Jose Gregorio Hernandez: a Chameleonic Presence in the Eye of the Medical Hurricane

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr. José Gregorio Hernández Para El Iniciador De La Medicina Experimental En Venezuela Progreso (1864-1919) De La Investigación Universitaria (APIU)

PROGRESO DE LA INVESTIGACION EL ARA UNIVERSITARIA ASOCIACION P NILO JIMÉNEZ PROGRESO DE LA INVESTIGACION EL TRIBUNAVolumen 15, números 1-2, 2014 ARA DEL INVESTIGADOR www.tribunadelinvestigador.com www.apiu.org.ve UNIVERSITARIA ASOCIACION P PROGRESO DE LA INVESTIGACION EL ARA UNIVERSITARIA ASOCIACION P www.apiu.org.ve Revista de la Asociación Dr. José Gregorio Hernández para el Iniciador de la Medicina Experimental en Venezuela Progreso (1864-1919) de la Investigación Universitaria (APIU) wwwwww.apiu.org.ve.apiu.org.ve ISSN: 1856-9080 Indizada en: LIVECS / LILACS / LATINEX / Saber UCV C O N T E N I D O Editorial / Sonia Hecker 1 Dr. José Gregorio Hernández Cisneros. Ilustre venezolano, estudiante, médico profesor e investigador de la Universidad Central de Venezuela / María Isabel Giacopini de Zambrano 2 CONSEJO DIRECTIVO Dr. José Gregorio Hernández: Pionero de la Medicina Experimental PERÍODO 2011-2014 CONSUELO RAMOS DE FRANCISCO Presidente (E) en Venezuela / Miguel Yáber Pérez 9 RAMÓN BENITO INFANTE Tesorero ELIZABETH MARCANO Secretaria de Actas y Correspondencia 29 de junio de 1919: Nace una devoción / María Isabel Giacopini de Zambrano 14 El Venerable Dr. José Gregorio Hernández, Técnico Histólogo por Excelencia, en el Año Jubilar de su Beatificación. Inicio de la Anatomía Patológica y Medicina Experimental en Venezuela / Dra. Claudia Antonieta Blandenier Bosson de Suárez 18 Relación entre Parámetros Antropométricos y la Respuesta Inmune frente al Sarampión en Niños Pre-escolares Venezolanos Vacunados / Natalia Pino, Benito Infante, María Teresa Zabala, Raimundo Cordero, Isabel Hagel 32 Estudio Nutricional del Pan de Yuca “Casabe” Elaborado por la Etnia Piaroa / Omar García, Ramón Benito Infante, Elizabeth Rivero, Carlos Rivera 40 REVISTA “TRIBUNA DEL INVESTIGADOR” Composición Corporal y el Patrón de Grasa en Niños y Niñas en Edad Escolar COMITÉ EDITORIAL de Zonas Rurales y Urbanas de Venezuela / Raimundo E. -

Cronicon OPEN ACCESS EC NEUROLOGY Case Report

Cronicon OPEN ACCESS EC NEUROLOGY Case Report Human Histoplasmosis in the Conus Medullaris: One Case from Anzoátegui-Venezuela Duvier Esteban Atay Gutiérrez1*, Luis Tracana1, Ricardo J Vallenilla1, Luis J González1, Lorenzo J Acevedo1, Antonio J Morocoima2, Leidi Herrera2 and Grace Socorro3 1Neurosurgery Service, University Hospital “Dr. Luis Razetti”, Barcelona, Anzoátegui State, Venezuela 2Department of Tropical Medicine, University of Oriente, Barcelona, Anzoátegui State, Venezuela 3Department of Pathology, Centro Médico Rivadeo, Lecherías, Anzoátegui State, Venezuela *Corresponding Author: Duvier Esteban Atay Gutiérrez, Neurosurgery Service, University Hospital “Dr. Luis Razetti”, Barcelona, Anzo- átegui State, Venezuela. Received: June 26, 2018 Abstract We report a case of histoplasmosis in the conus medullaris in a patient from Anzoátegui state, Venezuela. Neurohistoplasmosis is particularly rare in immunocompetent individuals, so progressive disseminated histoplasmosis in the central nervous system oc- curs in 5 - 10% of cases. The patient was male, 20 years old, immunocompetent, with a history of hunting and livestock activities. No history of respiratory disease. Current disease characterized by axial low back pain and isolated feverish episodes; the patient - dition worsened until his ability to walk or remain in a prolonged posture. Neuroimaging reported a single injury in the conus medul- self-medicated with standard non-steroidal anti-inflammatory and antipyretic drugs without satisfactory evolution. The patient con removal of the space-occupying granulomatous lesion and a biopsy was taken. Histological sections were stained with PAS, Grocott laris and marked eosinophilia in clinical paralleled evaluations. Due to increasing of neurological deficit, was performed the surgical and H-E and a bone marrow aspirate smear was stained with Giemsa. -

Villanueva and Anatomy of Concrete

Intervalolibre Villanueva and Anatomy of concrete Jorge Sánchez-Lander* - Mrs. Villanueva, when you want to ask something to the doctor, how does? -I do not ask him anything - I answered them-. Because whenever I ask him something he gives me three different solutions and I am worse than when I started. Do you know what they said? - How lucky you are! Only gives you three solutions! He gives us nearly seven! Margot en dos tiempos, retrato de una caraqueña del siglo XX, Adriana Villanueva, 2005. Born in the Consulate of Venezuela in London on May 30, 1900, Carlos Raúl Villanueva spends his early years in Europe. His academic training takes place at the Lycée Condorcet in Paris and later at the school of fine arts in the same city, where he graduated as an architect in 1928. A few months later he travelled to Venezuela to know the land which he has always considered its homeland and dedicated to his life and his work. For the beginning of the Decade of 1930, he was hired by the Ministry of public works, and within its first buildings stands the Hotel Jardín and the Maestranza of Maracay. In Caracas, it is the seat of the Museo de Bellas Artes and the Museo de Ciencias Naturales, great buildings that strengthen the desire for modernity in the capital city. After spending a few months in the school of urban planning at the University of Paris, he returned to Caracas and became part of the direction of urbanism of the Federal District in 1938, in which begins to develop a Monumental Plan of Caracas, led by the French engineer Maurice Rotival. -

Claudia Perez-Straziota, MD Page 1

Claudia Perez-Straziota, M.D. Page 1 CURRICULUM VITAE Claudia Perez-Straziota, M.D. Revised: April, 2017 NAME: Claudia E. Perez-Straziota, M.D. ADDRESS: 5550 Wilshire Blvd. Apt 334 TELEPHONE: (404) 229-6025 Los Angeles, CA 90036 E-MAIL: [email protected] CITIZENSHIP: Venezuelan and Italian VISA STATUS: Green Card. CURRENT POSITION AND AFFILIATIONS: CURRENT POSITION AND AFFILIATIONS: April 2017 – Present Staff Ophthalmologist Cornea Eye Institute 50 N La Cienaga Boulevard Suite 340 Beverly Hills, CA 90211 April 2017 – Present Clinical Assistant Professor University of Southern California + Los Angeles County Hospital 2051 Marengo Street Los Angeles, CA 90033 April 2017 – Present Post Doctoral Scientist Cedars Sinai Medical Center 8700 Beverly Blvd Los Angeles, CA 90048 PAST POSITIONS AND AFFILIATIONS: Oct. 2013 – Nov. 2016 Staff Ophthalmologist Forrest Eye Centers. 705 Jesse Jewell Pkwy Suite 100 Gainesville, GA 30501 Oct. 2013 – Nov. 2016 Staff Ophthalmologist Northeast Georgia Medical Center 743 Spring Street NE Gainesville, GA 30501 LICENSURES/BOARDS: 2008 Educational Commission of Foreign Medical Graduates 2011 Georgia State Medical License 2013 American Board of Ophthalmology Claudia Perez-Straziota, M.D. Page 2 2016 Medical Board of California EDUCATION: 1998-2004 Doctor of Medicine Universidad Central de Venezuela. Escuela Luis Razetti Caracas, Venezuela POSTGRADUATE TRAINING: 2008- 2009 Transitional Year Residency (Internship) Emory University School of Medicine Atlanta, GA 2009-2012 Residency in Ophthalmology Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Ophthalmology Atlanta, Georgia 2012-2013 Fellowship in Cornea, External Disease and Refractive Surgery Emory University School of Medicine, Department of Ophthalmology Atlanta, Georgia TRAINING EXPERIENCES 2004 Primary Care Outreach Internship San Carlos De Rio Negro Primary Care Center Amazonas, Venezuela 2004 Internship in Emergency Medicine. -

Rethinking the Instituto De Oncología Luis Razetti

Intervalolibre Rethinking the Instituto de Oncología Luis Razetti Jorge Sánchez Lander* "For many of us here, this has been our home, our dear old home." Jesús Felipe Parra. Graduation ceremony in IOLR, 1998. In 1936 the world was recovering from the devastation of World War I and, unknowing, would behoove between 1939 and 1945 suffer the most brutal armed conflict in history, World War II. On the other hand, science was overturned during that period, in large part, to help the development of weapons of mass destruction and care of the thousands of injured survivors of the war, abandoning in an alarming way, the cancer research. Between the years of 1918-1970, the fledgling fighting cancer took shape through research on the possible causes and treatment options. Hypothesis varied as those based on the relationship with carcinogenic substances such as tobacco, viral as the based on Peyton Roux jobs in avian sarcoma and Zur Hausen in HPV, among others, did see that probably a joint effort between a State, the scientific community and pharmaceutical companies could effectively cope with the disease through prevention, early diagnosis and timely treatment. On August 5, 1937, following a general trend in Europe led by the Institut Gustave Roussy in France and the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, the U.S. Congress enacted the founding of National Cancer Institute, considered one of the most important government agencies dedicated to oncology worldwide. During the same period in our thriving Latin America, happily oblivious to the armed conflicts of the time, wakes up the same concern: to organize a struggle state-funded against cancer, in centers going beyond just www.intervalolibre.wordpress.com July 14th, 2013 Intervalolibre holding terminally ill patients. -

Curriculum Vitae Del Dott. Mattia Intra

Curriculum vitae, Denise Mattar Fanianos, MD Place of Birth: Caracas, Venezuela Date of Birth: 16/11/1973 Citizenship: Venezuelan Languages: Spanish, English, Italian, French, Arabic In 1999 she graduated cum laude in Medicine and Surgery at the University of Caracas (Universidad Central de Venezuela- UCV, Escuela de Medicina “Luis Razetti”). In 2003 completed the residency program in General Surgery (Universidad Central de Venezuela- UCV, Hospedal “Dr. Miguel Pérez Carreño”). In 2006 completed the residency program in Surgical Oncology (Universidad Central de Venezuela- UCV, Istituto Oncologico “Luis Razetti”). In 2009 awarded the Master in Senology by University of Barcelona. Spain. In 2009 she graduated in Medicine and Surgery at the University of Milan, Italy Since 2014 is attending of the staff of the European Institute of Oncology in Milan Dr. Mattar’s main area of interest is the conservative treatment of breast cancer with special focus on radioguidel occult lesion localization (ROLL) for non palpable breast lesion, sentinel node biopsy, intraoperative radiotherapy with electrons (ELIOT) and nipple sparing mastectomy. She has participated in protocol elaboration, patient accrual, follow-up and data evaluation in several randomised clinical studies in this field. In the last 10 years, she has been invited as speaker and/or chairman in more than 30 international congresses and meetings in Europa, North and South America, Asia and Africa and she has authored several scientific publications. REFERENCES Breast Cancer in Lymphoma Survivors. In: Breast Cancer – Innovations in Research and Management: U. Veronesi, Goldhirsch A, P. Veronesi, Gentilini, MC Leonardi (eds), chapter 30, pp 399-414, Springer, 2017. Second Axillary Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy for Breast Tumor Recurrence: Experience of the European Institute of Oncology. -

Venezuela's Humanitarian Crisis

VENEZUELA’S HUMANITARIAN CRISIS Severe Medical and Food Shortages, Inadequate and Repressive Government Response Venezuela’s Humanitarian Crisis Severe Medical and Food Shortages, Inadequate and Repressive Government Response Copyright © 2016 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-34129 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org OCTOBER 2016 ISBN: 978-1-6231-34129 Venezuela’s Humanitarian Crisis Severe Medical and Food Shortages, Inadequate and Repressive Government Response Summary and Recommendations ........................................................................................ 1 A Note on Methodology .................................................................................................... 22 Shortages of Medicines and Medical Supplies ................................................................. -

Jesús Yerena: Fundador Del Museo Anatómico Del Instituto Anatómico De La Universidad Central De Venezuela

Jesús Yerena: Fundador del Museo Anatóm ico del Instituto Anatómico de la Universidad... D Loyo, C Suárez de Revista de la Facultad de Medicina, Volumen 31 - Número 1, 2008 (75-80) JESÚS YERENA: FUNDADOR DEL MUSEO ANATÓMICO DEL INSTITUTO ANATÓMICO DE LA UNIVERSIDAD CENTRAL DE VENEZUELA David Loyo Guerra1, Claudia Blandenier de Suárez2 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ RESUMEN: Se presentan los rasgos profesionales del Dr. Jesús Yerena eminente profesor de anatomía, discípulo del maestro de anatomía, el Dr. José Izquierdo. Como anatomista, Yerena le dedicó muchas horas a la disección de cadáveres humanos para conformar lo que es hoy el museo anatómico que lleva su nombre, en el Instituto Anatómico “José Izquierdo” de la Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Central de Venezuela. Igualmente se describen sus cualidades como docente de anatomía, trabajos y actuaciones como gremialista e historiador. Palabras clave: Anatomía, Disección, Museo Anatómico. ABSTRACT: The characteristics appear professionals of the eminent Dr. Jesus Yerena professor of Anatomy, disciple of the teacher of teachers of anatomy, Dr. Jose Izquierdo. Like anatomist, Yerena dedicated much hours to at him to the human corpse dissection to conform the anatomical museum that takes its name, in the Anatomical Institute “Jose Izquierdo” of the Medicine Faculty of the University City, Central University of Venezuela. Also their qualities are described with anatomy’s professor, works and performances like gremial’s and historian. Key words: Anatomy, Dissection, Anatomical Museum. INTRODUCCIÓN Hace 38 años falleció el eminente médico cirujano recibiendo el título de Doctor en Ciencias Médicas con Jesús Antonio Yerena, el 3 de julio de 1970. Dos la Tesis doctoral “Tricomoniasis vaginal”(2). -

José Gregorio Hernández, Biografía De La Ejemplaridad

llegar José Gregorio Hernández, biografía de la ejemplaridad Editores Dr. Eleazar Ontiveros Paolini Dr. Jonás Arturo Montilva Calderón Dr. Wilver Contreras Miranda Mérida-Venezuela José Gregorio Hernández, biografía de la ejemplaridad ACADEMIA DE MÉRIDA 2 José Gregorio Hernández, biografía de la ejemplaridad COLECCIÓN ACADEMIA DE MÉRIDA 2020 Academia de Mérida, la casa amarilla, casa de sapiencia… José Gregorio Hernández, biografía de la ejemplaridad Título: José Gregorio Hernández, biografía de la ejemplaridad… Editores: Eleazar Ontiveros Paolini Jonás Arturo Montilva Calderón Wilver Contreras Miranda Presentación Dr. Eleazar Ontiveros Paolini Prólogo: Fortunato González Cruz Autores: Mariano Nava Contreras, Ricardo R. Contreras, Carlos Guillermo Cárdenas Dávila, Wilver Contreras Miranda Epílogo: Ricardo Gil Otaiza Reservados todos los derechos Prohibida la reproducción total o parcial De esta obra en cualquier medio de impresión electrónico o tipográfico, sin las autorización por escrito del autor. 3 2020, Mariano Nava Contreras, Ricardo R. Contreras, Carlos Guillermo Cárdenas Dávila, Wilver Contreras Miranda. Academia de Mérida -Vicerrectorado Académico de la Universidad de Los Andes . Mérida, Venezuela. [email protected] HECHO EL DEPOSITO DE LEY Depósito Legal: ME2020000177 ISBN: 978-980-11-2018-6 ISBN-e: 978-980-11-2017-9 Corrección de estilo: María Luisa Lazzaro Diseño de cubierta y diagramación: WCM Digitalización: Laboratorio de Sostenibilidad y Ecodiseño ULA-UPV: CEFAP-LNPF Academia de Mérida, la casa amarilla, casa de sapiencia… José Gregorio Hernández, biografía de la ejemplaridad ACADEMIA DE MÉRIDA JUNTA DIRECTIVA 2020-2021 Presidente Dr. Eleazar Ontiveros Paolini Primer vicepresidente Dr. Luis Alfonso Sandia Rondón Segundo vicepresidente Dr. Ricardo Gil Otaiza Secretario Dr. José Rafael Prado P. Bibliotecario Dr. -

Breast Cancer in Venezuela: Back to the 20Th Century

World Report Breast cancer in Venezuela: back to the 20th century Facing scarcity of medicines and broken-down medical equipment, women diagnosed with breast cancer in Venezuela resort to more radical means of treatment. Hildegard Willer reports. When she realised that she could not cancer, a hormonal treatment. These which is the national public hospital for continue to afford the therapy that complementary treatments allow patients with cancer, but throughout would save her life, Dennis Mercado surgeons to preserve the breast in Venezuela, he says. According to him, felt desperate. Aged 48 years, Mercado most cases. patients wait for more than a year to get had been diagnosed with breast radiotherapy and relapses and deaths cancer 3 years before. As part of her “‘Being diagnosed with breast have increased. post-surgical treatment, she had been cancer is a shock for any Diagnostic facilities are also scarce— taking the hormonal blocker goserelin woman, but if that woman there are few functioning mammo- for several years, costing about graphy screening units in the country US$100 per month. As an internal lives in Venezuela today , it and doing immunohistochemistry is medicine specialist, Mercado urges means an endless struggle...’” complicated by the inadequate supply her patients to do everything they can of slides and reagents. Romero’s list to complete their treatment; a non- But in Venezuela, these treatments of what is missing in the Luis Razetti completed treatment scheme, Mercado are no longer available in public hospital is seemingly endless—cancer says, can be useless. But as a patient, hospitals. The country’s health system drugs, surgical instruments, syringes, she could not afford to do so. -

Antonio Paz CV 2018

Antonio Paz, MD. 60 Old New Milford Rd, Suite 3-E Brookfield, CT 06804 Professional Experience Feb, 2017 – Present Interventional Pain Management Specialist Orthopaedic Specialists of Connecticut Jan, 2011 – Aug, 2016 Medical Director, Pre-Admission Testing and Perioperative Medicine. Department of Anesthesiology, Danbury Hospital, CT Dec, 2005 – July, 2007 Hospitalist - Clinician Educator Internal Medicine Department, Norwalk Hospital Aug, 2007 – Dec, 2007 Hospitalist at Milford Hospital (Locum Tenens) Internal Medicine Department, Milford Hospital Education and Medical Training Aug, 2016 - Feb, 2017 Interventional Pain Management (Advanced Program) Comprehensive Pain & Spine Center of New York Jan, 2010 - Jan, 2011 “ Chief Resident ” Anesthesiology Residency Program (CA-3) Westchester Medical Center, New York Medical College. Jan, 2008 - Dec, 2009 Anesthesiology Residency Program (CA-1 & 2) Westchester Medical Center, New York Medical College. July, 2005 - Oct, 2005 Pulmonary and Critical Care Fellowship Program Tulane University (Interrupted by Hurricane Katrina). July, 2002 - June, 2005 Internal Medicine Residency Program (CA-1, 2 & 3) Norwalk Hospital, affiliated with Yale University School of Medicine. Oct, 1993 - March 2000 Central University of Venezuela, Luis Razetti School of Medicine, Caracas, Venezuela. Degree received: Surgical Medical Doctor (M.D.) Accreditation August 2005/2015 Certified, American Board of Internal Medicine April 2012 Certified, American Board of Anesthesiology May 2018 Certified, American Board of Pain -

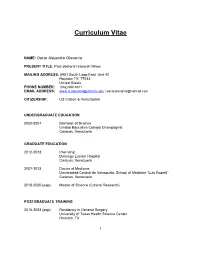

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae NAME: Oscar Alejandro Olavarria PRESENT TITLE: Post-doctoral research fellow MAILING ADDRESS: 5951 South Loop East. Unit 42 Houston TX, 77033 United States. PHONE NUMBER: (832) 690 8611 EMAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] / [email protected] CITIZENSHIP: US Citizen & Venezuelan UNDERGRADUATE EDUCATION 2002-2007 Bachelor of Science Unidad Educativa Colegio Champagnat Caracas, Venezuela GRADUATE EDUCATION 2012-2013 Internship Domingo Luciani Hospital Caracas, Venezuela 2007-2013 Doctor of Medicine Universidad Central de Venezuela, School of Medicine “Luis Razetti” Caracas, Venezuela 2018-2020 (exp) Master of Science (Clinical Research) POSTGRADUATE TRAINING 2016-2023 (exp) Residency in General Surgery University of Texas Health Science Center Houston, TX 1 2018-2020 (exp) Fellowship in Clinical Research Center for Surgical Trials and Evidence-based Practice (C-STEP) McGovern Medical School, University of Texas Health Science Center Houston, TX LICENSURE 2013 - Present Venezuelan Full Medical License 2016 - Present ECFMG Certified: #09424797 ● USMLE STEP #1: 247 points in first attempt ● USMLE STEP #2 CS: pass in first attempt ● USMLE STEP #2 CK: 236 points in first attempt ● USMLE STEP #3: 220 points in first attempt 2018 - Present Texas Medical Board - Full Medical License CERTIFICATION 2013 - Present Basic Life Support 2013 - Present Advanced Cardiac Life Support 2016 - Present Advanced Trauma Life Support 2019 Fundamentals of Laparoscopic Surgery 2020 Fundamentals of Endoscopic Surgery PROFESSIONAL ORGANIZATIONS ● American College of Surgeons - Resident Member ● American College of Surgeons, South Texas Chapter ● American Medical Association - Resident Member ● Association for Academic Surgery ● Surgical Infection Society ● Americas Hernia Society ● Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons ● Texas Medical Association ● Medical College of Venezuela ● Medical Federation of Venezuela HONORS AND AWARDS 2008 Anatomy High Academic Performance Award Universidad Central de Venezuela, School of Medicine “Dr.