1 COVER PAGE I. Project Name Planting for the Future: Financially

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bird Ecology, Conservation, and Community Responses

BIRD ECOLOGY, CONSERVATION, AND COMMUNITY RESPONSES TO LOGGING IN THE NORTHERN PERUVIAN AMAZON by NICO SUZANNE DAUPHINÉ (Under the Direction of Robert J. Cooper) ABSTRACT Understanding the responses of wildlife communities to logging and other human impacts in tropical forests is critical to the conservation of global biodiversity. I examined understory forest bird community responses to different intensities of non-mechanized commercial logging in two areas of the northern Peruvian Amazon: white-sand forest in the Allpahuayo-Mishana Reserve, and humid tropical forest in the Cordillera de Colán. I quantified vegetation structure using a modified circular plot method. I sampled birds using mist nets at a total of 21 lowland forest stands, comparing birds in logged forests 1, 5, and 9 years postharvest with those in unlogged forests using a sample effort of 4439 net-hours. I assumed not all species were detected and used sampling data to generate estimates of bird species richness and local extinction and turnover probabilities. During the course of fieldwork, I also made a preliminary inventory of birds in the northwest Cordillera de Colán and incidental observations of new nest and distributional records as well as threats and conservation measures for birds in the region. In both study areas, canopy cover was significantly higher in unlogged forest stands compared to logged forest stands. In Allpahuayo-Mishana, estimated bird species richness was highest in unlogged forest and lowest in forest regenerating 1-2 years post-logging. An estimated 24-80% of bird species in unlogged forest were absent from logged forest stands between 1 and 10 years postharvest. -

TOUR REPORT Southwestern Amazonia 2017 Final

For the first time on a Birdquest tour, the Holy Grail from the Brazilian Amazon, Rondonia Bushbird – male (Eduardo Patrial) BRAZIL’S SOUTHWESTERN AMAZONIA 7 / 11 - 24 JUNE 2017 LEADER: EDUARDO PATRIAL What an impressive and rewarding tour it was this inaugural Brazil’s Southwestern Amazonia. Sixteen days of fine Amazonian birding, exploring some of the most fascinating forests and campina habitats in three different Brazilian states: Rondonia, Amazonas and Acre. We recorded over five hundred species (536) with the exquisite taste of specialties from the Rondonia and Inambari endemism centres, respectively east bank and west bank of Rio Madeira. At least eight Birdquest lifer birds were acquired on this tour: the rare Rondonia Bushbird; Brazilian endemics White-breasted Antbird, Manicore Warbling Antbird, Aripuana Antwren and Chico’s Tyrannulet; also Buff-cheeked Tody-Flycatcher, Acre Tody-Tyrant and the amazing Rufous Twistwing. Our itinerary definitely put together one of the finest selections of Amazonian avifauna, though for a next trip there are probably few adjustments to be done. The pre-tour extension campsite brings you to very basic camping conditions, with company of some mosquitoes and relentless heat, but certainly a remarkable site for birding, the Igarapé São João really provided an amazing experience. All other sites 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Brazil’s Southwestern Amazonia 2017 www.birdquest-tours.com visited on main tour provided considerably easy and very good birding. From the rich east part of Rondonia, the fascinating savannas and endless forests around Humaitá in Amazonas, and finally the impressive bamboo forest at Rio Branco in Acre, this tour focused the endemics from both sides of the medium Rio Madeira. -

Universidade Federal Do Pará Instituto De Ciências Biológicas Embrapa Amazônia Oriental Programa De Pós-Graduação Em Ecologia

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO PARÁ INSTITUTO DE CIÊNCIAS BIOLÓGICAS EMBRAPA AMAZÔNIA ORIENTAL PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ECOLOGIA LUIZ HENRIQUE MEDEIROS BORGES O papel de mamíferos de médio e grande porte como modificadores do habitat na Amazônia ocidental Belém 2019 LUIZ HENRIQUE MEDEIROS BORGES O papel de mamíferos de médio e grande porte como modificadores do habitat na Amazônia ocidental Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia do convênio da Universidade Federal do Pará e Embrapa Amazônia Oriental, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Doutor em Ecologia. Área de concentração: Ecologia. Linha de pesquisa: Ecologia de Comunidades e Ecossistemas. Orientador(a): Prof. Dr. Carlos Augusto Peres da Silva. Co-orientadora: Profª Drª Ana Cristina Mendes-oliveira Belém 2019 LUIZ HENRIQUE MEDEIROS BORGES O papel de mamíferos terrestres como modificadores do habitat na Amazônia ocidental Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia do convênio da Universidade Federal do Pará e Embrapa Amazônia Oriental, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de Doutor em Ecologia pela Comissão Julgadora composta pelos membros: Drª Maria Aparecida Lopes Universidade Federal do Pará (Presidente) Drª Fernanda Michaslky Universidade Federal do Amapá Drº Arnaud Léonard Jean Dezbiez Escola Superior de Conservação Ambiental e Sustentabilidade (ESALQ) Drº Carlos Rodrigo Brocardo Instituto Neotropical: Pesquisa e Conservação Drº Armando Muniz Calouro Universidade Federal do Acre Drº Leonardo Carreira Trevelin Instituto tecnológico Vale Drª Marcela Guimarães Moreira Lima Universidade Federal do Pará Aprovado em: 13 de dezembro de 2019 Local de defesa: SAT 1 do Instituto de Ciências Biológicas da Universidade Federal do Pará. Dedico este trabalho a Maria Francimar e José Martins (meus pais), Rawanna Nascimento (minha esposa), minha base e minha fortaleza, e ao meu avô materno Manoel Rodrigues (Manoel Paca -In memorian), que tanto me incentivou indiretamente pelo seu modo de vida tradicional como seringueiro. -

A Comprehensive Species-Level Molecular Phylogeny of the New World

YMPEV 4758 No. of Pages 19, Model 5G 2 December 2013 Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution xxx (2013) xxx–xxx 1 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev 5 6 3 A comprehensive species-level molecular phylogeny of the New World 4 blackbirds (Icteridae) a,⇑ a a b c d 7 Q1 Alexis F.L.A. Powell , F. Keith Barker , Scott M. Lanyon , Kevin J. Burns , John Klicka , Irby J. Lovette 8 a Department of Ecology, Evolution and Behavior, and Bell Museum of Natural History, University of Minnesota, 100 Ecology Building, 1987 Upper Buford Circle, St. Paul, MN 9 55108, USA 10 b Department of Biology, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA 92182, USA 11 c Barrick Museum of Natural History, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV 89154, USA 12 d Fuller Evolutionary Biology Program, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University, 159 Sapsucker Woods Road, Ithaca, NY 14950, USA 1314 15 article info abstract 3117 18 Article history: The New World blackbirds (Icteridae) are among the best known songbirds, serving as a model clade in 32 19 Received 5 June 2013 comparative studies of morphological, ecological, and behavioral trait evolution. Despite wide interest in 33 20 Revised 11 November 2013 the group, as yet no analysis of blackbird relationships has achieved comprehensive species-level sam- 34 21 Accepted 18 November 2013 pling or found robust support for most intergeneric relationships. Using mitochondrial gene sequences 35 22 Available online xxxx from all 108 currently recognized species and six additional distinct lineages, together with strategic 36 sampling of four nuclear loci and whole mitochondrial genomes, we were able to resolve most relation- 37 23 Keywords: ships with high confidence. -

BIOLOGICAL INVENTORIES REPORTS ARE PUBLISHED BY: Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation./This Publication Has Been Funded in Part by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation

biological rapid inventories 11 Perú:Yavarí Nigel Pitman, Corine Vriesendorp, Debra Moskovits, editores/editors Noviembre/November 2003 Instituciones Participantes/Participating Institutions: The Field Museum Centro de Conservación, Investigación y Manejo de Áreas Naturales (CIMA–Cordillera Azul) Wildlife Conservation Society–Peru Durrell Institute of Conservation and Ecology Rainforest Conservation Fund Museo de Historia Natural de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos LOS INVENTARIOS BIOLÓGICOS RÁPIDOS SON PUBLICADOS POR / Esta publicación ha sido financiada en parte por la RAPID BIOLOGICAL INVENTORIES REPORTS ARE PUBLISHED BY: Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation./This publication has been funded in part by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. THE FIELD MUSEUM Environmental and Conservation Programs Cita Sugerida/Suggested Citation: Pitman, N., C. Vriesendorp, 1400 South Lake Shore Drive D. Moskovits (eds.). 2003. Perú: Yavarí. Rapid Biological Chicago, Illinois 60605-2496 USA Inventories Report 11. Chicago,IL: The Field Museum. T 312.665.7430, F 312.665.7433 Créditos fotográficos/Photography credits: www.fieldmuseum.org Carátula/Cover: El sapo Hyla granosa, colectado en la localidad de Quebrada Curacinha. Foto de Heinz Plenge./ Editores /Editors: Nigel Pitman, Corine Vriesendorp, The frog Hyla granosa, collected at the Quebrada Curacinha site. Debra Moskovits Photo by Heinz Plenge. Diseño/Design: Costello Communications, Chicago Carátula interior/Inner-cover: Río Yavarí. Foto de/Photo by Mapas/ Maps: Willy Llactayo, Richard Bodmer Heinz Plenge. Traducciones/Translations: EcoNews Peru, Hilary del Campo, Interior/Interior pages: Figs.1, 8 (mono/monkey) M. Bowler; Alvaro del Campo, Nigel Pitman, Tyana Wachter, Guillermo Knell Fig. 6B, H. Burn, Princeton University Press; Figs. 2F, 6A, 9C, 9E, 9H, A. -

Brazil: Remote Southern Amazonia Campos Amazônicos Np & Acre

BRAZIL: REMOTE SOUTHERN AMAZONIA CAMPOS AMAZÔNICOS NP & ACRE 7 – 19 July 2015 White-breasted Antbird (Rhegmatorhina hoffmannsi), Tabajara, Rondônia © Bradley Davis trip report by Bradley Davis ([email protected] / www.birdingmatogrosso.com) photographs by Bradley Davis and Bruno Rennó Introduction: This trip had been in the making since the autumn of 2013. Duncan, an avowed antbird fanatic, contacted me after having come to the conclusion that he could no longer ignore the Rio Roosevelt given the recent batch of antbird splits and new taxa coming from the Madeira – Tapajós interfluvium. We had touched on the subject during his previous trips in Brazil, having also toyed with the idea of including an expedition-style extension to search for Brazil's biggest mega when it comes to antbirds – the Rondônia Bushbird. After some back and forth in the first two months of the following year, an e-mail came through from Duncan which ended thusly: “statement of the bleedin’ obvious: I would SERIOUSLY like to see the Bushbird.” At which point the game was on, so to speak. We began to organize an itinerary for the Rio Roosevelt with a dedicated expedition for Rondonia Bushbird. By mid-year things were coming together for a September trip, but in August we were de-railed by a minor health problem and two participants being forced to back out at the last minute. With a bushbird in the balance, we weren't about to call the whole thing off, and thus a new itinerary sans Roosevelt was hatched for 2015, an itinerary which called for about a week in the Tabajara area on the southern border of the Campos Amazônicos National Park, followed by a few days on the west bank of the rio Madeira to go for a couple of Duncan's targets in that area. -

List of the Birds of Peru Lista De Las Aves Del Perú

LIST OF THE BIRDS OF PERU LISTA DE LAS AVES DEL PERÚ By/por MANUEL A. -

Neotropical News Neotropical News

COTINGA 1 Neotropical News Neotropical News Brazilian Merganser in Argentina: If the survey’s results reflect the true going, going … status of Mergus octosetaceus in Argentina then there is grave cause for concern — local An expedition (Pato Serrucho ’93) aimed extinction, as in neighbouring Paraguay, at discovering the current status of the seems inevitable. Brazilian Merganser Mergus octosetaceus in Misiones Province, northern Argentina, During the expedition a number of sub has just returned to the U.K. Mergus tropical forest sites were surveyed for birds octosetaceus is one of the world’s rarest — other threatened species recorded during species of wildfowl, with a population now this period included: Black-fronted Piping- estimated to be less than 250 individuals guan Pipile jacutinga, Vinaceous Amazon occurring in just three populations, one in Amazona vinacea, Helmeted Woodpecker northern Argentina, the other two in south- Dryocopus galeatus, White-bearded central Brazil. Antshrike Biata s nigropectus, and São Paulo Tyrannulet Phylloscartes paulistus. Three conservation biologists from the U.K. and three South American counter PHIL BENSTEAD parts surveyed c.450 km of white-water riv Beaver House, Norwich Road, Reepham, ers and streams using an inflatable boat. Norwich, NR10 4JN, U.K. Despite exhaustive searching only one bird was located in an area peripheral to the species’s historical stronghold. Former core Black-breasted Puffleg found: extant areas (and incidently those with the most but seriously threatened. protection) for this species appear to have been adversely affected by the the Urugua- The Black-breasted Puffleg Eriocnemis í dam, which in 1989 flooded c.80 km of the nigrivestis has been recorded from just two Río Urugua-í. -

Panorama Regional Y Descripción De Los Sitios

rapid inventories 29 RAPID BIOLOGICAL and SOCIAL INVENTORIES A FIELD MUSEUM PUBLICATION rapid inventories 29 rapid biological and social inventories rapid biological and social inventories 30 Colombia: Bajo Caguán-Caquetá Colombia: Bajo Caquán-Caquetá Instituciones participantes/Participating Institutions Field Museum Fundación para la Conservación y Desarrollo Sostenible (FCDS) Gobernación de Caquetá Corporación para el Desarrollo Sostenible del Sur de la Amazonia (CORPOAMAZONIA) Amazon Conservation Team-Colombia Parques Nacionales Naturales de Colombia ACAICONUCACHA ASCAINCA The Nature Conservancy-Colombia Proyecto Corazón de la Amazonia (GEF) Universidad de la Amazonia Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Universidad Nacional de Colombia Wildlife Conservation Society World Wildlife Fund-Colombia Esta publicación ha sido financiada en parte por el apoyo generoso de un donante anónimo, Bobolink Foundation, Hamill Family Foundation, Connie y Dennis Keller, Gordon and Betty Moore Inventories and Social Biological Rapid Foundation y el Field Museum./This publication has been funded in part by the generous support of an anonymous donor, Bobolink Foundation, Hamill Family Foundation, Connie and Dennis Keller, Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, and the Field Museum. Field Museum Keller Science Action Center Science and Education 1400 South Lake Shore Drive Chicago, Illinois 60605-2496, USA T 312.665.7430 F 312.665.7433 www.fieldmuseum.org THE FIELD MUSEUM THE FIELD ISBN 978-0-9828419-8-3 90000> 9 780982 841983 INFORME/REPORT NO. 30 Colombia: Bajo Caguán-Caquetá Nigel Pitman, Alejandra Salazar Molano, Felipe Samper Samper, Corine Vriesendorp, Adriana Vásquez Cerón, Álvaro del Campo, Theresa L. Miller, Elio Antonio Matapi Yucuna, Michelle E. Thompson, Lesley de Souza, Diana Alvira Reyes, Ana Lemos, Douglas F. -

The Envira Amazonia Project a Tropical Forest Conservation Project in Acre, Brazil

The Envira Amazonia Project A Tropical Forest Conservation Project in Acre, Brazil Prepared by Brian McFarland from: 853 Main Street East Aurora, New York - 14052 (240) 247-0630 With significant contributions from: James Eaton, TerraCarbon JR Agropecuária e Empreendimentos EIRELI Pedro Freitas, Carbon Securities Ayri Rando, Independent Community Specialist A Climate, Community and Biodiversity Standard Project Implementation Report TABLE OF CONTENTS COVER PAGE .................................................................................................................... Page 4 INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………..……………. Page 5 GENERAL SECTION G1. Project Goals, Design and Long-Term Viability …………………………….………. Page 6 A. Project Overview 1. Project Proponents 2. Project’s Climate, Community and Biodiversity Objectives 3. Project Location and Parameters B. Project Design and Boundaries 4. Project Area and Project Zone 5. Stakeholder Identification and Analysis 6. Communities, Community Groups and Other Stakeholders 7. Map Identifying Locations of Communities and Project 8. Project Activities, Outputs, Outcomes and Impacts 9. Project Start Date, Lifetime and GHG Accounting Period C. Risk Management and Long-Term Viability 10. Natural and Human-Induced Risks 11. Enhance Benefits Beyond Project Lifetime 12. Financial Mechanisms Adopted G2. Without-Project Land Use Scenario and Additionality ………………..…………….. Page 52 1. Most Likely Land-Use Scenario 2. Additionality of Project Benefits G3. Stakeholder Engagement ……………………………………………………………. Page 57 A. Access to Information 1. Accessibility of Full Project Documentation 2. Information on Costs, Risks and Benefits 3. Community Explanation of Validation and Verification Process B. Consultation 4. Community Influence on Project Design 5. Consultations Directly with Communities C. Participation in Decision-Making and Implementation 6. Measures to Enable Effective Participation D. Anti-Discrimination 7. Measures to Ensure No Discrimination E. Feedback and Grievance Redress Procedure 8. -

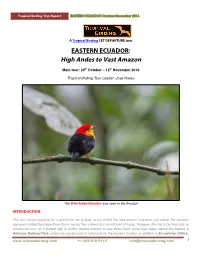

High Andes to Vast Amazon

Tropical Birding Trip Report EASTERN ECUADOR October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN ECUADOR: High Andes to Vast Amazon Main tour: 29th October – 12th November 2016 Tropical Birding Tour Leader: Jose Illanes This Wire-tailed Manakin was seen in the Amazon INTRODUCTION: This was always going to be a special for me to lead, as we visited the area where I was born and raised, the Amazon, and even visited the lodge there that is run by the community I am still part of today. However, this trip is far from only an Amazonian tour, as it started high in Andes (before making its way down there some days later), above the treeline at Antisana National Park, where we saw Ecuador’s national bird, the Andean Condor, in addition to Ecuadorian Hillstar, 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report EASTERN ECUADOR October-November 2016 Carunculated Caracara, Black-faced Ibis, Silvery Grebe, and Giant Hummingbird. Staying high up in the paramo grasslands that dominate above the treeline, we visited the Papallacta area, which led us to different high elevation species, like Giant Conebill, Tawny Antpitta, Many-striped Canastero, Blue-mantled Thornbill, Viridian Metaltail, Scarlet-bellied Mountain-Tanager, and Andean Tit-Spinetail. Our lodging area, Guango, was also productive, with White-capped Dipper, Torrent Duck, Buff-breasted Mountain Tanager, Slaty Brushfinch, Chestnut-crowned Antpitta, as well as hummingbirds like, Long-tailed Sylph, Tourmaline Sunangel, Glowing Puffleg, and the odd- looking Sword-billed Hummingbird. Having covered these high elevation, temperate sites, we then drove to another lodge (San Isidro) downslope in subtropical forest lower down. -

Neotropical Notebooks Please Include During a Visit on 9 April 1994 (Pyle Et Al

COTINGA 1 Neotropical Notebook Neotropical Notebook These recent reports generally refer to new or Chiriqui, during fieldwork between 1987 and 1991, second country records, rediscoveries, notable representing a disjunct population from that of Mexico range extensions, and new localities for threat to north-western Costa Rica (Olson 1993). Red- ened or poorly known species. These have been throated Caracara Daptrius americanus has been collated from a variety of published and unpub rediscovered in western Panama, with several seen and lished sources, and therefore some records will be heard on 26 August 1993 around the indian village of unconfirmed. We urge that, if they have not al Teribe (Toucan 19[9]: 5). ready done so, contributors provide full details to the relevant national organisations. COLOMBIA Recent expeditions and increasing interest in this coun BELIZE try has produced a wealth of new information, including There are five new records for the country as follows: a 12 new country records. A Cambridge–RHBNC expedi light phase Pomarine Jaeger Stercorarius pomarinus tion to Serranía de Naquén, Amazonas, in July–August seen by the fisheries pier, Belize City, 1 May 1992; 1992 found 4 new country records as follows: Rusty several Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor Tinamou Crypturellus brevirostris observed at an ant- seen at Cox Lagoon in November 1986, up to 20 at swarm at Caño Ima, 12 August; Brown-banded Crooked Tree in March 1988, and again on 3 May 1992; Puffbird Notharchus tricolor observed in riverside a Chuck-will’s Widow Caprimulgus carolinensis col trees between Mahimachi and Caño Colorado [no date]; lected at San Ignacio, Cayo District, 13 October 1991; and a male Guianan Gnatcatcher Polioptila guianensis Spectacled Foliage-gleaner Anabacerthia observed at close range in a mixed flock at Caño Rico, 2 variegaticeps recently recorded on an expedition to the August (Amazon 1992).