Wayne Merry: Finding the Essence of Adventure on El Capitan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior » , • National Park Service V National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination for individual properties and districts Sec instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" lor 'not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and area of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10- 900A). Use typewriter, word processor or computer to complete all items. 1. Name of Property____________________________________________________ historic name Camp 4 other name/site number Sunnyside Campground__________________________________________ 2. Location_______________________________________________________ street & number Northside Drive, Yosemite National Park |~1 not for publication city or town N/A [_xj vicinity state California code CA county Mariposa code 043 zip code 95389 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this Itjiomination _irquest for determination of eligibility meets the documentationsJand»ds-iJar -

![[PDF Download] Yosemite PDF Best Ebook](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4682/pdf-download-yosemite-pdf-best-ebook-144682.webp)

[PDF Download] Yosemite PDF Best Ebook

[PDF Download] Yosemite PDF Best Ebook Download Best Book Yosemite, Download Online Yosemite Book, Download pdf Yosemite, Download Yosemite E-Books, Download Yosemite Online Free, Free Download Yosemite Best Book, pdf Yosemite read online, Read Best Book Online Yosemite, Read Online Yosemite Best Book, Read Online Yosemite Book, Read Online Yosemite E-Books, Read Yosemite Online Free, Yosemite pdf read online Book details ● Author : Alexander Huber ● Pages : 176 pages ● Publisher : Menasha Ridge Press 2003-11- 10 ● Language : English ● ISBN-10 : 0897325575 ● ISBN-13 : 9780897325578 Book Synopsis Yosemite Valley is Mecca of the climbing sports. Such legends of climbing as John Salathé, Royal Robbins, and Warren Harding have immortalized their names in the granite of the valley. The giant walls of El Capitan and Half Dome haven t lost their magic attraction to this day. Climbers from all over the world pilgrimage to Yosemite year-round to do a Big Wall, to attempt Midnight Lightning, the most famous boulder in the world, and to experience the flair of the past in legendary Camp 4. From the surveys of geologists in the 1860 s to the "free speed" climbs of today, over 100 years of climbing history accompany a range of superb color landscape photos that echo the great traditions of the Ansel Adams and the Sierra Club large format books of the 1970s. Essays by well-known climbers Warren Harding, Royal Robbins, Jim Bridwell, Mark Chapman, Jerry Moffatt, John Long, Peter Croft, Lynn Hill, Thomas Huber, Dean Potter, and Leo Houlding illustrate the evolution in climbing equipment and varied techniques needed to ascend the rock peaks and amazing walls.. -

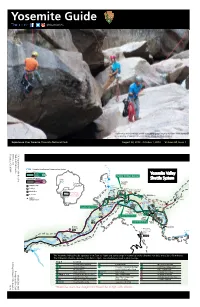

Yosemite Guide @Yosemitenps

Yosemite Guide @YosemiteNPS Yosemite's rockclimbing community go to great lengths to clean hard-to-reach areas during a Yosemite Facelift event. Photo by Kaya Lindsey Experience Your America Yosemite National Park August 28, 2019 - October 1, 2019 Volume 44, Issue 7 Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Summer-only Route: Upper Hetch Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Hetchy Shuttle Fall Yosemite Tuolumne Village Campground Meadows Lower Yosemite Parking The Ansel Fall Adams Yosemite l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area Picnic Area Valley l T Area in inset: al F e E1 t 5 Restroom Yosemite Valley i 4 m 9 The Ahwahnee Shuttle System se Yo Mirror Upper 10 3 Walk-In 6 2 Lake Campground seasonal 11 1 Wawona Yosemite North Camp 4 8 Half Dome Valley Housekeeping Pines E2 Lower 8836 ft 7 Chapel Camp Yosemite Falls Parking Lodge Pines 2693 m Yosemite 18 19 Conservation 12 17 Heritage 20 14 Swinging Center (YCHC) Recreation Campground Bridge Rentals 13 15 Reservations Yosemite Village Parking Curry Upper Sentinel Village Pines Beach il Trailhead E6 a Curry Village Parking r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr op h Beach Lo or M E4 ey ses erce all only d Ri V ver E5 Nevada Fall To & Bridalveil Fall d oa R B a r n id wo a a lv W e i The Yosemite Valley Shuttle operates from 7am to 10pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

Yosemite Guide Yosemite Guide July 22, 2020 - August 25, 2020 @Yosemitenps

Yosemite Guide Yosemite Guide July 22, 2020 - August 25, 2020 @YosemiteNPS UPDATE Due to the ongoing impact of COVID-19, visitor services and access may be affected. Check local resources and area signage in light of changing public health requirements related to COVID-19. For details, visit www.nps.gov/ yose. We encourage you to follow CDC guidance to reduce the spread of COVID-19. • Practice social distancing by maintaining 6 feet of distance between you and others. • Wear a face covering when social distancing cannot be maintained. • Wash your hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds. • Cover your mouth and nose when you cough or sneeze. • Most importantly, stay home if you feel sick. • Avoid touching your eyes, nose, and mouth. Maggie Howard sits among her baskets and basket materials in a Yosemite meadow. Learn about her legacy and the legacies of other women in Yosemite on page 10. Image by NPS Experience Your America Yosemite National Park Yosemite Guide July 22, 2020 - August 25, 2020 Experience Your America Yosemite National Park Yosemite Guide July 22, 2020 - August 25, 2020 Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System Year-round Route: Yosemite Valley Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Upper Map Campground Yosemite Fall Yosemite Parking Hetch Village Hetchy Lower Picnic Area Yosemite Tuolumne The Ansel Fall Adams l Medical Church Bowl Restroom Meadows i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area l T al F Walk-In e t i Campground m Yosemite e The Ahwahnee os Mirror Valley r Y Area in inset: Uppe 3 Lake Yosemite Valley seasonal -

The Electric Climber

Winter 1991 A Journal for Volume 53 Members of the Number 1 Yosemite Association Finding One's Way in the Age of Motorized Bolting The Electric Climber Hannah Gosnell When George Anderson made phone calls from people con- the first ascent of Half Dome in cerned about the number of bolts 1875 by engineering a bolt ladder put in Yosemite's walls by rock of sorts up the eastern flank of climbers today. the monolith, no one spoke out Why this new interest in boltsz against his impact on the re- It's because modern technology source. Nor did many object to (the cordless drill) is being utilized the Sierra Club 's 1919 attempt to to accomplish very quickly what make the peak more accessible to traditionally has been very slow non-climber tourists by putting and demanding work . That has in an elaborate system of expan- resulted in more holes and more sion bolts and cables to use as bolts in Yosemite granite. handrails . But in the past month, Rudolph attributes the recent Yosemite Search and Rescue deluge of concerned letters and Office Bob Howard and Chief phone calls about bolting to in- Ranger Roger Rudolph have been creased media coverage in the "swamped " with letters and last few months . "People think PAGE TWO YOSEMITE ASSOCIATION ,WINTER 1991 In an attempt to prove that climbing big walls did not necessarily require the use ofhundreds of bolts, Royal Robbins, Chuck Pratt and Tom Frost climbed the southwest face of El Capitan using only 13 bolts. the walls of Yosemite are going to of the Valley, including El Capitan, ing section of the Sierra Club the monolith). -

A Hitchhiker's Guide to Yosemite

DENNIS GRAY A Hitchhiker's Guide to Yosemite Senor, senor, do you know where we're headin? Lincoln County Road or Armageddon? Robert Zimmerman. hen I ftrst started to climb in 1947 (at the age of 11) petrol was W rationed and there were just a few vehicles on the roads. Getting from the Inner City, where my friends and I lived, to the outcrops of West Yorkshire and the Peak District took up a lot of our free time; until one day one of the climbers we met on these restricted travels introduced us to the noble art of hitchhiking. And voila! From then on the Lake District, Snowdonia and even a distant destination like the Isle of Skye fell within our compass. For about five years we travelled extensively by this method and came to admire its outstanding practitioners as much as the leading cragsmen of the day. Records were set for the fastest hitch from Leeds to Langdale, Bradford to Ogwen, Manchester to Glencoe. To the uninitiated hitching is just hitching. It appears that all you have to do is stick out your thumb. But nothing could be further from the truth. It demands technique, style, tactics, plus cunning territorial positioning. I believe the best hitchhikers to be master craftsmen. The few vehicles that were then on the roads, if they had any room, would usually stop and squeeze you in. Neville Drasdo was on one occasion given a lift near to Settle by two old farm ladies delivering eggs. Driving along, their vehicle unfortunately became unbalanced by his huge rucksack and manly physique and turned over at a sharp Z bend, ending upside down balanced on its roof. -

Rock Climbing Through the Ages

Rock Climbing through the Ages Michael Firmin UDLS: Feb 28, 2014 19th Century: The Alpine Shepherd 1854-1865: The Golden Age of Alpinism Matterhorn: Pennine Alps First Ascent: Edward Whymper (1865) Wetterhorn: Swiss Alps First Ascent: Alfred Willis (1854) First Ascents of the Golden Age ● 1854 Königspitze, Monte Rosa (Ostspitze), Strahlhorn ● 1855 Mont Blanc du Tacul, Monte Rosa (Westspitze), Weissmies ● 1856 Aiguille du Midi, Allalinhorn, Lagginhorn ● 1857 Mönch, Monte Pelmo ● 1858 Dom, Eiger, Nadelhorn, Piz Morteratsch, Wildstrubel ● 1859 Aletschhorn, Bietschhorn, Grand Combin, Grivola, Rimpfischhorn, Monte Leone ● 1860 Alphubel, Blüemlisalphorn, Civetta, Gran Paradiso, Grande Casse ● 1861 Castor, Fluchthorn, Lyskamm, Mont Pourri, Monte Viso, Schreckhorn, Weisshorn, Weißkugel ● 1862 Dent Blanche, Dent Parrachée, Doldenhorn, Gross Fiescherhorn, Monte Disgrazia, Täschhorn, Zuckerhütl ● 1863 Bifertenstock, Dent d'Hérens, Parrotspitze, Piz Zupò, Tofane ● 1864 Adamello, Aiguille d'Argentière, Aiguille de Tré la Tête, Antelao, Balmhorn, Barre des Écrins, Dammastock, Gross Wannenhorn, Marmolata, Mont Dolent, Pollux, Presanella, Zinalrothorn ● 1865 Aiguille Verte, Grand Cornier, La Ruinette, Matterhorn, Ober Gabelhorn, Piz Buin, Piz Roseg 1869: George Anderson’s Ascent of Half Dome Half Dome, Yosemite National Park 1886: W.P. Haskett Smith ascends the Napes Needle ● Introduces the English to rock climbing as a sport Napes Needle, Great Gable English Lake District 1892: Oscar Eckenstein ● Balance in Rock Climbing ● Bouldering Competitions Early -

Downward Bound: a Mad Guide to Rock Climbing, by Warren “Batso Harding, with Illustrations by Beryl “Beasto” Knath

Downward Bound: A Mad Guide to Rock Climbing, by Warren “Batso Harding, with illustrations by Beryl “Beasto” Knath. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1975. 204 pages, numerous photos and draw ings. Price $7.95. Climbing autobiographies have never become popular in American climb ing, probably due to the lack of audience. The scene has never had a public following as in such urban cultures, as France, which has produced many fine mountain memoirs, or Britain, which has also had a goodly number. One event in American climbing certainly did catch the public s fancy: Warren Harding’s climb of the Wall of Early Morning Light. Whether this was attention long overdue, a fluke or as Warren says, “Merely the result of a slack period in the overall news scene,” it gen erated a lot of public interest, gave Warren his long overdue fame— though not fortune—(he mock-laments that his first ascent of the Nose twelve years before was eclipsed in the news by the death of the Pope), created widespread fear and loathing in the climbing community, and eventually resulted in this book. Into this literary void steps the modest Batso, at times unsure for whom he is writing. The climbing community has read his trenchant pieces of satire—directed as much at himself as at others and loved him for it. Some of this new wit is obviously for them, but the book is basi cally for wider audiences. It starts with a lengthy discourse on the con duct of climbing, with answers to the question of “How does the rope get up there?” works into climbing “Philo-pharcy” and Warren’s life as a rock climber, and climaxes with “the big motha climb” itself. -

Critical Acclaim Greets a Night on the Ground, a Day in the Open

Critical Acclaim greets A Night on the Ground, A Day in the Open “An unqualified success, a memoir that's both excellent history and perhaps the most compelling portrait ever assembled of the American climbing spirit in the last 25 years. …The essays here deftly capture glimpses of a golden age, and the best have the lapidary quality of a fine poem—concentrated and dazzling.” — Rock & Ice magazine “It was by the campfire that the beauty of Robinson's words hit home. He welcomes the reader into his world and shares it with fine prose and Haiku images. He doesn't reach to tell a story, it comes naturally from his heart, in an unstrained, mystical way. I thank him for capturing that wonderful old mountain life feeling.” — Bob Woodward, co-founder of SNEWS, the insiders’ newsletter for the outdoor industry “Mountain climbing begets art. Like baseball and bullfighting, it has nurtured a whole body of literature. Robinson is one of climbing's leading practitioners. There is some jar- gon here...but Robinson's passion, humor and sometimes lyrical descriptive powers make these stories compelling to non-climbers. …The climbing life is as foreign to me as elephant taming. It was a treat to be shown through its inner and outer landscapes by an expert guide.” — Los Angeles Times “No one writes about the mountain experience quite like Doug Robinson does. Lyrical, vi- sionary (to use one of his favorite words), casual, poetic, elegant, unpretentious, mystical. Here, the quintessential Alpine vagabond sketches the delights of sublime indolence.” — Allen Steck, American Alpine Journal “[Doug] more than anyone else is carrying on Muir's great tradition of mountaineering writing.” — Yvon Chouinard, founder of Patagonia, Inc., climber, environmentalist, author “Doug Robinson is John Muir meets Jack Kerouac, a nineteenth century mountain man on a twentieth century journey, a seeker, a visionary...He is that rare treasure: a mountain man who can write, and he writes like a poet. -

North America Tom Connor

Triennial Report 1969-71 North America Tom Connor The last threeyears in NorthAmerica have seen significant new mountaineering activity in all the major climbing areas, and also extensions into new regions, such as some of the lesser-known areas of the Canadian Rockies and the Coastal Ranges. Perhaps the outstanding development has been the consolida tion of achievements in Yosemite, with many new climbs being done, and ascents of some of the better known routes on El Capitan becoming almost everyday events. Although Yosemite has by no means yielded all its riches, its widespread exploitation has resulted in the investigation of the potential of adjacent, but less accessible, areas in the Sierra Nevada such as Hetch Hetchy, which present similar climbing problems. Also, climbing on the Squamish Chief north of Vancouver seems to have come of age, and perhaps its easy accessibility and well-tried routes will tempt climbers to look for possible new wall climbs in this area also. Besides being a home for local Canadian climbers, the Chief has also become a favourite spot for many climbers from south ofthe border, in spite ofthe substantial travelling involved. The developments of interests and techniques which have led to the establish ment of big wall climbing are now being followed at a much later stage by advances in the scope of ice-climbing in North America. Following particularly the pioneering efforts of Yvon Chouinard, there has been an exploration of new techniques and equipment, and some significant adaptations ofestablished European practices. Some notes about the principal climbs which have been made in North America in the period 1969-71 have been kindly provided by Chris Jones, and are reproduced below, with a few minor amplifications. -

Yosemite Guide Yosemite Guide Summer 2020 @Yosemitenps

Yosemite Guide Yosemite Guide Summer 2020 @YosemiteNPS UPDATE Due to the ongoing impact of COVID-19, visitor services and access may be affected. For the safety of other visitors and employees, please comply with social distancing protocol. Check local resources for service hours and trail/facility access. For details, visit www.nps.gov/yose. We encourage you to follow CDC guidance to reduce the spread of COVID-19. • Practice social distancing by maintaining 6 feet of distance between you and others. • Wear a face covering when social distancing cannot be maintained. • Wash your hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds. • Cover your mouth and nose when you cough or sneeze. • Most importantly, stay home if you feel sick. • Avoid touching your eyes, nose, and mouth. Ansel Adams photographing Yosemite from the top of his car. Cedric Wright, Ansel Adams: Photographing in Yosemite, 1942, gelatin-silver print, Collection Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona, © 1942 Cedric Wright Experience Your America Yosemite National Park Yosemite Guide Summer 2020 Experience Your America Yosemite National Park Yosemite Guide Summer 2020 Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System Year-round Route: Yosemite Valley Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Upper Map Campground Yosemite Fall Yosemite Parking Hetch Village Hetchy Lower Picnic Area Yosemite Tuolumne The Ansel Fall Adams l Medical Church Bowl Restroom Meadows i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area l T al F Walk-In e t i Campground m Yosemite e The Ahwahnee os Mirror -

Warren Harding Semper Farcissimus June 18, 1924 - February 27, 2002

Warren Harding Semper Farcissimus June 18, 1924 - February 27, 2002 “Warren Harding? Well, what can I say?” That’s exactly how Warren would have started his own obituary. His usual demeanor was self-deprecating: To the question, “Are you the famous Warren Harding?,” he would retort, “Well, I used to be.” He believed that people are never what they were. They all grow… older. Harding died at home in Anderson, California, well aware that the end was near. He had been in failing health for over three years and refused to exchange his lifestyle for an extended life span. He approached his end with the same wit that he exhibited throughout his life. From his bed, just days before he died, he quipped that he was definitely never going to buy any more 50,000-mile-warranty tires. Warren was introduced to climbing at the age of 27 in 1952 and within a year had found his niche in Yosemite Valley. Most of us remember Harding as the Yosemite pioneer -- the prime mover in the first ascent of El Capitan in 1958, via the Nose, a milestone that marked the first time a wall of such size and difficulty had been climbed anywhere in the world. His first ascents of El Cap, the East Buttress and North Buttress of Middle Cathedral Rock, the West Face of the Leaning Tower, the East Face of Washington Column (later freed as Astroman), the South Face of Mount Watkins, the Direct Route on the Lost Arrow, and the South Face of Half Dome spanned the next two decades.