Benjamin Franklin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Was 'The Enlightenment'? We Hear About It All the Time. It Was A

What Was ‘The Enlightenment’? We hear about it all the time. It was a pivotal point in European history, paving the way for centuries of history afterward, but what was ‘The Enlightenment’? Why is it called ‘The Enlightenment’? Why did the period end? The Enlightenment Period is also referred to as the Age of Reason and the “long 18th century”. It stretched from 1685 to 1815. The period is characterized by thinkers and philosophers throughout Europe and the United States that believed that humanity could be changed and improved through science and reason. Thinkers looked back to the Classical period, and forward to the future, to try and create a trajectory for Europe and America during the 18th century. It was a volatile time marked by art, scientific discoveries, reformation, essays, and poetry. It begun with the American War for Independence and ended with a bang when the French Revolution shook the world, causing many to question whether ideas of egalitarianism and pure reason were at all safe or beneficial for society. Opposing schools of thought, new doctrines and scientific theories, and a belief in the good of humankind would eventually give way the Romantic Period in the 19th century. What is Enlightenment? Philosopher Immanuel Kant asked the self-same question in his essay of the same name. In the end, he came to the conclusion: “Dare to know! Have courage to use your own reason!” This was an immensely radical statement for this time period. Previously, ideas like philosophy, reason, and science – these belonged to the higher social classes, to kings and princes and clergymen. -

Tobias Heinrich Friedrich Schlichtegroll's Nekrolog

Pour citer cet article : Heinrich, Tobias, « Friedrich Schlichtegroll’s Nekrolog. Enlightenment Biography », Les Grandes figures historiques dans les lettres et les arts [en ligne], n° 6 (2017), URL : http://figures-historiques.revue.univ-lille3.fr/6-2017-issn-2261-0871/. Tobias Heinrich New College, University of Oxford Friedrich Schlichtegroll’s Nekrolog. Enlightenment Biography.1 Let the dead bury the dead. We want to see the deceased as living beings, to rejoice in their lives, including their lives as they continue after their demise, and for this same reason we gratefully record their enduring contribution for posterity.2 It is with these words that Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803), theorist of Weimar Classicism and progenitor of Cultural Studies [Kulturwissenschaften], commences his critical review of Friedrich Schlichtegroll’s Nekrolog, an annual collection of biographies on the lives of exceptional people recently deceased. The review, part of Herder’s Briefe zu Beförderung der Humanität [Letters for the Advancement of Humanity] (1792-1797), outlines how the biographer’s task may be understood as an intrinsically political activity, particularly when it comes to collective rather than singular narratives, which were the dominant form of biographical discourse in eighteenth-century Germany.3 However, Herder’s incitation is aimed less at future biographers than at their readers. Instead of seeing obituaries as a passive act of mourning, he envisions a form of public memory that regards the lives of the departed as an inspiration for a better future: ‘They are not dead, our benefactors and friends: for their souls, their contributions to the human race, their memories live on.’4 Herder conceives of humanity [Humanität] as a communal pursuit, aimed at the development of the potential inherent in humankind. -

After Virtue: Once in Its Rank Orderingof the Virtues

http://www.jstor.org/stable/3561072 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=hastings. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Hastings Center is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Hastings Center Report. http://www.jstor.org F:ROM HOMER TO BENJAMIN FRANKLIN l The Nature of the Virtues by ALASDAIRMacINTYRE ourselves. For we would now seem to be saying that Ho- mer's concept of an arete, an excellence, is one thing and O ne responseto the historyof Greekand medieval that our concept of a virtue is quite anothersince a particu- thoughtabout the virtuesmight well be to suggest thateven lar qualitycan be an excellence in Homer's eyes, but not a within that relativelycoherent tradition of thoughtthere are virtue in ours and vice versa. -

Franklin and Mesmer

YALE JOURNAL OF BIOLOGY AND MEDICINE 66 (1993), pp. 325-331 Copyright C 1994. All rights reserved. Franklin and Mesmer: An Encountera Claude-Anne Lopezb Papers ofBenjamin Franklin, Yale University New Haven, Connecticut (Submitted May 27, 1993; sent for revision July 9; received and accepted July 26, 1993) In 1784, as the Enlightenment was on the wane, Paris faced a debate in which reason confronted the supematural and the mysterious. Dr. Mesmer, a graduate of the medical school in Vienna, had been running a "magnetic clinic" based on the belief that magnetic fluid, flowing from the stars, permeated all living beings and that every disease was due to an obstruction in the flow. By manipu- lating that fluid, he launched the concept of animal as opposed to mineral mag- netism and claimed to cure all ills. This got him into trouble with the medical faculty, and in 1778 he emigrated to Paris, creating secret societies all over France. Six years later, mesmerism was considered a threat, possibly deleter- ious to both mind and body. Louis XVI appointed two commissions to investi- gate this likely fraud. Dr. Guillotin headed one; the other, made up of five members of the Academy of Sciences, included an astronomer and was headed by Franklin, American Ambassador to France. Both commissions concluded that the success of mesmerism was due to the manipulation of the imagination. Mesmer protested vigorously but in vain. He left France and died in obscurity in 1815. In the year 1784, the population of Paris watched in mounting excitement as the two most celebrated foreigners in its midst confronted each other in a debate that involved medicine and humanism. -

Dalrev Vol82 Iss3 Authors.Pdf (175.3Kb)

CONTRIBUTORS M>.RTiiA F. BoWDEN teaches English at Kennesaw State University. She has edited a collection of three novels by Mary Davys for the University Press of Kentucky, and she is currently working on a study of the Church of England in the time of Laurence Sterne. RicK BoWERS teaches English at the University of Alberta. His recent work on early modern literature and drama appears in English Studies in Canada, Hunting/on Library Quarterly and 7be Set·enteenth Cen tury. MICHAEI. CHAPPEU teaches English at Western Connecticut State University. He has published on pohtJCs m !:ohelley and Milton, and 1S workmg on a book on the impact of Benjamin Franklin and Samuel Johnson on eighteenth-century western culture. He summers in Pt. Lorne, NS, where the bay is blue, the rocks are smooth, and the fish is fresh. CHARLOTrE M. CRAIG has written widely on topics of eighteenth-century Ger man and interdisciplinary literature. She served as General Editor of the series 7be Enlightenment.. German and Interdisciplinary Studies, and on the Board of Officers of the :"ortheast-Aroerican Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies. She currently teaches at Rutgers Univer sity. MICHAEL FODOR reaches French at DartmoU!h College. He works on the rela tionships between literature and economic life in eighteenth-century France. NANCY E. ]OHNSON teaches English at the State University of New York, New Paltz. She has published on the English jacobin novel, the Anti-Jacobin novel, and law and literarure in the 1790s. She has forthcoming Vol. 6 of 7be Court journals and Lerters of Frances Burney, 1 790-june 1791. -

Benjamin Franklin's Female and Male Pseudonyms: Sex, Gender, Culture, and Name Suppression from Boston to Philadelphia and Beyond

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Honors Projects History Department 2003 Benjamin Franklin's Female and Male Pseudonyms: Sex, Gender, Culture, and Name Suppression from Boston to Philadelphia and Beyond Jared C. Calaway '03 Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/history_honproj Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Calaway '03, Jared C., "Benjamin Franklin's Female and Male Pseudonyms: Sex, Gender, Culture, and Name Suppression from Boston to Philadelphia and Beyond" (2003). Honors Projects. 18. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/history_honproj/18 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. • Benjamin Franklin's Female and Male Pseudonyms Sex, Gender, Culture, and Name Suppression from Boston to Philadelphia and Beyond, 1722-1747 By Jared C. Calaway • "Historians relate, not so much what is done, as what they would have believed." -Richard Saunders [Benjamin Franklin], Poor Richard's Almanack, 1739 • Introduction Ever since Benjamin Franklin wrote his autobiography, biographers throughout the centuries have molded him into the model American. -

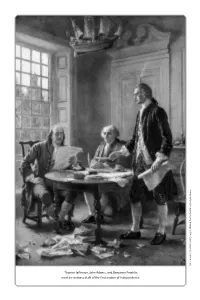

Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin Meet to Review a Draft of the Declaration of Independence

Writing the Declaration of independence. the Declaration Writing Jean Leon Gerome Ferris (1863–1930), Ferris Gerome Jean Leon Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Benjamin Franklin meet to review a draft of the Declaration of Independence. The Role of Lawyers in the American Revolution christopher a. cole Christopher A. Cole ([email protected]) is an attorney in Alpine, Utah. hrough the ages, prophets have foreseen and testified of the divine mission Tof America as the place for the Restoration of the gospel in the latter days. Beginning with the European Renaissance and the Age of Enlightenment, piece after piece of the Lord’s plan fell into place, ultimately leading to Joseph Smith’s First Vision in 1820. A review of colonial lawyers’ activities reveals their significant role in laying the groundwork for this long-awaited event. To the Prophet Joseph Smith, the Lord confirmed both the Revolutionary War and the founding of America as culminating preludes to the Restoration: “And for this purpose have I established the Constitution of this land, by the hands of wise men whom I raised up unto this very purpose, and redeemed the land by the shedding of blood” (D&C 101:80). President Joseph F. Smith put into perspective the import of this revela- tion to Joseph Smith. “This great American nation the Almighty raised up by the power of his omnipotent hand, that it might be possible in the latter days for the kingdom of God to be established on earth. If the Lord had not prepared the way by laying the foundations of this glorious nation, it would have been impossible (under the stringent laws and bigotry of the monarchial 47 48 Religious Educator · vol. -

John Locke and the Declaration of Independence

Cleveland State Law Review Volume 15 Issue 1 Mental Injury Damages Symposium Article 19 1966 John Locke and the Declaration of Independence Kenneth D. Stern Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clevstlrev Part of the Legal History Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Kenneth D. Stern, John Locke and the Declaration of Independence, 15 Clev.-Marshall L. Rev. 186 (1966) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cleveland State Law Review by an authorized editor of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. John Locke and the Declarationof Independence Kenneth D. Stern* 1 N AN ARTICLE published in the Journal of the American Bar Association in 1949, Dean Clarence Manion, then Dean of the College of Law of the University of Notre Dame, stated, "It is misleading to attribute the philosophy of the Declaration (of of John Locke." In support of his Independence) to the writings 2 contention, he quoted Locke's Second Treatise of Government, wherein Locke, in Section 95, states that once men enter into a community or government for the serving of their mutual interests, "the majority have the right to conclude the rest." Dean Manion feels that Locke thereby implies that the rights of minority groups and even of individuals are thus subordinated to the dictates of the majority. Dean Manion then quoted a letter written by Jefferson to Francis W. Gilmer on June 7, 1816, in which Jefferson said: Our legislators are not sufficiently apprised . -

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke A diligent study of Burke’s letters and manuscripts brings home the extent to which Burke’s approach to politics was a religious one. What is often spoken of as his “empiricism” appears in this light to be better described as Christian pessimism. As a Christian, Burke believed that the world is imperfect, he regarded his “enlightened” contemporaries’ faith in the perfectibility of man as atheistical as well as erroneous. Thus, whereas the fashionable intellectuals of his time looked for the progressive betterment of the world through the beneficial influence of Reason and Nature, Burke maintained that the moral order of the universe is unchanging. The first duty of rulers and legislators, he argued, is to the present, not to the future; their energies should be devoted to the correction of real ills, not to the promotion of an ideal order that exists only in the imagination. Burke put great faith in the inherited wisdom of tradition. He held that the moral order of the temporal world must necessarily include some evil, by reason of original sin. Men ought not to reject what is good in tradition merely because there is some admixture of evil in it. In man’s confused situation, advantages may often lie in balance and compromises between good and evil, even between one evil and another. It is an important part of wisdom to know how much evil should be tolerated. To search for too great a purity is only to produce fresh corruption. Burke was especially critical of revolutionary movements with noble humanitarian ends because he believed that people are simply not at liberty to destroy the state and its institutions in the hope of some contingent improvement. -

Geoffrey R. Stone

THE WORLD OF THE FRAMERS: A CHRISTIAN NATION? * Geoffrey R. Stone Each year, the UCLA School of Law hosts the Melville B. Nimmer Memorial Lecture. Since 1986, the lecture series has served as a forum for leading scholars in the fields of copyright and First Amendment law. In recent years, the lecture has been presented by distinguished scholars such as Lawrence Lessig, David Nimmer, Robert Post, Mark Rose, Kathleen Sullivan, and Jonathan Varat. The UCLA Law Review has published each of these lectures and proudly con- tinues that tradition by publishing an Essay by this year’s presenter, Professor Geoffrey R. Stone. Mel Nimmer was one of my heroes. Along with a handful of other giants of his generation, Mel helped transform our understanding of the First Amendment. Much of my own thinking about free speech builds on his insights. Most particularly, his explanation of categorical balancing as a central mode of First Amendment analysis both captured and redefined the evolution of free speech jurisprudence. Mel was also a brilliant First Amendment lawyer. My favorite story about him as a lawyer, which I have told to every First Amendment class I have taught over the past thirty-five years, and which I hope is familiar to many of you, involves the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in Cohen v. California.1 Forty years ago, at the height of the Vietnam War, Paul Robert Cohen was arrested for wearing a jacket bearing the words “Fuck the Draft” inside the Los Angeles courthouse.2 He was prosecuted and convicted for disturbing the peace.3 Mel Nimmer successfully represented Cohen before the Supreme Court, winning a landmark decision that Cohen’s message was protected by * Edward H. -

Commentary on the Death of Benjamin Franklin

MAKING THE REVOLUTION: AMERICA, 1763-1791 PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION On the DEATH of BENJAMIN FRANKLIN 17 April 1790 ca. 1746 (age: early forties) 1778 (age 72) ca. 1787 (early eighties) * Benjamin Franklin’s death on April 17, 1790, was the nation’s first loss of a Founding Father. In failing health and unremitting pain for several years, Franklin had given his last service to his country as a delegate to the 1787 Constitutional Convention. The Philadelphia printer, author of Poor Richard’s Almanac and countless satires and essays, signer of the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution, longtime representative to Britain and France, skillful negotiator of the peace treaty finalizing American independence, Franklin was buried in the Philadelphia Christ Church Burial Ground, next to his wife Deborah and near his son Folger who had died of smallpox as a child. Presented here are reports and tributes delivered in the two months after his death. What did they emphasize about Franklin as a man, a citizen, a pursuer of knowledge, and as a Founder of his country? Death of Benjamin Franklin, Philadelphia, 17 April 1790 The Federal Gazette, Philadelphia, 19 April 1790 Died on Saturday night, in the 85th year of his age, the illustrious BENJAMIN FRANKLIN. The world has been so long in possession of such extraordinary proofs of the singular abilities and virtues of this FRIEND OF MANKIND that it is impossible for a newspaper to increase his fame, or to convey his name to a part of the civilized globe where it is not already known and admired. -

Readings in Sade, Balzac and Proust. Douglas Brian Saylor Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1988 The urM der of the Father: Readings in Sade, Balzac and Proust. Douglas Brian Saylor Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Saylor, Douglas Brian, "The urM der of the Father: Readings in Sade, Balzac and Proust." (1988). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4538. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4538 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge.