Conservation Policies in Palestine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Al-Bireh Ramallah Salfit

Biddya Haris Kifl Haris Marda Tall al Khashaba Mas-ha Yasuf Yatma Sarta Dar Abu Basal Iskaka Qabalan Jurish 'Izbat Abu Adam Az Zawiya (Salfit) Talfit Salfit As Sawiya Qusra Majdal Bani Fadil Rafat (Salfit) Khirbet Susa Al Lubban ash Sharqiya Bruqin Farkha Qaryut Jalud Deir Ballut Kafr ad Dik Khirbet Qeis 'Ammuriya Khirbet Sarra Qarawat Bani Zeid (Bani Zeid al Gharb Duma Kafr 'Ein (Bani Zeid al Gharbi)Mazari' an Nubani (Bani Zeid qsh Shar Khirbet al Marajim 'Arura (Bani Zeid qsh Sharqiya) Turmus'ayya Al Lubban al Gharbi 'Abwein (Bani Zeid ash Sharqiya) Bani Zeid Deir as Sudan Sinjil Rantis Jilijliya 'Ajjul An Nabi Salih (Bani Zeid al Gharbi) Al Mughayyir (Ramallah) 'Abud Khirbet Abu Falah Umm Safa Deir Nidham Al Mazra'a ash Sharqiya 'Atara Deir Abu Mash'al Jibiya Kafr Malik 'Ein Samiya Shuqba Kobar Burham Silwad Qibya Beitillu Shabtin Yabrud Jammala Ein Siniya Bir Zeit Budrus Deir 'Ammar Silwad Camp Deir Jarir Abu Shukheidim Jifna Dura al Qar' Abu Qash At Tayba (Ramallah) Deir Qaddis Al Mazra'a al Qibliya Al Jalazun Camp 'Ein Yabrud Ni'lin Kharbatha Bani HarithRas Karkar Surda Al Janiya Al Midya Rammun Bil'in Kafr Ni'ma 'Ein Qiniya Beitin Badiw al Mus'arrajat Deir Ibzi' Deir Dibwan 'Ein 'Arik Saffa Ramallah Beit 'Ur at Tahta Khirbet Kafr Sheiyan Al-Bireh Burqa (Ramallah) Beituniya Al Am'ari Camp Beit Sira Kharbatha al Misbah Beit 'Ur al Fauqa Kafr 'Aqab Mikhmas Beit Liqya At Tira Rafat (Jerusalem) Qalandiya Camp Qalandiya Beit Duqqu Al Judeira Jaba' (Jerusalem) Al Jib Jaba' (Tajammu' Badawi) Beit 'Anan Bir Nabala Beit Ijza Ar Ram & Dahiyat al Bareed Deir al Qilt Kharayib Umm al Lahim QatannaAl Qubeiba Biddu An Nabi Samwil Beit Hanina Hizma Beit Hanina al Balad Beit Surik Beit Iksa Shu'fat 'Anata Shu'fat Camp Al Khan al Ahmar (Tajammu' Badawi) Al 'Isawiya. -

Ramallah and Al-Bireh Governorate (2030)

Spatial Development Strategic Framework الخطة التنموية المكانية االستراتيجية for Ramallah and Al-Bireh Governorate لمحافظة رام اهلل والبيرة (2030) (2030) Summary ملخـــص دولة فلسطني State of Palestine Spatial Development Strategic Framework for Ramallah and Al-Bireh Governorate (2030) Executive Summary March 2020 Ramallah & Al-Bireh Governorate Spatial Development Strategic Framework (2030) Disclaimer This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union under the framework of the project entitled: “Fostering Tenure Security and Resilience of Palestinian Communities through Spatial-Economic Planning Interventions in Area C (2017 – 2020)” , which is managed by the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat). The Ministry of Local Government, and the Ramallah and Al-Bireh Governorate are considered the most important partners in preparing this document. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the author and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union. Furthermore, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used on the maps presented do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Contents Disclaimer 2 Contents 3 Acknowledgments 4 Ministerial Foreword Hono. Minister of Local Government 6 Foreword Hono. Governor of Ramallah and Al-Bireh 7 This Publication has been prepared by Arabtech Jardaneh Consultative Company (AJPAL). The publication has been produced in a participatory approach and with substantial inputs from many local -

Locality Profiles and Needs Assessment in the Ramallah & Al

Locality Profiles and Needs Assessment in the Ramallah & Al Bireh Governorate ARIJ welcomes any comments or suggestions regarding the material published herein and reserves all copyrights for this publication. This publication is available on the project’s homepage: http://proxy.arij.org/vprofile/ramallah and ARIJ homepage: http://www.arij.org Copyright © The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem (ARIJ) 2014 Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) and civil society organizations for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. Editors Jad Isaac Roubina Ghattas Nader Hrimat Contributors Iyad Khalifeh Elia Khalilieh Ayman Abu Zahra Juliette Bannoura Enas Bannourah Nadine Sahouri Hamza Halaybeh Flora Al-Qassis Ronal El Zughayyar Anas Al Sayeh Poppy Hardee Issa Zboun Jane Hilal Suhail Khalilieh Table Of Contents PART ONE: Introduction................................................................................................................ 6 Locality Profiles and Needs Assessment in Ramallah & Al Bireh Governorate....................7 1.1. Project Description and Objectives:.................................................................... 7 1.2. Project Activities:................................................................................................ -

'Abwein Town Profile

‘Abwein Town Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 2012 Palestinian Localities Study Ramallah Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, town committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 2 Palestinian Localities Study Ramallah Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, town, and village in the Ramallah Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in Ramallah Governorate, which aims at depicting the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in developing the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Town Profiles and Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Town Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the needed programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current unsecure political, economic and social conditions in Ramallah Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze, and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in Ramallah Governorate. -

Bani Zeid Ash Sharqiya Town Profile

Bani Zeid ash Sharqiya Town Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 2012 Palestinian Localities Study Ramallah Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 2 Palestinian Localities Study Ramallah Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, town, and village in the Ramallah Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in Ramallah Governorate, which aims at depicting the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in developing the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the needed programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current unsecure political, economic and social conditions in Ramallah Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze, and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in Ramallah Governorate. -

Gaza Strip West Bank

Afula MAP 3: Land Swap Option 3 Zububa Umm Rummana Al-Fahm Mt. Gilboa Land Swap: Israeli to Palestinian At-Tayba Silat Al-Harithiya Al Jalama Anin Arrana Beit Shean Land Swap: Palestinian to Israeli Faqqu’a Al-Yamun Umm Hinanit Kafr Dan Israeli settlements Shaked Al-Qutuf Barta’a Rechan Al-Araqa Ash-Sharqiya Jenin Jalbun Deir Abu Da’if Palestinian communities Birqin 6 Ya’bad Kufeirit East Jerusalem Qaffin Al-Mughayyir A Chermesh Mevo No Man’s Land Nazlat Isa Dotan Qabatiya Baqa Arraba Ash-Sharqiya 1967 Green Line Raba Misiliya Az-Zababida Zeita Seida Fahma Kafr Ra’i Illar Mechola Barrier completed Attil Ajja Sanur Aqqaba Shadmot Barrier under construction B Deir Meithalun Mechola Al-Ghusun Tayasir Al-Judeida Bal’a Siris Israeli tunnel/Palestinian Jaba Tubas Nur Shams Silat overland route Camp Adh-Dhahr Al-Fandaqumiya Dhinnaba Anabta Bizzariya Tulkarem Burqa El-Far’a Kafr Yasid Camp Highway al-Labad Beit Imrin Far’un Avne Enav Ramin Wadi Al-Far’a Tammun Chefetz Primary road Sabastiya Talluza Beit Lid Shavei Shomron Al-Badhan Tayibe Asira Chemdat Deir Sharaf Roi Sources: See copyright page. Ash-Shamaliya Bekaot Salit Beit Iba Elon Moreh Tire Ein Beit El-Ma Azmut Kafr Camp Kafr Qaddum Deir Al-Hatab Jammal Kedumim Nablus Jit Sarra Askar Salim Camp Chamra Hajja Tell Balata Tzufim Jayyus Bracha Camp Beit Dajan Immatin Kafr Qallil Rujeib 2 Burin Qalqiliya Jinsafut Asira Al Qibliya Beit Furik Argaman Alfe Azzun Karne Shomron Yitzhar Itamar Mechora Menashe Awarta Habla Maale Shomron Immanuel Urif Al-Jiftlik Nofim Kafr Thulth Huwwara 3 Yakir Einabus -

Imagining the Border

A WAshington institute str Ategic r eport Imagining the Border Options for Resolving the Israeli-Palestinian Territorial Issue z David Makovsky with Sheli Chabon and Jennifer Logan A WAshington institute str Ategic r eport Imagining the Border Options for Resolving the Israeli-Palestinian Territorial Issue z David Makovsky with Sheli Chabon and Jennifer Logan All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2011 The Washington Institute for Near East Policy Published in 2011 in the United States of America by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050, Washington, DC 20036. Design by Daniel Kohan, Sensical Design and Communication Front cover: President Barack Obama watches as Israeli prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu and Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas shake hands in New York, September 2009. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak) Map CREDITS Israeli settlements in the Triangle Area and the West Bank: Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, 2007, 2008, and 2009 data Palestinian communities in the West Bank: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 2007 data Jerusalem neighborhoods: Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, 2008 data Various map elements (Green Line, No Man’s Land, Old City, Jerusalem municipal bounds, fences, roads): Dan Rothem, S. Daniel Abraham Center for Middle East Peace Cartography: International Mapping Associates, Ellicott City, MD Contents About the Authors / v Acknowledgments / vii Settlements and Swaps: Envisioning an Israeli-Palestinian Border / 1 Three Land Swap Scenarios / 7 Maps 1. -

Palestinian Economy and the Prospects for Its Recovery

40462 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized .UMBER $ECEMBER %CONOMIC-ONITORING2EPORTTOTHE!D(OC,IAISON#OMMITTEE ANDTHE0ROSPECTSFORITS2ECOVERY 4HE0ALESTINIAN%CONOMY 7EST"ANKAND'AZA 4HE7ORLD"ANK Contents FOREWORD – THE CONTEXT FOR THIS REPORT…………………………….……….i 1 – SUMMARY ASSESSMENT AND RECOMMENDATIONS………………………………1 I – THE NEED FOR RAPID ECONOMIC GROWTH…………………………………….1 II – GROWTH IN 2005 – ENCOURAGING BUT INCONCLUSIVE………………………..1 III – CREATING THE PRECONDITIONS FOR ECONOMIC RECOVERY: A PROGRESS REPORT………………………………………………..………….………….....2 IV – NEXT STEPS……………………………………………………………………5 2 – THE STATE OF THE PALESTINIAN ECONOMY: JANUARY THROUGH SEPTEMBER 2005……………………………………………6 I – OVERVIEW............................................................................................................................6 II – ECONOMIC OUTPUT…………………………………………………………….6 III – FISCAL AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS………………………………………7 IV – LABOR MARKET TRENDS……………………………………………………….9 3 – ECONOMIC RECOVERY: PRECONDITIONS AND PROSPECTS……………………10 I – MOVEMENT AND ACCESS………………………………………………………10 II – PALESTINIAN GOVERNANCE…………………………………………………..16 III – GROWTH PROSPECTS AND THE ROLE OF THE DONORS……………………….22 MAPS – GAZA, WEST BANK…………………………………………………………..24 ANNEX 1 – ECONOMIC SCENARIOS………………………………………………….26 ANNEX 2 – INDICATORS OF ECONOMIC REVIVAL…………………………………..29 ANNEX 3 – “TURNING THE CORNER” .……………………………………………..35 ANNEX 4 – AGREEMENT ON MOVEMENT AND ACCESS…………………………….39 ENDNOTES………………...………………………………………………………...44 -

Humanitarian Bulletin Opt Monthly REPORT January 2015

HUManitarian BULLETIN oPt MONTHLY REPORT JanuarY 2015 HIGHLIGHTS Overview ● All public employees in the Gaza Overview: worrisome deterioration in the IN THIS ISSUE Strip affected by the non-payment of Gaza Situation 2015 Strategic Response Plan salaries, further undermining services launched .......................................................3 and livelihoods. Concern over further deterioration This month’s Humanitarian Bulletin focuses in food security and quality of services in the Gaza Strip ..........................................4 ● Cash assistance to some 100,000 again on the deteriorating situation in the Gaza Gaza: lack of comprehensive internally displaced people in Gaza Strip. The longstanding economic crisis in Gaza registration and profiling of IDPs suspended due the unavailability of continueS to undermine was further exacerbated in January by Israel’s response efforts ........................................9 funds pledged by donors. decision to freeze the transfer of tax revenues Winter weather results in casualties, flooding and Additional displacement ● Record number of olive trees and it collects on behalf of the Palestinian Authority in the Gaza Strip ...................................... 13 saplings reportedly vandalized by (PA), in retaliation for the Palestinian accession Ongoing accountability initiatives for alleged violations during Israeli settlers during January. to the International Criminal Court. As a result, Gaza hostilities ........................................ 14 West Bank: Largest Number of -

Print), 2369-5994 (Online) Copyright © the Author(S)

Ghanem, M. et al. The Canadian Journal for Middle East Studies July 2017, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 78- 92 ISSN: 2369-5986 (Print), 2369-5994 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2017. All Rights Reserved Published by Institute for Middle East Studies, Canada DOI: Socio - Economic - Environmental Impact on Spring water in Western Ramallah Catchments Marwan Ghanem*, Waseem Ahmad**, Farah Sawaftah***, and Yacoub Keilan**** *Birzeit University, P.O.Box 14, Ramallah - Palestine, [email protected] **Ministry of Health, Ramallah - Palestine, [email protected] ***Ministry of Agriculture, Ramallah - Palestine, [email protected] ****Ministry of Agriculture, Ramallah - Palestine, [email protected] Abstract The socio economic environmental impact of using the spring water in the Central Western Ramallah - Palestine Catchments was studied. The study concentrated on the villages that contains large discharge springs in the catchments. A total of 152 questionnaires were filled and analyzed in a field survey campaign during December month 2015. The study targeted questions related to socio economic, land use area around the springs, the situation of the springs and discharge quantities. The questionnaires have been analyzed through SPSS Statistics program. As a result, access to these springs is challenging and at times may even be dangerous. As most of the springs are located at some distance from residential areas they are also not located near cesspits which are the common form of wastewater disposal in rural areas. Pesticides and fertilizers used on agricultural land in the vicinity of spring was ranked first as a pollution source, followed by human activities namely recreation around the springs and wastewater. -

An Update on Palestinian Movement, Access and Trade in the West Bank and Gaza

World Bank Technical Team Report, August 15, 2006 40461 An Update on Palestinian Movement, Access and Trade in the West Bank and Gaza Summary Public Disclosure Authorized Background This paper provides an updated assessment of movement and access for goods and people in WBG1, which was initiated by the World Bank after the December 2004 Ad Hoc Liaison Committee Meeting when all parties (including the Government of Israel and the Palestinian Authority) agreed that Palestinian economic revival was essential, that it required a major dismantling of today’s closure regime and that closure needed to be addressed from several perspectives at once. In today’s environment of confrontation and heightened risk, movement and access controls have increased and earlier relaxations have been reversed. However, the relationship between Palestinian economic revival and stability and Israeli security remain unarguable and of fundamental importance to both societies’ well-being. Recent initiatives by US-security advisor General Dayton to significantly enhance the security of the Karni crossing between Gaza and Israel in order to ensure an efficient and predicable corridor for trade recognizes this relationship. Public Disclosure Authorized Movement of goods Between Gaza and Israel Growth prospects for the West Bank and Gaza depend critically on its openness to trade. Prior to the Intifada, the flow of cargo into and out of Gaza was largely determined by market demand, with most cargo moving in convoys or through the (then) relatively simple Erez crossing. Today, all cargo flows between Israel and Gaza must be channeled through the Karni crossing point. From a low base of only 43 export trucks per day in the six months prior to the Israeli disengagement from Gaza, actual daily export numbers through mid-June 2006 have fallen to less than 25 trucks a day. -

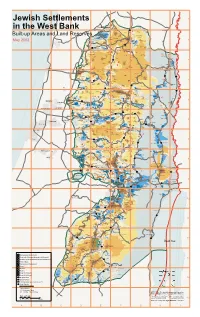

Jewish Settlements in the West Bank

1 Jewish Settlements Zububa Ti'nnik Rummana Umm Al-Fahm Al-Jalama Arabbuna in the West Bank At-Tayba 'Anin Silat Al-Harithiya 60 Arrana Faqqu'a Bet She'an Al-Yamun Deir Ghazala Dahiyat Sabah Al-Kheir Tal Menashe Umm Ar-Rihan Hinnanit Mashru' Beit Qad Built-up Areas and Land Reserves Kh. 'Abdallah Al-Yunis Dhaher Al-Malih Kafr Dan Shaqed 'Araqa Beit Qad Jalbun Rekhan Al-Hashimiya Tura-al-Gharbiya At-Tarem Barta'a Ash Sharqiya Jenin RC Jenin Nazlat Ash-Sheikh Zeid 2 Umm Dar Kaddim Kafr Qud Birqin Ganim Deir Abu-Da'if May 2002 Dhaher Al-'Abed Hadera Akkaba Ya'bad Kufeirit Qeiqis Zabda 'Arab As-Suweitat 60 Umm at-Tut Qaffin Imreiha Jalqamus Ash-Shuhada 585 Mevo Dotan Hermesh Al-Mughayyir Al-Mutilla Nazlat 'Isa Qabatiya Baqa Ash-Sharqiya An-Nazla Ash-Sharqiya Bir Al-Basha Ad-Damayra An-Nazla Al-Wusta Telfit Arraba Mirka Bardala An-Nazla Al-Gharbiya Fahma Al-Jadida Ein El-Beida Misiliya Fahma Raba Zeita Kardala Seida Az-Zababida Zawiya Al-Kufeir Mehola Attil Kfar Ra'i 60 Sir 3 Illar Ajja Anza Sanur Meithalun Shadmot Mehola Deir Al-Ghusun Ar-Rama Al-Jarushiya Tayasir Al-'Aqaba Al-Farisiya Sa Nur Nahal Rotem Al-Judeida Siris Tubas Netanya Shuweika Al-'Attara Jaba' Al-Malih Iktaba Bal'a Nahal Bitronot / Brosh Tulkarm RC Nur Shams RC Nahal Maskiyot Kafr Rumman Silat Adh-Dhahr Al-Fandaqumiya Dhinnaba 'Anabta Tulkarm Homesh Ras Al-Far'a Kafr al-Labad Bizzariya Burqa Yasid Al-Far'a RC Beit Imrin 'Izbat Shufa 578 90 Ramin Tammun Avne Hefez Al-Far'a Far'un Kafa Nisf Jubeil Enav Sabastiya 4 Shufa Talluza 57 Ijnisinya Kh.