Life Writing Prize 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with William T. Wiley, 1997 October 8-November 20

Oral history interview with William T. Wiley, 1997 October 8-November 20 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview PAUL KARLSTROM: Smithsonian Institution, an interview with William T. Wiley, at his studio in Woodacre, California, north of San Francisco. The date is October 8, 1997. This is the first session in what I hope will be a somewhat extensive series. The interviewer for the archives is Paul Karlstrom. Okay, here we go, Bill. I've been looking forward to this interview for quite a long time, ever since we met back in, it was the mid-seventies, as a matter of fact. At that time, in fact, I visited right here in this studio. We talked about your papers and talked about sometime doing an interview, but for one reason or another, it didn't happen. Well, the advantage to that, as I mentioned earlier, is that a lot has transpired since then, which means we have a lot more to talk about. Anyway, we can't go backwards, and here we are. I wanted to start out by setting the stage for this interview. As I mentioned, Archive's [of American Art] interviews are comprehensive and tend to move along sort of biographical, chronological structure, at least it gives something to follow through. But what I would like to do first of all, just very briefly, is kind of set the stage, and by way of an observation that I would like to make, which is also, I think, a compliment. -

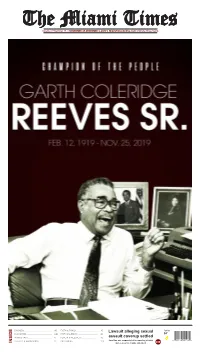

INSIDE and Coerced to Change Statement 10D Editorials Cartoons Opinions Letters

Volume 97 Number 15 | NOVEMBER 27-DECEMBER 3, 2019 | MiamiTimesOnline.com | Ninety-Three Cents BUSINESS ................................................. 8B FAITH & FAMILY ...................................... 7D Lawsuit alleging sexual Today CLASSIFIED ............................................. 11B FAITH CALENDAR ................................... 8D 84° IN GOOD TASTE ......................................... 1C HEALTH & WELLNESS ............................. 9D assault coverup settled LIFESTYLE HAPPENINGS ....................... 5C OBITUARIES ............................................. 12D Jane Doe was suspended after reporting attacks 8 90158 00100 0 INSIDE and coerced to change statement 10D Editorials Cartoons Opinions Letters VIEWPOINT BLACKS MUST CONTROL THEIR OWN DESTINY | NOVEMBER 27-DECEMBER 3, 2019 | MiamiTimesOnline.com MEMBER: National Newspaper Periodicals Postage Credo Of The Black Press Publisher Association paid at Miami, Florida Four Florida outrages: (ISSN 0739-0319) The Black Press believes that America MEMBER: The Newspaper POSTMASTER: Published Weekly at 900 NW 54th Street, can best lead the world from racial and Association of America Send address changes to Miami, Florida 33127-1818 national antagonism when it accords Subscription Rates: One Year THE MIAMI TIMES, The wealthy flourish, Post Office Box 270200 to every person, regardless of race, $65.00 – Two Year $120.00 P.O. Box 270200 Buena Vista Station, Miami, Florida 33127 creed or color, his or her human and Foreign $75.00 Buena Vista Station, Miami, FL Phone 305-694-6210 legal rights. Hating no person, fearing 7 percent sales tax for Florida residents 33127-0200 • 305-694-6210 the poor die H.E. SIGISMUND REEVES Founder, 1923-1968 no person, the Black Press strives to GARTH C. REEVES JR. Editor, 1972-1982 help every person in the firm belief that ith President Trump’s impeachment hearing domi- GARTH C. REEVES SR. -

Wonderful! 143: Rare, Exclusive Gak Published July 29Th, 2020 Listen on Themcelroy.Family

Wonderful! 143: Rare, Exclusive Gak Published July 29th, 2020 Listen on TheMcElroy.family [theme music plays] Rachel: I'm gonna get so sweaty in here. Griffin: Are you? Rachel: It is… hotototot. Griffin: Okay. Is this the show? Are we in it? Rachel: Hi, this is Rachel McElroy! Griffin: Hi, this is Griffin McElroy. Rachel: And this is Wonderful! Griffin: It‘s gettin‘ sweaaatyyy! Rachel: [laughs] Griffin: It‘s not—it doesn‘t feel that bad to me. Rachel: See, you're used to it. Griffin: Y'know what it was? Mm, I had my big fat gaming rig pumping out pixels and frames. Comin‘ at me hot and heavy. Master Chief was there. Just so fuckin‘—just poundin‘ out the bad guys, and it was getting hot and sweaty in here. So I apologize. Rachel: Griffin has a very sparse office that has 700 pieces of electronic equipment in it. Griffin: True. So then, one might actually argue it‘s not sparse at all. In fact, it is filled with electronic equipment. Yeah, that‘s true. I imagine if I get the PC running, I imagine if I get the 3D printer running, all at the same time, it‘s just gonna—it could be a sweat lodge. I could go on a real journey in here. But I don‘t think it‘s that bad, and we‘re only in here for a little bit, so let‘s… Rachel: And I will also say that a lot of these electronics help you make a better podcast, which… is a timely thing. -

Publication Management, Content Strategy & Execution Specialty Writing Production & Consulting

Content Strategy & Execution Content Strategy 843.513.7535 ~ [email protected] riverbendcustomcontent.com Professional Profile Respected leader of creative teams with proven ability to conceptualize and orchestrate communications campaigns that effectively build and reinforce brand. Collaborative team player adept at transforming complex ideas and subject matter into digestible information that connects, enlightens and engages target markets and segments. Select Professional Achievements Established and executed a content/thought leadership communications program to enhance the Elliott Davis brand and strengthen the firm’s position as a diversified business solutions provider offering a full spectrum of professional financial services and consulting. Content Strategy Created and directed the National Golf Course Owners Association’s first Comprehensive In conjunction with CMO and Content Strategy, a three-phase, multi-year plan that established the four pillars under marketing director, developed a which all NGCOA educational content was categorized and developed. comprehensive plan and editorial calendar to create, schedule and Spearheaded two complete repositionings of Golf Business magazine, re-establishing the deliver content and collateral for title as the golf industry’s preeminent business publication. all Elliott Davis business units. Garnered multiple awards for writing and publication excellence from the Society of National Association Publications, Turf & Ornamental Communications Association, International Network of Golf and Carolinas Golf Reporters Association. Areas of Specialty & Expertise Editorial, Creative & Publication Management, Content Strategy & Execution Specialty Writing Production & Consulting Experienced professional Award-winning writer whose Veteran, award-winning skilled in the development articles and columns have magazine editor with more and creation of content, appeared in numerous national, than two decades of experience educational curricula and regional and local publications. -

YCH Monograph TOTAL 140527 Ts

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transformation of The Musical: The Hybridization of Tradition and Contemporary A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirement for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Yu-Chun Hu 2014 Copyright by Yu-Chun Hu 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transformation of The Musical: The Hybridization of Tradition and Contemporary by Yu-Chun Hu Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Ian Krouse, Chair Music and vision are undoubtedly connected to each other despite opera and film. In opera, music is the primary element, supported by the set and costumes. The set and costumes provide a visual interpretation of the music. In film, music and sound play a supporting role. Music and sound create an ambiance in films that aid in telling the story. I consider the musical to be an equal and reciprocal balance of music and vision. More importantly, a successful musical is defined by its plot, music, and visual elements, and how well they are integrated. Observing the transformation of the musical and analyzing many different genres of concert music, I realize that each new concept of transformation always blends traditional and contemporary elements, no matter how advanced the concept is or was at the time. Through my analysis of three musicals, I shed more light on where this ii transformation may be heading and what tradition may be replaced by a new concept, and vice versa. My monograph will be accompanied by a musical work, in which my ultimate goal as a composer is to transform the musical in the same way. -

Wolf Brothers Country Heart Album Free Download

wolf brothers country heart album free download The Blues Brothers [Original Soundtrack] Comic actors John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd received a lot of flak for their Blues Brothers shtick -- mostly for the albums, not 1980's beloved classic film. But they should be given credit for exposing many people -- including this reviewer -- to the music of blues and R&B veterans. The Blues Brothers soundtrack was released on Atlantic Records. On the surface this doesn't seem unusual, since the Blues Brothers' Atlantic debut, Briefcase Full of Blues, was a number one album; but the movie was released by Universal, and its parent company, MCA, passed on the soundtrack. The rollicking remake of the Spencer Davis Group's "Gimme Some Lovin'" was a hit, featuring an arrangement notable for the horn section that replaces Steve Winwood's rumbling organ work. Ray Charles has a good time with "Shake a Tail Feather," and he's helped out by Jake and Elwood Blues (Belushi and Aykroyd, respectively). The cover of Solomon Burke's "Everybody Needs Somebody to Love" is a lot of fun, thanks to the great overall rhythm and Elwood's lightning-fast stage rap, while James Brown and the Reverend James Cleveland Choir provide a blast of gospel music on "Old Landmark." Aretha Franklin's "Think" is explosive, and Cab Calloway's "Minnie the Moocher" is slyly irresistible. Charles, Brown, Franklin, and Calloway all have small roles in the film, yet so does John Lee Hooker, but he's not represented here. Wolf brothers country heart album free download. Jimmie Rogers Blue Yodeler Jeannie Seeley Don't Touch Me. -

Score Alfred Music Publishing Co. Finn

Title: 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee, The - score Author: Finn, William Publisher: Alfred Music Publishing Co. 2006 Description: Score for the musical. Title: 42nd Street - vocal selections Author: Warren, Harry Dubin, Al Publisher: Warner Bros. Publications 1980 Description: Vocal selections from the musical. Contains: About a Quarter to Nine Dames Forty-Second Street Getting Out Of Town Go Into Your Dance The Gold Digger's Song (We're In The Money) I Know Now Lullaby of Broadway Shadow Waltz Shuffle Off To Buffalo There's a Sunny Side to Every Situation Young and Healthy You're Getting To Be a Habit With Me Title: 9 to 5 - vocal selections The musical Author: Parton, Dolly Publisher: Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation Description: Vocal selections from the musical. Contains: Nine to Five Around Here Here for You I Just Might Backwoods Barbie Heart to Hart Shine Like the Sun One of the Boys 5 to 9 Change It Let Love Grow Get Out and Stay Out Title: Addams Family - vocal selections, The Author: Lippa, Andrew Publisher: Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation 2010 Description: Vocal selections from the musical. includes: When You're an Addams Pulled One Normal Night Morticia What If Waiting Just Around the Corner The Moon and Me Happy / Sad Crazier than You Let's Not Talk About Anything Else but Love In the Arms Live Before We Die The Addams Family Theme Title: Ain't Misbehavin' - vocal selections Author: Henderson, Luther Publisher: Hal Leonard Publishing Corporation Description: Vocal selections from the musical. Contains: Ain't Misbehavin (What Did I Do to Be So) Black and Blue (Get Some) Cash For Your Trash Handful of Keys Honeysuckle Rose How Ya Baby I Can't Give You Anything But Love It's a Sin To Tell A Lie I've Got A Felling I'm Falling The Jitterbug Waltz The Joint is Jumping Keepin' Out of Mischief Now The Ladies Who Sing With the Band Looking' Good But Feelin' Bad Lounging at the Waldorf Mean to Me Off-Time Squeeze Me 'Tain't Nobody's Biz-ness If I Do Title: Aladdin and Out - opera A comic opera in three acts Author: Edmonds, Fred Hewitt, Thomas J. -

Three Generations of Southern Food and Culture

Three Generations of Southern Food & Culture An Oral History of North Carolina By Margaux Novak November 2016 Margaux Novak 1 Cast of Mothers & Daughters: Spanning Three Generations Elizabeth Hill (Mother of Teresa): Born 1926. Youngest of eleven siblings across a twenty-year span. Food brought the family together then, and it’s how she taught her children to come together ever since. Teresa Hill Lee (Daughter of Elizabeth): Born 1946. Senior Mary-Kay Consultant. Opened a Southern Catering business through her Wilmington Women’s Group to raise money for charity. Robin Wenskus (Step-daughter of Elizabeth): Born 1950. Interior Designer. Grew up in a large Southern family in coastal North Carolina. -- Nan Smith (Mother of Noelle): Born 1948. Retired elementary school teacher. Renowned Southern cook and hospitality expert in her area. Noelle Smith Parker (Daughter of Nan): Millennial, born 1988. University professor in her late twenties. Part of a younger generation when it comes to southern heritage. Introduction: Southern culture and food, for many, is an intermixed and tightly connected concept. There are hundreds of years of history—economic, political, and social— wrapped up in what it means to be Southern. It is each layer of this history that forged Southern tradition, food, and culture. Of course, every part of the South claims its own idiosyncrasies, so I chose to focus on my home state of North Carolina. North Carolina is a unique place for many reasons: It is one of the only states to have mountains, piedmont, and a coastal region. Much of the Civil War was fought on North Carolinian soil, and so there are many historical and momentous events that took place there. -

What Took You So Long

What Took PATRICKRYDMAN You So Long STEREO FRCD054 SHE’S BACK AGAIN GINGERBREAD MAN THE BAD GUYS ALWAYS LOSE THE FEELING (THAT WE LABEL LOVE) Good morning, sir I met the Gingerbread Man Aren’t the stars about to fall I’ve been told the heart is just a muscle and it What seems to be the matter Last night in an abandoned street Can’t you feel the magic wonder of it all pumps your blood Ah yes, it’s her He was tall and tan Maybe fortune, maybe fame It keeps your body warm when it is getting cold She left last week and now it’s all a mess Telling truths while stomping his feet Everyone will know your name It’s simply a machine that doesn’t stop Only emptiness That’s the game Night and day, it keeps on beating patiently for Brown in a blue tie Still, one problem less Nothing ventured, baby – nothing gained zero pay Talking to the red sky You read the paper, nothing has happened And beaten up by pain and fear it will remain His words made me shiver So better start to strut your stuff It is all the same Your faithful servant, moving every drop As he kept rolling his eyes Once you get them hooked they cannot get enough People are stupid, yeah they’re quite deranged If anyone can it’s the Gingerbread Man Fool them once and fool them twice But here’s the deal – my heart has changed Seems they’ll never change Listen to some good advice: my mind You catch your breath and sigh The Gingerbread Man Feed them lies And now I feel instead of thinking all of the time Walked with me down the beat up lane ’Cause she’s back again Rig the tables and let’s roll -

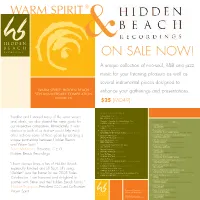

Hidden Beach CD

WARM SPIRIT&® ON SALE NOW! A unique collection of neo-soul, R&B and jazz music for your listening pleasure as well as several instrumental pieces designed to WARM SPIRIT HIDDEN BEACH enhance your gatherings and presentations. 5TH ANNIVERSARY COMPILATION DOUBLE CD $25 [MO49] WARM SPIRIT ||| CD 1 1. A Long Walk (4:41) “Nadine and I shared many of the same values JILL SCOTT Who Is Jill Scott? 2. Gangster's Paradise Feat. Karen Briggs (5:48) W WARM SPIRIT ||| CD 2 W and ideals, we also shared the same goals for VARIOUS ARTISTS Unwrapped Vol. 2 A 1. Golden (3:51) A R 3. Leaving You (4:58) JILL SCOTT Beautifully Human R M our respective companies. Immediately, it was LINA The Inner Beauty Movement M 2. Far Away (4:18) S 4. Weather The Storm (4:51) S P obvious to both of us that we could help each Surrender To Love KINDRED THE FAMILY SOUL Surrender To Love P I KINDRED THE FAMILY SOUL I R 3. P.I.M.P. feat. Jeff Lorber & Dennis Nelson (4:52) R I 5. Expect A Miracle (5:13) I T other achieve some of these goals by creating a VARIOUS ARTISTS Unwrapped Vol. 3 T BRENDA RUSSELL Paris Rain H 6. Love Me Anyway (5:06) 4. We Are One (6:54) H I unique partnership between Hidden Beach I D BEBE WINANS Dream MIKE PHILLIPS Uncommon Denominator D D 7. He Loves Me (Lyzel In E Flat) (4:45) 5. Hot In Herre (5:42) D E and Warm Spirit.” E N JILL SCOTT Who Is Jill Scott? VARIOUS ARTISTS Unwrapped Vol. -

CONTEMPORARY STAGING OP IRWIN Shawf 3 BURY the DEAD

AN ANALYSIS AND PRODUCTION BOOK FOR A CONTEMPORARY STAGING OP IRWIN SHAWf 3 BURY THE DEAD APPROVED: Ka.1 or Professor Inor Professor Chairman, jjeparfcinent ofNSpeech and Drama Dean of the Graduate School Holland, Charles A. , An Analysis and Production Book For A Contemporary Staging of Irwin Shaw' s Bury the Dead. Master of Arts (Speech and Drama), August, 1973, 176 pp.i bibliography, 32 titles. The problem of this thesis is concerned with the directing and producing of a 1936 peace play, Bury the Dead, by Irwin Shaw. The production attempts to heighten the relevancy of the play to modern audiences. The project experiments with applying contemporary machines and tech- niques to a dated script containing realistic dialogue, a dualistic point of view, and a surrealistic idea of dead soldiers rising from their graves. The task generates a particular responsibility and challenge in that the use of contemporary machinery must be carefully chosen in such a way that it does not interfere with the message of the play. The thesis is organized into five chapters. The first chapter is introductory in nature: it reports selected critical commentary on Shaw's play and its original production, the choice of the play., a statement of the problem, and the importance of the play. The second chapter contains an analysis of the play. It presents an analysis in relation to the experimental aspects of the production. It further discusses the director's adaptation in relation to Shaw's purpose and original intent, Prom this analysis a general concept of production in reference to the style of presentation is established, The third chapter includes a detailed inves- tigation of the production problems, including changes made to the original script, the stage setting, casting, rehearsal, publicity, contemporary machinery, lighting and sound. -

[Note: the Songs Appearing in Brackets Were Played on the Radio at This Point in the Interview.]

[Note: the songs appearing in brackets were played on the radio at this point in the interview.] (TV=Tommy Vance / RW=Roger Waters) TV: Where did the idea come from? RW: Well, the idea for 'The Wall' came from ten years of touring, rock shows, I think, particularly the last few years in '75 and in '77 we were playing to very large audiences, some of whom were our old audience who'd come to see us play, but most of whom were only there for the beer, in big stadiums, and, er, consequently it became rather an alienating experience doing the shows. I became very conscious of a wall between us and our audience and so this record started out as being an expression of those feelings. TV: But it goes I think a little deeper than that, because the record actually seems to start at the beginning of the character's life. RW: The story has been developed considerably since then, this was two years ago [1977], I started to write it, and now it's partly about a live show situation--in fact the album starts off in a live show, and then it flashes back and traces a story of a character, if you like, of Pink himself, whoever he may be. But initially it just stemmed from shows being horrible. TV: When you say "horrible" do you mean that really you didn't want to be there? RW: Yeah, it's all, er, particularly because the people who you're most aware of at a rock show on stage are the front 20 or 30 rows of bodies.