One Hundred Years Ago (With Extracts from the Alpine Journal) C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution Géomorphologique Du Massif Des Ecrins-Pelvoux Depuis Le Dernier Maximum Glaciaire – Apports Des Nucléides Cosmogéniques Produits In-Situ Romain Delunel

Evolution géomorphologique du massif des Ecrins-Pelvoux depuis le Dernier Maximum Glaciaire – Apports des nucléides cosmogéniques produits in-situ Romain Delunel To cite this version: Romain Delunel. Evolution géomorphologique du massif des Ecrins-Pelvoux depuis le Dernier Maxi- mum Glaciaire – Apports des nucléides cosmogéniques produits in-situ. Géomorphologie. Université Joseph-Fourier - Grenoble I, 2010. Français. tel-00511048 HAL Id: tel-00511048 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00511048 Submitted on 23 Aug 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Ecole doctorale Terre Univers Environnement Laboratoire de Géodynamique des Chaînes Alpines THESE DE DOCTORAT DE L’UNIVERSITE DE GRENOBLE Evolution géomorphologique du massif des Ecrins- Pelvoux depuis le Dernier Maximum Glaciaire – Apports des nucléides cosmogéniques produits in-situ ROMAIN DELUNEL Soutenue publiquement le 24 juin 2010 devant le jury composé de : Friedhelm von Blanckenburg Rapporteur Yanni Gunnell Rapporteur Fritz Schlunegger Examinateur Philippe Schoeneich Examinateur -

For Alumni of the National Outdoor Leadership School

National Outdoor Leadership School NONpROfIT ORG. 284 Lincoln Street US POSTAGE Lander, WY 82520-2848 PAID www.nols.edu • (800) 710-NOLS pERmIT NO. 81 THE LEADER IN WILDERNESS EDUCATION jACkSON, WY 19 13 6 Research Partnership Research Country Their the NOLS World NOLS the University of Utah Utah of University Serve Grads NOLS Service Projects Around Around Projects Service For Alumni of the National Outdoor Leadership School Leadership Outdoor National the of Alumni For Leader THE No.3 24 Vol. 2009 Summer • • 2 THE Leader mEssagE from the dirEcTor summer months as passionate staff arrive and go to work in the mountains, in classrooms, in the issue room, or on rivers, ocean, or the telephones. In the May issue of Outside magazine, NOLS was recog- nized for the second year in a row as one of the top 30 companies to work for in the nation. Key to winning this honor is the dedication, passion, and commit- ment to service shared by our staff and volunteers. Throughout the year we also partner with other THE Leader NOLS Teton Valley students spend time doing trail work nonprofits to serve people and the environment. In during their course. an area of the Big Horn mountains. many cases these nonprofits direct students to us that would benefit from a NOLS education. Still others Joanne Kuntz ike most nonprofit organizations, service is fun- help provide scholarship support, which provides a Publications Manager Ldamental to the NOLS mission. In our case, NOLS education to a more diverse student base. Fi- we execute our mission in order to “serve people Rachel Harris nally, our alumni and donors provide essential sup- and the environment.” The NOLS community— Publications Intern port to further our goals and make it all happen. -

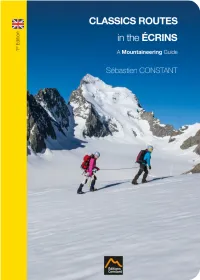

Preview Editions Seb Constant Classic Routes in the Ecrins

4 - INTRODUCTION - This guidebook cannot be considered a substitute for practical training. INTRODUCTION p. 2 II - DESCRIPTIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS p. 4 2-1 VALLOUISE p. 32 MAP OF THE SECTORS p. 5 - Access map p. 32 - Bans Valley p. 33 I - PRACTICAL INFORMATION - Sélé Valley p. 36 1-1 THE ÉCRINS MASSIF p. 6 - Glacier Noir Basin p. 48 - Access p. 6 - Glacier Blanc Basin p. 52 - Geography p. 7 2-2 HAUTE-ROMANCHE p. 76 1-2 A LONG HISTORY p. 8 - Access map p. 77 - Early exploration/In Coolidge’s footsteps p. 8 - Goléon Basin p. 78 - Recent changes and future trends p. 10 - Source of the Romanche p. 82 - Tabuchet Basin p. 90 1-3 MOUNTAIN HAZARDS p. 11 - Girose Basin p. 96 - Risk and the modern approach to safety p. 11 2-3 VÉNÉON p. 106 - A modern approach to safety p. 13 - Access map p. 107 - Selle Valley p. 108 1-4 DIFFICULTY RATINGS p. 14 - Soreiller Basin p. 114 - A complete reassessment p. 14 - Étançons Valley p. 122 - Technical difficulty p. 15 - Temple Écrins Basin p. 130 - Overall difficulty p. 15 - Pilatte Basin p. 134 - Lavey Valley p. 146 1-5 HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE p. 18 - Muzelle Valley p. 152 - Summit/altitude of the top of the route p. 18 - Route name / Route characteristics p. 18 2-4 VALJOUFFREY p. 154 - First ascent: climbers and date p. 19 - Access map p. 154 - Photos and page numbers p. 20 - Font Turbat Valley p. 156 - Approach / Route / Descent p. 20 2-5 VALGAUDEMAR p. -

One Hundred Years Ago C. A. Russell

88 Piz Bernilla, Ph Scerscell and Piz Roseg (Photo: Swiss atiollal TOl/rist Office) One hundred years ago (with extracts from the 'Alpine Journal') c. A. Russell The weather experienced in many parts of rhe Alps during rhe early months of 1877 was, to say the least, inhospitable. Long unsettled periods alternated with spells of extreme cold and biting winds; in the vicinity of St Morirz very low temperatures were recorded during January. One member of the Alpine Club able to make numerous high-level excur sions during the winter months in more agreeable conditions was D. W. Freshfield, who explored the Maritime Alps and foothills while staying at Cannes. Writing later in the AlpilJe Journal Freshfield recalled his _experiences in the coastal mountains, including an ascent above Grasse. 'A few steps to rhe right and I was on top of the Cheiron, under the lee of a big ruined signal, erected, no doubt, for trigonometrical purposes. It was late in the afternoon, and the sun was low in the western heavens. A wilder view I had never seen even from the greatest heights. The sky was already deepening to a red winter sunset. Clouds or mountains threw here and there dark shadows across earth and sea. "Far our at ea Corsica burst out of the black waves like an island in flames, reflecting the sunset from all its snows. From the sea-level only its mountain- 213 89 AiguiJle oire de Pelllerey (P!JOIO: C. Douglas Mill/er) 214 ONE HU DRED YEARS AGO topS, and these by aid of refraction, overcome the curvature of the globe. -

De La Meije Traversée

Sommets de légende TEXTE I CHRISTOPHE DUMAREST _ PHOTOS I MARC DAVIET POUR ALPES MAGAZINE TRAVERSÉE DELA CHEVAU LACHÉE FANTASTIQUE MEIJE Après le Cervin et la Dent du Géant*, le guide Christophe Dumarest nous convie à le suivre sur l’une des plus prestigieuses courses des Alpes, si ce n’est la plus belle. Longue et engagée, la traversée de la Meije hante les nuits de générations d’alpinistes. 60 * voir nos 146 et 147 d’Alpes magazine. Sommets de légende LA TRAVERSÉE DE LA MEIJE _ Les alpages qui s’étendent du plateau Instants de plénitude au sommet d’Emparis jusqu’aux aiguilles d’Arves du Doigt de Dieu (3 973 m), qui marque tranchent avec l’ambiance minérale plus véritablement la fin de notre traversée. Le Je reste bluffé par la qualité du rocher, au sud, dont la Meije est la porte d’entrée refuge de l’Aigle et le glacier du Tabuchet (ci-dessous). sont juste en dessous (page précédente). la diversité et l’ingéniosité du tracé. 63 Sommets de légende LA TRAVERSÉE DE LA MEIJE _ approche en direction de la Meije est progressive, la météo, semble contrarié par l’annonce qu’il va elle commence peu avant Vizille, là où la Romanche, nous faire. Ses grimaces ne présagent rien de bon. Il venue du glacier de la Plate des Agneaux, dans le sait, en tant que gardien, mais aussi comme guide nord du massif des Écrins, retrouve son confluent de haute montagne, ce que peut signifier le rêve le Drac. La route suit à contre-courant le torrent sur de la traversée de la Meije, toujours considérée près de 80 km à travers les vallées très encaissées comme l’une des, si ce n’est LA plus belle course L’que le cours d’eau a profondément creusées au des Alpes. -

Climbing in the Ecrins

DUNCAN TUNSTALL Climbing in the Ecrins he quantity and quality of high-standard rock climbs now available in T all areas of the Alps is astounding. Many of the areas are well known Chamonix, the Bregaglia, the Sella Pass area of the Dolomites, Sanetsch and, of course, Handeg. All offer routes of high quality and perfect rock. There is only one problem with these areas and that is that they are too popular. Fortunately, for those of us who value solitude in the mountains, there are still regions inthe Alps that provide routes of equal standing to the above but, for reasons not entirely understood, do not attract the crowds. One of the best kept secrets in British climbing circles is that some of the finest rock climbing in the Alps is now to be found in the Ecrins massif where many ofthe climbs stand comparison with anything that Chamonix or the Bregaglia have to offer. The quality of the rock is more than ade quate on most routes, although the odd slightly suspect pitch may add a spice of adventure. This factor has given the range an unfair reputation for looseness which, when combined with a lack of telepheriques, has been effective in keeping the crowds away. A brief summary follows of the best of the granite climbing in the Ecrins massif. But first I feel I ought to say something about the use of bolts. This is a difficult subject and many words have already been expended on it. My own views are simple: the high mountains, like our own small cliffs, are no place for bolts. -

Mountaineering Ventures

70fcvSs )UNTAINEERING Presented to the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO LIBRARY by the ONTARIO LEGISLATIVE LIBRARY 1980 v Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/mountaineeringveOObens 1 £1. =3 ^ '3 Kg V- * g-a 1 O o « IV* ^ MOUNTAINEERING VENTURES BY CLAUDE E. BENSON Ltd. LONDON : T. C. & E. C. JACK, 35 & 36 PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. AND EDINBURGH PREFATORY NOTE This book of Mountaineering Ventures is written primarily not for the man of the peaks, but for the man of the level pavement. Certain technicalities and commonplaces of the sport have therefore been explained not once, but once and again as they occur in the various chapters. The intent is that any reader who may elect to cull the chapters as he lists may not find himself unpleasantly confronted with unfamiliar phraseology whereof there is no elucidation save through the exasperating medium of a glossary or a cross-reference. It must be noted that the percentage of fatal accidents recorded in the following pages far exceeds the actual average in proportion to ascents made, which indeed can only be reckoned in many places of decimals. The explanation is that this volume treats not of regular routes, tariffed and catalogued, but of Ventures—an entirely different matter. Were it within his powers, the compiler would wish ade- quately to express his thanks to the many kind friends who have assisted him with loans of books, photographs, good advice, and, more than all, by encouraging countenance. Failing this, he must resort to the miserably insufficient re- source of cataloguing their names alphabetically. -

Mile High Mountaineer the Newsletter of the Denver Group of the Colorado Mountain Club

Mile High Mountaineer The newsletter of the Denver Group of the Colorado Mountain Club March 2013 www.hikingdenver.net Volume 45, No.3 www.cmc.org WHERE DID YOUR STATE MEMBERSHIP DUES GO IN 2012? Your Annual CMC Membership Dues consist of both State Dues and Group Dues. This graph, provided by former State Board President Alice White, illustrates howWhere the State Dues collected do are our used. State Membership Dues go? Membership Services, Accoun<ng, Web/IT, CEO, Marke<ng, Press Payroll and contract services 49% Development Membership Services 2% Insurance 98% Liability for Club and bldg, D&O for board and CEO 9% Building, Website, Admin, IT, and Deprecia<on Phones 18% Marke<ng Members, Outreach 7% Centennial Celebra<on Other 15% • Analysis based on FY 2012 Budget (including allocated costs). • Fundraising keeps individual dues down. Conserva@on and Educa@on rely heavily on fundraising in order to use limited funds from member dues. • Marke@ng is acquisi@on of new members, membership reten@on, outreach, and group marke@ng ECKART RODER EDUCATION FUND DINNER - MARCH 28 6:00 PM Social; 6:30 PM Potluck Dinner: The Eckart Roder Education Fund was many trips to the Grand Canyon, including 7:00 PM Presentations by 2012 AIARE established in 2003, in memory of Eckart rafting, hiking, and backpacking in this Level 1 Scholarship Recipients and a Roder who was a long-time member of the spectacular World Heritage Site. presentation of previous Grand Canyon Colorado Mountain Club. Eckart exemplified The Eckart Roder Education Fund Trips by Blake Clark & Rosemary Burbank the values of mountain safety, responsibility provides support for the educational $15 Tax Deductible Contribution to Eckhart and courtesy, which are the Fund’s priorities. -

Partie Nord-Est Du Massif Et Du Parc National Des Écrins

Date d'édition : 12/01/2021 https://inpn.mnhn.fr/zone/znieff/930012794 PARTIE NORD-EST DU MASSIF ET DU PARC NATIONAL DES ÉCRINS - MASSIF DU COMBEYNOT - MASSIF DE LA MEIJE ORIENTALE - GRANDE RUINE - MONTAGNE DES AGNEAUX - HAUTE VALLÉE DE LA ROMANCHE (Identifiant national : 930012794) (ZNIEFF Continentale de type 2) (Identifiant régional : 05104100) La citation de référence de cette fiche doit se faire comme suite : Jean-Charles VILLARET, Luc GARRAUD, Stéphane BELTRA, Alisson LECLERE, Jérémie VAN ES, Lionel QUELIN, Sonia RICHAUD, Géraldine KAPFER, .- 930012794, PARTIE NORD-EST DU MASSIF ET DU PARC NATIONAL DES ÉCRINS - MASSIF DU COMBEYNOT - MASSIF DE LA MEIJE ORIENTALE - GRANDE RUINE - MONTAGNE DES AGNEAUX - HAUTE VALLÉE DE LA ROMANCHE. - INPN, SPN-MNHN Paris, 29P. https://inpn.mnhn.fr/zone/znieff/930012794.pdf Région en charge de la zone : Provence-Alpes-Côte-d'Azur Rédacteur(s) :Jean-Charles VILLARET, Luc GARRAUD, Stéphane BELTRA, Alisson LECLERE, Jérémie VAN ES, Lionel QUELIN, Sonia RICHAUD, Géraldine KAPFER Centroïde calculé : 920486°-2004912° Dates de validation régionale et nationale Date de premier avis CSRPN : Date actuelle d'avis CSRPN : 28/09/2020 Date de première diffusion INPN : 01/01/1900 Date de dernière diffusion INPN : 05/01/2021 1. DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................................... 2 2. CRITERES D'INTERET DE LA ZONE ........................................................................................... 6 3. CRITERES DE DELIMITATION -

Travel & Exploration

catalogue twenty f ve EXPLORATION & TRAVEL Meridian Rare Books Tel: +44 (0) 208 694 2168 PO Box 51650 Mobile: +44 (0) 7912 409 821 London [email protected] SE8 4XW www.meridianrarebooks.co.uk United Kingdom VAT Reg. No.: GB 919 1146 28 Our books are collated in full and our descriptions aim to be accurate. We can provide further information and images of any item on request. If you wish to view an item from this catalogue, please contact us to make suitable arrangements. All prices are nett pounds sterling. VAT will be charged within the UK on the price of any item not in a binding. Postage is additional and will be charged at cost. Any book may be returned if unsatisfactory, in which case please advise us in advance. The present catalogue offers a selection of our stock. To receive a full listing of books in your area of interest, please enquire. ©Meridian Rare Books 2021 Cover illustration: Item 22 (detail) Travel and Exploration Catalogue 25 With an Index INDEX Africa 9, 10, 13, 19, 48, 49, 59, 71, 74-85, 87 Map 89, 90, 95, 96 Alps 2, 11, 15, 16, 18, 23, 28, 29, 37, 51, 54, 55, 57, 63, 100 Maritime 48, 91 Americas 4, 14, 20, 12, 30, 35, 39, 44, 54, 56, 62, 64, 72-85, 92 Middle East 32, 36, 53, 66, 89 Antarctic 40, 54, 67-70 Military 27, 58, 97, 98 Arctic 1, 3, 5-8, 20, 26, 47, 54, 65, 94 Missionary 74-87 Asia 10, 22, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 48, 50, 52, 60, 64, 80-5, 89, Mont Blanc 2, 11, 15, 18, 55, 63 90, 93, 97, 98 Mountaineering 2, 11, 15, 18, 21, 23, 28, 29, 34, 35, 37, 38, 41, Australasia 24, 34, 46, 48, 61, 77-85 42, -

En Oisans Mtb in Oisans

GUIDE PRATIQUE Oisans Tourisme VTT EN OISANS MTB IN OISANS BALADES ENDURO X COUNTRY LES STATIONS VTT 1 Bike-oisans.com Sommaire Un site internet dédié au vélo Contents en Oisans Le vélo de montagne en Oisans p.4 A website dedicated to biking Présentation du guide p.5 in Oisans Respect des sentiers et des utilisateurs p.6 Événements VTT en Oisans p.8 Encadrement VTT p.9 Location et réparation VTT p.10 Départ des itinéraires p.12 27 itinéraires p.14 > 69 Stations VTT de l’Oisans Les 2 Alpes p.70 Alpe d’Huez grand domaine VTT p.72 La Grave - La Meije - Villar d’Arène p.74 Mountain biking in Oisans p.4 RETROUVEZ TOUS LES A LIST OF ALL Introduction to the guide p.5 ÉVÈNEMENTS VTT THE MTB EVENTS Respecting the paths and other users p.6 ITINÉRAIRES ROUTES MTB events in Oisans p.8 Retrouvez tous les itinéraires Details of all these routes. MTB instructors and guides p.9 de ce guide. Print the road-book or down- Imprimez le road-book load the GPS tracks. MTB rental and repairs p.10 ou téléchargez le tracé sur votre Route start points p.12 GPS. 27 routes p.14 > 69 BIKE-OISANS.COM LES INFOS PRATIQUES PRACTICAL INFO MTB resorts in Oisans Toute l’info dont vous q Les infos pratiques q avez besoin pour MTB bike parks and areas Les 2 Alpes p.70 préparer votre séjour q Les domaines VTT q MTB rental and repairs Alpe d’Huez grand domaine VTT p.72 VTT en Oisans. -

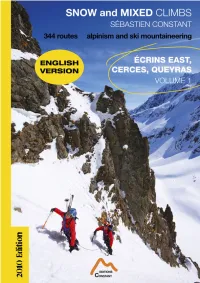

PDF Preview of Snow and Mixed Climbs Ecrins East

5 Valloire Albertville ECRINS EAST, CERCES, QUEYRAS, D902 ACCESS ROADS MAP N Grenoble Lyon Col du Galibier La Grave Col du Lautaret 5-CLAREE5-CLAREE Italy Villar Névache Fréjus & d'Arêne Mont-Blanc tunnels D994 4-GUISANE4-GUISANE Monêtier-les-Bains S24 D109 Col du 1 Montgenevre N94 Ailefroide Briançon Puy Chalvin Cervières 3-VALLOUISE3-VALLOUISE Villar Saint-Pancrace Vallouise D902 D4 D994E 6-BRIANCON6-BRIANCON Col de l'Isoard N94 2-FOURNEL2-FOURNEL D638 D947 L'Argentière-La-Bessée D5 Col Molines Agnel D902 Mont- VOLUME II Dauphin D60 Ceillac ECRINS WEST Guillestre 7-GUIL7-GUIL D638 Saint-Clément N94 St Marcellin 1-EMBRUN1-EMBRUN D39 D902 Embrun Crevoux N94 Col de Vars Gap Marseille VALLOUISE - Bans Valley - 31 LES BANS Glacier 0 km 0,5 km 1km des 21 Bans Névé Contreforts Scale Ovale des Bans N Brèche des Bans - 18 20 Pic des BV ANS alley Aupillous 17 Pas 15-16 Glacieracier du SellarSeSella Entraygues des Aupillous Bans hut 1624 m 14 2083 m Torrent des Bans Col du Sellar 12-13 GlacierGlacier de Pic Jocelme Bonvoisinn 8-9 10-11 Brèche de Bonvoisin Glacier des Bruyères Glacier de VALLOUISE Pic de Bonvoisin 5 - 7 l'Amirée VOLUME II Malamort WEST Crête de Aulp ValleyMartin Brèche des Bruyères Pic de Malamort Vallon des Bans Access to this valley is very long in winter conditions. The best way of reducing the walk in is to wait for good conditions in late autumn/early winter or in spring, when the road is open at least as far as the Chapelle de Béassac (1472 m), and sometimes as far as Entraygues (1625 m).