Download Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral History Interview with William T. Wiley, 1997 October 8-November 20

Oral history interview with William T. Wiley, 1997 October 8-November 20 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview PAUL KARLSTROM: Smithsonian Institution, an interview with William T. Wiley, at his studio in Woodacre, California, north of San Francisco. The date is October 8, 1997. This is the first session in what I hope will be a somewhat extensive series. The interviewer for the archives is Paul Karlstrom. Okay, here we go, Bill. I've been looking forward to this interview for quite a long time, ever since we met back in, it was the mid-seventies, as a matter of fact. At that time, in fact, I visited right here in this studio. We talked about your papers and talked about sometime doing an interview, but for one reason or another, it didn't happen. Well, the advantage to that, as I mentioned earlier, is that a lot has transpired since then, which means we have a lot more to talk about. Anyway, we can't go backwards, and here we are. I wanted to start out by setting the stage for this interview. As I mentioned, Archive's [of American Art] interviews are comprehensive and tend to move along sort of biographical, chronological structure, at least it gives something to follow through. But what I would like to do first of all, just very briefly, is kind of set the stage, and by way of an observation that I would like to make, which is also, I think, a compliment. -

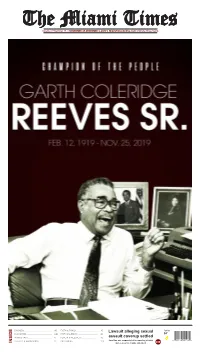

INSIDE and Coerced to Change Statement 10D Editorials Cartoons Opinions Letters

Volume 97 Number 15 | NOVEMBER 27-DECEMBER 3, 2019 | MiamiTimesOnline.com | Ninety-Three Cents BUSINESS ................................................. 8B FAITH & FAMILY ...................................... 7D Lawsuit alleging sexual Today CLASSIFIED ............................................. 11B FAITH CALENDAR ................................... 8D 84° IN GOOD TASTE ......................................... 1C HEALTH & WELLNESS ............................. 9D assault coverup settled LIFESTYLE HAPPENINGS ....................... 5C OBITUARIES ............................................. 12D Jane Doe was suspended after reporting attacks 8 90158 00100 0 INSIDE and coerced to change statement 10D Editorials Cartoons Opinions Letters VIEWPOINT BLACKS MUST CONTROL THEIR OWN DESTINY | NOVEMBER 27-DECEMBER 3, 2019 | MiamiTimesOnline.com MEMBER: National Newspaper Periodicals Postage Credo Of The Black Press Publisher Association paid at Miami, Florida Four Florida outrages: (ISSN 0739-0319) The Black Press believes that America MEMBER: The Newspaper POSTMASTER: Published Weekly at 900 NW 54th Street, can best lead the world from racial and Association of America Send address changes to Miami, Florida 33127-1818 national antagonism when it accords Subscription Rates: One Year THE MIAMI TIMES, The wealthy flourish, Post Office Box 270200 to every person, regardless of race, $65.00 – Two Year $120.00 P.O. Box 270200 Buena Vista Station, Miami, Florida 33127 creed or color, his or her human and Foreign $75.00 Buena Vista Station, Miami, FL Phone 305-694-6210 legal rights. Hating no person, fearing 7 percent sales tax for Florida residents 33127-0200 • 305-694-6210 the poor die H.E. SIGISMUND REEVES Founder, 1923-1968 no person, the Black Press strives to GARTH C. REEVES JR. Editor, 1972-1982 help every person in the firm belief that ith President Trump’s impeachment hearing domi- GARTH C. REEVES SR. -

Wonderful! 143: Rare, Exclusive Gak Published July 29Th, 2020 Listen on Themcelroy.Family

Wonderful! 143: Rare, Exclusive Gak Published July 29th, 2020 Listen on TheMcElroy.family [theme music plays] Rachel: I'm gonna get so sweaty in here. Griffin: Are you? Rachel: It is… hotototot. Griffin: Okay. Is this the show? Are we in it? Rachel: Hi, this is Rachel McElroy! Griffin: Hi, this is Griffin McElroy. Rachel: And this is Wonderful! Griffin: It‘s gettin‘ sweaaatyyy! Rachel: [laughs] Griffin: It‘s not—it doesn‘t feel that bad to me. Rachel: See, you're used to it. Griffin: Y'know what it was? Mm, I had my big fat gaming rig pumping out pixels and frames. Comin‘ at me hot and heavy. Master Chief was there. Just so fuckin‘—just poundin‘ out the bad guys, and it was getting hot and sweaty in here. So I apologize. Rachel: Griffin has a very sparse office that has 700 pieces of electronic equipment in it. Griffin: True. So then, one might actually argue it‘s not sparse at all. In fact, it is filled with electronic equipment. Yeah, that‘s true. I imagine if I get the PC running, I imagine if I get the 3D printer running, all at the same time, it‘s just gonna—it could be a sweat lodge. I could go on a real journey in here. But I don‘t think it‘s that bad, and we‘re only in here for a little bit, so let‘s… Rachel: And I will also say that a lot of these electronics help you make a better podcast, which… is a timely thing. -

Inventory of American Sheet Music (1844-1949)

University of Dubuque / Charles C. Myers Library INVENTORY OF AMERICAN SHEET MUSIC (1844 – 1949) May 17, 2004 Introduction The Charles C. Myers Library at the University of Dubuque has a collection of 573 pieces of American sheet music (of which 17 are incomplete) housed in Special Collections and stored in acid free folders and boxes. The collection is organized in three categories: African American Music, Military Songs, and Popular Songs. There is also a bound volume of sheet music and a set of The Etude Music Magazine (32 items from 1932-1945). The African American music, consisting of 28 pieces, includes a number of selections from black minstrel shows such as “Richards and Pringle’s Famous Georgia Minstrels Songster and Musical Album” and “Lovin’ Sam (The Sheik of Alabami)”. There are also pieces of Dixieland and plantation music including “The Cotton Field Dance” and “Massa’s in the Cold Ground”. There are a few pieces of Jazz music and one Negro lullaby. The group of Military Songs contains 148 pieces of music, particularly songs from World War I and World War II. Different branches of the military are represented with such pieces as “The Army Air Corps”, “Bell Bottom Trousers”, and “G. I. Jive”. A few of the delightful titles in the Military Songs group include, “Belgium Dry Your Tears”, “Don’t Forget the Salvation Army (My Doughnut Girl)”, “General Pershing Will Cross the Rhine (Just Like Washington Crossed the Delaware)”, and “Hello Central! Give Me No Man’s Land”. There are also well known titles including “I’ll Be Home For Christmas (If Only In my Dreams)”. -

Offical File-Christmas Songs

1 The History and Origin of Christmas Music (Carol: French = dancing around in a circle.) Table of Contents Preface 3 Most Performed Christmas Songs 4 The Christmas Song 5 White Christmas 5 Santa Claus is Coming to Town 6 Winter Wonderland 7 Have Yourself a Merry Christmas 8 Sleigh Ride 9 Rudolph the Red Nosed Reindeer 10 My Two Front Teeth 11 Blue Christmas 11 Little Drummer Boy 11 Here Comes Santa Claus 12 Frosty the Snowman 13 Jingle Bells 13 Let it Snow 15 I’ll Be Home for Christmas 15 Silver Bells 17 Beginning to Look Like Christmas 18 Jingle Bell Rock 18 Rockin’ Round Christmas Tree 19 Up on the Housetop 19 Religious Carols Silent Night 20 O Holy Night 22 O Come All Ye Faithful 24 How firm A Foundation 26 Angels We Have Heard on High 27 O Come Emmanuel 28 We Three Kings 30 It Came Upon a Midnight Clear 31 Hark the Herald Angels Sing 33 The First Noel 34 The 12 Days of Christmas 36 God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen 36 Lo How A Rose E’er Blooming 39 Joy to the World 39 Away in a Manger 41 O Little Town of Bethlehem 44 Coventry Carol 46 2 Good King Wenceslas 46 I Saw Three Ships 48 Greensleeves 49 I Heard the Bells/Christmas Day 50 Deck the Hall 52 Carol of the Bells 53 Do You Hear What I Hear 55 Birthday of a King 56 Wassil Song 57 Go Tell it on the Mountain 58 O Tannanbaum 59 Holly and the Ivy 60 Echo Carol 61 Wish You a Merry Christmas 62 Ding Dong Merrily Along 63 I Wonder as I Wander 64 Patapatapan 65 While Shepherds Watch Their Flocks by Night 66 Auld Lang Syne 68 Over the River, thru the Woods 68 Wonderful time of the Year 70 A Little Boy Came to Bethlehem To Bethlehem Town 70 Appendix I (Jewish composers Of Holiday Music 72 Preface In their earliest beginning the early carols had nothing to do with Christmas or the Holiday season. -

2011 Holiday Concert

Old Dominion University Department of Music____________ Presents 2011 Holiday Concert Old Dominion University Wind Ensemble Director, Dennis Zeisler Old Dominion University Madrigal Singers Director, Lee Teply Old Dominion University Symphony Orchestra Director, Lucy Manning Diehn Fine and Performing Arts Atrium December 11, 2011 3:00pm Program Wind Ensemble Piccolo Bass Clarinet Trombone I Wind Ensemble Jenna Henkel Ryan Cabels Tuhin Mukherjee Roscoe Schieler Ukrainian Bell Carol Arr. Morgan Hatfield Flute I Contra-Bass Clarinet Rebecca McMahan Ryan Collins Trombone II Christmas Music From Bach J.S. Bach Heather Yoon Rawn Boulden - from the Christmas Oratorio Arr. Frank Erickson Alto Saxophone Jack Himmelman I. Come and Praise Him Flute II Wayne Ray II. Holy Child Tim Minter Chris Byrd Bass Trombone III. Be Joyful Katherine Moore Greg Hausmann Tenor Saxophone Oboe Lewis Hundley Euphonium Alexandra Borza - Graduate Conductor Karl Stolte Pete Echols Lance Irons Baritone Saxophone Jared Raymer The Eighth Candle Steve Reisteter Phil Rosi Kerschal Santa Maria Bassoon Prayer and Dance for Hanukkah Ed Taylor Tuba Keith Stolte Cornet I Andrew Bohnert Lewis Hundley - Graduate Conductor Dylan Carson Bruce Lord Clarinet I Christian Van Deven Lance Schade Festive Songs of Christmas Arr. Frank Erickson Andre Jefferson Jr. Steve Wilkins Barron Maskew Meagan Armstrong Carlos Saenz - Graduate Conductor John Presto Cornet II Percussion Lexi Borza Chris Vollhardt Sarah Williams Jordan DiCaprio Maegan Rowley Russian Christmas Music Alfred Reed Clarinet II Elizabeth Smith Dennis Northerner Jimin Kim Amber Hentley Madrigal Singers Aryles Hedjar Cornet III Chad Murray Chris Monteith Carlos Saenz Gloucestershire Wassail Arr. Ralph Vaughan Williams Sarah Bass Jasmine Bland Piano Charles Winstead John Presto God Rest You Merry, Gentlemen Arr. -

Running Head: in SEARCH of MULTICULTURAL WORKS for WIND BAND 1

Running Head: IN SEARCH OF MULTICULTURAL WORKS FOR WIND BAND 1 IN SEARCH OF MULTICULTURAL WORKS FOR WIND BAND BY ROBERT PERKINS SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: DR. TERESE TUOHEY, CHAIR DR. MATTHEW THIBEAULT, MEMBER A PROJECT IN LIEU OF THESIS PRESENTED TO THE COLLEGE OF THE ARTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF MUSIC UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2015 IN SEARCH OF MULTICULTURAL WORKS FOR WIND BAND 2 Abstract In 1990 MENC hosted a symposium on multicultural music education in our nation, with a charge to be more musically inclusive in our classrooms. Since then, general music and choral classrooms have experienced a large expansion of multicultural musics into their curriculum. In reading state contests lists, attending concerts, and reviewing suggested repertoire lists, the wind band continues to lag behind in diverse, multicultural programming. Either wind bands remain content with the music of Percy Grainger, which is very authentic, or allow good pieces like Russian Christmas Music, Variations on a Korean Folk Song, and La Fiesta Mexicana to continue to be the cornerstone of the wind band’s multicultural literature, despite these pieces being in the western art music style and having very limited efforts to substitute culturally appropriate instruments and forms. Bands appear to be content with “war horse” repertoire of limited authenticity and are not branching out. In 1998 Dr. Terese Volk published four categories to determine the cultural authenticity of a piece of music. This project will present a catalog of twenty-five works for wind band that meet her parameters for the two categories with the most authenticity, Category 3 and Category 4. -

Life Writing Prize 2021

Life Writing Prize 2021 Longlist Anthology Life Writing Prize 2021 Longlist Anthology The Life Writing Prize has been made possible thanks to a generous donation by Joanna Munro. We’d also like to thank the Goldsmiths Writers’ Centre for their partnership on the Prize. First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Spread the Word. Copyright © remains with the authors. All rights reserved. CONTENTS Foreword 5 Santanu Bhattacharya The Nicer One* 8 Carla Jenkins Carving 21 Matt Taylor Tromode House 36 Sara Doctors Grief Bacon 46 SJ Lyon People That Might Be Us 61 Lois Warner White Lines* 68 Nic Wilson By The Wayside 81 Laura McDonagh Commonplace 94 Penny Kiley How To Watch Your Mother Die 108 Imogen Phillips Taken and Left* 119 Susan Daniels The Secret* 136 Pete Williams The Strawbs 143 Acknowledgements 158 About Spread the Word 159 *Trigger warning: these stories include references to sexual assault, violence, rape and child sex abuse. FOREWORD The Spread the Word Life Writing Prize, in association with Goldsmiths Writers’ Centre, is now in its fifth year. The twelve pieces featured in this anthology form the longlist selected from over 900 entries sent in from across the UK. In a challenging year they are proof that life writing is thriving. As with last year, the judging took place virtually with Catherine Cho, Damian Barr and Frances Wilson deliberating to pick a shortlist of six, followed by two highly commended entries and one winner. The winner of the Life Writing Prize 2021 is The Nicer One by Santanu Bhattacharya, a piece that mixes the familiar experience of bumping into a childhood classmate at a party with a harrowing retelling of schoolboy abuse. -

My Way: a Musical Tribute to Frank Sinatra

Otterbein University Digital Commons @ Otterbein 2008 Summer Theatre Productions 2001-2010 8-1-2008 My Way: A Musical Tribute to Frank Sinatra Otterbein University Theatre and Dance Department Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/summer_production_2008 Part of the Acting Commons, Dance Commons, and the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Otterbein University Theatre and Dance Department, "My Way: A Musical Tribute to Frank Sinatra" (2008). 2008 Summer Theatre. 1. https://digitalcommons.otterbein.edu/summer_production_2008/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Productions 2001-2010 at Digital Commons @ Otterbein. It has been accepted for inclusion in 2008 Summer Theatre by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Otterbein. For more information, please contact [email protected]. My Way A Musical Tribute to Frank Sinatra Conceived by David Grapes & Todd Olson Book by Todd Olson Original Production Directed by David Grapes Original piano/vocal arrangements by Vince di Mura Additional arrangements by Stephen Kummer and Donald Jenzcka Score conception and interpretive consultant Vince di Mura First workshop production presented at Artpark at the Church, Lewiston, NY- May, 1999 World Premiere at Tennessee Repertory Theatre, Nashville, TN - July, 2000 Audio Clips Designed by Ryan C. Mansfield Direction and Musical Staging by David Caldwcll Music Direction by Dennis DaVCnpOrt Scenic Design by Stephanie Gerckens Costume Design by Marcia Hain Lighting Design by Andy Baker Sound Design by Laura Fickley Featuring Tina Scariano Elizabeth Shivener Lucas Dixon Cory Smith Dennis Davenport, keyboard David White, bass Tomasz Jarzecki, drums Presented by arrangement with Summerwind Productions, PO Box 430, Windsor, CO 80550. -

Publication Management, Content Strategy & Execution Specialty Writing Production & Consulting

Content Strategy & Execution Content Strategy 843.513.7535 ~ [email protected] riverbendcustomcontent.com Professional Profile Respected leader of creative teams with proven ability to conceptualize and orchestrate communications campaigns that effectively build and reinforce brand. Collaborative team player adept at transforming complex ideas and subject matter into digestible information that connects, enlightens and engages target markets and segments. Select Professional Achievements Established and executed a content/thought leadership communications program to enhance the Elliott Davis brand and strengthen the firm’s position as a diversified business solutions provider offering a full spectrum of professional financial services and consulting. Content Strategy Created and directed the National Golf Course Owners Association’s first Comprehensive In conjunction with CMO and Content Strategy, a three-phase, multi-year plan that established the four pillars under marketing director, developed a which all NGCOA educational content was categorized and developed. comprehensive plan and editorial calendar to create, schedule and Spearheaded two complete repositionings of Golf Business magazine, re-establishing the deliver content and collateral for title as the golf industry’s preeminent business publication. all Elliott Davis business units. Garnered multiple awards for writing and publication excellence from the Society of National Association Publications, Turf & Ornamental Communications Association, International Network of Golf and Carolinas Golf Reporters Association. Areas of Specialty & Expertise Editorial, Creative & Publication Management, Content Strategy & Execution Specialty Writing Production & Consulting Experienced professional Award-winning writer whose Veteran, award-winning skilled in the development articles and columns have magazine editor with more and creation of content, appeared in numerous national, than two decades of experience educational curricula and regional and local publications. -

"A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 Piano Solo | Twelfth 12Th Street Rag 1914 Euday L

Box Title Year Lyricist if known Composer if known Creator3 Notes # "A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 piano solo | Twelfth 12th Street Rag 1914 Euday L. Bowman Street Rag 1 3rd Man Theme, The (The Harry Lime piano solo | The Theme) 1949 Anton Karas Third Man 1 A, E, I, O, U: The Dance Step Language Song 1937 Louis Vecchio 1 Aba Daba Honeymoon, The 1914 Arthur Fields Walter Donovan 1 Abide With Me 1901 John Wiegand 1 Abilene 1963 John D. Loudermilk Lester Brown 1 About a Quarter to Nine 1935 Al Dubin Harry Warren 1 About Face 1948 Sam Lerner Gerald Marks 1 Abraham 1931 Bob MacGimsey 1 Abraham 1942 Irving Berlin 1 Abraham, Martin and John 1968 Dick Holler 1 Absence Makes the Heart Grow Fonder (For Somebody Else) 1929 Lewis Harry Warren Young 1 Absent 1927 John W. Metcalf 1 Acabaste! (Bolero-Son) 1944 Al Stewart Anselmo Sacasas Castro Valencia Jose Pafumy 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Accidents Will Happen 1950 Johnny Burke James Van Huesen 1 According to the Moonlight 1935 Jack Yellen Joseph Meyer Herb Magidson 1 Ace In the Hole, The 1909 James Dempsey George Mitchell 1 Acquaint Now Thyself With Him 1960 Michael Head 1 Acres of Diamonds 1959 Arthur Smith 1 Across the Alley From the Alamo 1947 Joe Greene 1 Across the Blue Aegean Sea 1935 Anna Moody Gena Branscombe 1 Across the Bridge of Dreams 1927 Gus Kahn Joe Burke 1 Across the Wide Missouri (A-Roll A-Roll A-Ree) 1951 Ervin Drake Jimmy Shirl 1 Adele 1913 Paul Herve Jean Briquet Edward Paulton Adolph Philipp 1 Adeste Fideles (Portuguese Hymn) 1901 Jas. -

Variants Concert Band and Wind Ensemble

SCHOOL OF MUSIC VARIANTS CONCERT BAND AND WIND ENSEMBLE Gerard Morris, conductor Laura Erskine ’12, M.A.T.’13, practicum assistant conductor Friday, Nov. 30, 2012 • 7:30 p.m. • Schneebeck Concert Hall University of Puget Sound • Tacoma, WA PROGRAM CONCERT BAND Kirkpatrick Fanfare ..................................................................Andrew Boysen Jr. b. 1968 Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring ......................................................................J.S. Bach (1685–1750) arr. by Lucien Cailliet English Folk Song Suite ..................................................Ralph Vaughn Williams I. March “Seventeen Come Sunday” (1872–1958) II. Intermezzo “My Bonny Boy” III. March “Folk Songs from Somerset” Laura Erskine, practicum assistant conductor Russian Christmas Music ...................................................................Alfred Reed (1921–2005) INTERMISSION WIND ENSEMBLE March, Opus 99 ............................................................................Serge Prokofieff (1891–1953) Symphony No. 8 in D Minor ........................................Ralph Vaughan Williams II. Scherzo alla Marcia Variants on a Medieval Tune ................................................. Norman Dello Joio Theme: In dulci jubilo (1913–2008) Variant I: Allegro deciso Variant II: Lento Variant III: Allegro spumante Variant IV: Andante Variant V: Allegro gioioso As a courtesy to the performers and fellow audience members, please take a moment to turn off all beepers on watches, pagers, and cell phones. Flash photography is