A History of the Duke Department of Economics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

College and University Art Museums Reciprocal Program Participants

College and University Art Museums Reciprocal Program Participants ALABAMA Hammer Museum FLORIDA Abroms-Engel Institute for the Visual Arts University of California, Los Angeles Cornell Fine Arts Museum (AEIVA) hammer.ucla.edu Rollins College University of Alabama at Birmingham rollins.edu/cfam uab.edu/cas/aeiva University Art Museum California State University, Long Beach Harn Museum of Art Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art csulb.edu/org/uam University of Florida Auburn University harn.ufl.edu jcsm.auburn.edu COLORADO Center for Visual Art Leepa-Rattner Museum of Art ARIZONA Metropolitan State University of Denver St. Petersburg College Arizona State University Art Museum msudenver.edu/cva leeparattner.org Arizona State University asuartmuseum.asu.edu Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center Ruth Funk Center for Textile Arts at Colorado College Florida Institute of Technology Center for Creative Photography Colorado College textiles.fit.edu University of Arizona coloradocollege.edu/fac ccp.arizona.edu GEORGIA CONNECTICUT Bernard A. Zuckerman Museum of Art University of Arizona Museum of Art Fairfield University Museum of Art Kennesaw State University University of Arizona Fairfield University zuckerman.kennesaw.edu artmuseum.arizona.edu fairfield.edu/museum Georgia Museum of Art CALIFORNIA Housatonic Museum of Art University of Georgia Anderson Collection at Stanford University Housatonic Community College georgiamuseum.org Stanford University hcc.commnet.edu/artmuseum anderson.stanford.edu Michael C. Carlos Museum William Benton Museum -

John Harold Hughes, M.D., F.A.C.S Phone: 520-298-8511 Email: [email protected] Tucson, Arizona

John Harold Hughes, M.D., F.A.C.S Phone: 520-298-8511 Email: [email protected] Tucson, Arizona DISCIPLINE Surgery, Family & Community Medicine, Nanotechnology, Public Health EDUCATION Phillips Exeter Academy, Exeter, New Hampshire 1953 Cornell Medical College, New York, New York MD, Medicine, 1961 Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut BA, English, 1957 PROFESSIONAL LICENSURE/CERTIFICATIONS 1961-1962 Internship, St. Luke’s Hospital, New York, New York 1962-1966 Residency, St. Luke’s Hospital, New York, New York 1965 Board of Medical Examiners, Philadelphia Pennsylvania 1971 Fellowship, American College of Surgeons, Chicago, Illinois ACADEMIC/PROFESSIONAL WORK EXPERIENCE 1968-1968 Attending Surgeon, 93rd Evacuation Hospital, Long Binh, Republic of Viet Nam 1968-1968 Attending Surgeon, 18th Evacuation Hospital, Lai Khe, Republic of Viet Nam 1967-1967 Attending Surgeon, 12th Evacuation Hospital, Cu Chi, Republic of Viet Nam 1966-1968 Chief of General Surgery, Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indianapolis, Indiana 1969-1969 Commissioner of Health, Hardin County, Ohio 1970-1974 Commissioner of Health, Kenton-Hardin County General Health District 1972-1974 Medical Advances Institute, Columbus, Ohio Page 1 of 9 1972-1974 Medical Advances Institute Representative Councilor, Region 3 1973-1974 Acting Coroner, Hardin County, Ohio 1974-1977 Director of Surgical Clinics, Medical College of Ohio Hospital 1975-1977 Medical Director of Medical College of Ohio Clinics 1977-1980 Director of Emergency Services, University of Arizona Health Science Center 1986-1996 -

General Biographical Information

1 General Biographical Information STEPHEN JOHN (STEVE) BURGES Professor Emeritus of Civil and Environmental Engineering University of Washington Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering 164 Wilcox Hall, Box 352700 Seattle, Washington 98195-2700 (206) 543-7135 [email protected] Supplemental Born: Newcastle, Australia, 1944 Married: Wife - Sylvia Ellen Burges Citizenship: United States of America (Naturalized) Retired: June 2010 Biographies Outstanding Young Men of America (1979) American Men and Women of Science Who's Who in the West Who's Who in America Who's Who in Technology Who's Who of Emerging Leaders in America (2nd Edition) Who's Who in Science and Engineering Who's Who in the World (12th ed. & ff.) The International Directory of Distinguished Leadership Men of Achievement (International Man of the Year 1992-93) Personalities of America. Academic Background Ph.D. Civil Engineering Stanford University 1970 M.S. Civil Engineering Stanford University 1968 B.E. (Hons. I) Civil Engineering Newcastle, Australia 1967 B.Sc. Physics & Mathematics Newcastle, Australia 1967 Professional History Professor Emeritus, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, June 16, 2010-. Professor, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 1998 -2010. Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 1979- 1998. 2 Associate Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 1975-1979. Assistant Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 1970-1975. Research Assistant, Civil Engineering Department, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, 1967-1970. Assistant Construction Engineer, The Hunter District Water Board, Newcastle, Australia, 1966-1967. Refereed Journal Publications Burges, S.J. -

Murillo Campello

MurilloCampello December 2020 Samuel Curtis JohnsonGraduateSchoo lofManagementPho ne:(607) 255-1282 CornellUniversityE-mail:[email protected] 381SageHall Ithaca,NY14853-6201 CurrentAppointments 2011—:LewisH.DurlandProfessorofFinance,JohnsonSchool,CornellUniversity 2010—:ResearchAssociate,NationalBureau ofEconomicResearch(CorporateFinance) 2018—2020:AcademicDirector,FinancialManagementAssociation PastAppointmentsandVisits 2019,2020(SpringSemester):VisitingProfessorofFinance,UniversityNovadeLisboa 2017 (SpringSemester):VisitingProfessorofFinance,UniversityofCambridge 2014(March), 2016(FallSemester):Visitin gProfessorofFinance,ColumbiaUniversity 2009—2011, 2013—2015, 2019(May/June):VisitingProfessorofFinance,UniversityofAmsterdam 2013,2014(July):VisitingProfessorofFinance,ChineseUniversityofHongKong 2013,2015(September):VisitingScholar,FederalReserveBank ofNewYork 2016 (September):VisitingScholar,FederalReserveBankBoardofGovernors(D.C.) 2014,2015(July):VisitingProfessorofFinance,University ofQueensland 2015,2016, 2017,2018, 2019(November):Visitin gProfessorofFinance,University ofManchester 2006—2010:FacultyResearchFellow,NationalBureauofEconomicResearch(CorporateFinance) 2009—2011:Alan andJoyceBaltzProfessorofFinance,UniversityofIllinois 2008—2009: I.B.E.ProfessorofFinance,University of Illinois 2006—2008:AssociateProfessorofFinance,University of Illinois 2002—2006:AssistantProfessorofFinance,UniversityofIllinois 2001—2002:AssistantProfessorofFinance,MichiganStateUniversity 2000—2001:AssistantProfessorofFinance,ArizonaStateUniversity -

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

6Th Annual Duck Family Graduate Workshop on Environmental Politics and Governance

CENTER for ENVIRONMENTAL POLITICS 6th Annual Duck Family Graduate Workshop on Environmental Politics and Governance May 14-15, 2020 University of Washington A Word from the Center Director May 14, 2020 Dear Colleagues: Welcome to the 6th Annual Duck Family Graduate Workshop on Environmental Politics and Governance organized by the Center for Environmental Politics at University of Washington. We are delighted to host an impressive multi-disciplinary gathering of graduate students working on environmental policy, politics, and governance issues. Although this year we are organizing this workshop online, we hope you will find it exciting and rewarding. We also hope that you will get the opportunity to visit Seattle next year. The Center’s vision is to play a leadership role in producing and disseminating state of the art empirical research on environmental politics, policy, and governance at local, regional, national, and global levels. The Center’s 34 Faculty Associates are leaders in their fields, 24 Graduate Fellows are working on exciting doctoral projects, and 5 undergraduate fellows are engaged in independent research. Within the University of Washington, we facilitate faculty and graduate students to build connections, establish networks, and initiate truly multidisciplinary conversations about the governance, political, and institutional dimensions of environmental challenges. Externally, we are at the forefront of creating and nurturing a community of scholars committed to theoretically informed and empirically rigorous research on environmental politics, policy, and governance. This workshop reflects the vision of Gary and Susan Duck to create a vibrant intellectual community of emerging scholars studying environmental issues. Susan Duck is not with us anymore. -

History of Intercollegiate Athletics at the University of Arizona (1897-1948)

History of intercollegiate athletics at the University of Arizona (1897-1948) Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Svob, Robert Stanley, 1943- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 05/10/2021 20:06:50 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/553813 HISTORY OF INTERCOLLEGIATE ATHLETICS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA (1897-1948) by Robert Sv Svob A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of Education in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Graduate College, University of Arizona Approved: Date 80ITZJKTA KTAID-LLIOOHSTITI 10 Y5I0T2IH SIHT TA i m s i Y U . 10 VTIBHSVIHU ■ . '-d g'o y S «2 ihcocfoE aild- to %jIwoal edo- od- SQd-dlucfjLrs noid-;3oifKi to d-nen.t^qsG to eoigeA odd «iol cdxiome'iiirps'x odd to dcoisIIZtZijt XBJtdisq nl 8THA 10 HZTam anoslsA to idlcsovinU t&gsIIoO edcwaasD odd irZ Y) V 2X20 n'x i o ‘ic j o O'fi Ct £ 9 7 9 / / 9 & 0 t o 212500 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION............................... 1 Athletic .Plant ......................... 4 Purpose of Study ....................... 6 ... Limitations of Study ..... .... ; 6 Sources of Material ........ ...... 7 II. BASKETBALL, 1904-1949 ...... ........ 8 History ......... .............. 8 Year by Year Record ..................... 14 III. BASEBALL, 1901-1949 44 History................................ 44 Year by Year Record ................... -

Arizona Major Colleges and Universities 200 W

City of Phoenix Community and Economic Development Arizona Major Colleges and Universities 200 W. Washington St., 20th Floor | Phoenix, AZ 85003 Phoenix.gov/EconDev | 602-262-5040 IN PHOENIX LOCAL ENTREPRENEURIAL EFFORTS Arizona State • 53,286 at the Tempe campus • ASU is known for its approach to growing an entrepre- University • 11,420 student at the Downtown Phoenix Campus neurial enterprise within a public university system. • 4,929 at West (Glendale) • ASU was ranked #1 in the U.S. for Innovation by U.S. Total Enrollment: • 5,243 at Polytech (Mesa) News & World Report, ahead of Stanford and MIT. 119,951 • 45,073 at SkySong (Scottsdale) • ASU has supported 300+ student, faculty, alumni and • The ASU Thunderbird School of Global Management is external startups over the past 10 years. set to open on the Dowtown Phoenix Campus Fall 2021. • ASU integrates Entrepreneurship into the fabric of the university with in and out of class opportunities. University of Arizona • University of Arizona main campus is located in Tucson, • The McGuire Entrepreneurship Program at the main with students at a Downtown Phoenix Campus as well. campus in Tucson is a globally recognized program Total Enrollment: • Downtown degree programs include Eller College open to UA undergraduate and graduate students. 45,918 Executive and Evening MBA, UA College of Medicine • University of Arizona’s undergraduate McGuire at Phoenix Biomedical Campus. Entrepreneurship Program is ranked No. 8 by U.S. News & • UA Cancer Center at Dignity Health St. Joseph’s opened Wolrd Report (2020). in Fall 2015. Northern Arizona • Northern Arizona University is partnering with the • Northern Arizona Center for Entrepreneurship and University University of Arizona to allow students to reap the Technology fosters business growth and economic benefits of the Phoenix Biomedical Campus (PBC), vitality. -

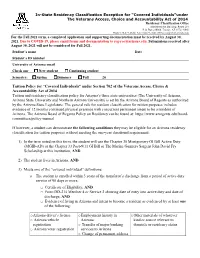

In-State Residency Classification Exception

In-State Residency Classification Exception for “Covered Individuals”under The Veterans Access, Choice and Accountability Act of 2014 Residency Classification Office Administration Building, Room 210 P.O. Box 210066, Tucson, AZ 85721-0066 Phone 520-621-3636 | Fax 520-621-3665 | [email protected] For the Fall 2021 term, a completed application and supporting documentation must be received by August 30, 2021. Due to COVID-19, please email forms and documentation to [email protected]. Submissions received after August 30, 2021 will not be considered for Fall 2021. Student’s name Date Student’s ID number University of Arizona email Check one □ New student □ Continuing student Semester: Spring Summer Fall 20 ___________ Tuition Policy for “Covered Individuals” under Section 702 of the Veterans Access, Choice & Accountability Act of 2014 Tuition and residency classification policy for Arizona’s three state universities (The University of Arizona, Arizona State University and Northern Arizona University) is set by the Arizona Board of Regents as authorized by the Arizona State Legislature. The general rule for resident classification for tuition purposes includes evidence of 12 months continued physical presence with concurrent permanent intent to be a resident of Arizona. The Arizona Board of Regents Policy on Residency can be found at: https://www.azregents.edu/board- committees/policy-manual If however, a student can demonstrate the following conditions they may be eligible for an Arizona residency classification for tuition purposes without meeting the one-year durational requirement: 1) In the term noted on this form, the student will use the Chapter 30 Montgomery GI Bill Active Duty (MGIB-AD) or the Chapter 33 Post-9/11 GI Bill or The Marine Gunnery Sargent John David Fry Scholarship at this institution, AND 2) The student lives in Arizona, AND 3) Meets one of the “covered individual” definitions: a. -

Furlough and Finance at Uarizona in the Wake of COVID-19

General Faculty Financial Advisory Committee Report (1) Furlough and Finance at UArizona in the Wake of COVID-19 Presented to the University of Arizona Executive Leadership Team Presented by the General Faculty Financial Advisory Committee (GFFAC) August 6, 2020 General Faculty Financial Advisory Committee Report (2) Table of Contents Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................................4 Committee Description and Charge...................................................................................................5 Creation of GFFAC.............................................................................................................................................. 5 Committee Duration ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Committee Members.......................................................................................................................................... 6 Committee Charge ............................................................................................................................................. 6 Report Goals ......................................................................................................................................................... 8 Research Options and Provide Recommendations .......................................................................... 8 Increase Understanding -

News from the University of Arizona Graduate Interdisciplinary Program

BIO5 Institute P.O. Box 210240 1657 E. Helen St. Graduate Interdisciplinary Program in Statistics Tucson, AZ 85721-0240 http://stat.arizona.edu News from The University of Arizona Graduate Interdisciplinary Program in STATISTICS Fall 2008 • The GIDP is pleased to announce that four new faculty members will join us in Fall 2008: Dr. Christopher S. Johnson of the University of Michigan will come to UA’s Department of Educational Psychology as an Assistant Professor. Dr. Johnson, who holds degrees in Educational Studies, Applied Statistics, and Mathematics, specializes in hierarchical regression/multilevel modeling, repeated measures analysis, and item response theory. Dr. Lingling An of Purdue University will come to UA’s Department of Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering as an Assistant Professor. Dr. An, whose doctoral degree is in Statistics, specializes in statistical genetics/genomics, bioinformatics, and computational biology. Dr. Chengcheng Hu of the Harvard School of Public Health will come to UA’s Division of Epidemiology & Biostatistics as an Assistant Professor. Dr. Hu has extensive research experience in both statistical methodology and collaborative clinical studies, and has also served as a Senior Statistician in the Center for Biostatistics in AIDS Research at Harvard. Dr. Scott R. Eliason from the University of Minnesota will come to UA’s Department of Sociology as an Associate Professor. Dr. Eliason specializes in categorical data analysis, correlated data modeling, and causal inference in the social sciences. We look forward to welcoming Drs. Johnson, An, Hu, and Eliason to campus this Fall! • The GIDP will matriculate its first class of graduate students this Fall! We are thrilled to welcome Ph.D. -

Anthony S. Gillies [email protected] 10.14.2020

Anthony S. Gillies www.thonygillies.org [email protected] 10.14.2020 Primary Appointments Professor of Philosphy 2015–present Rutgers University, New Brunswick Associate Professor of Philosphy 2009–2015 Rutgers University, New Brunswick Assistant Professor of Philosophy 2004–2009 University of Michigan Assistant Professor of Philosophy 2003–2004 Harvard University Assistant Professor of Philosophy 2001–2003 University of Texas at Austin Secondary Appointments Associate Faculty 2015–present Department of Linguistics Rutgers University, New Brunswick Executive Council 2016–present Center for Cognitive Science (RuCCS) Rutgers University, New Brunswick Affiliate Faculty 2011–present Interdisciplinary Center for Economic Science George Mason University Education Philosophy and Cognitive Science Ph.D., 1997–2001 University of Arizona Dissertation: Rational Belief Change Committee: John L. Pollock (chair), Shaughan Lavine, David Chalmers Philosophy and Political Science B.A., 1992–1996 Westminster College A. S. Gillies Magna Cum Laude Research Interests Philosophy of Language: Formal Semantics and Pragmatics; Epistemology: Belief Revision, Defeasible Reasoning; Philosophical Logic; Decision/Game Theory Editorial Positions Associate Editor, Semantics & Pragmatics 2012–present semprag.org Grants and Awards White Distinguished Visiting Professor Spring Quarter 2014 Department of Philosophy University of Chicago Context and Accommodation in the Semantics of Modal Constructions National Science Foundation 2006–2008 Division of Behavioral and Cognitive