The Murder of Vincent Chin*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reenactment Program

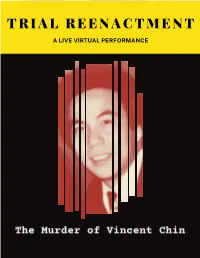

T R I A L R E E N A C T M E N T A LIVE VIRTUAL PERFORMANCE The Asian Pacific American Bar Association of South Florida WITH ITS COHOSTS The Asian Pacific American Bar Association of Tampa Bay The Greater Orlando Asian American Bar Association The Jacksonville Asian American Bar Association PRESENT THE MURDER OF VINCENT CHIN ORIGINAL SCRIPT BY THE ASIAN AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION OF NEW YORK VISUALS BY JURYGROUP TECHNOLOGY SUPPORT BY GREENBERG TRAURIG, PA WITH MARIA AGUILA ONCHANTHO AM VANESSA L. CHEN BENJAMIN W. DOWERS ZARRA ELIAS TIMOTHY FERGUSON JACQUELINE GARDNER ALLYN GINNS AYERS E.J. HUBBS JAY KIM GREG MAASWINKEL MELISSA LEE MAZZITELLI GUY KAMEALOHA NOA ALICE SUM AND THE HONORABLE JEANETTE BIGNEY THE HONORABLE HOPE THAI CANNON THE HONORABLE ANURAAG SINGHAL ARTISTIC DIRECTION BY DIRECTED BY PRODUCED BY ALLYN GINNS AYERS BERNICE LEE SANDY CHIU ABOUT APABA SOUTH FLORIDA The Asian Pacific American Bar Association of South Florida (APABA) is a non-profit, voluntary bar organization of attorneys in Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach counties who support APABA’s objectives and are dedicated to ensuring that minority communities are effectively represented in South Florida. APABA of South Florida is an affiliate of the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association (“NAPABA”). All members of APABA are also members of NAPABA. APABA’s goals and objectives coincide with those of NAPABA, including working towards civil rights reform, combating anti-immigrant agendas and hate crimes, increasing diversity in federal, state, and local government, and promoting professional development. The overriding mission of APABA is to combat discrimination against all minorities and to promote diversity in the legal profession. -

Dreaming in Black and White: Racial-Sexual Policing in the Birth of a Nation, the Cheat, and Who Killed Vincent Chin?

Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons Faculty Scholarship 1-1-1998 Dreaming in Black and White: Racial-Sexual Policing in The Birth of a Nation, The Cheat, and Who Killed Vincent Chin? Robert S. Chang Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/faculty Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Robert S. Chang, Dreaming in Black and White: Racial-Sexual Policing in The Birth of a Nation, The Cheat, and Who Killed Vincent Chin?, 5 ASIAN L.J. 41 (1998). https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/faculty/407 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dreaming in Black and White: Racial- Sexual Policing in The Birth of a Nation, The Cheat, and Who Killed Vincent Chin? Robert S. Changt Professor Chang observes that Asians are often perceived as interlopers in the nativistic American "family." This conception of a nativist 'fam- ily" is White in composition and therefore accords a sense of economic and sexual entitlement to Whites, ironically, even ifparticular benefici- aries are recent immigrants. Transgressions by those perceived to be "illegitimate," such as Asians and Blacks, are policed either by rule of law or the force of sanctioned vigilante violence. Chang illustrates his thesis by drawing upon the threefilms referenced Introduction ............................................................................................42 I. Policing the Family that Is "America": Racial-Sexual Policing in The Birth of a Nation and The Cheat ......................................45 A. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Asian

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Asian American and African American Masculinities: Race, Citizenship, and Culture in Post -Civil Rights A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Phil osophy in Literature by Chong Chon-Smith Committee in charge: Professor Lisa Lowe, Chair Professor Takashi Fujitani Professor Judith Halberstam Professor Nayan Shah Professor Shelley Streeby Professor Lisa Yoneyama This dissertation of Chong Chon-Smith is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2006 iii DEDICATION I have had the extraordinary privilege and opportunity to learn from brilliant and committed scholars at UCSD. This dissertation would not have been successful if not for their intellectual rigor, wisdom, and generosity. This dissertation was just a dim thought until Judith Halberstam powered it with her unique and indelible iridescence. Nayan Shah and Shelley Streeby have shown me the best kind of work American Studies has to offer. Their formidable ideas have helped shape these pages. Tak Fujitani and Lisa Yoneyama have always offered me their time and office hospitality whenever I needed critical feedback. -

The Immigrant and Asian American Politics of Visibility

ANXIETIES OF THE FICTIVE: THE IMMIGRANT AND ASIAN AMERICAN POLITICS OF VISIBILITY A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY SOYOUNG SONJIA HYON IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY RODERICK A. FERGUSON JOSEPHINE D. LEE ADVISERS JUNE 2011 © Soyoung Sonjia Hyon 2011 All Rights Reserved i Acknowledgements There are many collaborators to this dissertation. These are only some of them. My co-advisers Roderick Ferguson and Josephine Lee mentored me into intellectual maturity. Rod provided the narrative arc that structures this dissertation a long time ago and alleviated my anxieties of disciplinarity. He encouraged me to think of scholarship as an enjoyable practice and livelihood. Jo nudged me to focus on the things that made me curious and were fun. Her unflappable spirit was nourishing and provided a path to the finishing line. Karen Ho’s graduate seminar taught me a new language and framework to think through discourses of power that was foundational to my project. Her incisive insights always push my thinking to new grounds. The legends around Jigna Desai’s generosity and productive feedback proved true, and I am lucky to have her on my committee. The administrative staff and faculty in American Studies and Asian American Studies at the University of Minnesota have always been very patient and good to me. I recognize their efforts to tame unruly and manic graduate students like myself. I especially thank Melanie Steinman for her administrative prowess and generous spirit. Funding from the American Studies Department and the Leonard Memorial Film Fellowship supported this dissertation. -

April 29-Neal-Rubin-Cache

April 29, 2014 at 12:22 pm What we all assume we know about the Vincent Chin case probably isn't so Neal Rubin From The Detroit News: http://www.detroitnews.com/article/20140429/METRO08/304290025#ixzz30O2DdcKl Two unemployed autoworkers beat Vincent Chin to death because they thought he was Japanese and they drunkenly decided he had cost them their jobs. That’s an accepted piece of history, like Ty Cobb being the worst racist in baseball or Henry Ford boosting his workers’ daily wage to $5 so they could buy his cars. It popped up again last week in the New York Times, in a piece about the mob attack on tree trimmer Steve Utash. “I remember two out-of-work white autoworkers in 1982,” the article says, “beating a Chinese-American man to death because they thought he was Japanese.” The problem, says Tim Kiska, is that “almost all of that is wrong.” Chin was, in fact, murdered. The killers were two white men, and it has never made sense that they didn’t go to jail. Neither was unemployed, however, one worked for a furniture chain, and the only testimony connecting the crime to fury over the auto industry was so dubious that a jury in a federal civil rights trial rejected it. The early ’80s was an angry time, with Japanese car companies thriving while the Big Three stumbled. A bar Downriver bought a sledgehammer and a junked Toyota, and people lined up to take their whacks. The Chin story has context, drama and outrage. But sometimes, the accepted truth shouldn’t be. -

UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Asian American and African American masculinities : race, citizenship, and culture in post- civil rights Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0c8255gj Author Chon-Smith, Chong Publication Date 2006 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Asian American and African American Masculinities: Race, Citizenship, and Culture in Post -Civil Rights A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Phil osophy in Literature by Chong Chon-Smith Committee in charge: Professor Lisa Lowe, Chair Professor Takashi Fujitani Professor Judith Halberstam Professor Nayan Shah Professor Shelley Streeby Professor Lisa Yoneyama This dissertation of Chong Chon-Smith is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2006 iii DEDICATION I have had the extraordinary privilege and opportunity to learn from brilliant and committed scholars at UCSD. This dissertation would not have been successful if not for their intellectual rigor, wisdom, and generosity. This dissertation was just a dim thought until Judith Halberstam powered it with her unique and indelible iridescence. Nayan Shah and Shelley Streeby have shown me the best kind of work American Studies has to offer. Their formidable ideas have helped shape these pages. Tak Fujitani and Lisa Yoneyama have always offered me their time and office hospitality whenever I needed critical feedback. I want to thank them for their precise questions and open door. -

Casco Bay Weekly : 15 February 1990

Portland Public Library Portland Public Library Digital Commons Casco Bay Weekly (1990) Casco Bay Weekly 2-15-1990 Casco Bay Weekly : 15 February 1990 Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.portlandlibrary.com/cbw_1990 Recommended Citation "Casco Bay Weekly : 15 February 1990" (1990). Casco Bay Weekly (1990). 5. http://digitalcommons.portlandlibrary.com/cbw_1990/5 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Casco Bay Weekly at Portland Public Library Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Casco Bay Weekly (1990) by an authorized administrator of Portland Public Library Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. osc Greater Portland's news and arts weekly FEBRUARY 15, 1990 FlEE Healthy faces, hidden wounds By Andy Newman removed and a metal plate was put in her head. The scar Those consequences are not as obvious as mouths that is hidden beneath her hair. don't talk right, eyes that don't see right, limbs twisted "I'm not the type of person who 'shoplifts. I never According to the National Head Injury Foundation in a spasm. But to Corinne and the people that advo did that kind of thing before my accident," said Corinne. (NHIF), an injury to the brain can paralyze someone as cate for her, those hidden disabilities are just as real as But Corinne recently risked spending60days in jail well as impairing speech, vision and hearing. Those are the more visible ones. They claim Corinne's disabili when she entered Shop 'n Save - a store her probation the apparent effects of head injury. -

July 7, 1983 O&E {T,Ro-8B,S,F-10B,LJP,C-5B.R,VV.Q-6B)**11C Ann Arbor's Place Has an Old World Flair

it v m , / * All-stars kick way into soccer classic ie 4_» 'j-*.- »y <c-—. Volume 19 Number 4 .Thursday,* July; 7,1983 Westland, Michigan 44Pages_ Twenty-Five Cents <-1MJ $4^.^^0,.^^10,^0^.110.: AJl'fftftu'^r'.rf sees video tapes closing 2 city in Westlandl judgeVtrial ByMaryKlamlc stations ataff writer By 8andra Armbruster was made because the council elimi A videotape of 18 th District Judge editor nated two pipemen from my proposed Evan Callanan Sr. and an FBItnform- budget and.reduced an assistant fire ant allegedly counting out $1,500 In a All four- Westland fire stations will chief," he said. "As a result, there is ^ car was played to Jurors Wednesday as remain open, at least temporarily. less personnel'to man the stations, and ^4^¾^^^^¾ the trtalofthe judge and three other- Tuesday night the city council unani-- there are definite re^tiTctiom^M-the-^^?^^^, men continued. ^ mousry approved a resolution prohibit budget not to Increase overtime to *'--^--^-^¾^ Callanan and fellow defendants Evan ing, the mayor from closing one station. maintain the staff." Callanan Jr. — the judge's son — BJch- Mayor,Charles Pickering, following , Pickering,added that a.decision to ..ard\ Debs and Sam Qaoud were also a recommendation from Fire Chief Ted eliminate the assistant fire chief's pos- heard-Wednesday In recorded-conyer- Scott, had proposed closing a station tlon, responsible for training,.would satto.ns that'were played in court. • when the staffing level dropped below. "force us to'go outside to recertify The conversations were with the gox.-_ • a minimum of 15 people. -

Vincent Chin</Em>

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 1 1996 The Social Construction of Identity in Criminal Cases: Cinema Verité and the Pedagogy of Vincent Chin Paula C. Johnson Syracuse University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Criminal Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Recommended Citation Paula C. Johnson, The Social Construction of Identity in Criminal Cases: Cinema Verité and the Pedagogy of Vincent Chin, 1 MICH. J. RACE & L. 347 (1996). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol1/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF IDENTITY IN CRIMINAL CASES: CINEMA VERrT AND THE PEDAGOGY OF VINCENT CHIN Paula C. Johnson* IN TRO D U CTIO N ................................................................................... 348 I. THE ENIGMA OF RACE ........................................................................... 355 A . Theories of Racial Identity ............................................................. 355 1. Biological R ace ......................................................................... 355 2. Socially Constructed Race ..................................................... -

Who Killed Vincent Chin? (1988): Ethnicity and a Babble of Discourses LESLIE FISHBEIN

Who Killed Vincent Chin? (1988): Ethnicity and a Babble of Discourses LESLIE FISHBEIN Who killed Vincent Chin? A film by Christine Choy and Renee Tajima New York, New York: Filmakers Library [distributor] 124 East 40th Street, New York, New York 10016. Telephone: (212) 8084980; FAX (212) 808-4983. 1988. 1 videocassette (82 minutes); sound; color; 1/2 inch. Credits: edited by Holly FIsher; produced by Renee Tajima. Summary This Academy Award-nominated : film related the brutal murder of 27- year-old Vincent Chin in a Detroit bar [sic]. Outraged at the suspended sentence that was given Ron Ebens, who bludgeoned Chin to death, the Asian-American community organized an unprecedented civil rights protest to successfully bring Ebens up for retrial. Popular wisdom would have us dismiss the building of the Tower of Babel as an instance of divine punishment for human hubris, the tragic sin of pride represented by the belief that mankind could elevate itself closer to heaven through its own efforts. God punished mankind by scattering it across the earth and dividing it by a babble of languages that would prove mutually incomprehensible and prevent mankind from ever uniting again in such a prideful project. However, rabbinical authorities have been kinder in their interpretation of this biblical episode, noting that those who built the Tower of Babel were impelled by their love of God and their desire to grow closer to Him and that their tragic mistake derived from their naivete and from their desire for a unanimity of purpose that was suspect in divine eyes rather than from a more venial motive. -

The History of West Deer Township

Allegheny County, Pennsylvania West Deer Township 150 years of History as told by those that lived here a updated look. (rev 1) ______________________________________________________________________________________________ Copyright 2004 ______________________________________________________________________________________________ Notes regarding the publishing of this book. First let me introduce myself. My name is Ken Lewetag son of Ernest Lee Lewetag (a miner) and Victoria Baron (worked at Palmers and delivered milk from the "Barons" in Superior). My Grandfathers (Ernest J Lewetag and Stanislaw "Stine" Baron) were both miners as was their fathers. I was born in 1954 and lived in Russellton until 1965 when I moved to Oregon. I have always called West Deer my home and have remembered it fondly. My mother received a copy of WEST DEER TOWNSHIP A CENTURY AND A HALF OF PROGRESS 1836-1986 from a relative in West Deer. In 1999 I began to research my roots and found this book and read it cover to cover. In March 2004 after many attempts I finally was able to contact Mrs. Dorothy Voeckel and Mrs. Ruth Graff the only remaining authors of that book. I explained that I would like to use their book in part for a new book that would be publish in an electronic form and possible in a printed form, which received their blessing The reason for this publishing, printing and electronic publication is that so few copies of WD150 are available to libraries and schools to research and learn about the coal mining regions of Pennsylvania; specifically of my hometown Russellton and those of my family in Superior and Curtisville. In addition major omissions on the mines within WD150 and needed to be included. -

A New Kind of Justice Plymouth* Ml

'Plymouth District Library • 223 S. Main Street BY ALEX LUNDBERG to the streets, explained the general plans for the The primary goal of the plan is to “make a flexible If planners get their way, downtown Plymouth will be operation. streetscape; one thait can adapt to changing conditions,” porting new sidewalks, planters and other street The design and construction budget for the project is Vogel said. nprovements — totalling $1.8 million — by this fall. $1.8 million with possible additions and deletions According to the plan, all streets in the downtown area That was the idea presented at last Thursday’s meeting forthcoming. will be affected. f the Plymouth Downtown Development Authority. One of those additions likely to be implemented are the Part of the plans calls for paving bricks to be installed Leading the presentation of the so-called “streetscape” replacement of the existing Detroit Edison poles with a between the curb and the sidewalk. The bricks would be lan were Steve Guile, director of Plymouth’s DDA, and new lighting system and buried lines. arranged in a belt 3-feet-4-inehes wide. teve Vogel, representing the architectural firm of Vogel stated that the three main concerns were street Other streets will have different brick patterns and chervish Vogel Merz. furniture, refurbishing the lighting and changes in the dimensions. Wing Sitreet will not have any paving bricks. Vogel, whose company will handle the changes made paving of the sidewalks. Please see pg. 2 B Plymouth District Library 223 S. Main. Street Man faces A new kind of justice Plymouth* Ml.