Pat Riley's Final Test

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Futureof Basketball the Futureof

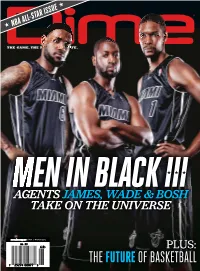

π NBA ALL-STAR ISSUE π MEN IN BLACK III AGENTS JAMES, WADE & BOSH TAKE ON THE UNIVERSE www.dimemag.comMAYA / #68 / MARCHMOORE 2012 TELLS US ALL HER PLUS: SECRETS THE FUTURE OF BASKETBALL Issue #68 March 2012 www.dimemag.com Editor & Publisher Josh Gotthelf – [email protected] Director of Content Patrick Cassidy – [email protected] Managing Editor Aron Phillips – [email protected] Staff Writer Sean Sweeney – [email protected] Art Direction Alexis Cook Contributing Photographers Keith Allison David Alvarez Sid Ashford Chris Charles Tom Ciszek Joe Epstein Bob Frischmann Steven Gabriele Rebecca Goldschmidt Dorothy Hong Brian Jenkins Gary Land Troy Paraiso Paul Savramis Brandon Smith 62 Miami Contributing Writers Michael Aufses Austin L. Burton Heat Julian Caldwell Alejandro Danois Andrew Greif Bryan Horowitz Jack Jensen Martin Kessler Daniel Marks Dylan Murphy Eric Newman Lucas Shapiro Dime Interns Ryan Imparato, Kevin Smith Dime NY Office 212.629.5066 Worldwide Newsstand Distributor Curtis Circulation Company, LLC. Newsstand Consultant Howard White & Associates DIME®, THE GAME. THE PLAYER. THE LIFE.® and THE BASKETBALL LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE® are registered trademarks of Dime Magazine Publishing Company, Inc. For new subscriptions, subscription problems and/or address changes please go to www.dimemag.com, call 818.286.3153 or e-mail [email protected] PRINTED IN THE USA 8 Photo. David Alvarez Does anyone else find it strange that the hottest months for our favorites to win the NBA championship in 2012. From there, basketball take place during the coldest months in America? All- we feature three of the NBA’s rising stars – Landry Fields, DeMar Star Weekend. -

Miami Heat: Is the Big Three Heading for Syndication?

Miami Heat: Is The Big Three Heading for Syndication? Author : Robert D. Cobb There was a time when Michael Jackson had to leave the Jackson 5 and go solo. Outkast broke up, Nysnc separated, Jay-Z and Dame Dash split, even the Beatles broke up. If you name your favorite sitcom over the last 30 years the most likely scenario for its ending was because people outgrew each other and there wasn't enough money to spread around. That's exactly what has to happen in Miami to keep LeBron James happy and winning. Miami had a great run atop the Eastern Conference, becoming only the third franchise to make it to four straight NBA Finals, winning back-to-back titles and recording the second longest winning streak in league history. In 2013, the Heat became the first team to win the title despite being last in the league in rebounding. Yet even with Pat Riley's public address it's impossible to whole-heartedly believe that adding minimum pieces to the quote unquote Big Three is enough to win any more championships. You're only as strong as your weakest link, which in this case is an undersized shooting guard, losing all athletic ability, who can't shoot, has fallen off as an elite defender and whose durability has only worsened over the course of his 11 seasons. Dwyane Wade has no value on the market because he has played awful on top of Father Time and intensifying gravity every time he tries to make a lay-up. Wade has never played in a full 82-game season and missed double-digit games during the lockout season. -

Spurs Still the Model Pro Franchise

CONTACT: Adam Thompson [email protected] SPORTS 920-453-5156 B1 Tuesday, June 17, 2014 www.sheboyganpress.com LOCAL BASEBALL NBA FINALS Post 83 Spurs still the model pro franchise sweeps By Brian Mahoney Painfully denied 12 10 rebounds for the Spurs, Associated Press months ago by the Heat, who added this title to the this victory party was ones they won in 1999, SAN ANTONIO — Tim worth the wait. 2003, ‘05 and ‘07 by shoot- foes Duncan and Tony Parker “We got to this spot and ing a finals-record 52.8 won titles in their second we didn’t let it go,” Ginobi- percent in the series. Sheboygan Press Media seasons. Manu Ginobili li said. “They played exquisite was a champion as an NBA San Antonio erased an basketball this series and Sheboygan’s Post 83 rookie. early 16-point deficit and in particular these last Legion baseball team al- Success came so quick- routed Miami for the three games and they are lowed just two runs in a ly and frequently for the fourth time in the series, the better team. There’s doubleheader sweep of Big Three, but San Anto- denying the Heat’s quest no other way to say it,” opponents on Sunday. nio couldn’t keep it up af- for a third straight cham- Heat coach Erik Spoelstra Sheboygan edged ter winning its last title in pionship. A year after the said. Marshfield 3-1 before run- 2007. And just when the Spurs suffered their only A decade and a half af- ruling Kenosha 11-1 in five Spurs were on the verge of loss in six finals appear- ter winning their first ti- innings. -

Montreal-Native Joel Anthony a Key Player on Miami Heat

NBA: Montreal-native Joel Anthony a key player on Miami Heat 6-foot-9, 260-pounder was once cut from the basketball team at Dawson College By BEN RABY, SPECIAL TO THE GAZETTE May 20, 2012 Joel Anthony #50 of the Miami Heat rebounds against Tyson Chandler #6 of the New York Knicks in Game Two of the Eastern Conference Quarterfinals during the 2012 NBA Playoffs on April 30, 2012 at American Airlines Arena in Miami, Florida. Photograph by: Nathaniel S. Butler , NBAE via Getty Images WASHINGTON – To say that the odds were stacked against Joel Anthony ever becoming an integral piece of a National Basketball Association title contender would be putting it mildly. Anthony was an undrafted Summer League invitee in July 2007 when the Miami Heat took a flyer on the 24-year-old Montreal native. He was the No. 3 centre on the team’s Summer League depth chart – about the equivalent of being a third-string goalie at a National Hockey League rookie camp. “He’s one of our favourite stories,” Miami head coach Erik Spoelstra said at a late-season Heat shootaround on the campus of Georgetown University. Spoelstra was an assistant coach under Pat Riley in 2007, but served as head coach during the July Summer League in Orlando, Fla. “There was one Summer League game where we were really looking at someone else, three players got hurt and so we had to play him,” Spoelstra recalled. “He wound up with seven blocks that game and four goaltending (calls), so we just said: ‘Let’s keep this guy on the radar.’” Three months later, Anthony was invited to Miami’s main training camp, where his primary purpose was to serve as “an added number,” according to Spoelstra. -

Lebron James to Return to Cleveland - WSJ

7/12/2014 LeBron James to Return to Cleveland - WSJ Dow Jones Reprints: This copy is for your personal, noncommercial use only. To order presentationready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, use the Order Reprints tool at the bottom of any article or visit www.djreprints.com See a sample reprint in PDF Order a reprint of this article now format. NBA LeBron James to Return to Cleveland Superstar Announces He Will Rejoin Cavaliers Four Years After Bolting By BEN COHEN Updated July 11, 2014 7:18 p.m. ET LeBron James throws up powder moments before game four of the NBA Eastern Conference Finals in 2009. Associated Press LeBron James, the singular talent in his generation of newly powerful professional basketball players, has decided to return to the hometown team he once spurned, a move that will rearrange the NBA's competitive furniture for years to come. James ended weeks of speculation about his basketball future Friday by announcing he will sign with the Cleveland Cavaliers, the team he played for in the first seven years of his career. James left in 2010 for Miami, where he won two NBA titles with the Heat. That decision four years ago, which was broadcast in a television special called "The Decision," resulted in a backlash against James in a city that had once revered him. He was cast as a villain as soon as he said he would "take my talents to South Beach" to join fellow superstars Dwyane Wade and Chris Bosh. http://online.wsj.com/articles/lebron-james-to-return-to-cleveland-1405096366#printMode 1/4 7/12/2014 LeBron James to Return to Cleveland - WSJ Friday's decision was more understated and felt far less engineered. -

Subject: NBA Finals 2011 in Dallas - Dallas Mavericks and Hotel Performance from Expedia/Hotels.Com - 6.14.11

Subject: NBA Finals 2011 in Dallas - Dallas Mavericks and Hotel Performance from Expedia/Hotels.com - 6.14.11 The city of Dallas is energized after winning a “…long-awaited first NBA title on Sunday, taking revenge on the Miami Heat by beating them 105-95 on their home court in Game 6 of the NBA finals” (WSJ). Support for our city’s team extends well beyond Texas, as a recent poll showed that the Dallas Mavericks were favored in the championship in every state except AL, FL, SC, WI (ESPN)! The Miami-Dallas series was repeatedly noted by sports commentators as one of the most exciting in recent memory, in game play and outcome: (Dallas Morning News) Rant Sports, a sports blog, confirmed the significance of this most recent sports final in Dallas – Ft. Worth, saying, “the city will be the first to host the Super Bowl, MLB World Series and NBA Finals in the same sports year….This is truly a unique experience for the Dallas-Fort Worth area. Just to add some extra icing on the cake, FC Dallas played in the MLS Cup in November, although the match took place in Ontario, Canada” (Rant Sports). NBA Finals 2011 – A Benefit to Dallas Hotels Like the Mavericks, Dallas hotels exhibited strong performance—year-over-year room night growth exceeded 20% and year-over-year ADR growth was greater than 2%—on each of the game dates: Dallas to Celebrate Mavericks Championship Win with Downtown Dallas Parade A parade will be hosted on Thursday, June 16th at 10am to celebrate the first- ever Mavericks National Championship. -

A Pareto Principle Analysis of the NBA: How Production Distribution Affects Team Success

51 A Pareto Principle Analysis of the NBA: How Production Distribution Affects Team Success Cole Berner, University of Alaska Fairbanks Joshua M. Lupinek, Montclair State University Jim Arkell, University of Alaska Fairbanks Margaret Keiper, University of Alaska Fairbanks Abstract The Pareto Principle, also known as the 80/20 rule, states that in general “80 percent of consequences stem from 20 percent of causes” (Bunkley, 2008, p. 1). This research examines the relationship between the 80/20 rule and the National Basketball Association (NBA) with respect to the distribution of individual player production through secondary data analysis and linear regression modeling. While there are only so many superstars to go around, this research examines the Pareto Principle as an analytic dashboard metric that league executives can look at to try to find success in the “Big Three Era.” Regression modeling from ten NBA seasons (2008/09 – 2017/18) shows a negative correlation between the 80/20 Principle and regular season wins, suggesting that NBA franchises be cautious of constructing top-heavy rosters. The equation and term “Simple Game Score” (SGS) is also introduced as a unique statistic. Introduction The purpose of this paper is to introduce a unique resource metric that both National Basketball Association (NBA) general managers and coaches can utilize longitudinally for roster construction within team analytic dashboard software (Athithya, 2019) where performance stats are represented in an interactive format. Additionally, the equation and term “Simple Game Score” (SGS) is also introduced as a unique statistic. This study continues the Global Sport Business Journal Pareto Principle discussion, brought forward in the article “A Pareto principle analysis of the NHL: Why ice hockey is the ultimate team game” (Lupinek, Chafin, & Arkell, 2017), by utilizing an 80/20 Principle theoretical framework to analyze whether NBA team success is influenced by the amount of production the top 20% of rostered players produce relative to the rest of the team. -

Was Awarded to This Guy As a Result of His Pleasant Interactions with the Local Media In

The “Good Guy Award” was awarded to this guy as a result of his pleasant interactions with the local media in Detroit. After attempting to save a pizza from falling off a seat, this guy lost control of his vehicle and crashed. In response, Digiorno gave this guy a free year’s supply of pizza. This guy is not Steve Hutchinson, but he was offered a seven year, forty-nine million dollar contract with the “poison pill” that the contract would be fully guaranteed if he played five games in one season in Minnesota. For ten points, remember this guy, a wide receiver who returned punts and played for the Minnesota Vikings, Seattle Seahawks, and Detroit Lions? Answer: Nate Burleson When I umpired a baseball game for this guy's son, this guy complained that his son’s opponent was wearing white jerseys despite being the higher seed, and he demanded that they change. A tweet from this guy's unverified Twitter account states, “I am the elbow of Damocles” and, fittingly, was suspended for fifteen games after he elbowed Ryan McDonagh in the head from behind. He was controversially not suspended for his most famous cheap shot, a blind side hit to the head of a Boston Bruins center in 2010. For ten points, remember this guy, an agitator who spent the majority of his career with the Vancouver Canucks and ended Marc Savard's career? Answer: Matt Cooke This guy wore a “rally thong” during a 2010 postseason run, and when he began slumping the next year, fans sent him thongs in the mail. -

Union's Joel Anthony Is an NBA Champion by Julian Mckenzie

Union's Joel Anthony is an NBA Champion By Julian McKenzie After a much hyped decision, a fiery introduction, and a rise from disappointment, the 2012 version of the Miami Heat finally captured an NBA title. Among those champions, which includes the Big Three of LeBron James, Chris Bosh & Dwyane Wade, include Montreal native Joel Anthony, who returned to Montreal this week. After the 2011 NBA Finals where they were dropped in five games to the Dallas Mavericks, the Heat were able to regroup in order to reclaim the top prize over a young Oklahoma City Thunder squad in five games. “It was humbling.” Anthony described the pain of losing the 2011 Finals. “Going through the pain of losing the finals, the opportunity. All year, guys held onto [the loss]. Since the win, Anthony has been surrounded by the craziness which comes with being an NBA champion. Along with the publicity he and his teammates received in Miami, going home to his home church of Union United, he was greeted by his fans and church family, while taking part in many photo opportunities. “It’s been surreal.” Anthony says of the whole experience. “To finally win, it was a great win for us and for the city of Miami.” Despite the success, Anthony is still grounded in his values. He credits his home church, Union United. “The biggest influence was my church upbringing.” Anthony says “People see me as a laid back individual and that quiet demeanor was brought up from how I was raised. You talk about being a product of your environment and the church was my environment.” Joel has also lent his support towards the major renovation fund for Union United Church, saying he has contributed monetarily towards the campaign while aiding his mother, Erene Anthony, the head of the church’s Official Board. -

On Decemeber 2Nd, Lebron James Returned to Cleveland to Play His Old Team, the Cavaliers for the First Time Since Leaving Them for the Miami Heat

Welcome Back to Cleveland Lebron! On Decemeber 2nd, Lebron James returned to Cleveland to play his old team, the Cavaliers for the first time since leaving them for the Miami Heat. Lebron left Cleveland for Miami to join his friends Chris Bosh and Dwyane Wade in hopes of winning the NBA title that has eluded him in Cleveland. There was speculation that the Heat would surpass the all time best NBA regular season record of 72 wins and 10 losses by the 1996 Bulls. Lebron’s Miami Heat stumbled into their game against Cleveland with an 11 – 8 record, while Cleveland had a 7 – 10 record. Lebron received roaring boos and negative chants from the Cavalier fans in attendance. What does the future hold for Lebron and the Heat? Will the three super stars win an NBA championship? Or will they even make it to the playoffs? _______________________________________________________________________________________ 1. In order to still beat the Bull’s record 72 wins in a single season record, what will the Heat’s record need to be for the remainder of the season (there are 82 games in a NBA season)? 2. Find the winning percentage of the 1996 Bulls as well as the Miami Heat’s current record. Write a sentence or two comparing the two percentages. Which would you say is/was the better team? 3. The Miami Heat 2010 - 2011 season payroll is below. The team carries 15 players, but there are 18 players owed money that were on the roster at one point this season. What percent of the team’s payroll is devoted to Miami’s big three (James, Bosh, Wade)? PLAYER 2010 – 2011 SALARY LeBron James $14,500,000 Chris Bosh $14,500,000 Dwyane Wade $14,000,000 Mike Miller $5,000,000 Udonis Haslem $3,500,000 Joel Anthony $3,300,000 Eddie House $1,352,181 Zydrunas Ilgauskas $1,352,181 Juwan Howard $1,352,181 Jamaal Magloire $1,229,255 Carlos Arroyo $1,223,166 James Jones $1,069,509 Mario Chalmers $847,000 Dexter Pittman $473,604 Patrick Beverley $473,604 Da'Sean Butler $473,604 Kenny Hasbrouck $250,000 Shavlik Randolph $250,000 Jerry Stackhouse $210,339 TOTALS: $65,356,624 4. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2013 Remarks Honoring the 2012

Administration of Barack Obama, 2013 Remarks Honoring the 2012 National Basketball Association Champion Miami Heat January 28, 2013 The President. Thank you. Everybody, please have a seat. Well, today I am honored to welcome a little up-and-coming basketball team—[laughter]—to the White House called the world champion Miami Heat. Now, for many of teams that come here, this is a lot of cameras in one place. It's a little overwhelming. [Laughter] But for the Heat, this is what practice looks like. [Laughter] This is normal. I know this is the first trip for some of these players, but a few of them were here a couple of years ago for a pickup game on my birthday. Now, I'm not trying to take all the credit, Coach, but I think that it's clear that going up against me prepared them to take on Kevin Durant and Russell Westbrook. [Laughter] It sharpened their skills. It gave them the competitive edge that they needed. And I think part of the reason they came back today is they want another shot at the old guy. [Laughter] But first, I have to congratulate the Heat on their well-earned title. This team traveled a long road to get to where they are. In 2011, the Heat got all the way to the finals only to come up short. But when you fall, the real test is whether you can ignore the naysayers, pick yourself up, and come back stronger. And that's true in basketball, but it's also true in life. -

INSIDE the INSIDE LOOK at Kortemeier SPORTS EVENTS NBA FINALS Inside the Daytona 500

INSIDE THE INSIDE LOOK AT Kortemeier SPORTS EVENTS NBA FINALS Inside the Daytona 500 Inside the NBA Finals INSIDE THE NBA FINALS Inside the Olympics Inside the Super Bowl Inside the World Cup Inside the World Series THE CHILD’S WORLD ® BY TODD KORTEMEIER MOMENTUM Page intentionally blank INSIDE THE NBA FINALS BY TODD KORTEMEIER Published by The Child’s World® 1980 Lookout Drive • Mankato, MN 56003-1705 800-599-READ • www.childsworld.com Acknowledgments The Child’s World®: Mary Berendes, Publishing Director Red Line Editorial: Design, editorial direction, and production Photographs ©: Aaron M. Sprecher/AP Images, cover, 1; Icon Sports Media/Icon Sportswire, 5; Bettmann/Corbis, 6; Mark J. Terrill/AP Images, 9; Jack Smith/AP Images, 10; ZumaPress/Icon Sportswire, 12; San Antonio Express-News/ZumaPress/Icon Sportswire, 14; Kevin Reece/Icon Sportswire, 16; Icon Sportswire, 19; Tom DiPace/AP Images, 20, 24; Lynee Sladky/AP Images, 23; Sue Ogrocki/AP Images, 26, 29 Copyright © 2016 by The Child’s World® All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means without written permission from the publisher. ISBN 9781634074360 LCCN 2015946278 Printed in the United States of America Mankato, MN December, 2015 PA02283 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Todd Kortemeier is a writer and journalist from Minneapolis. He is a graduate of the University of Minnesota’s School of Journalism & Mass Communication. TABLE OF CONTENTS Fast Facts ...................................................4 Chapter 1 A Player’s Perspective: THE