ENGL 1102 Writing About Literature Readings Compiled, Annotated, and Edited by Rhonda L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faulkner's Stylistic Difficulty: a Formal Analysis of Absalom, Absalom!

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English 12-14-2017 Faulkner's Stylistic Difficulty: Aormal F Analysis of Absalom, Absalom! Eric Sandarg Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Sandarg, Eric, "Faulkner's Stylistic Difficulty: Aormal F Analysis of Absalom, Absalom!." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2017. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/189 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FAULKNER’S STYLISTIC DIFFICULTY: A FORMAL ANALYSIS OF ABSALOM, ABSALOM! by ERIC SANDARG Under the Direction of Pearl McHaney, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The complex prose of Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom!, marked by lengthy sentences and confusing punctuation, resonates on both a rhetorical and an aesthetic level that earlier critics failed to recognize. INDEX WORDS: William Faulkner; Absalom, Absalom!; punctuation; syntax; diction; prose poetry; parentheses; sentences; repetition; Faulknerese. i ii FAULKNER’S STYLISTIC DIFFICULTY: A FORMAL ANALYSIS OF ABSALOM, ABSALOM! by ERIC SANDARG A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences Georgia State University 2017 iii Copyright by Eric Sandarg 2017 iv FAULKNER’S STYLISTIC DIFFICULTY: A FORMAL ANALYSIS OF ABSALOM, ABSALOM! by ERIC SANDARG Committee Chair: Pearl McHaney Committee: Malinda Snow Randy Malamud Electronic Version Approved: Office of Graduate Studies College of Arts and Sciences Georgia State University December 2017 v iv DEDICATION I invoked no muse for inspiration while composing this work; my two principal sources of motivation were decidedly sublunary but nonetheless helpful beyond description: Dr. -

Bomb Queen Volume 3: the Good, the Bad and the Lovely Pdf, Epub, Ebook

BOMB QUEEN VOLUME 3: THE GOOD, THE BAD AND THE LOVELY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jimmie Robinson | 126 pages | 05 Feb 2008 | Image Comics | 9781582408194 | English | Fullerton, United States Bomb Queen Volume 3: The Good, The Bad And The Lovely PDF Book Bomb Queen, in disguise, travels to Las Vegas in search of a weapon prototype at a gun convention and runs into Blacklight , also visiting Las Vegas for a comic convention. Related: bomb queen 1 bomb queen 1 cgc. More filters Krash Bastards 1. Superpatriot: War on Terror 3. Disable this feature for this session. The animal has mysterious origins; he appears to have some connections to the Mayans of South America. The Bomb Qu Sam Noir: Samurai Detective 3. Share on Facebook Share. Ashe is revealed to be a demon, and New Port City his sphere of influence. These are denoted by Roman numerals and subtitles instead of the more traditional sequential order. I had the worse service ever there upon my last visit. The restriction of the city limits kept Bomb Queen confined in her city of crime, but also present extreme danger if she were to ever leave - where the law is ready and waiting. This wiki. When the hero's efforts prove fruitless, the politician unleashes a chemically-created monster who threatens not only Bomb Queen but the city itself. The animal has mysterious origins and is connected to the Maya of Central America. Sometimes the best medicine is bitter and hard to swallow, and considering the current state of things, it seemed the perfect time for her to return to add to the chaos! Dragon flashback only. -

The Harvard Classics Eboxed

0113 DSIS Qil3D THE HARVARD CLASSICS The Five-Foot Shelf of Books THE HARVARD CLASSICS EDITED BY CHARLES W. ELIOT, LL.D. English Poetry IN THREE VOLUMES VOLUME II From Collins to Fitzgerald ^ith Introductions and l>iotes Yolume 41 P. F. Collier & Son Corporation NEW YORK Copyright, igro By p. F. Collier & Son uanufactuked in v. s. a. CONTENTS William Collins page FiDELE 475 Ode Written in mdccxlvi 476 The Passions 476 To Evening 479 George Sewell The Dying Man in His Garden 481 Alison Rutherford Cockburn The Flowers of the Forest 482 Jane Elliot Lament for Flodden 483 Christopher Smart A Song to David 484 Anonymous Willy Drowned in Yarrow 498 John Logan The Braes of Yarrow 500 Henry Fielding A Hunting Song 501 Charles Dibdin Tom Bowling 502 Samuel Johnson On the Death of Dr. Robert Levet 503 A Satire 504 Oliver Goldsmith When Lovely Woman Stoops 505 Retaliation 505 The Deserted Village 509 The Traveller; or, A Prospect of Society 520 Robert Graham of Gartmore If Doughty Deeds 531 Adam Austin For Lack of Gold 532 465 466 CONTENTS William Cowper page Loss OF THE Royal George 533 To A Young Lady 534 The Poplar Field 534 The Solitude of Alexander Selkirk 535 To Mary Unwin 536 To the Same 537 Boadicea: An Ode 539 The Castaway 54" The Shrubbery 54^ On the Receipt of My Mother's Picture Out of Norfolk 543 The Diverting History of John Gilpin 546 Richard Brinsley Sheridan Drinking Song 554 Anna Laetitia Barbauld Life 555 IsoBEL Pagan (?) Ca' the Yowes to the Knowes 556 Lady Anne Lindsay AuLD Robin Gray 557 Thomas Chatterton Song from ^lla 558 -

Download Article

International Conference on Humanities and Social Science (HSS 2016) Character Analysis of A Rose For Emily Wen-ge CHANG1 and Qian-qian CHE2 1Foreign Languages Department, Jilin Provincial Educational Institute, Changchun, Jilin, China E-mail: [email protected] 2Undergraduate student, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Troy, NY, America Keywords: Characterization, Symbol, Image. Abstract. William Faulkner is among the greatest experimentalists of the 20th century novelists. The 1950 Nobel Prize presentation speech calls Faulkner the “unrivaled master of all living British and American novelists”. A Rose for Emily is one of his best- known short stories and is widely used in English classroom. Some people regard the story as a reflection of the dying Old South and the growing New South, which is practical and bent on industrialization. Some read the story as an allegory. By the characterization of the heroine Miss Emily and with the use of symbols and images, we can understand the relationship between the South and the North, between the past and the present, illusion and reality, permanence and change, and death and life. Introduction William Faulkner (1897-1962) is a giant in the realm of American literature. More than simply a renowned Mississippi writer, the Nobel Prize-winning novelist and short story writer is acclaimed through the world as one of the twentieth century’s greatest writers. During what is generally considered his period of greatest artistic achievement, from The Sound and the Fury in 1929 to Go Down, Moses in 1942, Faulkner accomplished in a little over a decade more artistically than most writers accomplish over a lifetime of writing. -

The Mystery of the Louvre

~~'ORLU\\ mr I'CBLJEIILNU C ovr \\ i iq 'L:I~1~14 80 i)rill:r the hit-hnonn lio\c.ls uf Ll~e norld ~sitliin tile iach of the rnillioils, by prcsc.r,t~rl,o ilt ttt. lorre\.t powihlc pricc per copy, in cn,iT.l~!:aitsi~e, on ~..cfcllentpaper, with bc:wlii'[il ud duld~le birlrlinq, n long seric~lof storicr, .cl hi( :I el crylbody tins hc:~rd of :rnd could desire to re.d Nc.vrr Iwfnrc 1m It I~c~tlporsiiilc tu pllieni books of the v;orld's most, fnrriorls 11vir19 :r~~tl~orr at sr~clla bmnll price. To render it possible now it will be nert'w~ry th~tcnch rolrln~c should haye a sale of hundreds of thous:incls of copicr and that many volumes of tlic serics diotild in due course iind their wry into nearly ever-/ home, however Inmlble, in thc U~litedStuies and G,~nada. The publisher> hew %he utn~oslooniideim that thi8 c1~1will he achieved. Th(.novels of Wonm WIDE Pbnr I~HI\GCox- PANY will be selected by one of the movt dls. tingwslled of living mcn of letters, nntl II short biog~npl~icaland bibliogruphical notc on the author hnd bir works will I)(* nppc.ndrd lo cnch vulrlmr. THE LOUVR i,:ir~~-l-i)j;~\i~i~ojs1.5 visitcil f):,ris is f,~r~~i[i:irwith !lie Louvre. O~~t~vnrdlyit i:; a lo~ry;,l.?i:lgy, ::!.irn-looking builtling ni sombre grey s,tcmcJ.., that i'! o\irns~nenacin~lyoil to the rue de Rivoli. -

Champions Complete

Champions Complete Writing and Design Derek’s Special Thanks Derek Hiemforth To the gamers with whom I first discovered Champions and fell in love with the game: Doug Alger, Andy Broer, Indispensable Contributions Daniel Cole, Dan Connor, Dave Croyle, Guy Pilgrim, and Nelson Rodriguez. Without you guys, my college grades Champions 6th Edition: Aaron Allston and might have been better, but my life would have been much, Steven S. Long much worse. HERO System 6th Edition: Steven S. Long To Gary Denney, Robert Dorf, Chris Goodwin, James HERO System 4th Edition: George MacDonald, Jandebeur, Hugh Neilson, and John Taber, who generously offered insightful commentary and suggestions. Steve Peterson, and Rob Bell And, above all, to my beloved wife Lara, who loves her Original HERO System: George MacDonald and fuzzy hubby unconditionally despite his odd hobby, even Steve Peterson when writing leaves him sleepless or cranky. Layout and Graphic Design HERO System™®. is DOJ, Inc.’s trademark for its roleplaying Ruben Smith-Zempel system. HERO System Copyright © 1984, 1989, 2002, 2009, 2012 by DOJ, Development Inc. d/b/a Hero Games. All rights reserved. Champions, Dark Champions, and all associated characters Jason Walters © 1981-2009 by Cryptic Studios, Inc. All rights reserved. “Champions” and “Dark Champions” are trademarks of Cryptic Cover Art Studios, Inc. “Champions” and “Dark Champions” are used under license from Cryptic Studios, Inc. Sam R. Kennedy Fantasy Hero © 2003, 2010 by DOJ, Inc. d/b/a Hero Games. All rights reserved. Interior Art Star Hero © 2003, 2011 by DOJ, Inc. d/b/a Hero Games. All rights Peter Bergting, Storn Cook, Keith Curtis, reserved. -

A Rose for Emily”1

English Language & Literature Teaching, Vol. 17, No. 4 Winter 2011 Narrator as Collective ‘We’: The Narrative Structure of “A Rose for Emily”1 Ji-won Kim (Sejong University) Kim, Ji-won. (2011). Narrator as collective ‘we’: The narrative structure of “A Rose for Emily.” English Language & Literature Teaching, 17(4), 141-156. This study purposes to explore the narrative of fictional events complicated by a specific narrator, taking notice of his/her role as an internal focalizer as well as an external participant. In William Faulkner's "A Rose for Emily," the story of an eccentric spinster, Emily Grierson, is focalized and narrated by a townsperson, apparently an individual, but one who always speaks as 'we.' This tale-teller, as a first-hand witness of the events in the story, details the strange circumstances of Emily’s life and her odd relationships with her father, her lover, the community, and even the horrible secret hidden to the climactic moment at the end. The narrative 'we' has surely watched Emily for many years with a considerable interest but also with a respectful distance. Being left unidentified on purpose, this narrative agent, in spite of his/her vagueness, definitely knows more than others do and acts undoubtedly as a pivotal role in this tale of grotesque love. Seamlessly juxtaposing the present and the past, the collective ‘we’ suggests an important subject that the distinction between the past and the present is blurred out for Emily, for whom the indiscernibleness of time flow proves to be her hamartia. The focalizer-narrator describes Miss Emily in the same manner as he/she describes the South whose old ways have passed on by time. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

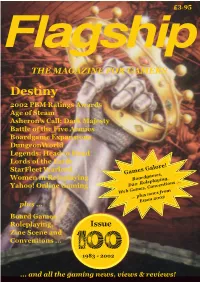

Flagship Issue

£3.95 Flagship THE MAGAZINE FOR GAMERS Destiny 2002 PBM Ratings Awards Age of Steam Asheron's Call: Dark Majesty Battle of the Five Armies Boardgame Expansions DungeonWorld Legends: Head to Head Lords of the Earth StarFleet Warlord Games Galore! Women in Roleplaying Boardgames, Yahoo! Online Gaming D20 Roleplaying, Web Games, Conventions ... ... plus news from plus ... Essen 2002 Board Games, Roleplaying, Issue Zine Scene and Conventions ... 100 1983 - 2002 ... and all the gaming news, views & reviews! AUSTERLITZ The Rise of the Eagle THE No 1 NAPOLEONIC WARGAME AUSTERLITZ is the premier PBM & PBEM Napoleonic Wargame. An award winner all over Europe, unparalleled realism and accurate modelling of Europe’s armies make this a Total Wargaming Experience! Main Features of the Game Two elegant battle systems Blockades, coastal defence and realistically simulating strategic fleet actions involving the period’s and tactical warfare. major naval powers. Large scale three map action Austerlitz offers you the chance to encompassing both European and play the wargame of your dreams! Colonial holdings. Command Napoleonic armies of over 100 battalions in the field. Try Active political and diplomatic your strategy across all the old system which encourages grand battlefields of Europe and fight alliance and evil treachery! battles that history never saw! Austerlitz is the ultimate challenge; Sophisticated trade and economic a thinking man’s dream of world systems give authentic control of a domination. Napoleonic economy. Austerlitz is now playable fully by email at a reduced price. For details or for a FREE Information Pack contact: SUPERSONIC GAMES LTD PO BOX 1812, Galston, KA4 8WA Email: [email protected] Phone: 01563 821022 or fax 01563 821006 (Mon-Fri 9am –5.30pm) Report from FLAGSHIP #100 the Bridge December/ January '02-'03 100 not out! IN THIS ISSUE .. -

Illuminating the Darkness: the Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel and Visual Art

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English English, Department of 8-2013 Illuminating the Darkness: The Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth-Century British Novel and Visual Art Cameron Dodworth University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Dodworth, Cameron, "Illuminating the Darkness: The Naturalistic Evolution of Gothicism in the Nineteenth- Century British Novel and Visual Art" (2013). Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English. 79. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/englishdiss/79 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Student Research: Department of English by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. ILLUMINATING THE DARKNESS: THE NATURALISTIC EVOLUTION OF GOTHICISM IN THE NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITISH NOVEL AND VISUAL ART by Cameron Dodworth A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: English (Nineteenth-Century Studies) Under the Supervision of Professor Laura M. White Lincoln, Nebraska August, 2013 ILLUMINATING THE DARKNESS: THE NATURALISTIC EVOLUTION OF GOTHICISM IN THE NINETEENTH- CENTURY BRITISH NOVEL AND VISUAL ART Cameron Dodworth, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2013 Adviser: Laura White The British Gothic novel reached a level of very high popularity in the literary market of the late 1700s and the first two decades of the 1800s, but after that point in time the popularity of these types of publications dipped significantly. -

ALL the PRETTY HORSES.Hwp

ALL THE PRETTY HORSES Cormac McCarthy Volume One The Border Trilogy Vintage International• Vintage Books A Division of Random House, Inc. • New York I THE CANDLEFLAME and the image of the candleflame caught in the pierglass twisted and righted when he entered the hall and again when he shut the door. He took off his hat and came slowly forward. The floorboards creaked under his boots. In his black suit he stood in the dark glass where the lilies leaned so palely from their waisted cutglass vase. Along the cold hallway behind him hung the portraits of forebears only dimly known to him all framed in glass and dimly lit above the narrow wainscotting. He looked down at the guttered candlestub. He pressed his thumbprint in the warm wax pooled on the oak veneer. Lastly he looked at the face so caved and drawn among the folds of funeral cloth, the yellowed moustache, the eyelids paper thin. That was not sleeping. That was not sleeping. It was dark outside and cold and no wind. In the distance a calf bawled. He stood with his hat in his hand. You never combed your hair that way in your life, he said. Inside the house there was no sound save the ticking of the mantel clock in the front room. He went out and shut the door. Dark and cold and no wind and a thin gray reef beginning along the eastern rim of the world. He walked out on the prairie and stood holding his hat like some supplicant to the darkness over them all and he stood there for a long time. -

Or Live Online Via Proxibid! Follow Us on Facebook and Twitter @Back2past for Updates

2/26 - Cooler Than Cool: Classic Comics & Toys 2/26/2020 This session will be held at 6PM, so join us in the showroom (35045 Plymouth Road, Livonia MI 48150) or live online via Proxibid! Follow us on Facebook and Twitter @back2past for updates. Visit our store website at GOBACKTOTHEPAST.COM or call 313-533-3130 for more information! (Showroom Terms: No buyer's premium!) Get the full catalog with photos, prebid and join us live at www.proxibid.com/backtothepast (See site for terms) LOT # LOT # 1 Auctioneer Announcements 12 Group of (5) Modern Notable Books Assortment may include semi-key issues, variants or 2 Tomb Raider #1 CGC 9.6/Key 1st Lara Croft in her own title. CGC graded comic. classic covers. Most are in VF/VF+ condition. You get all that is pictured. 3 Group of (5) Modern Notable Books Assortment may include semi-key issues, variants or 13 New Mutants #100/1991/1st X-Force classic covers. Most are in VF/VF+ condition. You get NM condition. all that is pictured. 14 Grimm Fairy Tales 2008 Annual/Pin-Up NM condition. 4 Batman Lost #1/2018/Dark Nights Metal NM condition. 15 Group of (5) Modern Notable Books Assortment may include semi-key issues, variants or 5 Dark Knights Rising #1/Dark Nights Metal NM condition. classic covers. Most are in VF/VF+ condition. You get all that is pictured. 5a Star Trek Autographed Action Figure Jadzia Dax figure, convention signed by actress Terry 15a Wizard of Oz 50th Anniversary Toy Lot Farrell. This does not come with a COA, but Back to Windups made in 1988.