Spatial Patterns of Tour Ship Traffic in the Antarctic Peninsula Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antarctic Peninsula Basecamp Voyages Trip Notes 2021/22

ANTARCTIC PENINSULA BASECAMP VOYAGES 2021/22 TRIP NOTES ANTARCTIC PENINSULA BASECAMP VOYAGES TRIP NOTES 2021/22 EXPEDITION DETAILS Dates: Trip 1: November 11–23, 2021 Trip 2: December 22 to January 3, 2022 Trip 3: January 3–15, 2022 Trip 4: February 24 to March 8, 2022 Trip 5: March 8–20, 2022 Duration: 13 days Departure: ex Ushuaia, Argentina Price: From US$8,500 per person Weddell Seal. Photo: Ali Liddle Antarctica is seen by many as the ‘Last Frontier’ due to its remote location and difficulty of access; this is a destination very few people have the opportunity to experience. We cross the Drake Passage in our comfortable ship before it becomes our Base Camp for daily activities such as hiking, snowshoeing, kayaking, camping, glacier walking, photo workshops and landings ashore. There is something for everyone and is an opportunity to discover Antarctica at a range of different activity levels. walks across he Antarctic landscapes, photographers to TRIP OVERVIEW explore photo opportunities, campers to enjoy life at shore base camps, kayakers to explore nearby shores, Our Antarctic journeys begin in Ushuaia, Tierra del where the ship cannot go. Passengers who do not wish Fuego, on the southern tip of Argentina. Ushuaia is to be physically active will enjoy our zodiac excursions a bustling port town and its 40,000 inhabitants are and follow the normal shore program and land nestled between the cold mountains and an even excursions—easy to moderate walks and hikes with a colder sea. ‘Downtown’ has plenty of shops including focus on wildlife. internet cafés, cafés, clothes shops, chemists and an array of good restaurants. -

South Georgia & Antarctic Odyssey

South Georgia & Antarctic Odyssey 16 January – 02 February 2019 | Polar Pioneer About Us Aurora Expeditions embodies the spirit of adventure, travelling to some of the most wild and adventure and discovery. Our highly experienced expedition team of naturalists, historians and remote places on our planet. With over 27 years’ experience, our small group voyages allow for destination specialists are passionate and knowledgeable – they are the secret to a fulfilling a truly intimate experience with nature. and successful voyage. Our expeditions push the boundaries with flexible and innovative itineraries, exciting wildlife Whilst we are dedicated to providing a ‘trip of a lifetime’, we are also deeply committed to experiences and fascinating lectures. You’ll share your adventure with a group of like-minded education and preservation of the environment. Our aim is to travel respectfully, creating souls in a relaxed, casual atmosphere while making the most of every opportunity for lifelong ambassadors for the protection of our destinations. DAY 1 | Wednesday 16 January 2019 Ushuaia; Beagle Channel Position: 19:38 hours Course: 106° Wind Speed: 12 knots Barometer: 1006.6 hPa & steady Latitude: 54° 51’ S Speed: 12 knots Wind Direction: W Air Temp: 11°C Longitude: 68° 02’ W Sea Temp: 7°C The land was gone, all but a little streak, away off on the edge of the water, and We explored the decks, ventured down to the dining rooms for tea and coffee, then climbed down under us was just ocean, ocean, ocean—millions of miles of it, heaving up and down the various staircases. Howard then called us together to introduce the Aurora team and give a lifeboat and safety briefing. -

Antarctic Primer

Antarctic Primer By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller Designed by: Olivia Young, Aurora Expeditions October 2018 Cover image © I.Tortosa Morgan Suite 12, Level 2 35 Buckingham Street Surry Hills, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia To anyone who goes to the Antarctic, there is a tremendous appeal, an unparalleled combination of grandeur, beauty, vastness, loneliness, and malevolence —all of which sound terribly melodramatic — but which truly convey the actual feeling of Antarctica. Where else in the world are all of these descriptions really true? —Captain T.L.M. Sunter, ‘The Antarctic Century Newsletter ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 3 CONTENTS I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic Antarctica’s Historic Heritage South Georgia Biosecurity II. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Antarctica The Southern Ocean The Continent Climate Atmospheric Phenomena The Ozone Hole Climate Change Sea Ice The Antarctic Ice Cap Icebergs A Short Glossary of Ice Terms III. THE BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT Life in Antarctica Adapting to the Cold The Kingdom of Krill IV. THE WILDLIFE Antarctic Squids Antarctic Fishes Antarctic Birds Antarctic Seals Antarctic Whales 4 AURORA EXPEDITIONS | Pioneering expedition travel to the heart of nature. CONTENTS V. EXPLORERS AND SCIENTISTS The Exploration of Antarctica The Antarctic Treaty VI. PLACES YOU MAY VISIT South Shetland Islands Antarctic Peninsula Weddell Sea South Orkney Islands South Georgia The Falkland Islands South Sandwich Islands The Historic Ross Sea Sector Commonwealth Bay VII. FURTHER READING VIII. WILDLIFE CHECKLISTS ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 5 Adélie penguins in the Antarctic Peninsula I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Antarctica is the largest wilderness area on earth, a place that must be preserved in its present, virtually pristine state. -

Barrientos Island (Aitcho Islands) ANTARCTIC TREATY King George Is

Barrientos Island (Aitcho Islands) ANTARCTIC TREATY King George Is. Barrientos Island visitor site guide Ferraz Station Turret Point (Aitcho Islands) Admiralty Bay Elephant Is. Maxwell Bay Penguin Island 62˚24’S, 59˚47’W - North entrance to English Strait Marsh/frei Stations Great Wall Station between Robert and Greenwich Islands. Bellingshausen Station Arctowski Station Artigas Station Jubany Station King Sejong Station Potter Cove Key features AITCHO Nelson Is. ISLANDRobert Is. - Gentoo and Chinstrap Penguins S Mitchell Cove - Southern Elephant Seals Greenwich Is. Robert Point - Geological features Fort Point Half Moon Is. Yankee Harbour - Southern Giant Petrels Livingston Is. - Vegetation Hannah Point Bransfield Strait Snow Is. Telefon Bay Pendulum Cove Gourdin Is. Deception Is. Baily Head Description Vapour Col Cape Whaler's Bay Dubouzet B. O'higgins Station TOPOGRAPHY This 1.5km island’s north coast is dominated by steep cliffs, reaching a height of approximatelyAstr 70olabe Cape Hope metres, with a gentle slope down to the south coast. The eastern and western ends of the island Island are Legoupil Bay black sand and cobbled beaches. Columnar basalt outcrops are a notable feature of the western end. a insul FAUNA Confirmed breeders: Gentoo penguin (Pygoscelis papua), chinstrap penguin (Pygoscelis antarctica), Pen inity southern giant petrel (Macronectes giganteus), kelp gull (LarusNorthwest dominicanus (Nw)), and skuas (Catharacta spp.). Tr Suspected breeders: Blue-eyed shag (Phalacrocorax atricepsSubar) andea Wilson’s storm-petrel (OceanitesBone Bay Tower Is. oceanicus). Regularly haul out: Weddell seals (Leptonychotes weddellii), southern elephant seals (Mirounga leonina), and from late December, Antarctic fur seals (Arctocephalus Trgazellainity Is. ). Charcot Bay FLORA The entire centre of the island is covered by a very extensive moss carpet. -

Download (Pdf, 236

Science in the Snow Appendix 1 SCAR Members Full members (31) (Associate Membership) Full Membership Argentina 3 February 1958 Australia 3 February 1958 Belgium 3 February 1958 Chile 3 February 1958 France 3 February 1958 Japan 3 February 1958 New Zealand 3 February 1958 Norway 3 February 1958 Russia (assumed representation of USSR) 3 February 1958 South Africa 3 February 1958 United Kingdom 3 February 1958 United States of America 3 February 1958 Germany (formerly DDR and BRD individually) 22 May 1978 Poland 22 May 1978 India 1 October 1984 Brazil 1 October 1984 China 23 June 1986 Sweden (24 March 1987) 12 September 1988 Italy (19 May 1987) 12 September 1988 Uruguay (29 July 1987) 12 September 1988 Spain (15 January 1987) 23 July 1990 The Netherlands (20 May 1987) 23 July 1990 Korea, Republic of (18 December 1987) 23 July 1990 Finland (1 July 1988) 23 July 1990 Ecuador (12 September 1988) 15 June 1992 Canada (5 September 1994) 27 July 1998 Peru (14 April 1987) 22 July 2002 Switzerland (16 June 1987) 4 October 2004 Bulgaria (5 March 1995) 17 July 2006 Ukraine (5 September 1994) 17 July 2006 Malaysia (4 October 2004) 14 July 2008 Associate Members (12) Pakistan 15 June 1992 Denmark 17 July 2006 Portugal 17 July 2006 Romania 14 July 2008 261 Appendices Monaco 9 August 2010 Venezuela 23 July 2012 Czech Republic 1 September 2014 Iran 1 September 2014 Austria 29 August 2016 Colombia (rejoined) 29 August 2016 Thailand 29 August 2016 Turkey 29 August 2016 Former Associate Members (2) Colombia 23 July 1990 withdrew 3 July 1995 Estonia 15 June -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 78/Tuesday, April 23, 2019/Rules

Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 78 / Tuesday, April 23, 2019 / Rules and Regulations 16791 U.S.C. 3501 et seq., nor does it require Agricultural commodities, Pesticides SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The any special considerations under and pests, Reporting and recordkeeping Antarctic Conservation Act of 1978, as Executive Order 12898, entitled requirements. amended (‘‘ACA’’) (16 U.S.C. 2401, et ‘‘Federal Actions to Address Dated: April 12, 2019. seq.) implements the Protocol on Environmental Justice in Minority Environmental Protection to the Richard P. Keigwin, Jr., Populations and Low-Income Antarctic Treaty (‘‘the Protocol’’). Populations’’ (59 FR 7629, February 16, Director, Office of Pesticide Programs. Annex V contains provisions for the 1994). Therefore, 40 CFR chapter I is protection of specially designated areas Since tolerances and exemptions that amended as follows: specially managed areas and historic are established on the basis of a petition sites and monuments. Section 2405 of under FFDCA section 408(d), such as PART 180—[AMENDED] title 16 of the ACA directs the Director the tolerance exemption in this action, of the National Science Foundation to ■ do not require the issuance of a 1. The authority citation for part 180 issue such regulations as are necessary proposed rule, the requirements of the continues to read as follows: and appropriate to implement Annex V Regulatory Flexibility Act (5 U.S.C. 601 Authority: 21 U.S.C. 321(q), 346a and 371. to the Protocol. et seq.) do not apply. ■ 2. Add § 180.1365 to subpart D to read The Antarctic Treaty Parties, which This action directly regulates growers, as follows: includes the United States, periodically food processors, food handlers, and food adopt measures to establish, consolidate retailers, not States or tribes. -

In Shackleton's Footsteps

In Shackleton’s Footsteps 20 March – 06 April 2019 | Polar Pioneer About Us Aurora Expeditions embodies the spirit of adventure, travelling to some of the most wild and adventure and discovery. Our highly experienced expedition team of naturalists, historians and remote places on our planet. With over 27 years’ experience, our small group voyages allow for destination specialists are passionate and knowledgeable – they are the secret to a fulfilling a truly intimate experience with nature. and successful voyage. Our expeditions push the boundaries with flexible and innovative itineraries, exciting wildlife Whilst we are dedicated to providing a ‘trip of a lifetime’, we are also deeply committed to experiences and fascinating lectures. You’ll share your adventure with a group of like-minded education and preservation of the environment. Our aim is to travel respectfully, creating souls in a relaxed, casual atmosphere while making the most of every opportunity for lifelong ambassadors for the protection of our destinations. DAY 1 | Wednesday 20 March 2019 Ushuaia, Beagle Channel Position: 21:50 hours Course: 84° Wind Speed: 5 knots Barometer: 1007.9 hPa & falling Latitude: 54°55’ S Speed: 9.4 knots Wind Direction: E Air Temp: 11°C Longitude: 67°26’ W Sea Temp: 9°C Finally, we were here, in Ushuaia aboard a sturdy ice-strengthened vessel. At the wharf Gary Our Argentinian pilot climbed aboard and at 1900 we cast off lines and eased away from the and Robyn ticked off names, nabbed our passports and sent us off to Kathrine and Scott for a wharf. What a feeling! The thriving city of Ushuaia receded as we motored eastward down the quick photo before boarding Polar Pioneer. -

Yankee Harbour ANTARCTIC King George Is

Yankee Harbour ANTARCTIC King George Is. TREATY Ferraz Station Turret Point Yankee Harbour visitor siteAdmiralty guide Bay Elephant Is. Maxwell Bay Penguin Island 62˚32’S, 59˚47’W - South-western Greenwich Island. Marsh/frei Stations Great Wall Station Bellingshausen Station Arctowski Station Artigas Station Jubany Station King Sejong Station Potter Cove Key features Aitcho Islands Nelson Is. Robert Is. - Gentoo Penguins Mitchell Cove Greenwich Is. Robert Point Fort Point - Open walking areas Half Moon Is. YANKEE HARBOUR Livingston Is. - Artefacts from sealing operations Hannah Point Bransfield Strait Snow Is. Telefon Bay Pendulum Cove Gourdin Is. Deception Is. Baily Head Vapour Col Cape Whaler's Bay Dubouzet B. O'higgins Station Description Astrolabe Cape Hope Island Legoupil Bay TOPOGRAPHY A small glacial-edged harbour, enclosed by a curved gravel spit. A large terraced beach area includes a a insul melt-pool to the east. Beyond the beach, steep scree slopes rise to a rugged knife-edge summit. Pen inity FAUNA Confirmed breeders: Gentoo penguin (Pygoscelis papua) andNorthwest skuas (Catharacta, (Nw) spp.). Suspected Tr breeders: Snowy sheathbill (Chionis alba) and Wilson’s storm-petrel (Oceanites oceanicus). Regularly haul Subarea Bone Bay out: Southern elephant seals (Mirounga leonina), Weddell seals (LeptonychotesTower weddellii Is. ), and Antarctic fur seals (Arctocephalus gazella). FLORA Deschampsia antarctica, Colobanthus quitensis, swards of moss species, Xanthoria spp. and other Trinity Is. Charcot crustose lichens, and the green alga Prasiola crispa. Bay OTHER Artefacts from early sealing activities may be found along the inner shoreline. Mikklesen Harbor Visitor Impact KNOWN IMPACTS None. POTENTIAL IMPACTS Disturbance of wildlife, damage to the sealing remains and trampling vegetation. -

Numbers of Adelie Penguins Breeding at Hope Bay and Seymour Island Rookeries (West Antarctica) in 1985

POLISH POLAR RESEARCH (POL. POLAR RES.) 8 4 411—422. 1987 Andrzej MYRCHA", Andrzej TATUR2» and Rodolfo del VALLE3) " Institute of Biology, Warsaw University, Branch in Białystok, 64 Sosnowa. 15-887 Białystok, POLAND 2) Department of Biogeochemistry, Institute of Ecology, Polish Academy of Sciences, Dziekanów Leśny. 05-092 Łomianki. POLAND 31 Instituto Antarctico Ąrgcntino, Cerrito 1248. Capital Federal, ARGENTINA Numbers of Adelie penguins breeding at Hope Bay and Seymour Island rookeries (West Antarctica) in 1985 ABSTRACT: At the turn of October 1985, the abundance of breeding Adelie penguins was estimated at the Hope Bay oasis on the Antarctic Peninsula and on Seymour Island. In the Hope Bay rookery, 123850 pairs of penguins were recorded, beginning their breeding at the end of October. Data so far obtained indicate a continuous increase in the number of birds sat this rookery. On the other hand, the Seymour Island colony consisted of 21954 pairs of Adelie penguins. Clear differences in the geomorphological structure of areas occupied by penguins in those two places are discussed. No gentoo penguins were detected in either of the colonies. Key words: Antarctica. Hope Bay, Seymour Island, Adelie penguins. 1. Introduction Birds occurring in south polar regions for long have attracted much attention due to their importance in the functioning of the marine Antarctic ecosystem. The great abundance of these few species makes them play a significant role in the economy of energy of the Southern Ocean (Croxall 1984, Laws 1985). Among these birds penguins are dominant, comprising over 90% of the bird biomass in this region. The Adelie penguins, in turn, are one of the most numerous of the Antarctic species. -

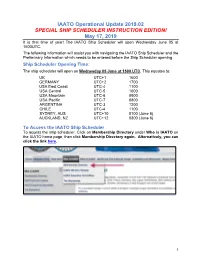

IAATO Operational Update 2019.02 SPECIAL SHIP SCHEDULER INSTRUCTION EDITION! May 17, 2019

IAATO Operational Update 2019.02 SPECIAL SHIP SCHEDULER INSTRUCTION EDITION! May 17, 2019 It is that time of year! The IAATO Ship Scheduler will open Wednesday June 05 at 1500UTC. The following information will assist you with navigating the IAATO Ship Scheduler and the Preliminary Information which needs to be entered before the Ship Scheduler opening. Ship Scheduler Opening Time: The ship scheduler will open on Wednesday 05 June at 1500 UTC. This equates to: UK UTC+1 1600 GERMANY UTC+2 1700 USA East Coast UTC-4 1100 USA Central UTC-5 1000 USA Mountain UTC-6 0900 USA Pacific UTC-7 0800 ARGENTINA UTC-3 1200 CHILE UTC-4 1100 SYDNEY, AUS UTC+10 0100 (June 6) AUCKLAND, NZ UTC+12 0300 (June 6) To Access the IAATO Ship Scheduler To access the ship scheduler, Click on Membership Directory under Who is IAATO on the IAATO home page, then click Membership Directory again. Alternatively, you can click the link here. 1 In the upper right-hand corner of the web page, there is a login button, please click on this button to gain access to the database and ship scheduler section. Remember, you will need to sign in with your Operator Login Name and Password (this is separate from the website/field staff) login. On the left-hand side of the page you will see the ship scheduler column. Alternatively, follow this direct link. http://apps.iaato.org/iaato/scheduler/. 2 Username and Password • Each company has been given one username and password for each vessel that they operate for the Ship Scheduler. -

Federal Register/Vol. 81, No. 187/Tuesday, September 27, 2016/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 81, No. 187 / Tuesday, September 27, 2016 / Notices 66301 Science Foundation, 4201 Wilson life; having prop guards on propeller Procedures for Access to Sensitive Boulevard, Arlington, Virginia 22230. tips, a flotation device if operated over Unclassified Non-Safeguards FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: water, and a ‘‘go home’’ feature in case Information,’’ published on July 5, 2016, Nature McGinn, ACA Permit Officer, at of loss of control link or low battery; see 81 FR 43661–43669, the Bellefonte the above address or ACApermits@ having an observer on the lookout for Efficiency & Sustainability Team/ nsf.gov. wildlife, people, and other hazards; and Mothers Against Tennessee River SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The ensuring that the separation between the Radiation (BEST/MATRR) filed a National Science Foundation, as operator and UAV does not exceed an Petition to Intervene and Request for directed by the Antarctic Conservation operational range of 500 meters. The Hearing on September 9, 2016. Act of 1978 (Pub. L. 95–541), as applicant is seeking a Waste Permit to The Board is comprised of the amended by the Antarctic Science, cover any accidental releases that may following Administrative Judges: Tourism and Conservation Act of 1996, result from flying a UAV. Paul S. Ryerson, Chairman, Atomic has developed regulations for the Location Safety and Licensing Board Panel, establishment of a permit system for U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, Camping: Possible locations include various activities in Antarctica and Washington, DC 20555–0001 designation of certain animals and Damoy Point/Dorian Bay, Danco Island, Dr. Gary S. Arnold, Atomic Safety and ´ certain geographic areas as requiring Ronge Island, the Errera Channel, Licensing Board Panel, U.S. -

Final Report of the Thirty-Sixth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting

Final Report of the Thirty-sixth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting ANTARCTIC TREATY CONSULTATIVE MEETING Final Report of the Thirty-sixth Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting Brussels, Belgium 20–29 May 2013 Volume I Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty Buenos Aires 2013 Published by: Secretariat of the Antarctic Treaty Secrétariat du Traité sur l’ Antarctique Секретариат Договора об Антарктике Secretaría del Tratado Antártico Maipú 757, Piso 4 C1006ACI Ciudad Autónoma Buenos Aires - Argentina Tel: +54 11 4320 4260 Fax: +54 11 4320 4253 This book is also available from: www.ats.aq (digital version) and online-purchased copies. ISSN 2346-9897 Contents VOLUME I Acronyms and Abbreviations 9 PART I. FINAL REPORT 11 1. Final Report 13 2. CEP XVI Report 87 3. Appendices 169 ATCM XXXVI Communiqué 171 Preliminary Agenda for ATCM XXXVII 173 PART II. MEASURES, DECISIONS AND RESOLUTIONS 175 1. Measures 177 Measure 1 (2013) ASPA No 108 (Green Island, Berthelot Islands, Antarctic Peninsula): Revised Management Plan 179 Measure 2 (2013) ASPA No 117 (Avian Island, Marguerite Bay, Antarctic Peninsula): Revised Management Plan 181 Measure 3 (2013) ASPA No 123 (Barwick and Balham Valleys, Southern Victoria Land): Revised Management Plan 183 Measure 4 (2013) ASPA No 132 (Potter Peninsula, King George Island (Isla 25 de Mayo), South Shetland Islands): Revised Management Plan 185 Measure 5 (2013) ASPA No 134 (Cierva Point and offshore islands, Danco Coast, Antarctic Peninsula): Revised Management Plan 187 Measure 6 (2013) ASPA No 135 (North-east Bailey