DEVELOPMENT of ANTARCTIC TOURISM Tadeusz PALMOWSKI

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antarctic Peninsula Basecamp Voyages Trip Notes 2021/22

ANTARCTIC PENINSULA BASECAMP VOYAGES 2021/22 TRIP NOTES ANTARCTIC PENINSULA BASECAMP VOYAGES TRIP NOTES 2021/22 EXPEDITION DETAILS Dates: Trip 1: November 11–23, 2021 Trip 2: December 22 to January 3, 2022 Trip 3: January 3–15, 2022 Trip 4: February 24 to March 8, 2022 Trip 5: March 8–20, 2022 Duration: 13 days Departure: ex Ushuaia, Argentina Price: From US$8,500 per person Weddell Seal. Photo: Ali Liddle Antarctica is seen by many as the ‘Last Frontier’ due to its remote location and difficulty of access; this is a destination very few people have the opportunity to experience. We cross the Drake Passage in our comfortable ship before it becomes our Base Camp for daily activities such as hiking, snowshoeing, kayaking, camping, glacier walking, photo workshops and landings ashore. There is something for everyone and is an opportunity to discover Antarctica at a range of different activity levels. walks across he Antarctic landscapes, photographers to TRIP OVERVIEW explore photo opportunities, campers to enjoy life at shore base camps, kayakers to explore nearby shores, Our Antarctic journeys begin in Ushuaia, Tierra del where the ship cannot go. Passengers who do not wish Fuego, on the southern tip of Argentina. Ushuaia is to be physically active will enjoy our zodiac excursions a bustling port town and its 40,000 inhabitants are and follow the normal shore program and land nestled between the cold mountains and an even excursions—easy to moderate walks and hikes with a colder sea. ‘Downtown’ has plenty of shops including focus on wildlife. internet cafés, cafés, clothes shops, chemists and an array of good restaurants. -

Download (Pdf, 236

Science in the Snow Appendix 1 SCAR Members Full members (31) (Associate Membership) Full Membership Argentina 3 February 1958 Australia 3 February 1958 Belgium 3 February 1958 Chile 3 February 1958 France 3 February 1958 Japan 3 February 1958 New Zealand 3 February 1958 Norway 3 February 1958 Russia (assumed representation of USSR) 3 February 1958 South Africa 3 February 1958 United Kingdom 3 February 1958 United States of America 3 February 1958 Germany (formerly DDR and BRD individually) 22 May 1978 Poland 22 May 1978 India 1 October 1984 Brazil 1 October 1984 China 23 June 1986 Sweden (24 March 1987) 12 September 1988 Italy (19 May 1987) 12 September 1988 Uruguay (29 July 1987) 12 September 1988 Spain (15 January 1987) 23 July 1990 The Netherlands (20 May 1987) 23 July 1990 Korea, Republic of (18 December 1987) 23 July 1990 Finland (1 July 1988) 23 July 1990 Ecuador (12 September 1988) 15 June 1992 Canada (5 September 1994) 27 July 1998 Peru (14 April 1987) 22 July 2002 Switzerland (16 June 1987) 4 October 2004 Bulgaria (5 March 1995) 17 July 2006 Ukraine (5 September 1994) 17 July 2006 Malaysia (4 October 2004) 14 July 2008 Associate Members (12) Pakistan 15 June 1992 Denmark 17 July 2006 Portugal 17 July 2006 Romania 14 July 2008 261 Appendices Monaco 9 August 2010 Venezuela 23 July 2012 Czech Republic 1 September 2014 Iran 1 September 2014 Austria 29 August 2016 Colombia (rejoined) 29 August 2016 Thailand 29 August 2016 Turkey 29 August 2016 Former Associate Members (2) Colombia 23 July 1990 withdrew 3 July 1995 Estonia 15 June -

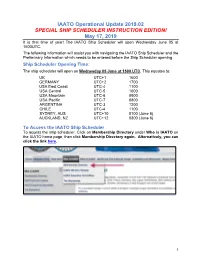

IAATO Operational Update 2019.02 SPECIAL SHIP SCHEDULER INSTRUCTION EDITION! May 17, 2019

IAATO Operational Update 2019.02 SPECIAL SHIP SCHEDULER INSTRUCTION EDITION! May 17, 2019 It is that time of year! The IAATO Ship Scheduler will open Wednesday June 05 at 1500UTC. The following information will assist you with navigating the IAATO Ship Scheduler and the Preliminary Information which needs to be entered before the Ship Scheduler opening. Ship Scheduler Opening Time: The ship scheduler will open on Wednesday 05 June at 1500 UTC. This equates to: UK UTC+1 1600 GERMANY UTC+2 1700 USA East Coast UTC-4 1100 USA Central UTC-5 1000 USA Mountain UTC-6 0900 USA Pacific UTC-7 0800 ARGENTINA UTC-3 1200 CHILE UTC-4 1100 SYDNEY, AUS UTC+10 0100 (June 6) AUCKLAND, NZ UTC+12 0300 (June 6) To Access the IAATO Ship Scheduler To access the ship scheduler, Click on Membership Directory under Who is IAATO on the IAATO home page, then click Membership Directory again. Alternatively, you can click the link here. 1 In the upper right-hand corner of the web page, there is a login button, please click on this button to gain access to the database and ship scheduler section. Remember, you will need to sign in with your Operator Login Name and Password (this is separate from the website/field staff) login. On the left-hand side of the page you will see the ship scheduler column. Alternatively, follow this direct link. http://apps.iaato.org/iaato/scheduler/. 2 Username and Password • Each company has been given one username and password for each vessel that they operate for the Ship Scheduler. -

Federal Register/Vol. 81, No. 187/Tuesday, September 27, 2016/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 81, No. 187 / Tuesday, September 27, 2016 / Notices 66301 Science Foundation, 4201 Wilson life; having prop guards on propeller Procedures for Access to Sensitive Boulevard, Arlington, Virginia 22230. tips, a flotation device if operated over Unclassified Non-Safeguards FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: water, and a ‘‘go home’’ feature in case Information,’’ published on July 5, 2016, Nature McGinn, ACA Permit Officer, at of loss of control link or low battery; see 81 FR 43661–43669, the Bellefonte the above address or ACApermits@ having an observer on the lookout for Efficiency & Sustainability Team/ nsf.gov. wildlife, people, and other hazards; and Mothers Against Tennessee River SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The ensuring that the separation between the Radiation (BEST/MATRR) filed a National Science Foundation, as operator and UAV does not exceed an Petition to Intervene and Request for directed by the Antarctic Conservation operational range of 500 meters. The Hearing on September 9, 2016. Act of 1978 (Pub. L. 95–541), as applicant is seeking a Waste Permit to The Board is comprised of the amended by the Antarctic Science, cover any accidental releases that may following Administrative Judges: Tourism and Conservation Act of 1996, result from flying a UAV. Paul S. Ryerson, Chairman, Atomic has developed regulations for the Location Safety and Licensing Board Panel, establishment of a permit system for U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Camping: Possible locations include various activities in Antarctica and Washington, DC 20555–0001 designation of certain animals and Damoy Point/Dorian Bay, Danco Island, Dr. Gary S. Arnold, Atomic Safety and ´ certain geographic areas as requiring Ronge Island, the Errera Channel, Licensing Board Panel, U.S. -

Final Report of the Thirty-Sixth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting

Final Report of the Thirty-sixth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting ANTARCTIC TREATY CONSULTATIVE MEETING Final Report of the Thirty-sixth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting Brussels, Belgium 20–29 May 2013 Volume I Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty Buenos Aires 2013 Published by: Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty Secrétariat du Traité sur l’ Antarctique Секретариат Договора об Антарктике Secretaría del Tratado Antártico Maipú 757, Piso 4 C1006ACI Ciudad Autónoma Buenos Aires - Argentina Tel: +54 11 4320 4260 Fax: +54 11 4320 4253 This book is also available from: www.ats.aq (digital version) and online-purchased copies. ISSN 2346-9897 Contents VOLUME I Acronyms and Abbreviations 9 PART I. FINAL REPORT 11 1. Final Report 13 2. CEP XVI Report 87 3. Appendices 169 ATCM XXXVI Communiqué 171 Preliminary Agenda for ATCM XXXVII 173 PART II. MEASURES, DECISIONS AND RESOLUTIONS 175 1. Measures 177 Measure 1 (2013) ASPA No 108 (Green Island, Berthelot Islands, Antarctic Peninsula): Revised Management Plan 179 Measure 2 (2013) ASPA No 117 (Avian Island, Marguerite Bay, Antarctic Peninsula): Revised Management Plan 181 Measure 3 (2013) ASPA No 123 (Barwick and Balham Valleys, Southern Victoria Land): Revised Management Plan 183 Measure 4 (2013) ASPA No 132 (Potter Peninsula, King George Island (Isla 25 de Mayo), South Shetland Islands): Revised Management Plan 185 Measure 5 (2013) ASPA No 134 (Cierva Point and offshore islands, Danco Coast, Antarctic Peninsula): Revised Management Plan 187 Measure 6 (2013) ASPA No 135 (North-east Bailey -

Waba Directory 2003

DIAMOND DX CLUB www.ddxc.net WABA DIRECTORY 2003 1 January 2003 DIAMOND DX CLUB WABA DIRECTORY 2003 ARGENTINA LU-01 Alférez de Navió José María Sobral Base (Army)1 Filchner Ice Shelf 81°04 S 40°31 W AN-016 LU-02 Almirante Brown Station (IAA)2 Coughtrey Peninsula, Paradise Harbour, 64°53 S 62°53 W AN-016 Danco Coast, Graham Land (West), Antarctic Peninsula LU-19 Byers Camp (IAA) Byers Peninsula, Livingston Island, South 62°39 S 61°00 W AN-010 Shetland Islands LU-04 Decepción Detachment (Navy)3 Primero de Mayo Bay, Port Foster, 62°59 S 60°43 W AN-010 Deception Island, South Shetland Islands LU-07 Ellsworth Station4 Filchner Ice Shelf 77°38 S 41°08 W AN-016 LU-06 Esperanza Base (Army)5 Seal Point, Hope Bay, Trinity Peninsula 63°24 S 56°59 W AN-016 (Antarctic Peninsula) LU- Francisco de Gurruchaga Refuge (Navy)6 Harmony Cove, Nelson Island, South 62°18 S 59°13 W AN-010 Shetland Islands LU-10 General Manuel Belgrano Base (Army)7 Filchner Ice Shelf 77°46 S 38°11 W AN-016 LU-08 General Manuel Belgrano II Base (Army)8 Bertrab Nunatak, Vahsel Bay, Luitpold 77°52 S 34°37 W AN-016 Coast, Coats Land LU-09 General Manuel Belgrano III Base (Army)9 Berkner Island, Filchner-Ronne Ice 77°34 S 45°59 W AN-014 Shelves LU-11 General San Martín Base (Army)10 Barry Island in Marguerite Bay, along 68°07 S 67°06 W AN-016 Fallières Coast of Graham Land (West), Antarctic Peninsula LU-21 Groussac Refuge (Navy)11 Petermann Island, off Graham Coast of 65°11 S 64°10 W AN-006 Graham Land (West); Antarctic Peninsula LU-05 Melchior Detachment (Navy)12 Isla Observatorio -

Danco Island, Neumayer Channel & Damoy Point

Wednesday, March 7th, 2018 Antarctic Explorer: Discovering the 7th Continent Aboard the M/V Ocean Endeavour Danco Island, Neumayer Channel & Damoy Point “Men wanted for hazardous journey, small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in case of success.” -Sir Ernest Shackleton’s alleged advertisement for crew of the Endurance Expedition 06:30 Early morning coffee, tea and pastries are available in the Compass Club 07:30 – 09:00 Breakfast is served in the Polaris Restaurant 09:30 We plan to land & zodiac cruise at Danco Island Danco Island lies in the southern end of the Errera Channel. It is relatively small, 1.6 km (1 mi) long, and 180 m (590 ft) high. The view from the top of Danco Island is spectacular due to the heavily crevassed glaciers in the surrounding mountains. Beautiful rolled icebergs also tend to collect in this area of the channel. Danco Island is home to approximately 1,600 breeding pairs of gentoo penguins, which breed on the steep slopes. Disembarkation Sequence: 1) Penguin 2) Albatross 3) Whale 4) Seal 12:30 – 13:30 Lunch is served in the Polaris Restaurant 14:00 We plan to ship cruise the Neumayer Channel This 26km (16 mi) long and 2.4km (1.5mile) wide channel separates Anvers Island from Wiencke & Doumer Islands. It was first seen by the German Antarctic Expedition (1873-74) but was first transited by the Belgian Antarctic Expedition under de Gerlache on the Belgica (1897-99). They named it for Georg von Neuymayer a German geophysicist and advocate of Antarctic exploration. -

Antarctica Classic II: the Falklands, South Georgia & Antarctica 30 Nov - 18 Dec 2017 (19 Days) Trip Report

Antarctica Classic II: The Falklands, South Georgia & Antarctica 30 Nov - 18 Dec 2017 (19 Days) Trip Report Humpback Whale by Holly Faithfull Trip report compiled by Tour Leader, Holly Faithfull Rockjumper Birding Tours View more tours to Antarctica Trip Report – RBL Antarctica - Classic II 2017 2 Tour Summary Rockjumper’s Classic Antarctica II adventure started in Ushuaia, the most southerly city in the world. Late afternoon we boarded the Akademik Ioffe, a Russian research vessel, and our wonderfully stable home for this adventure to the south. Day 1, 30 Nov: Ushuaia harbour and Beagle channel. We were late sailing out of the harbour due to high winds, but we made the most of the daylight as we scanned from the bows for our first species. Leaving Ushuaia Harbour, we saw Southern Crested Caracara, Chilean Skua, Kelp Gull and South American Tern, as well as Dolphin Gull, and both Rock and Imperial Shags. Magellanic Penguin escorted us along the Beagle Channel, and our first (of many) Black-browed Albatross and Wilson's Storm Petrel were seen, together with Sooty Shearwater, Southern Giant Petrel, Southern Fulmar and White-chinned Petrel. A beautiful sunset around 10pm ended our first exciting day on board the ship. Day 2, 1 Dec: At sea south-west of Falkland Kelp Geese by Holly Faithfull Islands (South Atlantic Ocean). Fortunately, the wind was behind us and the seas were fairly calm for our first full day at sea, but there was enough swell for plenty of seabirds, including many Black-browed Albatrosses, White-chinned Petrels and Sooty Shearwaters. -

Final Report of the XXXIV ATCM

Final Report of the Thirty-fourth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting ANTARCTIC TREATY CONSULTATIVE MEETING Final Report of the Thirty-fourth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting Buenos Aires, 20 June – 1 July 2011 Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty Buenos Aires 2011 Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (34th : 2011 : Buenos Aires) Final Report of the Thirty-fourth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting. Buenos Aires, Argentina, 20 June–1 July 2011. Buenos Aires : Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty, 2011. 348 p. ISBN 978-987-1515-26-4 1. International law – Environmental issues. 2. Antarctic Treaty system. 3. Environmental law – Antarctica. 4. Environmental protection – Antarctica. DDC 341.762 5 ISBN 978-987-1515-26-4 Contents VOLUME 1 (in hard copy and CD) Acronyms and Abbreviations 9 PART I. FINAL REPORT 11 1. Final Report 13 2. CEP XIV Report 91 3. Appendices 175 Declaration on Antarctic Cooperation 177 Preliminary Agenda for ATCM XXXV 179 PART II. MEASURES, DECISIONS AND RESOLUTIONS 181 1. Measures 183 Measure 1 (2011) ASPA 116 (New College Valley, Caughley Beach, Cape Bird, Ross Island): Revised Management Plan 185 Measure 2 (2011) ASPA 120 (Pointe-Géologie Archipelago, Terre Adélie): Revised Management Plan 187 Measure 3 (2011) ASPA 122 (Arrival Heights, Hut Point Peninsula, Ross Island): Revised Management Plan 189 Measure 4 (2011) ASPA 126 (Byers Peninsula, Livingston Island, South Shetland Islands): Revised Management Plan 191 Measure 5 (2011) ASPA 127 (Haswell Island): Revised Management Plan 193 Measure 6 (2011) ASPA 131 -

Across the Antarctic Circle

Across the Antarctic Circle 4 – 15 February 2020 | Greg Mortimer About Us Aurora Expeditions embodies the spirit of adventure, travelling to some of the most wild opportunity for adventure and discovery. Our highly experienced expedition team of and remote places on our planet. With over 28 years’ experience, our small group voyages naturalists, historians and destination specialists are passionate and knowledgeable – they allow for a truly intimate experience with nature. are the secret to a fulfilling and successful voyage. Our expeditions push the boundaries with flexible and innovative itineraries, exciting Whilst we are dedicated to providing a ‘trip of a lifetime’, we are also deeply committed to wildlife experiences and fascinating lectures. You’ll share your adventure with a group education and preservation of the environment. Our aim is to travel respectfully, creating of like-minded souls in a relaxed, casual atmosphere while making the most of every lifelong ambassadors for the protection of our destinations. DAY 1 | Tuesday 4 February 2020 Ushuaia Position: 20:22 hours Course: 290.6° Wind Speed: 19 knots Barometer: 756 MB & steady Latitude: 54°48.00’ S Speed: At Anchor Wind Direction: NW Air Temp: 15° C Longitude: 068°18.03’ W Sea Temp: 214 C Dare to live the life you have dreamed for yourself. Go forward and make your We learned of some unexpected news: that we would have a bonus day in Ushuaia as dreams come true. — Ralph Waldo Emerson we awaited additional fortifications to our hull from minor damage incurred earlier ni the season. While it came as a bit of surprise, this is a mark of true expedition and adventure. -

Grand Circle Corporation

IEE Antarctic Peninsula Cruise Program – MV Corinthian Multi-year Assessment Grand Circle Corporation Initial Environmental Evaluation for Antarctic Peninsula Ship-based Tourism Aboard MV Corinthian Five-year Programmatic Assessment December 2014 – March 2019 Submitted 12 September 2017 to US Environmental Protection Agency for Activities during the 2017-18 Season Grand Circle Corporation Page 1 IEE Antarctic Peninsula Cruise Program – MV Corinthian Multi-year Assessment TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. CONTACT DETAILS ................................................................................................................................................ 5 2. NON TECHNICAL SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................ 6 2.1 Description of the Proposed Activity ................................................................................................................. 7 2.2 Alternatives ........................................................................................................................................................ 8 2.3 Assessment of Potential Impacts ....................................................................................................................... 8 2.4 Minimization and Mitigation ............................................................................................................................. 9 2.5 Conclusion ......................................................................................................................................................... -

Antarctic Expedition

Antarctic Expedition 11 Days Antarctic Expedition Take a once-in-a-lifetime journey to the "last continent", an unspoiled landscape of glaciers and icy pristine waters. Cross the Drake Passage by ship and prep for the adventure with engaging talks and presentations. Once there, sea conditions determine the itinerary, but our ships call on remarkable places such as Deception Island — a volcanic caldera that we can sail into — and Paradise Bay, a favorite spot for Zodiac cruising to see fantastical iceberg sculptures. Opportunities abound to see penguins, seals, seabirds, and whales, who raise their young in this frozen paradise. Details Testimonials Arrive: Ushuaia, Argentina "I've taken six MTS trips and they have all exceeded my expectations. Depart: Ushuaia, Argentina The staff, the food, the logistics and the communications have always been Duration: 11 Days exceptional. Thank you for being my "go to" adventure travel company!" Group Size: Up to 96 Guests Margaret I. Minimum Age: 10 Years Old "I have traveled extensively around the Activity Level: Level 1 world. The experience with MTS was by . far the best I have ever had. Thank you for such excellence." Marianne W. REASON #01 REASON #02 REASON #03 MT Sobek's Polar Value We include emergency medical Over 30 years offering polar Promise means that we offer insurance and emergency evacuation voyages we have built strong in-house services to help coverage as a value-added benefit relationships with polar plan and execute you polar at no additional cost to you. outfitters and ships that adventure for no added cost. cruise the 7th continent.