Moser on William Wiley.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with William T. Wiley, 1997 October 8-November 20

Oral history interview with William T. Wiley, 1997 October 8-November 20 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview PAUL KARLSTROM: Smithsonian Institution, an interview with William T. Wiley, at his studio in Woodacre, California, north of San Francisco. The date is October 8, 1997. This is the first session in what I hope will be a somewhat extensive series. The interviewer for the archives is Paul Karlstrom. Okay, here we go, Bill. I've been looking forward to this interview for quite a long time, ever since we met back in, it was the mid-seventies, as a matter of fact. At that time, in fact, I visited right here in this studio. We talked about your papers and talked about sometime doing an interview, but for one reason or another, it didn't happen. Well, the advantage to that, as I mentioned earlier, is that a lot has transpired since then, which means we have a lot more to talk about. Anyway, we can't go backwards, and here we are. I wanted to start out by setting the stage for this interview. As I mentioned, Archive's [of American Art] interviews are comprehensive and tend to move along sort of biographical, chronological structure, at least it gives something to follow through. But what I would like to do first of all, just very briefly, is kind of set the stage, and by way of an observation that I would like to make, which is also, I think, a compliment. -

Oral History Interview with Robert David Brady

Oral history interview with Robert David Brady Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 General............................................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Oral history interview with Robert David Brady -

Christine Giles Bill Bob and Bill.Pdf

William Allan, Robert Hudson and William T. Wiley A Window on History, by George. 1993 pastel, Conte crayon, charcoal, graphite and acrylic on canvas 1 61 /2 x 87 '12 inches Courtesy of John Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco, California Photograph by Cesar Rubio / r.- .. 12 -.'. Christine Giles and Hatherine Plake Hough ccentricity, individualism and nonconformity have been central to San Fran cisco Bay Area and Northern California's spirit since the Gold Rush era. Town Enames like Rough and Ready, Whiskey Flats and "Pair of Dice" (later changed to Paradise) testify to the raw humor and outsider self-image rooted in Northern California culture. This exhibition focuses on three artists' exploration of a different western frontier-that of individual creativity and collaboration. It brings together paintings, sculptures, assemblages and works on paper created individually and collabora tively by three close friends: William Allan, Robert Hudson and William T. Wiley. ·n, Bob and Bill William Allan, the eldest, was born in Everett, Washington, in 1936, followed by Wiley, born in Bedford, Indiana, in 1937 and Hudson, born in Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1938. Their families eventually settled in Richland, in southeast Washington, where the three met and began a life-long social and professional relationship. Richland was the site of one of the nation's first plutonium production plants-Hanford Atomic Works. 1 Hudson remembers Richland as a plutonium boom town: the city's population seemed to swell overnight from a few thousand to over 30,000. Most of the transient population lived in fourteen square blocks filled with trailer courts. -

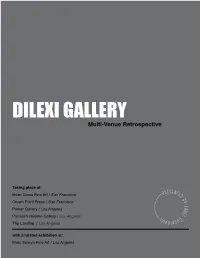

DILEXI GALLERY Multi-Venue Retrospective

DILEXI GALLERY Multi-Venue Retrospective Taking place at: Brian Gross Fine Art / San Francisco Crown Point Press / San Francisco Parker Gallery / Los Angeles Parrasch Heijnen Gallery / Los Angeles The Landing / Los Angeles with a related exhibition at: Marc Selwyn Fine Art / Los Angeles The Dilexi Multi-Venue Retrospective The Dilexi Gallery in San Francisco operated in the years and Southern Californian artists that had begun with his 1958-1969 and played a key role in the cultivation and friendship and tight relationship with well-known curator development of contemporary art in the Bay Area and Walter Hopps and the Ferus Gallery. beyond. The Dilexi’s young director Jim Newman had an implicit understanding of works that engaged paradigmatic Following the closure of its San Francisco venue, the Dilexi shifts, embraced new philosophical constructs, and served went on to become the Dilexi Foundation commissioning as vessels of sacred reverie for a new era. artist films, happenings, publications, and performances which sought to continue its objectives within a broader Dilexi presented artists who not only became some of the cultural sphere. most well-known in California and American art, but also notably distinguished itself by showcasing disparate artists This multi-venue exhibition, taking place in the summer of as a cohesive like-minded whole. It functioned much like 2019 at five galleries in both San Francisco and Los Angeles, a laboratory with variant chemical compounds that when rekindles the Dilexi’s original spirit of alliance. This staging combined offered a powerful philosophical formula that of multiple museum quality shows allows an exploration of actively transmuted the cultural landscape, allowing its the deeper philosophic underpinnings of the gallery’s role artists to find passage through the confining culture of the as a key vehicle in showcasing the breadth of ideas taking status quo toward a total liberation and mystical revolution. -

Manuel Neri LIMITED EDITION BOOKS

BIBLIOGRAPHY - Manuel Neri LIMITED EDITION BOOKS: Klimenko, Mary Julia. She Said: I Tell You It Doesn't Hurt Me. San Diego, CA: Brighton Press, 1991. Handpainted etchings by Manuel Neri. Limited edition of 33. _____. Territory. San Diego, CA: Brighton Press, 1993. Photolithograph illustrations by Manuel Neri with one original drawing. Limited edition of 55. _____. Crossings/Chassé-croisé. Berkeley, CA: Editions Koch, 2003. Photographs by M. Lee Fatherree; original artwork by Manuel Neri. Limited edition of 45 plus 10 deluxe editions. BOOKS: Albright, Thomas. Art in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1945–1980. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985. Andersen, Wayne. American Sculpture in Process: 1930–1970. Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1975. Illus.: Figure, 1963. Anderson, Mark; Bruce, Chris; Wells, Keith; with essay by Jim Dine. Extending the Artist's Hand: Contemporary Sculpture from Walla Walla Foundry. Pullman, WA: Museum of Art, Washington State University, 2004. Illus.: Posturing Series No. 3, 1980; Untitled Standing Figure No. 5, 1980; Virgin Mary, 2003. Barron, Stephanie; Bernstein, Sherri; Fort, Ilene Susan. Made in California: Art, Image, and Identity, 1900–2000. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art; University of California Press, 2000. Cancel, Luis R., et al. The Latin American Spirit: Art and Artists in the United States, 1920–1970. Bronx: Bronx Museum of the Arts and Harry N. Abrams, 1988. Illus.: Untitled Standing Figure, 1957. Cándida Smith, Richard. Utopia and Dissent: Art, Poetry, and Politics in California. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1995. Clark, Garth, and Hughto, Margie. A Century of Ceramics in the United States, 1878–1978. -

Visions of the Davis Art Center

Lost and Found: Visions of the Davis Art Center Permanent Collection 1967-1992 October 8 – November 19, 2010 This page is intentionally blank 2 Lost and Found: Visions of the Davis Art Center In the fall of 2008, as the Davis Art Center began preparing for its 50th anniversary, a few curious board members began to research the history of a permanent collection dating back to the founding of the Davis Art Center in the 1960s. They quickly recognized that this collection, which had been hidden away for decades, was a veritable treasure trove of late 20th century Northern California art. It’s been 27 years since the permanent collection was last exhibited to the public. Lost and Found: Visions of the Davis Art Center brings these treasures to light. Between 1967 and 1992 the Davis Art Center assembled a collection of 148 artworks by 92 artists. Included in the collection are ceramics, paintings, drawings, lithographs, photographs, mixed media, woodblocks, and textiles. Many of the artists represented in the collection were on the cutting edge of their time and several have become legends of the art world. Lost and Found: Visions of the Davis Art Center consists of 54 works by 34 artists ranging from the funky and figurative to the quiet and conceptual. This exhibit showcases the artistic legacy of Northern California and the prescient vision of the Davis Art Center’s original permanent collection committee, a group of volunteers who shared a passion for art and a sharp eye for artistic talent. Through their tireless efforts acquiring works by artists who were relatively unknown at the time, the committee created what would become an impressive collection that reveals Davis’ role as a major player in a significant art historical period. -

As I Am Painting the Figure in Post-War San Francisco Curated by Francis Mill and Michael Hackett

As I Am Painting the Figure in Post-War San Francisco Curated by Francis Mill and Michael Hackett David Park, Figure with Fence, 1953, oil on canvas, 35 x 49 inches O P E N I N G R E C E P T I O N April 7, 2016, 5-7pm E X H I B I T I O N D A T E S April 7 - May 27, 2016 Hackett | Mill presents As I Am: Painting the Figure in Post-War San Francisco as it travels to our gallery from the New York Studio School. This special exhibition is a major survey of artwork by the founding members of the Bay Area Figurative Movement. Artists included are David Park, Elmer Bischoff and Richard Diebenkorn, as well as Joan Brown, William Theophilus Brown, Frank Lobdell, Manuel Neri, Nathan Oliveira, James Weeks and Paul Wonner. This exhibition examines the time period of 1950-1965, when a group of artists in the San Francisco Bay Area decided to pursue figurative painting during the height of Abstract Expressionism. San Francisco was the regional center for a group of artists who were working in a style sufficiently independent from the New York School, and can be credited with having forged a distinct variant on what was the first American style to have international importance. The Bay Area Figurative movement, which grew out of and was in reaction to both West Coast and East Coast varieties of Abstract Expressionism, was a local phenomenon and yet was responsive to the most topical national tendencies. -

Inside and Around the 6 Gallery with Co-Founder Deborah Remington

Inside and Around the 6 Gallery with Co-Founder Deborah Remington Nancy M. Grace The College of Wooster As the site where Allen Ginsberg introduced “Howl” to the world on what the record most reliably says is Oct. 7, 1955, the 6 Gallery resonates for many as sacred ground, something akin to Henry David Thoreau’s gravesite in Concord, Massachusetts, or Edgar Allen Poe’s dorm room at the University of Virginia, or Willa Cather’s clapboard home in Red Cloud, Nebraska. Those who travel today to the site at 3119 Filmore in San Francisco find an upscale furniture boutique called Liv Furniture (Photos below courtesy of Tony Trigilio). Nonetheless, we imagine the 6 as it might have been, a vision derived primarily through our reading of The Dharma Bums by Jack Kerouac and “Poetry at The 6” by Michael McClure. Continuing the recovery work related to women associated with the Beat Generation that I began about ten years ago with Ronna Johnson of Tufts University, I’ve long 1 wanted to seek out a perspective on the 6 Gallery that has been not been integrated into our history of the institution: That of Deborah Remington, a co-founder – and the only woman co-founder—of the gallery. Her name appears in a cursory manner in descriptions of the 6, but little else to give her substance and significance. As sometimes happens, the path I took to find Remington was not conventional. In fact, she figuratively fell into my lap. Allison Schmidt, a professor of education at The College of Wooster where I teach, happens to be her cousin, something I didn’t know until Schmidt contacted me about two years ago and told me that Remington might be interested in talking with me as part of a family oral history project. -

Manuel Neri CV

MANUEL NERI BORN: 1930, Sanger, CA EDUCATION: 1949-50 San Francisco City College, San Francisco, CA 1951-52 University of California, Berkeley 1951-56 California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland 1956-58 California School of Fine Arts, San Francisco TEACHING: 1959-65 California School of Fine Arts, San Francisco, CA 1963-64 University of California, Berkeley, CA 1965-90 University of California, Davis, CA GRANTS AND AWARDS: 1953 Oakland Art Museum, First Award in Sculpture 1957 Oakland Art Museum, Purchase Award in Painting 1959 Nealie Sullivan Award, California School of Fine Arts, San Francisco 1963 San Francisco Art Institute, 82nd Annual Sculpture Award 1965 National Art Foundation Award 1970-75 University of California at Davis, Sculpture Grant 1979 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship 1980 National Endowment for the Arts, Individual Artist Grant 1982 American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, Academy-Institute Award in Art 1985 San Francisco Arts Commission, Award of Honor for Outstanding Achievement in Sculpture 1990 San Francisco Art Institute, Honorary Doctorate for Outstanding Achievement in Sculpture 1992 California College of Arts and Crafts, Honorary Doctorate 1995 Corcoran School of Art, Washington, DC, Honorary Doctorate 2004 International Sculpture Center, Lifetime Achievement Award in Contemporary Sculpture COMMISSIONS: 1980-82 Office of the State Architect, State of California, Commission for marble sculpture "Tres Marias" for The Bateson Building, Sacramento, CA 1987 North Carolina National Bank, Commission for marble sculpture "Española" for NCNB Tower, Tampa, FL The Linpro Company, Commission for marble sculpture "Passage" for the Christina Gateway Project, Wilmington, DE U.S. General Services Administration, Commission for marble sculpture "Ventana al Pacifico" for U.S. -

The San Francisco Bay Area 1945 – 1965

Subversive Art as Place, Identity and Bohemia: The San Francisco Bay Area 1945 – 1965 George Herms The Librarian, 1960. A text submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of The Glasgow School of Art For the degree of Master of Philosophy May 2015 © David Gracie 2015 i Abstract This thesis seeks evidence of time, place, and identity, as individualized artistic perspective impacting artists representing groups marginalized within dominant Western, specifically American culture, who lived in the San Francisco Bay Area between 1945–1965. Artists mirror the culture of the time in which they work. To examine this, I employ anthropological, sociological, ethnographic, and art historical pathways in my approach. Ethnic, racial, gender, class, sexual-orientation distinctions and inequities are examined via queer, and Marxist theory considerations, as well as a subjective/objective analysis of documented or existing artworks, philosophical, religious, and cultural theoretical concerns. I examine practice outputs by ethnic/immigrant, homosexual, and bohemian-positioned artists, exploring Saussurean interpretation of language or communicative roles in artwork and iconographic formation. I argue that varied and multiple Californian identities, as well as uniquely San Franciscan concerns, disseminated opposition to dominant United States cultural valuing and that these groups are often dismissed when produced by groups invisible within a dominant culture. I also argue that World War Two cultural upheaval induced Western societal reorganization enabling increased postmodern cultural inclusivity. Dominant societal repression resulted in ethnographic information being heavily coded by Bay Area artists when considering audiences. I examine alternative cultural support systems, art market accessibility, and attempt to decode product messages which reify enforced societal positioning. -

WINTER Exhibitions and Programs January 26–June 3, 2020

WINTER Exhibitions and Programs January 26–June 3, 2020 The Museum is free for all UC Davis | manettishrem.org | 530-752-8500 Calendar at a Glance January March April Continued 28 Creative Writing 26 Winter Season 4 Faculty Book Series: Reading Series: Celebration, Mark C. Jerng, Public Executions, 3–5 PM 4:30–6 PM 4:30–6 PM 11 The China Shop: 30 Visiting Artist Lecture: February Artists in Science Meg Shiffler, Labs, 4:30–6 PM 4:30–6 PM 5 Faculty Book Series: 12 Visiting Artist Lecture: Kriss Ravetto-Biagioli, 30 Artist Salon, Artist Francis Stark, 4:30–6 PM Tour 2.0 4:30–6 PM 7–8:30 PM 6 Thiebaud Endowed Photo: Meagan Lucy 26 Artist Salon, King Lecture: Leonardo Effect: Aerial Views, Drew, 4:30–6 PM Vantage Points and May 6 Artist Salon, Evolving Perspectives 6 The Scholar as Curator Decisions, Decisions: 7–8:30 PM Join us for a festive Series: Roger Sansi, Questions in the 4:30–6 PM Practice Winter Season Celebration 7–8:30 PM April 28 Graduate Exhibition Opening Celebration, 13 Davis Human Rights 2 Visiting Artist Lecture: 6–9 PM Lecture: Gilda Beatriz Cortez, Sunday, January 26, 3–5 PM Gonzales, 4:30–6 PM 30 Annual Art History 7–8:30 PM Graduate Colloquium, 18 Picnic Day, 1–4 PM First-generation UC Davis artists are featured in two compelling new exhibitions 23 Robert Arneson’s 11 AM–5 PM “Black Pictures”: opening at this event: Stephen Kaltenbach: The Beginning and The End and 26 Museum Talk, The Gwendolyn DuBois Gesture: The Human Figure After Abstraction | Selections from the Manetti Architecture of the June Shaw, 2:30 PM Shrem Museum. -

Monthly Muse – June 2021

View this email in your browser IMCA’s interim museum location has reopened! Please visit our newly refreshed website for information about the exhibition currently on view and everything else you need to know to plan an in-person visit. At this time advance booking is not required. In Remembrance: William T. Wiley William T. Wiley, a founder of the Bay Area Funk art movement, died on Sunday, April 25, 2021 at the age of 83. He was born in Bedford, IN and raised in Indiana, Texas, and Washington before moving to California to study at California School of Fine Arts (now San Francisco Art Institute), where he received his BFA in 1960 and MFA in 1962. Over the course of his career, Wiley pursued artistic expression in almost every conceivable medium—from painting, collage, found object construction, sculpture, and printmaking, to music, performance art, theater, and film. At the age of 23, Wiley presented his first solo exhibitions at the Staempfli Gallery (New York, NY) and the Hansen Fuller Gallery (San Francisco, CA). And a year after receiving his MFA, he joined the first-generation art faculty at UC Davis with fellow artists Robert Arneson, Roy DeForest, Manuel Neri, and Wayne Thiebaud. Some of his students included Deborah Butterfield, Stephen Laub, Bruce Nauman, and Richard Shaw, who subsequently became important and influential artists. “During the 60s, Wiley was grouped in with a loose movement largely centered around the Bay Area known as Funk art, which marked a turn away from the styles associated with Abstract Expressionism toward figurative modes that were cartoonish, surreal, and often crass.