UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reenactment Program

T R I A L R E E N A C T M E N T A LIVE VIRTUAL PERFORMANCE The Asian Pacific American Bar Association of South Florida WITH ITS COHOSTS The Asian Pacific American Bar Association of Tampa Bay The Greater Orlando Asian American Bar Association The Jacksonville Asian American Bar Association PRESENT THE MURDER OF VINCENT CHIN ORIGINAL SCRIPT BY THE ASIAN AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION OF NEW YORK VISUALS BY JURYGROUP TECHNOLOGY SUPPORT BY GREENBERG TRAURIG, PA WITH MARIA AGUILA ONCHANTHO AM VANESSA L. CHEN BENJAMIN W. DOWERS ZARRA ELIAS TIMOTHY FERGUSON JACQUELINE GARDNER ALLYN GINNS AYERS E.J. HUBBS JAY KIM GREG MAASWINKEL MELISSA LEE MAZZITELLI GUY KAMEALOHA NOA ALICE SUM AND THE HONORABLE JEANETTE BIGNEY THE HONORABLE HOPE THAI CANNON THE HONORABLE ANURAAG SINGHAL ARTISTIC DIRECTION BY DIRECTED BY PRODUCED BY ALLYN GINNS AYERS BERNICE LEE SANDY CHIU ABOUT APABA SOUTH FLORIDA The Asian Pacific American Bar Association of South Florida (APABA) is a non-profit, voluntary bar organization of attorneys in Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach counties who support APABA’s objectives and are dedicated to ensuring that minority communities are effectively represented in South Florida. APABA of South Florida is an affiliate of the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association (“NAPABA”). All members of APABA are also members of NAPABA. APABA’s goals and objectives coincide with those of NAPABA, including working towards civil rights reform, combating anti-immigrant agendas and hate crimes, increasing diversity in federal, state, and local government, and promoting professional development. The overriding mission of APABA is to combat discrimination against all minorities and to promote diversity in the legal profession. -

Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma

Michigan Journal of Race and Law Volume 18 2012 Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma Hosea H. Harvey Temple University, James E. Beasley School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl Part of the Antitrust and Trade Regulation Commons, Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Hosea H. Harvey, Race, Markets, and Hollywood's Perpetual Antitrust Dilemma, 18 MICH. J. RACE & L. 1 (2012). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol18/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of Race and Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RACE, MARKETS, AND HOLLYWOOD'S PERPETUAL ANTITRUST DILEMMA Hosea H. Harvey* This Article focuses on the oft-neglected intersection of racially skewed outcomes and anti-competitive markets. Through historical, contextual, and empirical analysis, the Article describes the state of Hollywood motion-picture distributionfrom its anti- competitive beginnings through the industry's role in creating an anti-competitive, racially divided market at the end of the last century. The Article's evidence suggests that race-based inefficiencies have plagued the film distribution process and such inefficiencies might likely be caused by the anti-competitive structure of the market itself, and not merely by overt or intentional racial-discrimination.After explaining why traditional anti-discrimination laws are ineffective remedies for such inefficiencies, the Article asks whether antitrust remedies and market mechanisms mght provide more robust solutions. -

The Rules of #Metoo

University of Chicago Legal Forum Volume 2019 Article 3 2019 The Rules of #MeToo Jessica A. Clarke Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Clarke, Jessica A. (2019) "The Rules of #MeToo," University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 2019 , Article 3. Available at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol2019/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Chicago Legal Forum by an authorized editor of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Rules of #MeToo Jessica A. Clarke† ABSTRACT Two revelations are central to the meaning of the #MeToo movement. First, sexual harassment and assault are ubiquitous. And second, traditional legal procedures have failed to redress these problems. In the absence of effective formal legal pro- cedures, a set of ad hoc processes have emerged for managing claims of sexual har- assment and assault against persons in high-level positions in business, media, and government. This Article sketches out the features of this informal process, in which journalists expose misconduct and employers, voters, audiences, consumers, or professional organizations are called upon to remove the accused from a position of power. Although this process exists largely in the shadow of the law, it has at- tracted criticisms in a legal register. President Trump tapped into a vein of popular backlash against the #MeToo movement in arguing that it is “a very scary time for young men in America” because “somebody could accuse you of something and you’re automatically guilty.” Yet this is not an apt characterization of #MeToo’s paradigm cases. -

THE LAST SEX: FEMINISM and OUTLAW BODIES 1 Arthur and Marilouise Kroker

The Last Sex feminism and outlaw bodies CultureTexts Arthur and Marilouise Kroker General Editors CultureTexts is a series of creative explorations of the theory, politics and culture of postmodem society. Thematically focussed around kky theoreti- cal debates in areas ranging from feminism and technology to,social and political thought CultureTexts books represent the forward breaking-edge of contempory theory and prac:tice. Titles The Last Sex: Feminism and Outlnw Bodies edited and introduced by Arthur and Marilouise Kroker Spasm: Virtual Reality, Android Music and Electric Flesh Arthur Kroker Seduction Jean Baudrillard Death cE.tthe Parasite Cafe Stephen Pfohl The Possessed Individual: Technology and the French Postmodern Arthur Kroker The Postmodern Scene: Excremental Culture and Hyper-Aesthetics Arthur Kroker and David Cook The Hysterical Mule: New Feminist Theory edited and introduced by Arthur-and Marilouise Kroker Ideology and Power in the Age of Lenin in Ruins edited and introduced by Arthur and Marilouise Kroker , Panic Encyclopedia Arthur Kroker, Maril.ouise Kroker and David Cook Life After Postmodernism: Essays on Value and Culture edited and intloduced by John Fekete Body Invaders edited and introduced by Arthur and Marilouise Kroker THE LAST SEX feminism and outlaw bodies Edited with an introduction by Arthur and Marilouise Kroker New World Perspectives CultureTexts Series Mont&al @ Copyright 1993 New World Perspectives CultureTexts Series All rights reserved. No part of this publication may he reproduced, stored in o retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without prior permission of New World Perspectives. New World Perspectives 3652 Avenue Lava1 Montreal, Canada H2X 3C9 ISBN O-920393-37-3 Published simultaneously in the U.S.A. -

An Analysis of the World Baseball Classic As a Global Branding Promotional Strategy for Major League Baseball

Taking the Ballgame Out to the World: An Analysis of the World Baseball Classic as a Global Branding Promotional Strategy for Major League Baseball Benjamin D. Goss KEYWORDS: AbsTRACT baseball, Major League Baseball, World Baseball Classic, globalization, This paper analyzes the 2006 World Baseball Classic as a promotional strategy by Major League internationalization, Baseball to further its global branding pursuits. The WBC is qualified as a global sport event international sport that is a marketing function of MLB in its efforts to emerge as an international brand; elements of management, global brand, the WBC are examined in the context of a global brand strategy. WBC promotional execution global brand consumers, global media, global events, elements are studied in light of dimensions upon which consumers evaluate global brands. Four sport promotions, branding customer segments targeted through the WBC are characterized before the paper examines future strategy WBC marketing approaches in the context of cultural production. Goss, B. D. (2009). Taking the ballgame out to the world: An analysis of the world baseball classic as a global branding promotional strategy for Major League Baseball. Journal of Sport Administration & Supervision 1(1), 75-95. doi:10.3883/ v1i1_goss; published online April, 2009. Dr. Benjamin D. Goss is an WBC,” 2006; Fisher, 2006b). The tournament, assistant professor of management Overview of World Baseball Classic in the Department of Management which featured three rounds of competition, at Missouri State University in After years of planning, Major League Springfield, Missouri, USA. sold 737,112 tickets, was broadcast in He teaches sport, event, and Baseball (MLB) staged an international baseball nine languages, and was covered by 5,354 sponsorship management courses tournament known as the World Baseball in the Entertainment Management credentialed media members (Bloom, 2006; program. -

Abused Submissives in the BDSM Community Through a Gendered Framework

Kriminologiska institutionen Abused submissives in the BDSM community through a gendered framework A qualitative study Examensarbete 15 hp Kriminologi Kriminologi, kandidatkurs (30 hp) Höstterminen 2013 Tea Fredriksson Summary This study examines how abuse is viewed and talked about in the BDSM community. Particular attention is paid to gender actions and how a gendered framework of masculinities and femininities can further the understanding of how abuse is discussed within the community. The study aims to explore how sexual abuse of submissive men is viewed and discussed within the BDSM community, as compared to that of women. The study furthermore focuses on heterosexual contexts, with submissive men as victims of female perpetrators as its primary focus. To my knowledge, victimological research dealing with the BDSM community and its own views and definitions of abuse has not been conducted prior to the present study. Thus, the study is based on previous research into consent within BDSM, as this research provides a framework for non-consent as well. To conduct this study I have interviewed six BDSM practitioners. Their transcribed stories were then subjected to narrative analysis. The analysis of the material shows that victim blaming tendencies exist in the community, and that these vary depending on the victim’s gender. The findings indicate that the community is prone to victim blaming, and that this manifests itself differently for men and women. Furthermore, my results show that male rape myths can be used to understand cool victim-type explanations given by male victims of abuse perpetrated by women. After discussing my results, I suggest possible directions for further research. -

Syllabus Provides the Web Addresses

ETHN 189 , Wed 5-7:50, PCYNH 106 Jonathan Markovitz University of California, San Diego Office: Social Science Bldg 249 Winter, 2007 Office Hours: Tu 5:10-6:40; W 3:10-4:40 BLACK CINEMA Mainstream cinema has been one of the primary sites for the production and rearticulation of meanings of “blackness” since D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation (1915) and the dawn of the studio system. Griffith’s film consolidated and disseminated powerful racist myths to a national audience, helping to solidify white supremacy while providing ideological justification for lynching. While 1915 marks a low point in cinematic depictions of American race relations, much of the latter history of Hollywood film making is similarly problematic when it comes to representations of African Americans. There is, however, an alternative cinematic tradition that has only begun to receive the attention it is due. Just a few years after Birth, an African American film maker named Oscar Micheaux released Within Our Gates (1919), challenging the racism of Birth, and putting forward an alternative understanding of lynching and the brutality of white supremacy. In subsequent years and decades there has been a vibrant tradition of African American independent filmmaking. This course will examine that tradition, focusing on the work of filmmakers ranging from Micheaux to Gordon Parks to Spike Lee to Julie Dash. We will also venture briefly outside of the United States and address film making within the black diaspora. Throughout the course, we will focus on the social critiques posed by various black film makers, the relationships between mainstream and independent cinema, and the power of film as a social force. -

Directors Guild of America Creative Rights Handbook 2011 - 2014

DIRECTORS GUILD OF AMERICA CREATIVE RIGHTS HANDBOOK 2011 - 2014 Los Angeles, CA (310) 289-2000 New York, NY (212) 581-0370 Chicago, IL (312) 644-5050 www.dga.org Taylor Hackford, President • Jay D. Roth, National Executive Director Dear Colleague, As Co-Chairs of the DGA Creative Rights Committee, we spend a lot of time talking to Directors about their Theatrical Creative Rights work problems. Often we nd that trouble begins with Committee TABLE OF CONTENTS those who are unclear about or unaware of creative Jonathan Mostow Steven Soderbergh rights protections they already have as members of the Co-Chair Co-Chair Directors Guild of America. David Ayer Taylor Hackford Donald Petrie CREATIVE RIGHTS CHECKLISTS Some DGA Directors have voiced frustration over Michael Bay John Lee Hancock Sam Raimi Checklists of DGA Directors’ creative rights, practices in the editing room; they did not know John Carpenter Curtis Hanson Brett Ratner codied in this handbook that the DGA Basic Agreement protects them from .…..................….…….…….…….…….….3 interference when they are preparing their cut. Some omas Carter Mary Lambert Jay Roach television Directors have expressed concern about being Martha Coolidge Jonathan Lynn Tom Shadyac excluded from the looping and dubbing process; they Wes Craven Michael Mann Brad Silberling were unaware that they, like feature Directors, have SUMMARY OF CREATIVE RIGHTS Andy Davis Frank Marshall Penelope Spheeris the right to participate in both. And many Directors A summary of a Director’s creative rights did not realize that, because they are Guild members, Roger Donaldson McG Betty omas under the Directors Guild of America Basic they have a right to additional cutting time if necessary David Fincher E. -

Grand Vinyl Weekend! 24-25 October 2020 20 Happening

GRAND VINYL WEEKEND! 24-25 OCTOBER 2020 20 HAPPENING HITS VOL 2 BRANDY SCOTT ENGLISH MOST PEOPLE I KNOW THINK THAT I'M CRAZY BILLY THORPE & THE AZTECS OPEN UP YOUR HEART G WAYNE THOMAS THEME FROM SHAFT ISAAC HAYES LEVON ELTON JOHN COZ I LUV YOU SLADE SHOW ME THE WAY BRIAN CADD/DON MUDIE 1986 WAY TO GO TALK TO ME STEVIE NICKS CHAIN REACTION DIANA ROSS DEATH DEFYING HOO DOO GURUS DISCO DAZZLER EVERY 1'S A WINNER HOT CHOCOLATE BABY HOLD ON EDDIE MONEY IF YOU CAN'T GIVE ME LOVE SUZI QUATRO SUPERSOUND GLAD ALL OVER HUSH GONNA MAKE YOU A STAR DAVID ESSEX BORN TO RUN BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN WORLD OF MAKE BELIEVE STYLUS FROM THE INSIDE MARCIA HINES ONCE BITTEN TWICE SHY IAN HUNTER TOO MUCH FANDANGO RITZI 1980 THE MUSIC CRAZY LITTLE THING CALLED LOVE QUEEN TIRED OF TOWING THE LINE ROCKY BURNETTE SAME OLD GIRL DARYL COTTON HOW DO I MAKE YOU LINDA RONSTADT 24 HAPPENING HITS WOMAN YOU'RE BREAKING ME GROOP I THINK WE'RE ALONE NOW TOMMY JAMES & THE SHONDELLS WOMAN WOMAN GARY PUCKETT & UNION GAP 83 THRU THE ROOF BOP GIRL PAT WILSON TELL HER ABOUT IT BILLY JOEL MAXINE SHARON O'NEIL RAIN DRAGON NO SENSE COLD CHISEL SHAKE YOUR TAILFEATHER BLUES BROTHERS/RAY CHARLES KARMA CHAMELEON CULTURE CLUB 20 SOLID HITS ALL RIGHT NOW FREE BAND OF GOLD FREDA PAYNE MR BOJANGLES NITTY GRITTY DIRT BAND YOUR SONG ELTON JOHN CHIRPY CHIRPY CHEEP CHEEP MIDDLE OF THE ROAD SAN BERNADINO CHRISTIE RIPPER HORROR MOVIE SKYHOOKS I GET A KICK OUT OF YOU GARY SHEARSTON DOWN DOWN STATUS QUO NEVER CAN SAY GOODBYE GLORIA GAYNOR GIRLS ON THE AVENUE RICHARD CLAPTON IF YOU LOVE ME OLIVIA NEWTON-JOHN FREEDOM SHERBET PRIME CUTS ANTMUSIC ADAM AND THE ANTS INTO THE NIGHT BENNY MARDONES ROCK HARD SUZI QUATRO ACCORDING TO MY HEART THE REELS LITTLE JEANNIE ELTON JOHN FAME IRENE CARA I AM THE BEAT THE LOOK FANTASTIC DANCIN' (ON A SATURDAY NIGHT) BARRY BLUE COME ON FEEL THE NOIZE SLADE STANDING ON THE INSIDE NEIL SEDAKA I REMEMBER WHEN I WAS YOUNG MATT TAYLOR BAND PLAYED THE BOOGIE C.C.S. -

Brett Ratner

SLATE Brett Ratner Brett Ratner is one of Hollywood’s most successful filmmakers. His diverse films resonate with audiences worldwide and, as director, his films have grossed over $2 billion at the global box office. Brett began his career directing music videos before making his feature directorial debut at 26 years old with the action comedy hit Money Talks. He followed with the blockbuster Rush Hour and its successful sequels. Brett also directed The Family Man, Red Dragon, After the Sunset, X- Men: The Last Stand, Tower Heist and Hercules. Ratner has also enjoyed critical acclaim and box office success as a producer. He has served as an executive producer on the Golden Globe and Oscar winning The Revenant, starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Black Mass, starring Johnny Depp, and War Dogs, starring Jonah Hills ; and as a producer on Truth, starring Robert Redford and Cate Blanchett; I Saw the Light, starring Tom Hiddleston and Elizabeth Olsen; and Rules Don’t Apply, written, directed and produced by Warren Beatty. His other produced films include the smash hit comedy Horrible Bosses and its sequel, and the re-imagined Snow White tale Mirror Mirror. His additional producing credits include the documentaries Author: The JT LeRoy Story, Catfish, the Emmy-nominated Woody Allen - A Documentary, Helmut by June, I Knew It Was You: Rediscovering John Cazale, Chuck Norn's vs. Communism, the 5-time Emmy nominated and Peabody Award winning Night Will Fall, HBO’s Bright Lights, and National Geographic’s Before the Flood, with Fisher Stevens and Leonardo DiCaprio. He also executive produced and directed the Golden Globe-nominated FOX series Prison Break, and executive produced the television series Rush Hour, based on his hit films. -

The A-Z of Brent's Black Music History

THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY BASED ON KWAKU’S ‘BRENT BLACK MUSIC HISTORY PROJECT’ 2007 (BTWSC) CONTENTS 4 # is for... 6 A is for... 10 B is for... 14 C is for... 22 D is for... 29 E is for... 31 F is for... 34 G is for... 37 H is for... 39 I is for... 41 J is for... 45 K is for... 48 L is for... 53 M is for... 59 N is for... 61 O is for... 64 P is for... 68 R is for... 72 S is for... 78 T is for... 83 U is for... 85 V is for... 87 W is for... 89 Z is for... BRENT2020.CO.UK 2 THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY This A-Z is largely a republishing of Kwaku’s research for the ‘Brent Black Music History Project’ published by BTWSC in 2007. Kwaku’s work is a testament to Brent’s contribution to the evolution of British black music and the commercial infrastructure to support it. His research contained separate sections on labels, shops, artists, radio stations and sound systems. In this version we have amalgamated these into a single ‘encyclopedia’ and added entries that cover the period between 2007-2020. The process of gathering Brent’s musical heritage is an ongoing task - there are many incomplete entries and gaps. If you would like to add to, or alter, an entry please send an email to [email protected] 3 4 4 HERO An influential group made up of Dego and Mark Mac, who act as the creative force; Gus Lawrence and Ian Bardouille take care of business. -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

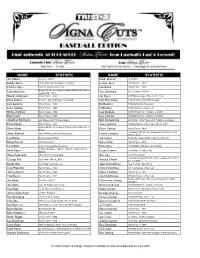

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank