Sabarimala and Women's Entry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COVID-19 Chapter Report – North India Chapter

____________________________________________ WMO NORTH INDIA CHAPTER ________________________________________________ ACTIVITY & PROGRESS REPORT (MARCH – APRIL 2020) – PANDEMIC REPORT BY MR.HAJI SHABBIR AHMED PATCA GENERAL SECRETARY, WMO NIC ACTIVITY & PROGRESS REPORT PANDEMIC PERIOD REPORT C O N T E N T S A. WMO North India Chapter Work Plan in COVID-19……………………… 2 B. WMO North India Chapter – Fight Against COVID-19 Pandemic…… 3-9 C. WMO North India Chapter – Relief work in holy month of Ramadan 10 D. WMO North India Chapter –Work Analysis Chart…………………………. 11 E. WMO North India Chapter – Meeting & Use of Modern Technology… 12 F. WMO North India Chapter –Thanks by President WMO NIC…………... 13 1 WMO NIC - Work Plan in COVID-19 In this unprecedented situation of Countrywide lockdown and various states governments’ restriction, it is challenging job for WMO NIC Team to help & reach out to needy people. And, therefore, before implementation of ration-distribution work, World Memon Organization North India Chapter had made a working plan for smooth execution of ration-kits distribution work in lockdown. WMO NORTH INDIA CHAPTER REGIONAL MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE (RMC) VARIOUS CITI CHAIRMENS OTHER ASSOCIATIONS YOUTH WING / VOLUNTEEERS’ NETWORK People We Served 2 WMO NIC - Fight Against COVID-19 Pandemic The outbreak of COVID-19, a novel corona virus identified in late 2019, was declared a public health emergency of international concern by WHO on 30 January. Corona viruses are a large family of viruses that cause illness ranging from the common cold to more severe respiratory diseases. Corona virus knows no borders. It is a global pandemic and our shared humanity demands a global response. -

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

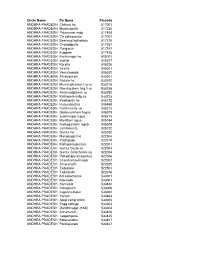

Post Offices

Circle Name Po Name Pincode ANDHRA PRADESH Chittoor ho 517001 ANDHRA PRADESH Madanapalle 517325 ANDHRA PRADESH Palamaner mdg 517408 ANDHRA PRADESH Ctr collectorate 517002 ANDHRA PRADESH Beerangi kothakota 517370 ANDHRA PRADESH Chowdepalle 517257 ANDHRA PRADESH Punganur 517247 ANDHRA PRADESH Kuppam 517425 ANDHRA PRADESH Karimnagar ho 505001 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagtial 505327 ANDHRA PRADESH Koratla 505326 ANDHRA PRADESH Sirsilla 505301 ANDHRA PRADESH Vemulawada 505302 ANDHRA PRADESH Amalapuram 533201 ANDHRA PRADESH Razole ho 533242 ANDHRA PRADESH Mummidivaram lsg so 533216 ANDHRA PRADESH Ravulapalem hsg ii so 533238 ANDHRA PRADESH Antarvedipalem so 533252 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta mdg so 533223 ANDHRA PRADESH Peddapalli ho 505172 ANDHRA PRADESH Huzurabad ho 505468 ANDHRA PRADESH Fertilizercity so 505210 ANDHRA PRADESH Godavarikhani hsgso 505209 ANDHRA PRADESH Jyothinagar lsgso 505215 ANDHRA PRADESH Manthani lsgso 505184 ANDHRA PRADESH Ramagundam lsgso 505208 ANDHRA PRADESH Jammikunta 505122 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur ho 522002 ANDHRA PRADESH Mangalagiri ho 522503 ANDHRA PRADESH Prathipadu 522019 ANDHRA PRADESH Kothapeta(guntur) 522001 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur bazar so 522003 ANDHRA PRADESH Guntur collectorate so 522004 ANDHRA PRADESH Pattabhipuram(guntur) 522006 ANDHRA PRADESH Chandramoulinagar 522007 ANDHRA PRADESH Amaravathi 522020 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadepalle 522501 ANDHRA PRADESH Tadikonda 522236 ANDHRA PRADESH Kd-collectorate 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Kakinada 533001 ANDHRA PRADESH Samalkot 533440 ANDHRA PRADESH Indrapalem 533006 ANDHRA PRADESH Jagannaickpur -

Pathanamthitta

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-A SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA 2 CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-A DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Village and Town Directory PATHANAMTHITTA Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala 3 MOTIF Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple A well known pilgrim centre of Kerala, Sabarimala lies in this district at a distance of 191 km. from Thiruvananthapuram and 210 km. away from Cochin. The holy shrine dedicated to Lord Ayyappa is situated 914 metres above sea level amidst dense forests in the rugged terrains of the Western Ghats. Lord Ayyappa is looked upon as the guardian of mountains and there are several shrines dedicated to him all along the Western Ghats. The festivals here are the Mandala Pooja, Makara Vilakku (December/January) and Vishu Kani (April). The temple is also open for pooja on the first 5 days of every Malayalam month. The vehicles go only up to Pampa and the temple, which is situated 5 km away from Pampa, can be reached only by trekking. During the festival period there are frequent buses to this place from Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kottayam. 4 CONTENTS Pages 1. Foreword 7 2. Preface 9 3. Acknowledgements 11 4. History and scope of the District Census Handbook 13 5. Brief history of the district 15 6. Analytical Note 17 Village and Town Directory 105 Brief Note on Village and Town Directory 7. Section I - Village Directory (a) List of Villages merged in towns and outgrowths at 2011 Census (b) -

Bombay High Court

2007 Bombay High Court 2007 JANUARY FEBRUARY MARCH APRIL S 7142128 S 4111825S 4111825S 1 8 15 22 29 M 1 8152229 M 51219 26 M 51219 26 M 2 9 16 23 30 T 2 9162330 T 6132027 T 6132027 T 3101724 W 3 10 17 24 31 W 7142128 W 7142128W 4111825 T 4 11 18 25 T 1 8 15 22 T 1 8 15 22 29 T 5121926 F 5 12 19 26 F 2916 23 F 2 9 16 23 30 F 6 13 20 27 S 61320 27 S 31017 24 S 3 10 17 24 31 S 7 14 21 28 1. Sundays, Second & Fourth Saturdays and other Holidays are shown in red. MAY 2. The Summer Vacation of the Court will commence on Monday the 7th May, JUNE S 6132027 2007 and the Court will resume its sitting on Monday the 4th June, 2007. S 3101724 3. The court will remain closed on account of October Vacation from 5th M 7142128 November to 18th November, 2007. M 4111825 T 1 8 15 22 29 4. Christmas Vacation from 24th December, 2007 to 6th January, 2008. T 5121926 5. Id-uz-Zuha, Muharram, Milad-un-Nabi, Id-ul-Fitr and Id-uz-Zuha W 2 9 16 23 30 respectively are subject to change depending upon the visibility of the W 6132027 T 3 10 17 24 31 Moon. If the Government of India declares any change in these dates through T 7142128 TV/AIR/Newspaper, the same will be followed. F 4 11 18 25 6. -

The High Court at Bombay (Extension of Jurisdiction to Goa, Daman and Diu) Act, 1981 Act No

THE HIGH COURT AT BOMBAY (EXTENSION OF JURISDICTION TO GOA, DAMAN AND DIU) ACT, 1981 ACT NO. 26 OF 1981 [9th September, 1981.] An Act to provide for the extension of the jurisdiction of the High Court at Bombay to the Union territory of Goa, Daman and Diu, for the establishment of a permanent bench of that High Court at Panaji and for matters connected therewith. BE it enacted by Parliament in the Thirty-second Year of the Republic of India as follows:— 1. Short title and commencement.—(1) This Act may be called the High Court at Bombay (Extension of Jurisdiction to Goa, Daman and Diu) Act, 1981. (2) It shall come into force on such date1 as the Central Government may, by notification in the Official Gazette, appoint. 2. Definitions.—In this Act, unless the context otherwise requires,— (a) “appointed day” means the date on which this Act comes into force; (b) “Court of the Judicial Commissioner” means the Court of the Judicial Commissioner for Goa, Daman and Diu. 3. Extension of jurisdiction of Bombay High Court to Goa, Daman and Diu.—(1) On and from the appointed day, the jurisdiction of the High Court at Bombay shall extend to the Union territory of Goa, Daman and Diu. (2) On and from the appointed day, the Court of the Judicial Commissioner shall cease to function and is hereby abolished: Provided that nothing in this sub-section shall prejudice or affect the continued operation of any notice served, injunction issued, direction given or proceedings taken before the appointed day by the Court of the Judicial Commissioner, abolished by this sub-section, under the powers then conferred upon that Court. -

Mindscapes of Space, Power and Value in Mumbai

Island Studies Journal, Vol. 9, No. 2, 2014, pp. 277-292 The epistemology of a sea view: mindscapes of space, power and value in Mumbai Ramanathan Swaminathan Senior Fellow, Observer Research Foundation (ORF) Fellow, National Internet Exchange of India (NIXI) Contributing Editor, Governance Now [email protected] ABSTRACT: Mumbai is a collection of seven islands strung together by a historically layered process of reclamation, migration and resettlement. The built landscape reflects the unique geographical characteristics of Mumbai’s archipelagic nature. This paper first explores the material, non-material and epistemological contours of space in Mumbai. It establishes that the physical contouring of space through institutional, administrative and non-institutional mechanisms are architected by complex notions of distance from the city’s coasts. Second, the paper unravels the unique discursive strands of space, spatiality and territoriality of Mumbai. It builds the case that the city’s collective imaginary of value is foundationally linked to the archipelagic nature of the city. Third, the paper deconstructs the complex power dynamics how a sea view turns into a gaze: one that is at once a point of view as it is a factor that provides physical and mental form to space. In conclusion, the paper makes the case that the mindscapes of space, value and power in Mumbai have archipelagic material foundations. Keywords : archipelago, form, island, mindscape, Mumbai, power, space, value © 2014 – Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. Introduction: unearthing the archipelagic historiography of Mumbai A city can best be described as a collection of spaces. Not in any ontological sense or in a physically linear form, but in an ever-changing, ever-interacting mesh of spatialities and territorialities that display the relative social relations of power existing at that particular point in time (Holstein & Appadurai, 1989). -

In the High Court of Judicature at Bombay

IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT BOMBAY ORDINARY ORIGINAL CIVIL JURISDICTION \9 NOTICE OF MOTION(NO.S2J"OF 2018 IN WRIT PETITION NO. 1286 OF 2018 Mumbai Cricket Association. ... Applicant (Original Respondent No.1) In the matter between NadimMemon ... Petitioner VERSUS Mumbai Cricket Association &Ors ... Respondents. INDEX Date Exh.No. Particulars Page No. Proforma Notice of Motion 1-8 Affidavit in support of Notice of . 9-15 Motion ". , 6/4/2018. A. Copy of order. 16-2~ 2/5/2018 B. News paper report in Times ofIndia 23 2/5/2018 C. Copy of Minutes of Committee of 24 Administrators of Respondent No.1 ~ IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT BOMBAY ORDINARY ORIGINAL CIVIL JURISDICTION NOTICE OF MOTION NO. OF 2018 IN WRIT PETITION NO. 1286 OF 2018 Mumbai Cricket Association, a public ) Trust registered under the provisions of ) Bombay public trust Act, 1950 as also a ) Society registered under the provision of the ) Societies Registration Act, 1860 having its ) Office at Cricket Center, Wankhede Stadium, ) Churchgate Mumbai- 400020. ) .. '" Applicant (Original Respondent No.1) In the matter between:- Nadim Memon, an adult Indian Inhabitant ) Occupation ;- Business having his address at ) 22, Rustom Sidwa Marg, Fort, Mumbai - 400 001 ) ... Petitioner Vis 1) Mumbai Cricket Association, a public ) Trust registered under the provisions of ) Bombay public trust Act, 1950 as also a ) Society registered under the provision of the ) Societies Registration Act, 1860 having its ) Office at Cricket Center, Wankhede Stadium, ) Churchgate Mumbai- 400020. ) v 2) Wizcraft International Entertainment Pvt. Ltd. ) A company registered under the Companies Act, 1956 ) Having its registered office at Satyadev Plaza, ) 5th Floor, Fun Republic Lane, Off. -

District Census Handbook, Greater Bombay

CENSUS OF INDIA, 1981 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK GREATER BOMBAY Compiled by THE MAHARASHTRA CENSUS DIRECTORATE BOMBAY 1'1l00'ED IN INDIA. BY THE MANAGER, YERAVDA PRISON PllESS, pum AND pmLlSHED mY THE DIRECTOR, GOVERNlrfENT PRINTING AND STATIONEK.Y, :t4AHAIASHTltA STATE, BOMBAY 400 004, 1986 [ Price ; Rs. 30.00 ] MAHARASHTRA <slOISTRICT GREATER BOMBAY ..,..-i' 'r l;1 KM" LJIo_'=:::I0__ ";~<====:io4 ___~ KNS . / \ z i J I i I ! ~ .............. .~ • .--p;_.. _ • K¢'J· '- \ o BUTCHER ..~ ISLANO '.. , * o' J o Boundary ('i5lrict ,-.-._. __ .- ,,' / ,~. Nat:onal iiighway ",- /" State Highw«y ... SH i Railwuy line with station. Broad Gauge j Riwr and Stream ~ w. ter lea I urIs ~;::m I Degr.e College and lech.kat Institution Res! Hcu~e. Circwit Hou~. ( P. W. D.l RH. CH Poot and Jel.graph office PlO ~~';; ® Based "pon Surv~! af IIIifia mat> wlth 1M 1J@rm~ion. of l~" SUfVI!YlII' G~QI rJ! Ifda. Tile territorial waters 01 Indio ~d into Ihe sea to a dOslonce of twet.... n(llltic:ol milos meGsIlt'ell hllm tn& "PlllVp..-Qle ~G5e lin~. ~ MOTIF V. T. Station is a gateway to the 'Mumbai' where thousands of people come every day from different parts of India. Poor, rich, artist, industrialist. toumt alike 'Mumbainagari' is welcoming them since years by-gone. Once upon a time it was the mai,n centre for India's independence struggle. Today, it is recognised as the capital of India for industries and trade in view of its mammoth industrial complex and innumerable monetary transactions. It is. also a big centre of sports and culture. -

Reportable in the High Court of Judicature at Bombay

WWW.LIVELAW.IN Board of Control for Cricket in India vs Deccan Chronicle Holding Ltd CARBPL-4466-20-J.docx GP A/W AGK & SSM REPORTABLE IN THE HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT BOMBAY ORDINARY ORIGINAL CIVIL JURISDICTION IN ITS COMMERCIAL DIVISION COMM ARBITRATION PETITION (L) NO. 4466 OF 2020 Board of Control for Cricket in India, a society registered under the Tamil Nadu Societies Registration Act 1975 and having its head office at Cricket Centre, Wankhede Stadium, Mumbai 400 020 … Petitioner ~ versus ~ Deccan Chronicle Holdings Ltd, a company incorporated under the Companies Act 1956 and having its registered office at 36, Sarojini Devi Road, Secunderabad, Andhra Pradesh … Respondent appearances Mr Tushar Mehta, Solicitor General, with FOR THE PETITIONER Samrat Sen, Kanu Agrawal, Indranil “BCCI” Deshmukh, Adarsh Saxena, Ms R Shah and Kartik Prasad, Advocates i/b Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas Page 1 of 176 16th June 2021 ::: Uploaded on - 16/06/2021 ::: Downloaded on - 16/06/2021 17:38:08 ::: WWW.LIVELAW.IN Board of Control for Cricket in India vs Deccan Chronicle Holding Ltd CARBPL-4466-20-J.docx Mr Haresh Jagtiani, Senior Advocate, with Mr Navroz Seervai, Senior Advocate, FOR THE RESPONDENT Mr Sharan Jagtiani, Senior Advocate, “DCHL” Yashpal Jain, Suprabh Jain, Ankit Pandey, Ms Rishika Harish & Ms Bhumika Chulani, Advocates i/b Yashpal Jain CORAM : GS Patel, J JUDGMENT RESERVED ON : 12th January 2021 JUDGMENT PRONOUNCED ON : 16th June 2021 JUDGMENT: OUTLINE OF CONTENTS This judgment is arranged in the following parts. A. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 4 B. THE CHALLENGE IN BRIEF; SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS................................................ 6 C. THE AMBIT OF SECTION 34 ................................................. -

Attukal Pongala Campaign Strategy

Attukal Pongala Campaign Strategy Attukal Pongala 2019 Attukal Pongala is a 10-day festival celebrated at the Attukal Temple, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India, during which there is a huge gathering of millions of women on the ninth day. This is the lighting of the Pongala hearth (called Pandarayaduppu) placed inside the temple by the chief priest. The festival is marked as the largest annual gathering of 2.5 million women by the Guinness World Records in 2009. This is the earliest Pongala festival in Kerala. This temple is also known by the name Sabarimala of women. Mostly Attukal Pongala falls in the month of March or April. Trivandrum Municipal Corporation successfully implemented green protocol for the third time with the help of the Health Department and Green Army International. The need of Green Pongala About 4 years back the amount of waste collected at the end of Attukal Pongala used to measure around 350 tons. Corporation took steps to spread messages of Green Protocol to the devotees and food distributers more effectively with the help of the Green Army. In 2016 Corporation brought this measure down to about 170 tons. Corporation continued to give out Green Protocol messages and warnings throughout the year. And the measure came down to 85 tons in 2017 and 75 tons in 2018. After the years of reduction in waste, Presently, this year, in 2019 the waste has reduced as much as 65 Tons. The numbers show the reason and need for Green Protocol implementation for festivals. It could be understood that festivals or huge gatherings of people anywhere can bring about a huge amount of wastes in which the mixing of food wastes and other materials makes handling of wastes difficult or literally impossible. -

District Census Handbook

Census of India 2011 KERALA PART XII-B SERIES-33 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS KERALA CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 KERALA SERIES-33 PART XII-B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PATHANAMTHITTA VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) Directorate of Census Operations, Kerala MOTIF Sabarimala Sree Dharma Sastha Temple A well known pilgrim centre of Kerala, Sabarimala lies in this district at a distance of 191 km. from Thiruvananthapuram and 210 km. away from Cochin. The holy shrine dedicated to Lord Ayyappa is situated 914 metres above sea level amidst dense forests in the rugged terrains of the Western Ghats. Lord Ayyappa is looked upon as the guardian of mountains and there are several shrines dedicated to him all along the Western Ghats. The festivals here are the Mandala Pooja, Makara Vilakku (December/January) and Vishu Kani (April). The temple is also open for pooja on the first 5 days of every Malayalam month. The vehicles go only up to Pampa and the temple, which is situated 5 km away from Pampa, can be reached only by trekking. During the festival period there are frequent buses to this place from Kochi, Thiruvananthapuram and Kottayam. Contents Pages 1 Foreword 1 2 Preface 3 3 Acknowledgement 5 4 History and Scope of the District Census Handbook 7 5 Brief History of the District 9 6 Administrative Setup 12 7 District Highlights - 2011 Census 14 8 Important Statistics 16 9 Section - I Primary Census Abstract (PCA) (i) Brief note on Primary Census Abstract 20 (ii) District Primary Census Abstract 25 Appendix to District Primary Census Abstract Total, Scheduled Castes and (iii) 33 Scheduled Tribes Population - Urban Block wise (iv) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Castes (SC) 41 (v) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Tribes (ST) 49 (vi) Sub-District Primary Census Abstract Village/Town wise 57 (vii) Urban PCA-Town wise Primary Census Abstract 89 Gram Panchayat Primary Census Abstract-C.D.