Donagh Macdonagh Ballads of Nineteen-Sixteen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to the Collection of Irish Antiquities

NATIONAL MUSEUM OF SCIENCE AND ART, DUBLIN. GUIDE TO THE COLLECTION OF IRISH ANTIQUITIES. (ROYAL IRISH ACADEMY COLLECTION). ANGLO IRISH COINS. BY G COFFEY, B.A.X., M.R.I.A. " dtm; i, in : printed for his majesty's stationery office By CAHILL & CO., LTD., 40 Lower Ormond Quay. 1911 Price One Shilling. cj 35X5*. I CATALOGUE OF \ IRISH COINS In the Collection of the Royal Irish Academy. (National Museum, Dublin.) PART II. ANGLO-IRISH. JOHN DE CURCY.—Farthings struck by John De Curcy (Earl of Ulster, 1181) at Downpatrick and Carrickfergus. (See Dr. A. Smith's paper in the Numismatic Chronicle, N.S., Vol. III., p. 149). £ OBVERSE. REVERSE. 17. Staff between JiCRAGF, with mark of R and I. abbreviation. In inner circle a double cross pommee, with pellet in centre. Smith No. 10. 18. (Duplicate). Do. 19. Smith No. 11. 20. Smith No. 12. 21. (Duplicate). Type with name Goan D'Qurci on reverse. Obverse—PATRIC or PATRICII, a small cross before and at end of word. In inner circle a cross without staff. Reverse—GOAN D QVRCI. In inner circle a short double cross. (Legend collected from several coins). 1. ^PIT .... GOANDQU . (Irish or Saxon T.) Smith No. 13. 2. ^PATRIC . „ J<. ANDQURCI. Smith No. 14. 3. ^PATRIGV^ QURCI. Smith No. 15. 4. ^PA . IOJ< ^GOA . URCI. Smith No. 16. 5. Duplicate (?) of S. No. 6. ,, (broken). 7. Similar in type of ob- Legend unintelligible. In single verse. Legend unin- inner circle a cross ; telligible. resembles the type of the mascle farthings of John. Weight 2.7 grains ; probably a forgery of the time. -

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

From Celtic Twilight to Revolutionary Dawn: the Irish Review, 1911-14

From Celtic Twilight to Revolutionary Dawn The Irish Review 1911-1914 By Ed Mulhall The July 1913 edition of The Irish Review , a monthly magazine of Irish Literature, Art and Science, leads off with an article " Ireland, Germany and the Next War" written under the pseudonym " Shan Van Vocht ". The article is a response to a major piece written by Arthur Conan Doyle, the author of the Sherlock Holmes books and a noted writer on international issues, in the Fortnightly Review of February 1903 called "Great Britain and the Next War". Shan Van Vocht takes issue with a central conclusion of Doyle's piece that Ireland's interests are one with Great Britain if Germany were to be victorious in any conflict. Doyle writes: "I would venture to say one word here to my Irish fellow- countrymen of all political persuasions. If they imagine that they can stand politically or economically while Britain falls, they are woefully mistaken. The British Fleet is their one shield. If it be broken, Ireland will go down. They may well throw themselves heartily into the common defense, for no sword can transfix England without the point reaching Ireland behind her." However The Irish Review author proposes to show that "Ireland, far from sharing the calamities that must necessarily fall on Great Britain from defeat by a Great Power, might conceivably thereby emerge into a position of much prosperity." The contents page of the July 1913 issue of The Irish Review In supporting this provocative stance the author initially tackles two aspects of the accepted British view of Ireland's fate under these circumstances: that Ireland would remain tied with Britain under German rule or that she might be annexed by the victor. -

Good Grade. 6. 1916 Shilling

1. 1696 crown. 45. Qty. pennies etc. 3.3 kg. 2. 2 x 1937 crown. 46. Boxed set of 4 crowns. 3. 1836 ½ crown. 47. 1914 half crown – better grade. 4. 2 x 1935 crowns. 48. 1889 crown. 5. 1918 Rupee – good grade. 49. 1889 crown. 6. 1916 shilling – good grade. 50. USA 1922 Dollar. 7. 1927 wreath crown. 51. Enamel George 111 crown. 8. USA silver dollar 1922. 52. 1922 Australia florins. 9. Silver Death of Victoria medallion. 53. 1939 penny – good grade and ½ 10. 1806 penny – good grade. penny. 11. 2 x 1951 crown and 1953 crown. 54. Proof silver £1 coins. 12. 3 x 1951 crowns. 55. 1998 proof set piedfort £1 coin. 13. 1895 crown. 56. 1993 proof set piedfort £1 coin. 14. 1943 ½ Dollar. 57. 2001 proof set piedfort £1 coin. 15. 3 piece enamel type coin jewellery. 58. 1992 proof silver piedfort 50p. 16. Box medallion. 59. Good grade 1891 USA dime. 17. Cigarette cards. 60. Good grade 1836 Groat. 18. Bank notes etc. 61. Boxed set of 3 D.Day crowns. 19. Tin of coins. 62. 2 proof silver 10p. 1992. 20. Purse of coins. 63. Proof 2001 £5 coin. 21. 1857 USA 1 cent. 64. 1988 proof set UK. 22. Cheltenham penny token 1812. 65. 1989 proof set UK. 23. 3 tokens. 66. 1953 proof set. 24. 18th century Irish ½ pennies. 67. 1935 and 1937 crown. 25. 1813 IOM penny. 68. 2 x 1935 crown. 26. 3 Victorian ½ farthings. 69. 1889 crown. 27. Victoria farthings 1839 onwards. 70. 1889 crown. 28. Canada 25d. -

Exchange of Irish Coins

IR£ COINS ONLY Irish Pound coins can be submitted for value exchange via the drop box located at the Central Bank of Ireland in North Wall Quay or by post to: Central Bank of Ireland, PO Box 61, P3, Sandyford, Dublin 16. Please note submissions cannot be dropped in to the Sandyford address. Please sort your submission in advance as follows: Submissions must include: 1. Completed form 2. Bank account details for payment 3. A copy of photographic ID for submissions over €100 More information: See the “Consumer Hub” area on www.centralbank.ie, email [email protected], or call the Central Bank on +353 1 2245969. SUBMISSION DETAILS Please give details of the COIN(S) enclosed Quantity OFFICE USE Quantity OFFICE USE Denomination Denomination Declared ONLY Declared ONLY ¼d (Farthing) ½p (Halfpenny) ½d (Halfpenny) 1p (Penny) 1d (Penny) 2p (Two pence) 3d (Threepence) 5p (Five pence) 6d (Sixpence) 10p (Ten pence) 1s (Shilling) 20p (Twenty pence) 2s (Florin) 50p (Fifty pence) 2/6 (Half crown) £1 (One pound) 10 s (Ten Shilling) TOTAL QUANTITY Modified 16.12.19 IR£ COINS ONLY Failure to complete the form correctly will result in delay in reimbursement. Please use BLOCK CAPITALS throughout this form. Important information for submissions by companies: Please provide your CRO number: , For submissions over €100, please submit a redacted bank statement in the company name for the nominated bank account instead of photo ID. Applicant Details Applicant’s Full Name Tel Number Address Email Address For submissions over €100: Have you attached the required ID? yes To protect your personal information, please fold completed form along dotted line ensuring this side faces inward. -

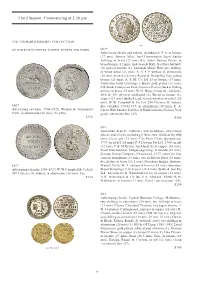

Third Session, Commencing at 2.30 Pm

Third Session, Commencing at 2.30 pm THE HOWARD BROWN COLLECTION part OF AUSTRALIAN CHECKS, TOKENS, TICKETS AND PASSES 602* Advertising checks and tokens, including A. F. A. in bronze (27 mm), Barney Allen, Turf Commission Agent Lucky farthing, in brass (23 mm) (4)), Allens Battery Patent, in brass/bronze (32 mm), Anderson & Hall, Jewellers Adelaide (26 mm) in bronze (2), Annabels Music Hall, one shilling, in white metal (23 mm), A. S. F. P. uniface in aluminium (18 mm), bronze (26 mm), Assam & Darjeeling Teas, gilded bronze (26 mm), A. S. M. Co Ltd 13 in bronze (17 mm), Australian Gold Exchange 3 Bucks gold plated (32 mm), E.R.Banks Enterprises Perth, bronze (26 mm), Becker shilling uniface in brass (25 mm), W. H. Bruce, Groat St., Adelaide, 28/6 & 30/- silvered cardboard (2), Bovril in bronze (2), copper (21 mm), Bullock Lade Scotch whiskey in nickel (26 mm), W. W. Campbell & Co Ltd, 240 Clarence St, Sydney, 600* disc calendar 1904-1927, in aluminium (38 mm), E. A. Advertising calendar, 1904-1925, Watson & Gutmann's Carter Watchmaker Jeweller, St Kilda in brass (25 mm). Very Perth, in aluminium (38 mm). Very fi ne. good - extremely fi ne. (23) $150 $200 603 Australian dealers, collectors and medallists, advertising tokens and checks, including P. Bickerton, Ballarat for fi fty cents (2) in gilt (32 mm), Cut Price Coins Queensland, 1997, in nickel (26 mm), P. J. Downie Pty Ltd, 1988, in gilt (32 mm), P & M Eccles, Auckland (5) in copper (20 mm), Nicol International, badges engraving, in bronze (36 mm), Scandia Stamp Company, Chatswood, 1977, token for fi fty cents in aluminium (24 mm), two dollars in brass (24 mm), fi ve dollars in brass (28.5 mm), Sheridans Badges, Buttons, 601* Medals, Perth, W. -

Call No. Responsibility Item Publication Details Date Note 1

Call no. Responsibility Item Publication details Date Note TKNC0001 Roberts, H. Song, to a gay measure Dublin: printed at the Dolmen 1951 "200 copies." Neville Press TKNC0002 Promotional notice for Travelling tinkers, a book of Dolmen Press ballads by Sigerson Clifford TKNC0003 Promotional notice for Freebooters by Mauruce Kennedy Dolmen Press TKNC0004 Advertisement for Dolmen Press Greeting cards &c Dolmen Press TKNC0005 The reporter: the magazine of facts and ideas. Volume July 16, 1964 contains 'In the 31 no. 2 beginning' (verse) by Thomas Kinsella TKNC0006 Clifford, Travelling tinkers Dublin: Dolmen Press 1951 Of one hundred special Sigerson copies signed by the author this is number 85. Insert note from Thomas Kinsella. TKNC0007 Kinsella, Thomas The starlit eye / Thomas Kinsella ; drawings by Liam Dublin: Dolmen Press 1952 Set and printed by hand Miller at the Dolmen Press, Dublin, in an edition of 175 copies. March 1952. (p. [8]). TKNC0008 Kinsella, Thomas Galley proof of Poems [Glenageary, County Dublin]: 1956 Galley proof Dolmen Press TKNC0009 Kinsella, Thomas The starlit eye / Thomas Kinsella ; drawings by Liam Dublin : Dolmen Press 1952 Of twenty five special Miller copies signed by the author this is number 20. Set and printed by hand at the Dolmen Press, Dublin, in an edition of 175 copies. March 1952. TKNC0010 Promotional postcard for Love Duet from the play God's Dolmen Press gentry by Donagh MacDonagh TKNC0011 Irish writing. No. 24 Special issue - Young writers issue Dublin Sep-53 1 Thomas Kinsella Collection Listing Call no. Responsibility Item Publication details Date Note TKNC0012 Promotional notice for Dolmen Chapbook 3, The perfect Dolmen Press 1955 wife a fable by Robert Gibbings with wood engravings by the author TKNC0013 Pat and Mick Broadside no. -

Collector's Checklist for Foreign Type Coins Made by United

Liberty Coin Service Collector’s Checklist for Foreign Type Coins Made by United States Government Mints (1876-2000) Argentina Purchase Grade Price Denomination Composition Fine Wt. KM# Date Mintmark Mint Date P D S O W M 5 Centavos Copper Nickel 34 1919-20 10 Centavos Copper Nickel 35 1919-20 20 Centavos Copper Nickel 36 1919-20 These were blank planchets produced by the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia. Coins were not actually struck by the U.S. Mint. Australia 3 Pence .925 Silver .0419 37 1942-44 D,S 6 Pence .925 Silver .0838 38 1942-44 D,S Shilling .925 Silver .1680 39 1942-44 S Florin .925 Silver .3363 40 1942-44 S Belgian Congo 2 Francs Brass 25 1943 None Belgium 2 Francs Steel 133 1944 None Bolivia 10 Centavos Zinc 179a 1942 None 20 Centavos Zinc 183 1942 None 50 Centavos Bronze 182a.1 1942 None Canada 10 Cents Nickel 73 1968 None China Dollar .880 Silver .7555 345 (1934) None Taiwan Yuan Copper Nickel Zinc 536 (1973) None (Republic of China) 5 Yuan Copper Nickel 548 (1973) None Colombia Purchase Grade Price Denomination Composition Fine Wt. KM# Date Mintmark Mint Date P D S O W M Centavo Copper Nickel 275 1920-38 None 2 Centavos Copper Nickel 198 1920-38 None 5 Centavos .666 Silver .0268 191 1902 None 5 Centavos Copper Nickel 199 1933-46 None 50 Centavos .835 Silver .3356 192 1902 None 50 Centavos .900 Silver .3617 274 1916-34 None Costa Rica 2 Centimos Copper Nickel 144 1903 None 5 Centimos .900 Silver .0289 145 1905-14 None 10 Centimos .900 Silver .0578 146 1905-14 None 50 Centimos .900 Silver .2893 143 1905-14 None Colon Csp. -

Brian Ó Nualláin/O'nolan

Brian Ó Nualláin/O’Nolan Scholarly Background & Foreground* Breandán Ó Conaire St Patrick’s College, Dublin City University ‘Ní fhéadaim cuimhneamh ar aon scríbhneoir mór anois a bhféadfá fear léannta a thabhairt air’ (I cannot think of any major writer at present who could be called a man of learning). – Seán Ó Ríordáin 1 ‘Brian Ó Nualláin, afterwards alias Myles na gCopaleen, alias Flann O’Brien, and, as it turned out, the most gifted bilingual genius of half a century’ – Cearbhall Ó Dálaigh, Irish President (1974–76)2 Family Background From his early years, Brian O’Nolan lived in a family environment in which education, literature, the Irish language, culture, and learning held significant importance. This milieu was reflected in the skills, talents, and accomplishments of members of the extended family. His paternal grandfather Daniel Nolan from Munster was a national teacher and taught music at the Model School in Omagh, Co. Tyrone. He was an excellent singer and an accomplished violinist. He had a special fondness for theatre and opera, performances of which he frequently attended with his young wife. A special concert was organised in his honour in Omagh prior to his transfer to Belfast in the early 1880s. In July 1867 Daniel married Jane Mellon3 a former pupil at the Omagh school and fourth daughter of James Mellon, a strong farmer from Eskeradooey in Co. Tyrone. The marriage took place at Knockmoyle Catholic Church in Cappagh parish where Jane was born. The parish priest, Rev. Charles McCauley, was the celebrant. In the national census entries for 1901 and for 1911, when Jane, also known as ‘Sinéad,’ lived with the O’Nolan family in Strabane, her competence in both Irish and English was recorded. -

Downloaded from Downloaded on 2020-06-06T01:34:25Z Ollscoil Na Héireann, Corcaigh

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title A cultural history of The Great Book of Ireland – Leabhar Mór na hÉireann Author(s) Lawlor, James Publication date 2020-02-01 Original citation Lawlor, J. 2020. A cultural history of The Great Book of Ireland – Leabhar Mór na hÉireann. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Rights © 2020, James Lawlor. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/10128 from Downloaded on 2020-06-06T01:34:25Z Ollscoil na hÉireann, Corcaigh National University of Ireland, Cork A Cultural History of The Great Book of Ireland – Leabhar Mór na hÉireann Thesis presented by James Lawlor, BA, MA Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy University College Cork The School of English Head of School: Prof. Lee Jenkins Supervisors: Prof. Claire Connolly and Prof. Alex Davis. 2020 2 Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 4 Declaration .......................................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ 6 List of abbreviations used ................................................................................................... 7 A Note on The Great -

Catalogue 42 Courtwood Books Catalogue 42 Courtwood Books Catalogue 42 C OURTWOOD B OOKS 1 A

Courtwood Books Catalogue 42 Courtwood Books Catalogue 42 Courtwood Books Catalogue 42 C OURTWOOD B OOKS 1 A. E. (Russell, George). Ireland and the Empire at the Court of Conscience. €35.00 ood tw r The Talbot Press, Dublin 1921. 1st separate edition. Post 8vo. (1) + 2-16 pp. Integral u o s k o C o s b Phone: 057 8626384 Courtwood Books, wrapper title. A few small chips & last page somewhat soiled, else a good clean [U.K. 00 353 57 8626384] Vicarstown, copy. Scarce. Denson 42. First published in the Manchester Guardian in September 1921. Email: [email protected] Stradbally, 2 A. E. (Russell, George). The Avatars - A Futurist Fantasy. €65.00 Website: courtwoodbooks.ie Co. Laois. Macmillan, New York 1933. 1st US edition. Crown 8vo. viii + 188 + (2 advts) pp. Blue cloth with lettering in gilt. Trace of rubbing at cover extrems, else a very nice bright copy. Denson A52a. Fifteen hundred copies printed. CATALOGUE 42 3 (Agriculture interest). Stephens, Henry. A Manual of Practical Draining. €75.00 William Blackwood, London 1847. 2nd edition, corrected & enlarged. Medium 8vo. The codeword for this catalogue is "KINCH" which means "please send from xvi + 160 + 8 advts pp. Numerous in-text illustrations throughout. Original green catalogue 42 the following item(s) ..." cloth with paper label on front panel. A very nice clean copy with just a little wear on cover extrems. Scarce in this condition. 4 Allen, F. M. (Downey, Edmund). From the Green Bag. €60.00 The books are described, and faults where they exist, are noted as accurately as Ward & Downey, London 1889. -

COURT LAUNDRY English Have, As a Knightly Nation, Lost Our · 68A Harcourt Street, DUBLI • ~Xeepl It Brinr,-S Gold, Could for One Mom •Nt Spurs

NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF IRELAND Archives are subject to copyright and should not be copied or reproduced without the written permission of the Director of the National Archives l 4- ( 63 S. 2( ) 7 ~t (1.858. )Wt.5333-66.4000. 12j14.A.T.&Co.,Ltd. (6559. )Wt. 3~03-96 .2 0 , 000.8 I 15. ........,.___ D.lVLP.______' ._1 Telegrams : " DAMP, DUBLIN." '. Telephone No. 22. DUBLIN lVIETROPOLITAN POLICE. .. • + lDetecttt"e lDepartment, ' . Dublin; 9th. December, _ 191 5 . SubJ·ect, _ ____MO_ -VEME_ NTS OF DUBLIN EXTREMISTS. I beg to report that on the 8th. Inst., a ~~ the undermentioned extremists were observed ~ moving about and associating ith each other as follows :- i th Thomas J. Clarke, 75·, Parnell ·St. ; '-. Major_John McBride and Joseph Murray for a ,. quarter of an hour between 12 & 1 p.m. F. " Fahy for half an hour from 1 p. m. Pierce ~. Beasley from 1. 30. to 1. 45 p.m. J. J. Buggy for twent_y minutes between 8 & 9 p. m. William O'Leary Curtis for a quarter of-an ho·ur from 9 p. m. ~- Jv1 . o·•-Hanrahan at Volunteer Office, 2, Dawson Street at 11 a. 1n . ,. Ed. De Valera and M. J. O'Rahilly 1n• company at Grafton Street between 1 & 2 p.m. C. Collins, G. P. 0., P. O'Keeffe,G.P.O., and John McDermott in conversation in D'Olier Street at 3. 45 p. m. P. Ryan and E. O'Duffy at 2, Dawson St., between 3 & 4 p~ - m. .. ~L. M. J. O'Rahilly, John McDermott, James , O'Connor, .P.