Headings in the Books of the Eighth-Century Prophets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intermarriage in Judaism Rabbi David M

Intermarriage in Judaism Rabbi David M. Freidenreich Intermarriage in the Bible and Jewish History Abraham was now old, advanced in years, and the Lord had blessed Abraham in all things. And Abraham said to the senior servant of his household, who had charge of all that he owned, “Put your hand under my thigh and I will make you swear by the Lord, the God of heaven and the God of earth, that you will not take a wife for my son from the daughters of the Canaanites among whom I dwell, but will go to the land of my birth and get a wife for my son Isaac.” (Gen. 24:1–5) When Esau was forty years old, he took to wife Judith daughter of Beeri the Hittite, and Basemath daugh- ter of Elon the Hittite; and they were a source of bitterness to Isaac and Rebekah…. Rebekah said to Isaac, “I am disgusted with my life because of the Hittite women. If Jacob marries a Hittite woman like these, from among the native women, what good will life be to me?” So Isaac sent for Jacob and blessed him. He instructed him, saying, “You shall not take a wife from among the Canaanite women. Up, go to Paddan-ar- am, to the house of Bethuel, your mother’s father, and take a wife there from among the daughters of Laban, your mother’s brother.” (Gen. 26:34–35, 27:46–28:2) Discussion Question: Why is it so important to Abraham and Rebekah—and also to Hagar (Gen. -

Gleaners Bible Studies E5

Gleaners Bible Studies E5 MESSAGES FROM THE PROPHETS Study 1 Jeremiah - God is True Jeremiah chapter 1 while following his ordinary path of duty in Anathoth and Read completely changed his life. Notice verse 5 of chapter 1. Can you imagine the surprise of the prophet when God In our studies in the lives of the prophets we have told him that he was already known and marked out to be already noted at least two vital factors in their work. Each a prophet of the Lord. Jeremiah protests and hesitantly man differed in personality, background and approach. expressed his sense of inadequacy for such a task. But Recognising this, we have seen how God makes use of this does not alter God’s intention. The prophet had to learn the individuality of His servants, fitting into His plans the that God’s command was also God’s enabling. The WORD particular traits of their varying personalities. So we have must be spoken - the TRUE WORD of God. God was going thought of Isaiah the statesman, Amos, the herdsman and to send Jeremiah to His people with a vital message. This Hosea the family man. Our study in the prophets becomes message would “root out”, “pull down”, “destroy”, fascinating as we keep these facts in mind. “throw down”, “build and plant”. (verse 10) Although Jeremiah felt his own complete unworthiness for the task, When we look at the life of Jeremiah, we come to a different God would not take ‘no’ for an answer. The lesson is clear character again. -

The Minor Prophets Michael B

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville Faculty Books 6-26-2018 A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets Michael B. Shepherd Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Shepherd, Michael B., "A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The inorM Prophets" (2018). Faculty Books. 201. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/201 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Books by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The inorM Prophets Keywords Old Testament, prophets, preaching Disciplines Biblical Studies | Religion Publisher Kregel Publications Publisher's Note Taken from A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets © Copyright 2018 by Michael B. Shepherd. Published by Kregel Publications, Grand Rapids, MI. Used by permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. ISBN 9780825444593 This book is available at DigitalCommons@Cedarville: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/faculty_books/201 A COMMENTARY ON THE BOOK OF THE TWELVE KREGEL EXEGETICAL LIBRARY A COMMENTARY ON THE BOOK OF THE TWELVE The Minor Prophets MICHAEL B. SHEPHERD Kregel Academic A Commentary on the Book of the Twelve: The Minor Prophets © 2018 by Michael B. Shepherd Published by Kregel Publications, a division of Kregel Inc., 2450 Oak Industrial Dr. NE, Grand Rapids, MI 49505-6020. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a re- trieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, me- chanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise—without written permission of the publisher, except for brief quotations in printed reviews. -

The Minor Prophets

The Minor Prophets by Dan Melhus A Study of the Minor Prophets Table of Contents Table of Contents INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................................ 1 WHO ARE THE PROPHETS?................................................................................................................... 5 HOW CAN WE UNDERSTAND THE MESSAGE OF THE PROPHETS?.......................................... 7 OBADIAH..................................................................................................................................................... 9 BACKGROUND................................................................................................................................. 9 DATE............................................................................................................................................... 9 AUTHOR .......................................................................................................................................... 10 THEME ............................................................................................................................................ 12 OUTLINE ......................................................................................................................................... 13 QUESTIONS...................................................................................................................................... 15 LESSONS......................................................................................................................................... -

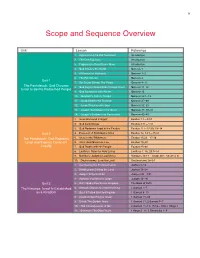

Scope and Sequence Overview

9 Scope and Sequence Overview Unit Lesson Reference 1. Approaching the Old Testament Introduction 2. The One Big Story Introduction 3. Preparing to Read God's Word Introduction 4. God Creates the World Genesis 1 5. A Mission for Humanity Genesis 1–2 6. The Fall into Sin Genesis 3 Unit 1 7. Sin Grows Worse: The Flood Genesis 4–11 The Pentateuch: God Chooses 8. God Begins Redemption through Israel Genesis 11–12 Israel to Be His Redeemed People 9. God Covenants with Abram Genesis 15 10. Abraham's Faith Is Tested Genesis 22:1–19 11. Jacob Inherits the Promise Genesis 27–28 12. Jacob Wrestles with God Genesis 32–33 13. Joseph: God Meant It for Good Genesis 37; 39–41 14. Joseph's Brothers Are Reconciled Genesis 42–45 1. Israel Enslaved in Egypt Exodus 1:1—2:10 2. God Calls Moses Exodus 2:11—4:31 3. God Redeems Israel in the Exodus Exodus 11:1–12:39; 13–14 Unit 2 4. Passover: A Redemption Meal Exodus 12; 14:1—15:21 The Pentateuch: God Redeems 5. Israel in the Wilderness Exodus 15:22—17:16 Israel and Expects Covenant 6. Sinai: God Gives His Law Exodus 19–20 Loyalty 7. God Dwells with His People Exodus 25–40 8. Leviticus: Rules for Holy Living Leviticus 1; 16; 23:9–14 9. Numbers: Judgment and Mercy Numbers 13:17—14:45; 20:1–13; 21:4–8 10. Deuteronomy: Love the Lord! Deuteronomy 28–34 1. Conquering the Promised Land Joshua 1–12 2. -

Ordinary Prophets, Extraordinary Lives Howard R

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Truth's Bright Embrace: Essays and Poems in Honor College of Christian Studies of Arthur O. Roberts 1996 Ordinary Prophets, Extraordinary Lives Howard R. Macy George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/truths_bright Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons Recommended Citation Macy, Howard R., "Ordinary Prophets, Extraordinary Lives" (1996). Truth's Bright Embrace: Essays and Poems in Honor of Arthur O. Roberts. Paper 3. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/truths_bright/3 This Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Christian Studies at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Truth's Bright Embrace: Essays and Poems in Honor of Arthur O. Roberts by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. Ordinary Prophets, Extraordinary Lives HOWARD R. MACY will propose in this essay that the lives of the prophets, or more pre cisely, the practical results of the spirituality of the prophets, can guide I our own living as followers of Christ. They can supply insights which can help interpret our experience, and they can hold out vistas of possibili tiesfor growth which we may not yet have realized. As I sometimes warn my students, I should caution that understanding the prophets may corrupt your life. Just about the time you've caught on to what the prophets are doing, you discover that they've caught you. Once you know what the prophets knew by heart, a revolution begins which can not fully be resisted or undone. -

Of Malachi Studies of the Old Testament's Ethical Dimensions

ABSTRACT The Moral World(s) of Malachi Studies of the Old Testament’s ethical dimensions have taken one of three approaches: descriptive, systematic, or formative. Descriptive approaches are concerned with the historical world, social context, and streams of tradition out of which OT texts developed and their diverse moral perspectives. Systematic approaches investigate principles and paradigms that encapsulate the unity of the OT and facilitate contemporary appropriation. Formative approaches embrace the diversity of the OT ethical witnesses and view texts as a means of shaping the moral imagination, fostering virtues, and forming character The major phase of this investigation pursues a descriptive analysis of the moral world of Malachi—an interesting case study because of its location near the end of the biblical history of Israel. A moral world analysis examines the moral materials within texts, symbols used to represent moral ideals, traditions that helped shape them, and the social world (political, economic, and physical) in which they are applied. This study contributes a development to this reading methodology through a categorical analysis of moral foundations, expectations, motives, and consequences. This moral world reading provides insight into questions such as what norms and traditions shaped the morals of Malachi’s community? What specific priorities, imperatives, and injunctions were deemed important? How did particular material, economic, and political interests shape moral decision-making? How did religious symbols bring together their view of the world and their social values? The moral world reading is facilitated by an exploration of Malachi’s social and symbolic worlds. Social science data and perspectives are brought together from an array of sources to present six important features of Malachi’s social world. -

Pdf Israelian Hebrew in the Book of Amos

ISRAELIAN HEBREW IN THE BOOK OF AMOS Gary A. Rendsburg 1.0. The Location of Tekoa The vast majority of scholars continue to identify the home vil- lage of the prophet Amos with Tekoa1 on the edge of the Judean wilderness—even though there is little or no evidence to support this assertion. A minority of scholars, the present writer included, identifies the home village of Amos with Tekoa in the Galilee— an assertion for which, as we shall see, there is considerable solid evidence. 1.1. Southern Tekoa The former village is known from several references in Chroni- cles, especially 2 Chron. 11.6, where it is mentioned, alongside Bethlehem, in a list of cities fortified by Rehoboam in Judah. See also 2 Chron. 20.20, with reference to the journey by Jehosha- to the wilderness of Tekoa’.2‘ לְמִדְב ַּ֣ר תְקֹ֑וע phat and his entourage The genealogical records in 1 Chron. 2.24 and 4.5, referencing a 1 More properly Teqoaʿ (or even Təqōaʿ), but I will continue to use the time-honoured English spelling of Tekoa. 2 See also the reference to the ‘wilderness of Tekoa’ in 1 Macc. 9.33. © 2021 Gary A. Rendsburg, CC BY 4.0 https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0250.23 718 New Perspectives in Biblical and Rabbinic Hebrew Judahite named Tekoa, may also encode the name of this village. The name of the site lives on in the name of the Arab village of Tuquʿ and the adjoining ruin of Khirbet Tequʿa, about 8 km south of Bethlehem.3 1.2. -

On the Qur'ān and the Theme of Jews As “Killers of the Prophets1

DOI: 10.11136/jqh.1210.02.02 ON THE QUR’ĀN AND THE THEME OF JEWS AS “KILLERS OF THE PROPHETS 1 Gabriel Said Reynolds* Abstract A prominent element of the Qur’ān’s material on the Jews is its report that the Israelites killed prophets sent to them. The Qur’an does not describe the killing of any particular prophet, nor does it attempt to prove in any other way that the Jews have killed the prophets. Instead the Qur’an seems to consider it common knowledge that the Jews have done so as it makes certain inter- religious arguments in this light. However, on the basis of the Hebrew Bible the prominence of this theme in the Qur’an hardly makes sense. None of the great prophets in the Hebrew Bible are killed by the Israelites. In the present paper I argue that this theme emerges from the para-biblical traditions which indeed describe how the Jews killed the prophets whom God sent to them. These traditions are found already in Jewish texts, and they lead Christian authors -- including New Testament authors – to connect the Jewish persecution of Christian believers with their earlier persecution of the prophets who predicted the coming of Christ. This connection is prominent in the anti- Jewish literature of the Syriac Christian authors. The manner in which the Qur’an employs the theme of Jews as killers of the prophets is closely related to that literature. Keywords: Qur’an, Jews, Christians, Prophets, Syriac, Midrash, Ephrem, Jacob of Serug. * University of Notre Dame, [email protected]. -

Zechariah's Word

Zechariah’s Word 1 In the eighth month, in the second year of Darius, the word of the LORD1 came to the prophet Zechariah, the son of Berechiah, son of Iddo, saying, 2 "The LORD was very angry with your fathers. 3 Therefore say to them, Thus declares the LORD of hosts: Return to me, says the LORD of hosts, and I will return to you, says the LORD of hosts. 4 Do not be like your fathers, to whom the former prophets cried out, 'Thus says the LORD of hosts, Return from your evil ways and from your evil deeds.' But they did not hear or pay attention to me, declares the LORD. 5 Your fathers, where are they? And the prophets, do they live forever? 6 But my words and my statutes, which I commanded my servants the prophets, did they not overtake your fathers? So they repented and said, 'As the LORD of hosts purposed to deal with us for our ways and deeds, so has he dealt with us.'" Zechariah 1:1-6 The Veil is Taken Off EACH WEEK IN OUR CHURCH’S WORSHIP SERVICE, we read a portion of God’s law, and then later we read from the gospel. Both wings of the Protestant Reformation (Lutheran and Reformed) taught that there are two basic “words” of Scripture. That is, all Scripture can be divided into two basic categories. These categories are law and gospel. These are not equivalent to OT (law) and NT (gospel), because there is gospel in the OT (Gen 3:15; etc.; cf. -

Lnformaîlon to USERS

lNFORMAîlON TO USERS This manuscript has been mpmûuœd from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly frm the ofigiinal or copy submitted. Thus, some Wsand dissertation copies are in typewriter fscs, wuhile athen may be fr#n any type of cornputer printer. Wqurîiiofthk n(noducbkn k deponâantupontheqwlityafthecopy submitteô. Brokm or indistinct cokred or poor quality iilustratiorrs and photographs, print bkdhrough, Mibstandatd margins, and impraper alignment can adversely affect reprioduction. In the unlikely event aiat aie author did riot send UMI a compîete rnariuscxipt and the- are missing pages, these wiH be noteâ. Also, if unauthorired copyright material had to be mmoved, a note Ml indiiethe deidon. Ovemire matsrials (0-g., maps, drawings. charts) are repFoduced by sectiming the original, beginning at trie u-r Mharid corner and uminuing frm left to right in equal wiai small overhps. Photographs induded in aie original manusaipt have beeri reproduœd xerogaphicslly in mis -y. Higher quality 6' x 9 blîdr and nitr'- photographie prïnts are avaibbk for any photogmphs or illusûaüons -ring in this wpy for an additional charge. Contact UMI diredly to order. Beil8 Haniiell lnfonnatian and Lemming 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Am,MI 481m1346 USA EXODUS 34:29-35: MOSES' C6HORNSnIN EARLY BIBLE TRANSLATIONS AND INTERPRETATIONS Bena Elisha Medjuck Department of Jewish Studies McGiiL University, Montréal, Québec, Canada March 1998 A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree ofMaster of Arts Q Bena Medjuck 1998 National Lirary Bibliothèque nationale 191 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibiiographic Services seMces bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. -

Hosea Traditional Author: Hosea, Son of Beeri. Approximate Time Of

Hosea Traditional Author: Hosea, son of Beeri. Approximate Time of Writing: 760-720 B.C. General Content: Historical Narrative and Prophecy. Hosea was the primary writing prophet of the Northern Kingdom, starting well before and continuing until after its fall. He ministered during the last forty or fifty years of the Northern Kingdom where there was no legitimate priesthood functioning. The existing priesthood in the north was mixed with idolatry and corrupting influences from its inception. (See 1 Kings 12:25-33 & 2 Kings 17) Prophetic ministry was the only true ministry the people of the Northern Kingdom received in those days. Even though this book is factually historical, most of the book of Hosea is written as an allegory of the Lord’s relationship with Israel. In the first chapter, Hosea is instructed to take a prostitute named Gomer for his wife. The book explains that Gomer is symbolic of unfaithful Israel, and faithful Hosea represents the Lord. The reader is made to understand that this is how the Lord sees His relationship with ancient Israel; with God steadfast in His committed love and Israel often running off to worship other gods, as a prostitute with other lovers. It also contains the redemptive promises of marriage from God to the Jewish people, recited daily by many observant Jews. Hosea reveals Israel as the OT Wife of God as a type and shadow of the NT Church as the Bride of Christ. Christians need to consider the message of Hosea and understand that, like the Jewish people before us, we often are unfaithful in our devotion toward Him, but He is always faithful toward us.