Appreciating Reptiles and Amphibians in Nature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nonnative Reptilies in South Florida ID Guide

Nonnative Reptiles in South Florida Identification Guide • The nonnative reptiles shown here are native to Central and South America, Asia, and Nonnative species are Africa. They were introduced to south Florida by human activity. sometimes confused with • Invasive species harm native species through direct predation, competition for resources, the Florida natives shown spread of disease, and disruption of natural ecosystems. Many of the nonnative reptiles on because their colorations this guide are, or have the potential to become, invasive. and patterns are very • Use this guide to identify invasive species and immediately report sightings of the black similar. Pay attention to the and white tegu, Nile monitor, and all invasive snakes to 1-888-IVE-GOT1. Take a distinct characteristics and photo and note the location relative to street intersections or with a GPS if possible. typical adult sizes listed on this guide to avoid • More photos can be found at www.flmnh.ufl.edu/herpetology/herpetology.htm. confusion when you • Be certain that an animal is a nonnative species before removing it. Warning-most encounter these animals. reptiles will bite or scratch if provoked. Nonnative Lizards NATIVE :- • ,,.., •· t ..... Look-a-Likes . ... ·-tt-..... • •. .. l . 1 '\..\ =- ' . ----.....·~·-· - - ',-<•'-' ' . \:,' . <! •.t'- . ,. '\. Dav id 13,irbsv ~ ·- ~ 9111'.', o:'"' w:' Black and White Tegu 2 to 3 ft. Dark bands with plentiful white dots between them Eastern Fence Lizard 3.5 to 7.5 in. Northern Curly-Tailed Lizard 7 to 10.5 in . Gray to tan with curled tail Florida Scrub Lizard 3.5 to 5.5 in. American Alligator 6 to 9 ft. Nile Monitor 4 to 6 ft. -

Contributions of Intensively Managed Forests to the Sustainability of Wildlife Communities in the South

CONTRIBUTIONS OF INTENSIVELY MANAGED FORESTS TO THE SUSTAINABILITY OF WILDLIFE COMMUNITIES IN THE SOUTH T. Bently Wigley1, William M. Baughman, Michael E. Dorcas, John A. Gerwin, J. Whitfield Gibbons, David C. Guynn, Jr., Richard A. Lancia, Yale A. Leiden, Michael S. Mitchell, Kevin R. Russell ABSTRACT Wildlife communities in the South are increasingly influenced by land use changes associated with human population growth and changes in forest management strategies on both public and private lands. Management of industry-owned landscapes typically results in a diverse mixture of habitat types and spatial arrangements that simultaneously offers opportunities to maintain forest cover, address concerns about fragmentation, and provide habitats for a variety of wildlife species. We report here on several recent studies of breeding bird and herpetofaunal communities in industry-managed landscapes in South Carolina. Study landscapes included the 8,100-ha GilesBay/Woodbury Tract, owned and managed by International Paper Company, and 62,363-ha of the Ashley and Edisto Districts, owned and managed by Westvaco Corporation. Breeding birds were sampled in both landscapes from 1995-1999 using point counts, mist netting, nest searching, and territory mapping. A broad survey of herpetofauna was conducted during 1996-1998 across the Giles Bay/Woodbury Tract using a variety of methods, including: searches of natural cover objects, time-constrained searches, drift fences with pitfall traps, coverboards, automated recording systems, minnow traps, and turtle traps. Herpetofaunal communities were sampled more intensively in both landscapes during 1997-1999 in isolated wetland and selected structural classes. The study landscapes supported approximately 70 bird and 72 herpetofaunal species, some of which are of conservation concern. -

Blue–Spotted Salamander Ambystoma Laterale Status: Wisconsin – Common Minnesota – Common Iowa – Endangered

Species Descriptions Blue–spotted Salamander Ambystoma laterale Status: Wisconsin – Common Minnesota – Common Iowa – Endangered 1 cm Size at hatching, 8 – 10 mm total length; at metamorphosis, ~ 34 mm snout–vent length The Blue-spotted Salamander is one of four mole salamanders in our region. Other mole salamanders include the Spotted, Small-mouthed, and Tiger Salamanders. As adults, mole salamanders live under cover objects such as rotting logs or in burrows in the forest floor (Parmelee 1993). In early spring (March and April), adults migrate to temporary ponds to breed. Larvae develop during spring and summer and usually metamorphose in the fall. The Blue-spotted Salamander is a woodland species of northern North America. The eggs are laid in small clumps (7–40 eggs) attached to vegetation or debris at the bottom of ponds. The larvae are similar to Spotted Salamanders but are more darkly colored with the fins mottled with black, and dark blotches on the dorsum. Blue-spotted Salamanders metamorphose at about the same size as Spotted Salamanders but are darker, sometimes with flecks of blue. 14 15 Spotted Salamander Ambystoma maculatum Status: Wisconsin – Locally abundant Minnesota – Status to be determined 1 cm Size at hatching, 12 – 17 mm; at metamorphosis, 49 – 60 mm total length The Spotted Salamander is present only in the northeastern part of our range (where it is sympatric with up to two other mole salamanders). Females deposit eggs in a firm oval mass (60–100 mm in diameter) attached to vegetation near the surface of the water. The eggs (1–250 per mass) are black, but the egg mass may be clear or milky, with a greenish hue because of symbiotic algae. -

Spotted Salamander (Ambystoma Maculafum)

Spotted Salamander (Ambystoma maculafum) RANGE: Nova Scotia and the Gaspe Peninsula to s. On- BREEDINGPERIOD: March to mid-April. Mass breeding tario, s. through Wisconsin, s. Illinois excluding prairie migrations occur in this species: individuals enter and regions, toe. Kansas andTexas, and through the Eastern leave breeding ponds using the same track each year, United States, except Florida, the Delmarva Peninsula, and exhibit fidelity to breeding ponds (Shoop 1956, and s. New Jersey. 1974). Individuals may not breed in consecutive years (Husting 1965). Breeding migrations occur during RELATIVE ABUNDANCEIN NEW ENGLAND:Common steady evening rainstorms. though populations declining, probably due to acid pre- cipitation. EGG DEPOSITION:1 to 6 days after first appearance of adults at ponds (Bishop 1941 : 114). HABITAT:Fossorial; found in moist woods, steambanks, beneath stones, logs, boards. Prefers deciduous or NO. EGGS/MASS:100 to 200 eggs, average of 125, laid in mixed woods on rocky hillsides and shallow woodland large masses of jelly, sometimes milky, attached to stems ponds or marshy pools that hold water through the sum- about 15 cm (6 inches) under water. Each female lays 1 to mer for breeding. Usually does not inhabit ponds con- 10 masses (average of 2 to 3) of eggs (Wright and Allen taining fish (Anderson 1967a). Terrestrial hibernator. In 1909).Woodward (1982)reported that females breeding summer often wanders far from water source. Found in in permanent ponds produced smaller, more numerous low oak-hickory forests with creeks and nearby swamps eggs than females using temporary ponds. in Illinois (Cagle 1942, cited in Smith 1961 :30). -

Heterotrophic Carbon Fixation in a Salamander-Alga Symbiosis

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.02.14.948299; this version posted February 18, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Heterotrophic Carbon Fixation in a Salamander-Alga Symbiosis. John A. Burns1,2, Ryan Kerney3, Solange Duhamel1,4 1Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University, Division of Biology and Paleo Environment, Palisades, NY 2Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, East Boothbay, ME 3Gettysburg College, Biology, Gettysburg, PA 4University of Arizona, Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology, Tucson, AZ Abstract The unique symbiosis between a vertebrate salamander, Ambystoma maculatum, and unicellular green alga, Oophila amblystomatis, involves multiple modes of interaction. These include an ectosymbiotic interaction where the alga colonizes the egg capsule, and an intracellular interaction where the alga enters tissues and cells of the salamander. One common interaction in mutualist photosymbioses is the transfer of photosynthate from the algal symbiont to the host animal. In the A. maculatum-O. amblystomatis interaction, there is conflicting evidence regarding whether the algae in the egg capsule transfer chemical energy captured during photosynthesis to the developing salamander embryo. In experiments where we took care to separate the carbon fixation contributions of the salamander embryo and algal symbionts, we show that inorganic carbon fixed by A. maculatum embryos reaches 2% of the inorganic carbon fixed by O. amblystomatis algae within an egg capsule after 2 hours in the light. -

The Origins of Chordate Larvae Donald I Williamson* Marine Biology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 7ZB, United Kingdom

lopmen ve ta e l B Williamson, Cell Dev Biol 2012, 1:1 D io & l l o l g DOI: 10.4172/2168-9296.1000101 e y C Cell & Developmental Biology ISSN: 2168-9296 Research Article Open Access The Origins of Chordate Larvae Donald I Williamson* Marine Biology, University of Liverpool, Liverpool L69 7ZB, United Kingdom Abstract The larval transfer hypothesis states that larvae originated as adults in other taxa and their genomes were transferred by hybridization. It contests the view that larvae and corresponding adults evolved from common ancestors. The present paper reviews the life histories of chordates, and it interprets them in terms of the larval transfer hypothesis. It is the first paper to apply the hypothesis to craniates. I claim that the larvae of tunicates were acquired from adult larvaceans, the larvae of lampreys from adult cephalochordates, the larvae of lungfishes from adult craniate tadpoles, and the larvae of ray-finned fishes from other ray-finned fishes in different families. The occurrence of larvae in some fishes and their absence in others is correlated with reproductive behavior. Adult amphibians evolved from adult fishes, but larval amphibians did not evolve from either adult or larval fishes. I submit that [1] early amphibians had no larvae and that several families of urodeles and one subfamily of anurans have retained direct development, [2] the tadpole larvae of anurans and urodeles were acquired separately from different Mesozoic adult tadpoles, and [3] the post-tadpole larvae of salamanders were acquired from adults of other urodeles. Reptiles, birds and mammals probably evolved from amphibians that never acquired larvae. -

Hybridization Between Multiple Fence Lizard Lineages in an Ecotone

Molecular Ecology (2007) 16, 1035–1054 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03194.x HybridizationBlackwell Publishing Ltd between multiple fence lizard lineages in an ecotone: locally discordant variation in mitochondrial DNA, chromosomes, and morphology ADAM D. LEACHÉ* and CHARLES J. COLE†‡ *Museum of Vertebrate Zoology and Department of Integrative Biology, 3101 Valley Life Sciences Building, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-3160, USA, †Department of Herpetology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, NY 10024-5192, USA Abstract We investigated a hybrid zone between two major lineages of fence lizards (Sceloporus cowlesi and Sceloporus tristichus) in the Sceloporus undulatus species complex in eastern Arizona. This zone occurs in an ecotone between Great Basin Grassland and Conifer Wood- land habitats. We analysed spatial variation in mtDNA (N = 401; 969 bp), chromosomes (N = 217), and morphology (N = 312; 11 characters) to characterize the hybrid zone and assess species limits. A fine-scale population level phylogenetic analysis refined the boundaries between these species and indicated that four nonsister mtDNA clades (three belonging to S. tristichus and one to S. cowlesi) are sympatric at the centre of the zone. Esti- mates of cytonuclear disequilibria in the population closest to the centre of the hybrid zone suggest that the S. tristichus clades are randomly mating, but that the S. cowlesi haplotype has a significant nonrandom association with nuclear alleles. Maximum-likelihood cline- fitting analyses suggest that the karyotype, morphology, and dorsal colour pattern clines are all coincident, but the mtDNA cline is skewed significantly to the south. A temporal comparison of cline centres utilizing karyotype data collected in the early 1970s and in 2002 suggests that the cline may have shifted by approximately 1.5 km to the north over a 30-year period. -

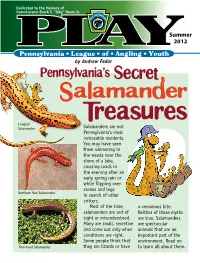

PA Salamanders

Summer 2012 by Andrew Fedor Longtail Salamander Salamanders are not Pennsylvania’s most noticeable residents. You may have seen them swimming in the weeds near the shore of a lake, crossing roads in the evening after an early spring rain or while flipping over stones and logs Northern Red Salamander in search of other critters. Most of the time, a venomous bite. salamanders are out of Neither of these myths sight or misunderstood. are true. Salamanders Many are small, secretive are spectacular and come out only when animals that are an conditions are right. important part of the Some people think that environment. Read on Four-toed Salamander they are lizards or have to learn all about them. www.fishandboat.com Pennsylvania Angler & Boater • July/August 2012 45 Many salamanders have a life Salamanders and other cycle similar to frogs and toads. amphibians like to breed They begin by emerging from in vernal pools, because eggs as larvae and later change predatory fish do not into adults. This transformation is live there. Many species called metamorphosis. brood or stay with their Adult female salamanders eggs to protect them Marbled Salamander lay eggs in the spring, summer from predators until or fall. The eggs are laid they hatch. individually, in small or large Eggs that are laid in masses or in long strands. Eggs ponds or streams hatch are laid in a moist environment, into larvae that must often a pond or vernal pool but live in the water. The sometimes under rocks or logs. A larvae look like miniature vernal pool is a seasonal pool of adults but with feathery Northern Dusky Salamander water that typically forms in the gills extending near their spring. -

Species of Greatest Conservation Need Species Accounts

2 0 1 5 – 2 0 2 5 Species of Greatest Conservation Need Species Accounts Appendix 1.4C-Amphibians Amphibian Species of Greatest Conservation Need Maps: Physiographic Provinces and HUC Watersheds Species Accounts (Click species name below or bookmark to navigate to species account) AMPHIBIANS Eastern Hellbender Northern Ravine Salamander Mountain Chorus Frog Mudpuppy Eastern Mud Salamander Upland Chorus Frog Jefferson Salamander Eastern Spadefoot New Jersey Chorus Frog Blue-spotted Salamander Fowler’s Toad Western Chorus Frog Marbled Salamander Northern Cricket Frog Northern Leopard Frog Green Salamander Cope’s Gray Treefrog Southern Leopard Frog The following Physiographic Province and HUC Watershed maps are presented here for reference with conservation actions identified in the species accounts. Species account authors identified appropriate Physiographic Provinces or HUC Watershed (Level 4, 6, 8, 10, or statewide) for specific conservation actions to address identified threats. HUC watersheds used in this document were developed from the Watershed Boundary Dataset, a joint project of the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture-Natural Resources Conservation Service, the U.S. Geological Survey, and the Environmental Protection Agency. Physiographic Provinces Central Lowlands Appalachian Plateaus New England Ridge and Valley Piedmont Atlantic Coastal Plain Appalachian Plateaus Central Lowlands Piedmont Atlantic Coastal Plain New England Ridge and Valley 675| Appendix 1.4 Amphibians Lake Erie Pennsylvania HUC4 and HUC6 Watersheds Eastern Lake Erie -

AMPHIBIANS of OHIO F I E L D G U I D E DIVISION of WILDLIFE INTRODUCTION

AMPHIBIANS OF OHIO f i e l d g u i d e DIVISION OF WILDLIFE INTRODUCTION Amphibians are typically shy, secre- Unlike reptiles, their skin is not scaly. Amphibian eggs must remain moist if tive animals. While a few amphibians Nor do they have claws on their toes. they are to hatch. The eggs do not have are relatively large, most are small, deli- Most amphibians prefer to come out at shells but rather are covered with a jelly- cately attractive, and brightly colored. night. like substance. Amphibians lay eggs sin- That some of these more vulnerable spe- gly, in masses, or in strings in the water The young undergo what is known cies survive at all is cause for wonder. or in some other moist place. as metamorphosis. They pass through Nearly 200 million years ago, amphib- a larval, usually aquatic, stage before As with all Ohio wildlife, the only ians were the first creatures to emerge drastically changing form and becoming real threat to their continued existence from the seas to begin life on land. The adults. is habitat degradation and destruction. term amphibian comes from the Greek Only by conserving suitable habitat to- Ohio is fortunate in having many spe- amphi, which means dual, and bios, day will we enable future generations to cies of amphibians. Although generally meaning life. While it is true that many study and enjoy Ohio’s amphibians. inconspicuous most of the year, during amphibians live a double life — spend- the breeding season, especially follow- ing part of their lives in water and the ing a warm, early spring rain, amphib- rest on land — some never go into the ians appear in great numbers seemingly water and others never leave it. -

Lizard ID Guide

Lizards of Anderson County, TN Lizards are extraordinary gifts of nature. World-wide there are close to 6,000 species. The United States is home to more than100 native species, along with many exotic species that have become established, especially in Florida. Tennessee has 9 species, 6 of which are listed for Anderson County. Some are fairly widespread and easy to observe, such as the Common Five-lined Skink below. Unfortunately, the liberal use of pesticides, combined with predation by free roaming house cats have taken a heavy toll on our lizard populations. Most lizards are insect eating machines and their ecological services should be promoted through backyard and schoolyard wildlife habitat projects. Lizard watching is great fun, and over time, observers can gain interesting insights into lizard behavior. Your backyard may be a good place to start your lizarding career. This guide will be helpful for identifying our local lizards and will also provide you with examples of lizard behaviors to observe. Some species must be captured—this can be challenging—to insure accurate identification. Please see the back page for more resources. Lizarding Lizard watching, often referred to as lizarding, will likely never be as popular as bird watching (birding), but there is an advantage to being a “lizarder.” Unlike birders, you don’t need to be an early riser. Bright sunny days with warm temperatures are the keys for successful lizarding, but like birding, close-up binoculars are helpful. A lizard’s life centers around three performance activities: 1) avoiding predators, 2) feeding, and 3) reproduction. Lizard performance is all about optimal body temperature. -

Significant New Records of Amphibians and Reptiles from Georgia, USA

GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION 597 Herpetological Review, 2015, 46(4), 597–601. © 2015 by Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Significant New Records of Amphibians and Reptiles from Georgia, USA Distributional maps found in Amphibians and Reptiles of records for a variety of amphibian and reptile species in Georgia. Georgia (Jensen et al. 2008), along with subsequent geographical All records below were verified by David Bechler (VSU), Nikole distribution notes published in Herpetological Review, serve Castleberry (GMNH), David Laurencio (AUM), Lance McBrayer as essential references for county-level occurrence data for (GSU), and David Steen (SRSU), and datum used was WGS84. herpetofauna in Georgia. Collectively, these resources aid Standard English names follow Crother (2012). biologists by helping to identify distributional gaps for which to target survey efforts. Herein we report newly documented county CAUDATA — SALAMANDERS DIRK J. STEVENSON AMBYSTOMA OPACUM (Marbled Salamander). CALHOUN CO.: CHRISTOPHER L. JENKINS 7.8 km W Leary (31.488749°N, 84.595917°W). 18 October 2014. D. KEVIN M. STOHLGREN Stevenson. GMNH 50875. LOWNDES CO.: Langdale Park, Valdosta The Orianne Society, 100 Phoenix Road, Athens, (30.878524°N, 83.317114°W). 3 April 1998. J. Evans. VSU C0015. Georgia 30605, USA First Georgia record for the Suwannee River drainage. MURRAY JOHN B. JENSEN* CO.: Conasauga Natural Area (34.845116°N, 84.848180°W). 12 Georgia Department of Natural Resources, 116 Rum November 2013. N. Klaus and C. Muise. GMNH 50548. Creek Drive, Forsyth, Georgia 31029, USA DAVID L. BECHLER Department of Biology, Valdosta State University, Valdosta, AMBYSTOMA TALPOIDEUM (Mole Salamander). BERRIEN CO.: Georgia 31602, USA St.