Oral History Interview with William T. Wiley, 1997 October 8-November 20

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Download Press Release [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4930/download-press-release-pdf-4930.webp)

Download Press Release [PDF]

NICELLE BEAUCHENE GALLERY Maija Peeples-Bright SEALabrate with Maija! May 31-June 30, 2019 Opening Reception: Friday, May 31, 6-8 pm Nicelle Beauchene is pleased to present a solo exhibition of paintings by Maija Peeples-Bright, spanning three decades of her career from 1971-1996. Titled SEALabrate with Maija!, this exhibition is the artist’s first in New York. For nearly thirty years, Peeples-Bright exhibited at Adeliza McHugh’s Candy Store Gallery in Folsom, California. McHugh was in her fifties and had no formal experience in the art world when she decided to open an art gallery after the local health department shut down her almond nougat business. The Candy Store Gallery became synonymous with the Funk Art movement and Peeples-Bright showed there along side Robert Arneson, Clayton Bailey, Roy De Forest, David Gilhooly, Irv Marcus, and William T. Wiley. Peeples-Bright was introduced to McHugh through her teacher at UC Davis Robert Arneson and had her first exhibition there in 1965. In the late 1960’s, frustrated with the limitations of Funk, Peeples-Bright was a founding member of the Northern Californian movement dubbed Nut Art. Along with Clayton Bailey, Roy De Forest, David Gilhooly, and David Zack, Nut artists sought to create fantasy worlds that were reflective of each artist’s idiosyncrasies and self-created mythologies. Peeples-Bright and others adopted alter egos for this purpose, she was known as “Maija Woof.” In 1972 at California State University Hayward, Clayton Bailey organized the first Nut Art exhibition. A manifesto written for the occasion by Roy De Forest declared: “THE WORK OF A PECULIAR AND ECCENTRIC NUT CAN TRULY BE CALLED ‘NUT ART’… THE NUT ARTIFICER TRAVELS IN A PHANTASMAGORIC MICRO-WORLD, SMALL AND EXTREMELY COMPACT, AS IS THE LIGHT OF A DWARF STAR IMPLODING INWARD.” SEALabrate with Maija! is a glimpse into the colorful world of the artist’s creation. -

Oral History Interview with Robert David Brady

Oral history interview with Robert David Brady Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 General............................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Oral history interview with Robert David Brady -

Christine Giles Bill Bob and Bill.Pdf

William Allan, Robert Hudson and William T. Wiley A Window on History, by George. 1993 pastel, Conte crayon, charcoal, graphite and acrylic on canvas 1 61 /2 x 87 '12 inches Courtesy of John Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco, California Photograph by Cesar Rubio / r.- .. 12 -.'. Christine Giles and Hatherine Plake Hough ccentricity, individualism and nonconformity have been central to San Fran cisco Bay Area and Northern California's spirit since the Gold Rush era. Town Enames like Rough and Ready, Whiskey Flats and "Pair of Dice" (later changed to Paradise) testify to the raw humor and outsider self-image rooted in Northern California culture. This exhibition focuses on three artists' exploration of a different western frontier-that of individual creativity and collaboration. It brings together paintings, sculptures, assemblages and works on paper created individually and collabora tively by three close friends: William Allan, Robert Hudson and William T. Wiley. ·n, Bob and Bill William Allan, the eldest, was born in Everett, Washington, in 1936, followed by Wiley, born in Bedford, Indiana, in 1937 and Hudson, born in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1938. Their families eventually settled in Richland, in southeast Washington, where the three met and began a life-long social and professional relationship. Richland was the site of one of the nation's first plutonium production plants-Hanford Atomic Works. 1 Hudson remembers Richland as a plutonium boom town: the city's population seemed to swell overnight from a few thousand to over 30,000. Most of the transient population lived in fourteen square blocks filled with trailer courts. -

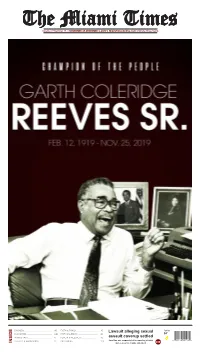

INSIDE and Coerced to Change Statement 10D Editorials Cartoons Opinions Letters

Volume 97 Number 15 | NOVEMBER 27-DECEMBER 3, 2019 | MiamiTimesOnline.com | Ninety-Three Cents BUSINESS ................................................. 8B FAITH & FAMILY ...................................... 7D Lawsuit alleging sexual Today CLASSIFIED ............................................. 11B FAITH CALENDAR ................................... 8D 84° IN GOOD TASTE ......................................... 1C HEALTH & WELLNESS ............................. 9D assault coverup settled LIFESTYLE HAPPENINGS ....................... 5C OBITUARIES ............................................. 12D Jane Doe was suspended after reporting attacks 8 90158 00100 0 INSIDE and coerced to change statement 10D Editorials Cartoons Opinions Letters VIEWPOINT BLACKS MUST CONTROL THEIR OWN DESTINY | NOVEMBER 27-DECEMBER 3, 2019 | MiamiTimesOnline.com MEMBER: National Newspaper Periodicals Postage Credo Of The Black Press Publisher Association paid at Miami, Florida Four Florida outrages: (ISSN 0739-0319) The Black Press believes that America MEMBER: The Newspaper POSTMASTER: Published Weekly at 900 NW 54th Street, can best lead the world from racial and Association of America Send address changes to Miami, Florida 33127-1818 national antagonism when it accords Subscription Rates: One Year THE MIAMI TIMES, The wealthy flourish, Post Office Box 270200 to every person, regardless of race, $65.00 – Two Year $120.00 P.O. Box 270200 Buena Vista Station, Miami, Florida 33127 creed or color, his or her human and Foreign $75.00 Buena Vista Station, Miami, FL Phone 305-694-6210 legal rights. Hating no person, fearing 7 percent sales tax for Florida residents 33127-0200 • 305-694-6210 the poor die H.E. SIGISMUND REEVES Founder, 1923-1968 no person, the Black Press strives to GARTH C. REEVES JR. Editor, 1972-1982 help every person in the firm belief that ith President Trump’s impeachment hearing domi- GARTH C. REEVES SR. -

DILEXI GALLERY Multi-Venue Retrospective

DILEXI GALLERY Multi-Venue Retrospective Taking place at: Brian Gross Fine Art / San Francisco Crown Point Press / San Francisco Parker Gallery / Los Angeles Parrasch Heijnen Gallery / Los Angeles The Landing / Los Angeles with a related exhibition at: Marc Selwyn Fine Art / Los Angeles The Dilexi Multi-Venue Retrospective The Dilexi Gallery in San Francisco operated in the years and Southern Californian artists that had begun with his 1958-1969 and played a key role in the cultivation and friendship and tight relationship with well-known curator development of contemporary art in the Bay Area and Walter Hopps and the Ferus Gallery. beyond. The Dilexi’s young director Jim Newman had an implicit understanding of works that engaged paradigmatic Following the closure of its San Francisco venue, the Dilexi shifts, embraced new philosophical constructs, and served went on to become the Dilexi Foundation commissioning as vessels of sacred reverie for a new era. artist films, happenings, publications, and performances which sought to continue its objectives within a broader Dilexi presented artists who not only became some of the cultural sphere. most well-known in California and American art, but also notably distinguished itself by showcasing disparate artists This multi-venue exhibition, taking place in the summer of as a cohesive like-minded whole. It functioned much like 2019 at five galleries in both San Francisco and Los Angeles, a laboratory with variant chemical compounds that when rekindles the Dilexi’s original spirit of alliance. This staging combined offered a powerful philosophical formula that of multiple museum quality shows allows an exploration of actively transmuted the cultural landscape, allowing its the deeper philosophic underpinnings of the gallery’s role artists to find passage through the confining culture of the as a key vehicle in showcasing the breadth of ideas taking status quo toward a total liberation and mystical revolution. -

Wonderful! 143: Rare, Exclusive Gak Published July 29Th, 2020 Listen on Themcelroy.Family

Wonderful! 143: Rare, Exclusive Gak Published July 29th, 2020 Listen on TheMcElroy.family [theme music plays] Rachel: I'm gonna get so sweaty in here. Griffin: Are you? Rachel: It is… hotototot. Griffin: Okay. Is this the show? Are we in it? Rachel: Hi, this is Rachel McElroy! Griffin: Hi, this is Griffin McElroy. Rachel: And this is Wonderful! Griffin: It‘s gettin‘ sweaaatyyy! Rachel: [laughs] Griffin: It‘s not—it doesn‘t feel that bad to me. Rachel: See, you're used to it. Griffin: Y'know what it was? Mm, I had my big fat gaming rig pumping out pixels and frames. Comin‘ at me hot and heavy. Master Chief was there. Just so fuckin‘—just poundin‘ out the bad guys, and it was getting hot and sweaty in here. So I apologize. Rachel: Griffin has a very sparse office that has 700 pieces of electronic equipment in it. Griffin: True. So then, one might actually argue it‘s not sparse at all. In fact, it is filled with electronic equipment. Yeah, that‘s true. I imagine if I get the PC running, I imagine if I get the 3D printer running, all at the same time, it‘s just gonna—it could be a sweat lodge. I could go on a real journey in here. But I don‘t think it‘s that bad, and we‘re only in here for a little bit, so let‘s… Rachel: And I will also say that a lot of these electronics help you make a better podcast, which… is a timely thing. -

Manuel Neri LIMITED EDITION BOOKS

BIBLIOGRAPHY - Manuel Neri LIMITED EDITION BOOKS: Klimenko, Mary Julia. She Said: I Tell You It Doesn't Hurt Me. San Diego, CA: Brighton Press, 1991. Handpainted etchings by Manuel Neri. Limited edition of 33. _____. Territory. San Diego, CA: Brighton Press, 1993. Photolithograph illustrations by Manuel Neri with one original drawing. Limited edition of 55. _____. Crossings/Chassé-croisé. Berkeley, CA: Editions Koch, 2003. Photographs by M. Lee Fatherree; original artwork by Manuel Neri. Limited edition of 45 plus 10 deluxe editions. BOOKS: Albright, Thomas. Art in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1945–1980. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985. Andersen, Wayne. American Sculpture in Process: 1930–1970. Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1975. Illus.: Figure, 1963. Anderson, Mark; Bruce, Chris; Wells, Keith; with essay by Jim Dine. Extending the Artist's Hand: Contemporary Sculpture from Walla Walla Foundry. Pullman, WA: Museum of Art, Washington State University, 2004. Illus.: Posturing Series No. 3, 1980; Untitled Standing Figure No. 5, 1980; Virgin Mary, 2003. Barron, Stephanie; Bernstein, Sherri; Fort, Ilene Susan. Made in California: Art, Image, and Identity, 1900–2000. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; University of California Press, 2000. Cancel, Luis R., et al. The Latin American Spirit: Art and Artists in the United States, 1920–1970. Bronx: Bronx Museum of the Arts and Harry N. Abrams, 1988. Illus.: Untitled Standing Figure, 1957. Cándida Smith, Richard. Utopia and Dissent: Art, Poetry, and Politics in California. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1995. Clark, Garth, and Hughto, Margie. A Century of Ceramics in the United States, 1878–1978. -

Visions of the Davis Art Center

Lost and Found: Visions of the Davis Art Center Permanent Collection 1967-1992 October 8 – November 19, 2010 This page is intentionally blank 2 Lost and Found: Visions of the Davis Art Center In the fall of 2008, as the Davis Art Center began preparing for its 50th anniversary, a few curious board members began to research the history of a permanent collection dating back to the founding of the Davis Art Center in the 1960s. They quickly recognized that this collection, which had been hidden away for decades, was a veritable treasure trove of late 20th century Northern California art. It’s been 27 years since the permanent collection was last exhibited to the public. Lost and Found: Visions of the Davis Art Center brings these treasures to light. Between 1967 and 1992 the Davis Art Center assembled a collection of 148 artworks by 92 artists. Included in the collection are ceramics, paintings, drawings, lithographs, photographs, mixed media, woodblocks, and textiles. Many of the artists represented in the collection were on the cutting edge of their time and several have become legends of the art world. Lost and Found: Visions of the Davis Art Center consists of 54 works by 34 artists ranging from the funky and figurative to the quiet and conceptual. This exhibit showcases the artistic legacy of Northern California and the prescient vision of the Davis Art Center’s original permanent collection committee, a group of volunteers who shared a passion for art and a sharp eye for artistic talent. Through their tireless efforts acquiring works by artists who were relatively unknown at the time, the committee created what would become an impressive collection that reveals Davis’ role as a major player in a significant art historical period. -

Life Writing Prize 2021

Life Writing Prize 2021 Longlist Anthology Life Writing Prize 2021 Longlist Anthology The Life Writing Prize has been made possible thanks to a generous donation by Joanna Munro. We’d also like to thank the Goldsmiths Writers’ Centre for their partnership on the Prize. First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Spread the Word. Copyright © remains with the authors. All rights reserved. CONTENTS Foreword 5 Santanu Bhattacharya The Nicer One* 8 Carla Jenkins Carving 21 Matt Taylor Tromode House 36 Sara Doctors Grief Bacon 46 SJ Lyon People That Might Be Us 61 Lois Warner White Lines* 68 Nic Wilson By The Wayside 81 Laura McDonagh Commonplace 94 Penny Kiley How To Watch Your Mother Die 108 Imogen Phillips Taken and Left* 119 Susan Daniels The Secret* 136 Pete Williams The Strawbs 143 Acknowledgements 158 About Spread the Word 159 *Trigger warning: these stories include references to sexual assault, violence, rape and child sex abuse. FOREWORD The Spread the Word Life Writing Prize, in association with Goldsmiths Writers’ Centre, is now in its fifth year. The twelve pieces featured in this anthology form the longlist selected from over 900 entries sent in from across the UK. In a challenging year they are proof that life writing is thriving. As with last year, the judging took place virtually with Catherine Cho, Damian Barr and Frances Wilson deliberating to pick a shortlist of six, followed by two highly commended entries and one winner. The winner of the Life Writing Prize 2021 is The Nicer One by Santanu Bhattacharya, a piece that mixes the familiar experience of bumping into a childhood classmate at a party with a harrowing retelling of schoolboy abuse. -

Publication Management, Content Strategy & Execution Specialty Writing Production & Consulting

Content Strategy & Execution Content Strategy 843.513.7535 ~ [email protected] riverbendcustomcontent.com Professional Profile Respected leader of creative teams with proven ability to conceptualize and orchestrate communications campaigns that effectively build and reinforce brand. Collaborative team player adept at transforming complex ideas and subject matter into digestible information that connects, enlightens and engages target markets and segments. Select Professional Achievements Established and executed a content/thought leadership communications program to enhance the Elliott Davis brand and strengthen the firm’s position as a diversified business solutions provider offering a full spectrum of professional financial services and consulting. Content Strategy Created and directed the National Golf Course Owners Association’s first Comprehensive In conjunction with CMO and Content Strategy, a three-phase, multi-year plan that established the four pillars under marketing director, developed a which all NGCOA educational content was categorized and developed. comprehensive plan and editorial calendar to create, schedule and Spearheaded two complete repositionings of Golf Business magazine, re-establishing the deliver content and collateral for title as the golf industry’s preeminent business publication. all Elliott Davis business units. Garnered multiple awards for writing and publication excellence from the Society of National Association Publications, Turf & Ornamental Communications Association, International Network of Golf and Carolinas Golf Reporters Association. Areas of Specialty & Expertise Editorial, Creative & Publication Management, Content Strategy & Execution Specialty Writing Production & Consulting Experienced professional Award-winning writer whose Veteran, award-winning skilled in the development articles and columns have magazine editor with more and creation of content, appeared in numerous national, than two decades of experience educational curricula and regional and local publications. -

As I Am Painting the Figure in Post-War San Francisco Curated by Francis Mill and Michael Hackett

As I Am Painting the Figure in Post-War San Francisco Curated by Francis Mill and Michael Hackett David Park, Figure with Fence, 1953, oil on canvas, 35 x 49 inches O P E N I N G R E C E P T I O N April 7, 2016, 5-7pm E X H I B I T I O N D A T E S April 7 - May 27, 2016 Hackett | Mill presents As I Am: Painting the Figure in Post-War San Francisco as it travels to our gallery from the New York Studio School. This special exhibition is a major survey of artwork by the founding members of the Bay Area Figurative Movement. Artists included are David Park, Elmer Bischoff and Richard Diebenkorn, as well as Joan Brown, William Theophilus Brown, Frank Lobdell, Manuel Neri, Nathan Oliveira, James Weeks and Paul Wonner. This exhibition examines the time period of 1950-1965, when a group of artists in the San Francisco Bay Area decided to pursue figurative painting during the height of Abstract Expressionism. San Francisco was the regional center for a group of artists who were working in a style sufficiently independent from the New York School, and can be credited with having forged a distinct variant on what was the first American style to have international importance. The Bay Area Figurative movement, which grew out of and was in reaction to both West Coast and East Coast varieties of Abstract Expressionism, was a local phenomenon and yet was responsive to the most topical national tendencies. -

Inside and Around the 6 Gallery with Co-Founder Deborah Remington

Inside and Around the 6 Gallery with Co-Founder Deborah Remington Nancy M. Grace The College of Wooster As the site where Allen Ginsberg introduced “Howl” to the world on what the record most reliably says is Oct. 7, 1955, the 6 Gallery resonates for many as sacred ground, something akin to Henry David Thoreau’s gravesite in Concord, Massachusetts, or Edgar Allen Poe’s dorm room at the University of Virginia, or Willa Cather’s clapboard home in Red Cloud, Nebraska. Those who travel today to the site at 3119 Filmore in San Francisco find an upscale furniture boutique called Liv Furniture (Photos below courtesy of Tony Trigilio). Nonetheless, we imagine the 6 as it might have been, a vision derived primarily through our reading of The Dharma Bums by Jack Kerouac and “Poetry at The 6” by Michael McClure. Continuing the recovery work related to women associated with the Beat Generation that I began about ten years ago with Ronna Johnson of Tufts University, I’ve long 1 wanted to seek out a perspective on the 6 Gallery that has been not been integrated into our history of the institution: That of Deborah Remington, a co-founder – and the only woman co-founder—of the gallery. Her name appears in a cursory manner in descriptions of the 6, but little else to give her substance and significance. As sometimes happens, the path I took to find Remington was not conventional. In fact, she figuratively fell into my lap. Allison Schmidt, a professor of education at The College of Wooster where I teach, happens to be her cousin, something I didn’t know until Schmidt contacted me about two years ago and told me that Remington might be interested in talking with me as part of a family oral history project.