOR ENERGIA 3. PRODUÇÃO, TRANSPORTE , DISTRIBUIÇÃO E TAXA DE COBERTURA DE ENERGIA 4. ILUMINAÇÃO PÚBLICA 5. PRINCIPAIS ACÇÕES REALIZADAS 6. PROJECTOS 7. CONSTRANGIMENTOS 8. PERSPECTIVAS 9. PARA MELHORAR O FUNCIONAMENTOS DE ENERGIA 10. CARACTERIZAÇÃO DO SUB-SECTOR DE ÁGUA 11. PRODUÇÃO, DISTRIBUIÇÃO DOS SISTEMAS DE ABASTECIMENTO DE ÁGUA E TAXA DE COBERTURA 12. INDICADORES DA BASE DE DADOS DA QUALIDADE DE ÁGUA NA PROVÍNCIA 13. PROJECTOS DO REFORÇO DO SISTEMAS DE ABASTECIMENTOS DE ÁGUA DAS SEDES MUNICIPAIS 14. PARA MELHORAR O FORNECIMENTO DE ÁGUA GABINETE DE INFRA –ESTRUTURAS E SERVIÇOS TÉCNICOS DO GOVERNO PROVINCIAL HUÍLA 1. INTRODUÇÃO Apesar das contingências da crise financeira que se verifica, o sector de energia e água, continua assistir realizações que visam o melhoramento gradual da disponibilidade dos serviços de energia e agua as populações; A disponibilização do combustível, para o sistemas de produção de energia e aguas aos municípios, esta a permitir a operacionalidade destes, e concomitantemente a disponibilidade e melhoria dos serviços; A vandalização dos sistemas de energia e aguas ao nível da Província, é cada vez mais acentuada e , muitos serviços que já estavam a contribuir na melhoria da qualidade de vida das populações deixaram de existir, destacando-se o roubo de contadores, placas solares , bombas submersivas , cabos de energia e outros ; A não implementação do Programa Agua Para Todos , está a criar um ambiente de estrema penalidade as populações e seus animais no meio rural, sugerindo-se que a sua reactivação seja um facto; GABINETE DE INFRA –ESTRUTURAS E SERVIÇOS TÉCNICOS DO GOVERNO PROVINCIAL HUÍLA 1 Sub-sector de energia 2. -

Biodiversity & Ecology

© University of Hamburg 2018 All rights reserved Klaus Hess Publishers Göttingen & Windhoek www.k-hess-verlag.de ISBN: 978-3-933117-95-3 (Germany), 978-99916-57-43-1 (Namibia) Language editing: Will Simonson (Cambridge), and Proofreading Pal Translation of abstracts to Portuguese: Ana Filipa Guerra Silva Gomes da Piedade Page desing & layout: Marit Arnold, Klaus A. Hess, Ria Henning-Lohmann Cover photographs: front: Thunderstorm approaching a village on the Angolan Central Plateau (Rasmus Revermann) back: Fire in the miombo woodlands, Zambia (David Parduhn) Cover Design: Ria Henning-Lohmann ISSN 1613-9801 Printed in Germany Suggestion for citations: Volume: Revermann, R., Krewenka, K.M., Schmiedel, U., Olwoch, J.M., Helmschrot, J. & Jürgens, N. (eds.) (2018) Climate change and adaptive land management in southern Africa – assessments, changes, challenges, and solutions. Biodiversity & Ecology, 6, Klaus Hess Publishers, Göttingen & Windhoek. Articles (example): Archer, E., Engelbrecht, F., Hänsler, A., Landman, W., Tadross, M. & Helmschrot, J. (2018) Seasonal prediction and regional climate projections for southern Africa. In: Climate change and adaptive land management in southern Africa – assessments, changes, challenges, and solutions (ed. by Revermann, R., Krewenka, K.M., Schmiedel, U., Olwoch, J.M., Helmschrot, J. & Jürgens, N.), pp. 14–21, Biodiversity & Ecology, 6, Klaus Hess Publishers, Göttingen & Windhoek. Corrections brought to our attention will be published at the following location: http://www.biodiversity-plants.de/biodivers_ecol/biodivers_ecol.php Biodiversity & Ecology Journal of the Division Biodiversity, Evolution and Ecology of Plants, Institute for Plant Science and Microbiology, University of Hamburg Volume 6: Climate change and adaptive land management in southern Africa Assessments, changes, challenges, and solutions Edited by Rasmus Revermann1, Kristin M.