1 Microhabitat Use of the Eastern Fence Lizard (Sceloporus Undulatus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nonnative Reptilies in South Florida ID Guide

Nonnative Reptiles in South Florida Identification Guide • The nonnative reptiles shown here are native to Central and South America, Asia, and Nonnative species are Africa. They were introduced to south Florida by human activity. sometimes confused with • Invasive species harm native species through direct predation, competition for resources, the Florida natives shown spread of disease, and disruption of natural ecosystems. Many of the nonnative reptiles on because their colorations this guide are, or have the potential to become, invasive. and patterns are very • Use this guide to identify invasive species and immediately report sightings of the black similar. Pay attention to the and white tegu, Nile monitor, and all invasive snakes to 1-888-IVE-GOT1. Take a distinct characteristics and photo and note the location relative to street intersections or with a GPS if possible. typical adult sizes listed on this guide to avoid • More photos can be found at www.flmnh.ufl.edu/herpetology/herpetology.htm. confusion when you • Be certain that an animal is a nonnative species before removing it. Warning-most encounter these animals. reptiles will bite or scratch if provoked. Nonnative Lizards NATIVE :- • ,,.., •· t ..... Look-a-Likes . ... ·-tt-..... • •. .. l . 1 '\..\ =- ' . ----.....·~·-· - - ',-<•'-' ' . \:,' . <! •.t'- . ,. '\. Dav id 13,irbsv ~ ·- ~ 9111'.', o:'"' w:' Black and White Tegu 2 to 3 ft. Dark bands with plentiful white dots between them Eastern Fence Lizard 3.5 to 7.5 in. Northern Curly-Tailed Lizard 7 to 10.5 in . Gray to tan with curled tail Florida Scrub Lizard 3.5 to 5.5 in. American Alligator 6 to 9 ft. Nile Monitor 4 to 6 ft. -

Hybridization Between Multiple Fence Lizard Lineages in an Ecotone

Molecular Ecology (2007) 16, 1035–1054 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03194.x HybridizationBlackwell Publishing Ltd between multiple fence lizard lineages in an ecotone: locally discordant variation in mitochondrial DNA, chromosomes, and morphology ADAM D. LEACHÉ* and CHARLES J. COLE†‡ *Museum of Vertebrate Zoology and Department of Integrative Biology, 3101 Valley Life Sciences Building, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-3160, USA, †Department of Herpetology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024-5192, USA Abstract We investigated a hybrid zone between two major lineages of fence lizards (Sceloporus cowlesi and Sceloporus tristichus) in the Sceloporus undulatus species complex in eastern Arizona. This zone occurs in an ecotone between Great Basin Grassland and Conifer Wood- land habitats. We analysed spatial variation in mtDNA (N = 401; 969 bp), chromosomes (N = 217), and morphology (N = 312; 11 characters) to characterize the hybrid zone and assess species limits. A fine-scale population level phylogenetic analysis refined the boundaries between these species and indicated that four nonsister mtDNA clades (three belonging to S. tristichus and one to S. cowlesi) are sympatric at the centre of the zone. Esti- mates of cytonuclear disequilibria in the population closest to the centre of the hybrid zone suggest that the S. tristichus clades are randomly mating, but that the S. cowlesi haplotype has a significant nonrandom association with nuclear alleles. Maximum-likelihood cline- fitting analyses suggest that the karyotype, morphology, and dorsal colour pattern clines are all coincident, but the mtDNA cline is skewed significantly to the south. A temporal comparison of cline centres utilizing karyotype data collected in the early 1970s and in 2002 suggests that the cline may have shifted by approximately 1.5 km to the north over a 30-year period. -

Significant New Records of Amphibians and Reptiles from Georgia, USA

GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION 597 Herpetological Review, 2015, 46(4), 597–601. © 2015 by Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Significant New Records of Amphibians and Reptiles from Georgia, USA Distributional maps found in Amphibians and Reptiles of records for a variety of amphibian and reptile species in Georgia. Georgia (Jensen et al. 2008), along with subsequent geographical All records below were verified by David Bechler (VSU), Nikole distribution notes published in Herpetological Review, serve Castleberry (GMNH), David Laurencio (AUM), Lance McBrayer as essential references for county-level occurrence data for (GSU), and David Steen (SRSU), and datum used was WGS84. herpetofauna in Georgia. Collectively, these resources aid Standard English names follow Crother (2012). biologists by helping to identify distributional gaps for which to target survey efforts. Herein we report newly documented county CAUDATA — SALAMANDERS DIRK J. STEVENSON AMBYSTOMA OPACUM (Marbled Salamander). CALHOUN CO.: CHRISTOPHER L. JENKINS 7.8 km W Leary (31.488749°N, 84.595917°W). 18 October 2014. D. KEVIN M. STOHLGREN Stevenson. GMNH 50875. LOWNDES CO.: Langdale Park, Valdosta The Orianne Society, 100 Phoenix Road, Athens, (30.878524°N, 83.317114°W). 3 April 1998. J. Evans. VSU C0015. Georgia 30605, USA First Georgia record for the Suwannee River drainage. MURRAY JOHN B. JENSEN* CO.: Conasauga Natural Area (34.845116°N, 84.848180°W). 12 Georgia Department of Natural Resources, 116 Rum November 2013. N. Klaus and C. Muise. GMNH 50548. Creek Drive, Forsyth, Georgia 31029, USA DAVID L. BECHLER Department of Biology, Valdosta State University, Valdosta, AMBYSTOMA TALPOIDEUM (Mole Salamander). BERRIEN CO.: Georgia 31602, USA St. -

Response of Reptile and Amphibian Communities to the Reintroduction of Fire T in an Oak/Hickory Forest ⁎ Steven J

Forest Ecology and Management 428 (2018) 1–13 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Forest Ecology and Management journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foreco Response of reptile and amphibian communities to the reintroduction of fire T in an oak/hickory forest ⁎ Steven J. Hromadaa, , Christopher A.F. Howeyb,c, Matthew B. Dickinsond, Roger W. Perrye, Willem M. Roosenburgc, C.M. Giengera a Department of Biology and Center of Excellence for Field Biology, Austin Peay State University, Clarksville, TN 37040, United States b Biology Department, University of Scranton, Scranton, PA 18510, United States c Ohio Center for Ecology and Evolutionary Studies, Department of Biological Sciences, Ohio University, Athens, OH 45701, United States d Northern Research Station, U.S. Forest Service, Delaware, OH 43015, United States e Southern Research Station, U.S. Forest Service, Hot Springs, AR 71902, United States ABSTRACT Fire can have diverse effects on ecosystems, including direct effects through injury and mortality and indirect effects through changes to available resources within the environment. Changes in vegetation structure suchasa decrease in canopy cover or an increase in herbaceous cover from prescribed fire can increase availability of preferred microhabitats for some species while simultaneously reducing preferred conditions for others. We examined the responses of herpetofaunal communities to prescribed fires in an oak/hickory forest in western Kentucky. Prescribed fires were applied twice to a 1000-ha area one and four years prior to sampling, causing changes in vegetation structure. Herpetofaunal communities were sampled using drift fences, and vegetation attributes were sampled via transects in four burned and four unburned plots. Differences in reptile community structure correlated with variation in vegetation structure largely created by fires. -

Ventral Coloration and Body Condition Do Not Affect Territorial Behavior in Two Sceloporus Lizards

Ventral coloration and body condition do not affect territorial behavior in two Sceloporus lizards 1Marina Kelada, 1Courtney Moulton, 2Casey Nguyen, 3Griselda Robles Olague 1University of California, Riverside; 2University of California, Irvine; 3University of California, Santa Barbara Sceloporus lizards are known to be defensive of their territories, which provide shelter, food, water, and mates. They often exhibit territorial behavior through visual displays of aggression, specifically with pushups. Along with aggression, this display can also expose the blue coloration on their ventral side, serving as an intraspecific communication between lizards that reveals information about their dominance, sex, and species membership. In this study, we compared how blue coloration and body condition affected territorial behavior in two Sceloporus lizards: the well-studied western fence (Sceloporus occidentalis) and the understudied sagebrush (Sceloporus graciosus), two closely related lizards with overlapping ranges in the San Jacinto Mountains. We also addressed whether these species would exhibit character displacement in their ventral coloration as a result of their sympatry. ImageJ and Adobe Photoshop were used for photo analyses to quantify the proportion and intensity of blue on each lizard’s ventral side. Territoriality was measured through number of pushups displayed and distance traveled. We found that both ventral coloration and body condition had no effect on the territoriality of either species, suggesting that territorial behavior -

Maryland Envirothon: Wildlife Section

3/17/2021 Maryland Envirothon: Class Amphibia & Reptilia KERRY WIXTED WILDLIFE AND HERITAGE SERVICE March 2021 1 Amphibia Overview •>40 species in Maryland •Anura (frogs & toads) •Caudata (salamanders & newts) •Lay soft, jelly-like eggs (no shell) •Have larval state with gills •Breathe & drink through skin Gray treefrog by Kerry Wixted Note: This guide is an overview of select species found in Maryland. 2 Anura • ~20 species in Maryland • Frogs & toads • Short-bodied & tailless (as adults) • Typically lay eggs in water & hatch into aquatic larvae Green treefrog by Kerry Wixted Order: Anura 3 1 3/17/2021 Family Bufonidae (Toads) Photo by Kerry Wixted by Photo Kerry Photo by Judy Gallagher CC 2.0 CC by by Photo Gallagher Judy American Toad (Anaxyrus americanus ) Fowler's Toad (Anaxyrus fowleri) 2-3.5”; typically 1-2 spots/ wart; parotoid gland is 2-3”; typically 3+ spots/ wart; parotoid gland separated from the cranial crest or connected narrowly is in contact w/ the cranial crest; Call: a short, by a spur; enlarged warts on tibia; Call: an elongated trill brash and whiny call lasting 2-4 seconds or whir lasting 5-30 seconds and resembles a simultaneous whistle and hum Order: Anura; Family Bufonidae 4 Family Hylidae (Treefrogs) Spring Peeper Gray Treefrog & Cope’s Gray Treefrog (Pseudacris crucifer) (Hyla versicolor & Hyla chrysoscelis) 0.75 - 1.25”; Brown, tan, or yellowish with dark X-shaped 1.25 - 2” (Identical in appearance); Gray to white with mark on back; Dark bar between eye; Mask from nose darker streaking, resembling a tree knot; Cream square through eye and tympanum, often extending down side below each eye; Inner thigh yellow or orange; enlarged Call: Clear, shrill, high-pitched whistle or peep toe pads; Call (H. -

Spatial Dynamics of Nesting Behavior: Lizards Shift Icrm Ohabitats to Construct Nests with Beneficial Thermal Properties Michael W

Clemson University TigerPrints Publications Biological Sciences 10-2009 Spatial Dynamics of Nesting Behavior: Lizards Shift icrM ohabitats to Construct Nests with Beneficial Thermal Properties Michael W. Sears Clemson University, [email protected] Michael J. Angilletta Robert M. Pringle Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/bio_pubs Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Please use publisher's recommended citation. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Notes Ecology, 90(10), 2009, pp. 2933–2939 Ó 2009 by the Ecological Society of America Spatial dynamics of nesting behavior: Lizards shift microhabitats to construct nests with beneficial thermal properties 1,3 1,4 2 MICHAEL J. ANGILLETTA,JR., MICHAEL W. SEARS, AND ROBERT M. PRINGLE 1Department of Biology, Indiana State University, Terre Haute, Indiana 47809 USA 2Department of Biological Sciences, Stanford University, Stanford, California 94305 USA Abstract. Because temperature affects the growth, development, and survival of embryos, oviparous mothers should discriminate carefully among available nesting sites. We combined a radiotelemetric study of animal movements with a spatial mapping of environmental temperatures to test predictions about the nesting behavior of the eastern fence lizard (Sceloporus undulatus). Females made large excursions from their typical home ranges to construct nests in exposed substrates. These excursions appeared to be related solely to nesting because all females returned to forested habitat immediately afterward. On average, ,1% (range ¼ 0–8%, n ¼ 19) of the area used by a female during nesting was contained within the area used before and after nesting. -

Natural History Series: Nine-Banded Armadillo

The University of Georgia College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences and the D.B. Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources Natural History Series Nine-Banded Armadillo (Dasy pus novem cinctus) Michael T. Me ngak, Associate Professor and Wil dlife Outreach Specialist D.B. Warnell School of Forest Resources Introduction rhinoceros lived in South America, and small cousins lived as far north as Canada. These disappeared in the Scientists classify armadillos with anteaters and ice ages long before humans inhabited North America. sloths. This tells us that they have poorly developed teeth and limited mobility. In fact, armadillos have Taxonomy small, peg-like teeth that are useful for grinding their food but of little value for capturing prey. No other Order Xenarthra – Armadillos, Anteaters, and Sloths mammal in Georgia has bony skin plates or a “shell,” Family Dasypodidae – Armadillo which makes the armadillo easy to identify. Just like a Nine-banded Armadillo – Dasypus novemcinctus turtle, the shell is called a carapace. Armadillos are common in central and southern Georgia and are moving northward. Only one species of armadillo lives in Georgia and the southeastern United States, but 20 recognized species are found throughout Central and South America. These include the giant armadillo, which can weigh up to 130 pounds, and the pink fairy armadillo, which weighs less than 4 ounces. About two million years ago a relative of the armadillo as large as a The genus name, Dasypus, is thought to be derived Georgia but, in fact, they are present as far north as from a Greek word for hare or rabbit. -

New York State Endangered Species List

January 24, 2020 Submitted via Electronic Mail Joe Racette NYSDEC Division of Fish and Wildlife 625 Broadway Albany, NY 12233-4754 [email protected] Re: Endangered Species List Dear Mr. Racette, We are writing on behalf of the Center for Biological Diversity, Riverkeeper, New York City Audubon, and Nadya Ali, to support the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation’s (DEC) proposal to provide new or increased protections for 46 species through its lists of endangered, threatened, and special concern species. This proposal is particularly timely as the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services recently warned governments around the world that 1 million species are now at risk of extinction because of human activity. Urgent actions are needed to avert mass extinction in the coming decades. Yet, under the current administration, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has extended protections to only 19 species under the federal Endangered Species Act, fewer than any other administration at the same point in the presidential term. Accordingly, we applaud DEC taking initiative and updating its list of state endangered and threatened species. While we generally support the additions to the endangered, threatened, and special concern lists, we also urge you provide stronger protections for the Atlantic Coast leopard frog, eastern hellbender, American eel, American shad, eastern fence lizard, and eastern tiger salamander. In support of our request, we submit the following scientific information demonstrating that these species meet the listing criteria necessary to warrant stronger protection. The Center for Biological Diversity is a national nonprofit organization dedicated to protecting imperiled species and wild places. -

Legal Authority Over the Use of Native Amphibians and Reptiles in the United States State of the Union

STATE OF THE UNION: Legal Authority Over the Use of Native Amphibians and Reptiles in the United States STATE OF THE UNION: Legal Authority Over the Use of Native Amphibians and Reptiles in the United States Coordinating Editors Priya Nanjappa1 and Paulette M. Conrad2 Editorial Assistants Randi Logsdon3, Cara Allen3, Brian Todd4, and Betsy Bolster3 1Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies Washington, DC 2Nevada Department of Wildlife Las Vegas, NV 3California Department of Fish and Game Sacramento, CA 4University of California-Davis Davis, CA ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS WE THANK THE FOLLOWING PARTNERS FOR FUNDING AND IN-KIND CONTRIBUTIONS RELATED TO THE DEVELOPMENT, EDITING, AND PRODUCTION OF THIS DOCUMENT: US Fish & Wildlife Service Competitive State Wildlife Grant Program funding for “Amphibian & Reptile Conservation Need” proposal, with its five primary partner states: l Missouri Department of Conservation l Nevada Department of Wildlife l California Department of Fish and Game l Georgia Department of Natural Resources l Michigan Department of Natural Resources Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies Missouri Conservation Heritage Foundation Arizona Game and Fish Department US Fish & Wildlife Service, International Affairs, International Wildlife Trade Program DJ Case & Associates Special thanks to Victor Young for his skill and assistance in graphic design for this document. 2009 Amphibian & Reptile Regulatory Summit Planning Team: Polly Conrad (Nevada Department of Wildlife), Gene Elms (Arizona Game and Fish Department), Mike Harris (Georgia Department of Natural Resources), Captain Linda Harrison (Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission), Priya Nanjappa (Association of Fish & Wildlife Agencies), Matt Wagner (Texas Parks and Wildlife Department), and Captain John West (since retired, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission) Nanjappa, P. -

Texas Master Naturalist Hill Country Chapter June 2004 Newsletter

Texas Master Naturalist Hill Country Chapter June 2004 Newsletter June 28th Meeting: A Potluck Picnic in the Park This month our meeting will be a Family Potluck Picnic in Louise Hayes Park on the Guadalupe River in Kerrville. We want our members and their families to come and get to know each other better, since we don't all volunteer for the same projects, or see each other that often since we hail from four different counties. We want this picnic to be a way to visit and enjoy each other. We have the Group Pavilion reserved from 5 PM to 9 PM, but feel free to come earlier to practice your plant and tree identification, chat with your friends, or simply enjoy the river. Bring frisbees or whatever sports equipment might be fun in the park. We plan to eat at 6 PM. Everyone is asked to bring a cold dish to share and a serving utensil. Bringing your own lawn chair will give you many more options on where you sit to enjoy the tranquility of the park, perhaps even on Tranquility Island in the middle of the river. The Chapter will provide soft drinks. If you plan to attend, please RSVP to Emily Matheson at [email protected] or 830-796-7680 so that we can have enough drinks etc.. While we welcome visitors to most of our meetings, this Picnic is for “Members Only”, and their families, and folks who have applied for our Training Classes, or who think that they might be interested in applying. -

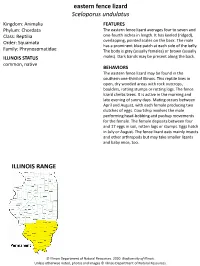

Eastern Fence Lizard Sceloporus Undulatus ILLINOIS RANGE

eastern fence lizard Sceloporus undulatus Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata The eastern fence lizard averages four to seven and Class: Reptilia one-fourth inches in length. It has keeled (ridged), Order: Squamata overlapping, pointed scales on the back. The male has a prominent blue patch at each side of the belly. Family: Phrynosomatidae The body is gray (usually females) or brown (usually ILLINOIS STATUS males). Dark bands may be present along the back. common, native BEHAVIORS The eastern fence lizard may be found in the southern one-third of Illinois. This reptile lives in open, dry wooded areas with rock outcrops, boulders, rotting stumps or rotting logs. The fence lizard climbs trees. It is active in the morning and late evening of sunny days. Mating occurs between April and August, with each female producing two clutches of eggs. Courtship involves the male performing head-bobbing and pushup movements for the female. The female deposits between four and 17 eggs in soil, rotten logs or stumps. Eggs hatch in July or August. The fence lizard eats mainly insects and other arthropods but may take smaller lizards and baby mice, too. ILLINOIS RANGE © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2020. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. © Mary Kay Rubey © Mary Kay Rubey © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2020. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. Aquatic Habitats rivers and streams Woodland Habitats coniferous forests; upland deciduous forests Prairie and Edge Habitats none © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2020.