Thesis Critical Influences Affecting the Contemporary Brass Playing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brass Teacherõs Guide

Teacher’s Guide Brass ® by Robert W.Getchell, Ph. D. Foreword This manual includes only the information most pertinent to the techniques of teaching and playing the instruments of the brass family. Its principal objective is to be of practical help to the instrumental teacher whose major instrument is not brass. In addition, the contents have purposely been arranged to make the manual serve as a basic text for brass technique courses at the college level. The manual should also help the brass player to understand the technical possibilities and limitations of his instrument. But since it does not pretend to be an exhaustive study, it should be supplemented in this last purpose by additional explanation from the instructor or additional reading by the student. General Characteristics of all Brass Instruments Of the many wind instruments, those comprising the brass family are perhaps the most closely interrelated as regards principles of tone production, embouchure, and acoustical characteristics. A discussion of the characteristics common to all brass instruments should be helpful in clarifying certain points concerning the individual instruments of the brass family to be discussed later. TONE PRODUCTION. The principle of tone production in brass instruments is the lip-reed principle, peculiar to instruments of the brass family, and characterized by the vibration of the lip or lips which sets the sound waves in motion. One might describe the lip or lips as the generator, the tubing of the instrument as the resonator, and the bell of the instrument as the amplifier. EMBOUCHURE. It is imperative that prospective brass players be carefully selected, as perhaps the most important measure of success or failure in a brass player, musicianship notwithstanding, is the degree of flexibility and muscular texture in his lips. -

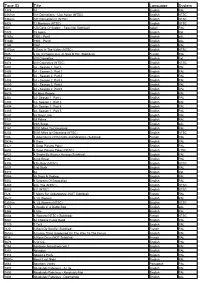

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society

Capri Community Film Society Papers Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society Auburn University at Montgomery Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library Written By: Rickey Best & Jason Kneip Last Updated: 2/19/2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2-3 Index Terms 3 Agency History 3-4 1 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Scope and Content 5 Arrangement 5-10 Inventory 10- Collection Summary Creator: Capri Community Film Society Title: Capri Community Film Society Papers Dates: 1983-present Quantity: 6 boxes; 6.0 cu. Ft. Identification: 92/2 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Capri Community Film Society Papers, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: The collection began with an initial transfer on September 19, 1991. A second donation occurred in February, 1995. Since then, regular donations of papers occur on a yearly basis. Processed By: Jermaine Carstarphen, Student Assistant & Rickey Best, Archivist/Special Collections Librarian (1993); Jason Kneip, Archives/Special Collections Librarian. Samantha McNeilly, Archives/Special Collections Assistant. 2 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Restrictions Restrictions on access: Access to membership files is closed for 25 years from date of donation. Restrictions on usage: Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public domain. Index Terms The material is indexed under the following headings in the Auburn University at Montgomery’s Library catalogs – online and offline. -

The Hard Bop Trombone: an Exploration of the Improvisational Styles of the Four Trombonist Who Defined the Genre (1955-1964)

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2019 The Hard Bop Trombone: An exploration of the improvisational styles of the four trombonist who defined the genre (1955-1964) Emmett Curtis Goods West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Goods, Emmett Curtis, "The Hard Bop Trombone: An exploration of the improvisational styles of the four trombonist who defined the genre (1955-1964)" (2019). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7464. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7464 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Hard Bop Trombone: An exploration of the improvisational styles of the four trombonist who defined the genre (1955-1964) Emmett C. Goods Dissertation submitted to the School of Music at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Trombone Performance H. -

King's Film Society Past Films 1992 –

King’s Film Society Past Films 1992 – Fall 1992 Truly, Madly, Deeply Sept. 8 Howard’s End Oct. 13 Search for Intelligent Signs of Life In the Universe Oct. 27 Europa, Europa Nov. 10 Spring 1993 A Woman’s Tale April 13 Everybody’s Fine May 4 My Father’s Glory May 11 Buried on Sunday June 8 Fall 1993 Enchanted April Oct. 5 Cinema Paradiso Oct. 26 The Long Day Closes Nov. 9 The Last Days of Chez-Nous Nov. 23 Much Ado About Nothing Dec. 7 Spring 1994 Strictly Ballroom April 12 Raise the Red Lantern April 26 Like Water for Chocolate May 24 In the Name of the Father June 14 The Joy Luck Club June 28 Fall 1994 The Wedding Banquet Sept 13 The Scent of Green Papaya Sept. 27 Widow’s Peak Oct. 9 Sirens Oct. 25 The Snapper Nov. 8 Madame Sousatzka Nov. 22 Spring 1995 Whale Music April 11 The Madness of King George April 25 Three Colors: Red May 9 To Live May 23 Hoop Dreams June 13 Priscilla: Queen of the Desert June 27 Fall 1995 Strawberry & Chocolate Sept. 26 Muriel’s Wedding Oct. 10 Burnt by the Sun Oct. 24 When Night Rain Is Falling Nov. 14 Before the Rain Nov. 28 Il Postino Dec. 12 Spring 1996 Eat Drink Man Woman March 25 The Mystery of Rampo April 9 Smoke April 23 Le Confessional May 14 A Month by the Lake May 28 Persuasion June 11 Fall 1996 Antonia’s Line Sept. 24 Cold Comfort Farm Oct. 8 Nobody Loves Me Oct. -

The Legacy of Aaron Copland Reference Materials: General Performance Tips and Techniques

The Legacy of Aaron Copland Reference Materials: General Performance Tips and Techniques INTRODUCTION The United States Army Field Band and Soldiers’ Chorus have recently completed an ambitious recording project to celebrate the centenary of the “Dean of American Music,” Aaron Copland. With the 100th anniversary of his birth on November 14, 2000, ensembles throughout the nation and around the world are programming Copland’s music now more than ever. Our Legacy of Aaron Copland reference recordings and our online resources are intended to make his music more accessible to students and to assist conductors and educators in preparing for their own performances. During our recording sessions and the rehearsals that led up to them, the members of the Field Band learned much about Aaron Copland and his music. We have chosen to share some of those insights through An Educator’s Guide to the Music of Aaron Copland. JUDICIOUS EDITING One of the first lessons any performer learns is that the printed music is only a guide to the sounds which the composer wishes to have recreated. Students should realize that professional musicians use their experience to judiciously edit printed parts; this makes things easier to play, or better reflects the composer’s original intent. Seemingly small changes can often result in much cleaner execution of parts. They can also reduce the technical requirements for most of the sections, while maintaining the rhythmic pulse. Educators can greatly improve the performance of their ensembles by judicious editing, allowing their strongest players to carry the load, while easing the burden for less-experienced students. -

Shail, Robert, British Film Directors

BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS INTERNATIONAL FILM DIRECTOrs Series Editor: Robert Shail This series of reference guides covers the key film directors of a particular nation or continent. Each volume introduces the work of 100 contemporary and historically important figures, with entries arranged in alphabetical order as an A–Z. The Introduction to each volume sets out the existing context in relation to the study of the national cinema in question, and the place of the film director within the given production/cultural context. Each entry includes both a select bibliography and a complete filmography, and an index of film titles is provided for easy cross-referencing. BRITISH FILM DIRECTORS A CRITI Robert Shail British national cinema has produced an exceptional track record of innovative, ca creative and internationally recognised filmmakers, amongst them Alfred Hitchcock, Michael Powell and David Lean. This tradition continues today with L GUIDE the work of directors as diverse as Neil Jordan, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh and Ken Loach. This concise, authoritative volume analyses critically the work of 100 British directors, from the innovators of the silent period to contemporary auteurs. An introduction places the individual entries in context and examines the role and status of the director within British film production. Balancing academic rigour ROBE with accessibility, British Film Directors provides an indispensable reference source for film students at all levels, as well as for the general cinema enthusiast. R Key Features T SHAIL • A complete list of each director’s British feature films • Suggested further reading on each filmmaker • A comprehensive career overview, including biographical information and an assessment of the director’s current critical standing Robert Shail is a Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Wales Lampeter. -

1959 Jazz: a Historical Study and Analysis of Jazz and Its Artists and Recordings in 1959

GELB, GREGG, DMA. 1959 Jazz: A Historical Study and Analysis of Jazz and Its Artists and Recordings in 1959. (2008) Directed by Dr. John Salmon. 69 pp. Towards the end of the 1950s, about halfway through its nearly 100-year history, jazz evolution and innovation increased at a faster pace than ever before. By 1959, it was evident that two major innovative styles and many sub-styles of the major previous styles had recently emerged. Additionally, all earlier practices were in use, making a total of at least ten actively played styles in 1959. It would no longer be possible to denote a jazz era by saying one style dominated, such as it had during the 1930s’ Swing Era. This convergence of styles is fascinating, but, considering that many of the recordings of that year represent some of the best work of many of the most famous jazz artists of all time, it makes 1959 even more significant. There has been a marked decrease in the jazz industry and in stylistic evolution since 1959, which emphasizes 1959’s importance in jazz history. Many jazz listeners, including myself up until recently, have always thought the modal style, from the famous 1959 Miles Davis recording, Kind of Blue, dominated the late 1950s. However, a few of the other great and stylistically diverse recordings from 1959 were John Coltrane’s Giant Steps, Ornette Coleman’s The Shape of Jazz To Come, and Dave Brubeck’s Time Out, which included the very well- known jazz standard Take Five. My research has found many more 1959 recordings of equally unique artistic achievement. -

Tape ID Title Language System

Tape ID Title Language System 1375 10 English PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English NTSC 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian PAL 1078 18 Again English Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English pAL 1244 1941 English PAL 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English NTSC f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French PAL 1304 200 Cigarettes English Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English NTSC 2401 24 - Season 1, Vol 1 English PAL 2406 24 - Season 2, Part 1 English PAL 2407 24 - Season 2, Part 2 English PAL 2408 24 - Season 2, Part 3 English PAL 2409 24 - Season 2, Part 4 English PAL 2410 24 - Season 2, Part 5 English PAL 5675 24 Hour People English PAL 2402 24- Season 1, Part 2 English PAL 2403 24- Season 1, Part 3 English PAL 2404 24- Season 1, Part 4 English PAL 2405 24- Season 1, Part 5 English PAL 3287 28 Days Later English PAL 5731 29 Palms English PAL 5501 29th Street English pAL 3141 3000 Miles To Graceland English PAL 6234 3000 Miles to Graceland (NTSC) English NTSC f103 4 Adventures Of Reinette and Mirabelle (Subtitled) French PAL 0514s 4 Days English PAL 3421 4 Dogs Playing Poker English PAL 6607 4 Dogs Playing Poker (NTSC) English nTSC g033 4 Shorts By Werner Herzog (Subtitled) English PAL 0160 42nd Street English PAL 6306 4Th Floor (NTSC) English NTSC 3437 51st State English PAL 5310 54 English Pal 0058 55 Days At Peking English PAL 3052 6 Degrees Of Separation English PAL 6389 60s, The (NTSC) English NTSC 6555 61* (NTSC) English NTSC f126 7 Morts Sur Ordonnance (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 5623 8 1/2 Women English PAL 0253sn 8 1/2 Women (NTSC) English NTSC 1175 8 Heads In A Duffel Bag English pAL 5344 8 Mile English PAL 6088 8 Women (NTSC) (Subtitled) French NTSC 5041 84 Charing Cross Road English PAL 1129 9 To 5 English PAL f220 A Bout De Souffle (Subtitled) French PAL 0652s A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum English PAL f018 A Nous Deux (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 3676 A.W.O.L. -

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings TITLE PUBLICATION INFORMATION NUMBER DATE LANG 1-800-INDIA Mitra Films and Thirteen/WNET New York producer, Anna Cater director, Safina Uberoi. VD-1181 c2006. eng 1 giant leap Palm Pictures. VD-825 2001 und 1 on 1 V-5489 c2002. eng 3 films by Louis Malle Nouvelles Editions de Films written and directed by Louis Malle. VD-1340 2006 fre produced by Argosy Pictures Corporation, a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer picture [presented by] 3 godfathers John Ford and Merian C. Cooper produced by John Ford and Merian C. Cooper screenplay VD-1348 [2006] eng by Laurence Stallings and Frank S. Nugent directed by John Ford. Lions Gate Films, Inc. producer, Robert Altman writer, Robert Altman director, Robert 3 women VD-1333 [2004] eng Altman. Filmocom Productions with participation of the Russian Federation Ministry of Culture and financial support of the Hubert Balls Fund of the International Filmfestival Rotterdam 4 VD-1704 2006 rus produced by Yelena Yatsura concept and story by Vladimir Sorokin, Ilya Khrzhanovsky screenplay by Vladimir Sorokin directed by Ilya Khrzhanovsky. a film by Kartemquin Educational Films CPB producer/director, Maria Finitzo co- 5 girls V-5767 2001 eng producer/editor, David E. Simpson. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. ita Flaiano, Brunello Rondi. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. -

2019 Mandarins Brass Manual

“make your best sound” “always look your best” “it only counts on the move” MANDARINS METHODS & TECHNICAL MANUAL ‘\\\ 2019 MAKE YOUR BEST SOUND * ALWAYS LOOK YOUR BEST * IT ONLY COUNTS ON THE MOVE !1 MA19 – BRASS MANUAL –TABLE OF CONTENTS – IMPORTANT INFORMATION 3-4 REQUIRED REHEARSAL MATERIALS 5 THE BUCKET LIST 6 Brass Technique ◦ Air & Breathing Techniques 7-9 ◦ Embouchure Development 9-10 ◦ Bending Pitches 10 ◦ Foghorn Technique 11 ◦ Singing 11 ◦ Long Tones 12 ◦ Going to point (.1) 13 ▪ Long Tones | Going to .1 12-13 ▪ Flow Studies 13-16 ▪ Lip Slurs / Flexibility Exercises 17-20 ◦ Articulation & Style 21-26 ◦ Articulation Visualization 22 ▪ Tim’s ‘Ticulations 23 ▪ Articulation Exercises 23-26 ◦ Volume / Dynamics 27 ◦ Pitch & Intonation 27-29 ▪ Chord Adjustment Chart 29 ◦ Balance & Blend 30 ◦ Bopping 30 ◦ Pedal Tones 31 ◦ Stagger Breathing 31-33 ◦ Fingering Techniques 33-36 ▪ Clarke Studies 34-36 ▪ Tuning Tendency Chart(s) 37-38 MAKE YOUR BEST SOUND * ALWAYS LOOK YOUR BEST * IT ONLY COUNTS ON THE MOVE !2 INSTRUMENTATION The Mandarins brass section will consist of 79-80 members in: 24 Trumpets, 16 Mellophones, 8 Trombones, 16 Euphoniums and 15-16 Tubas. All of these spots are available each year. NO ONE, regardless of experience, is guaranteed a spot. Returning members must demonstrate a continued growth and development in order to be considered for membership. MANDARINS PLAY EXCLUSIVELY ON JUPITER INSTRUMENTS Trumpets: Jupiter XO Professional Trumpet 1602SR (Reverse Lead Pipe) Mellophone: Jupiter Mellophone JMP-1100MS Euphonium: Jupiter Marching Euphonium JEP-1100MS Tuba: Jupiter Marching Tuba JTU1100MS IN 2019 Mandarins will be adjusting instruments and the model numbers above could change. -

The Brass Family: Reading & Questions

The Brass Family: Reading & Questions Instructions: Read the information about the brass family, and then answer the following questions. The reading can be found below this document, or on the following website: https://www.ducksters.com/musicforkids/brass_instruments.php Please use complete sentences in your answers: *Note: If you want to submit through Google Classroom, the code is escoc7z 1. Describe how the vibration to make sound is created on a brass instrument: _____________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________ 2. Identify three types of music that use brass instruments: _____________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________ 3. Explain why a brass player would use a mute: _____________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________ 4. Explain why brass instruments are curved: _____________________________________________________________________________