War Metaphors in Newspaper Coverage of the 2010 World Cup

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rugby World Cup Quiz

Rugby World Cup Quiz Round 1: Stats 1. The first eight World Cups were won by only four different nations. Which of the champions have only won it once? 2. Which team holds the record for the most points scored in a single match? 3. Bryan Habana and Jonah Lomu share the record for the most tries in the final stages of Rugby World Cup Tournaments. How many tries did they each score? 4. Which team holds the record for the most tries in a single match? 5. In 2011, Welsh youngster George North became the youngest try scorer during Wales vs Namibia. How old was he? 6. There have been eight Rugby World Cups so far, not including 2019. How many have New Zealand won? 7. In 2003, Australia beat Namibia and also broke the record for the largest margin of victory in a World Cup. What was the score? Round 2: History 8. In 1985, eight rugby nations met in Paris to discuss holding a global rugby competition. Which two countries voted against having a Rugby World Cup? 9. Which teams co-hosted the first ever Rugby World Cup in 1987? 10. What is the official name of the Rugby World Cup trophy? 11. In the 1995 England vs New Zealand semi-final, what 6ft 5in, 19 stone problem faced the English defence for the first time? 12. Which song was banned by the Australian Rugby Union for the 2003 World Cup, but ended up being sang rather loudly anyway? 13. In 2003, after South Africa defeated Samoa, the two teams did something which touched people’s hearts around the world. -

PROCEEDINGS of the 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION of the VETERANS of FOREIGN WARS of the UNITED STATES

116th Congress, 2d Session House Document 116–165 PROCEEDINGS of the 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES (SUMMARY OF MINUTES) Orlando, Florida ::: July 20 – 24, 2019 116th Congress, 2d Session – – – – – – – – – – – – – House Document 116–165 THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 120TH NATIONAL CON- VENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES COMMUNICATION FROM THE ADJUTANT GENERAL, THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES TRANSMITTING THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE 120TH NATIONAL CONVENTION OF THE VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES, HELD IN ORLANDO, FLORIDA: JULY 20–24, 2019, PURSUANT TO 44 U.S.C. 1332; (PUBLIC LAW 90–620 (AS AMENDED BY PUBLIC LAW 105–225, SEC. 3); (112 STAT. 1498) NOVEMBER 12, 2020.—Referred to the Committee on Veterans’ Affairs and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 40–535 WASHINGTON : 2020 U.S. CODE, TITLE 44, SECTION 1332 NATIONAL ENCAMPMENTS OF VETERANS’ ORGANIZATIONS; PROCEEDINGS PRINTED ANNUALLY FOR CONGRESS The proceedings of the national encampments of the United Spanish War Veterans, the Veterans of Foreign Wars of the United States, the American Legion, the Military Order of the Purple Heart, the Veterans of World War I of the United States, Incorporated, the Disabled American Veterans, and the AMVETS (American Veterans of World War II), respectively, shall be printed annually, with accompanying illustrations, as separate House documents of the session of the Congress to which they may be submitted. [Approved October 2, 1968.] ii LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL VETERANS OF FOREIGN WARS OF THE UNITED STATES KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI September, 2020 Honorable Nancy Pelosi The Speaker U. -

Fewer Hands, More Mercy: a Plea for a Better Federal Clemency System

FEWER HANDS, MORE MERCY: A PLEA FOR A BETTER FEDERAL CLEMENCY SYSTEM Mark Osler*† INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 465 I. A SWAMP OF UNNECESSARY PROCESS .................................................. 470 A. From Simplicity to Complexity ....................................................... 470 B. The Clemency System Today .......................................................... 477 1. The Basic Process ......................................................................... 477 a. The Pardon Attorney’s Staff ..................................................... 478 b. The Pardon Attorney ................................................................ 479 c. The Staff of the Deputy Attorney General ................................. 481 d. The Deputy Attorney General ................................................... 481 e. The White House Counsel Staff ................................................ 483 f. The White House Counsel ......................................................... 484 g. The President ............................................................................ 484 2. Clemency Project 2014 ................................................................ 485 C. The Effect of a Bias in Favor of Negative Decisions ...................... 489 II. BETTER EXAMPLES: STATE AND FEDERAL .......................................... 491 A. State Systems ................................................................................... 491 1. A Diversity -

2021 Major Sports Events Calendar Last Update: January 2021

2021 Major Sports Events Calendar Last update: January 2021 AMERICAN FOOTBALL Throughout 2021 National Football League - - Throughout 2021 NCAA Men's Football - - 7 Feb Super Bowl LV - TBC NFL International Series - - ATHLETICS Throughout 2021 IAAF Diamond League - - 5-7 Mar European Athletics Indoor Championship - - - 26 Sep Berlin Marathon 3 Oct London Marathon TBC 10 Oct Chicago Marathon TBC TBC 17 Oct Paris Marathon - 17 Oct Tokyo Marathon TBC 7 Nov New York Marathon TBC TBC Boston Marathon TBC TBC BASEBALL Throughout 2021 MLB regular season - - 20-30 Aug Little League World Series - - - October MLB World Series TBC BASKETBALL Throughout 2021 NBA regular season - Throughout 2021 NCAA Men's Basketball - - TBD NCAA Women’s Basketball Postseason - - 28-30 May EuroLeague Final Four - - May-July NBA Playoffs - COMBAT Throughout 2021 MMA and UFC Title Fights - Throughout 2021 Boxing World Title Fights - This calendar is for editorial planning purposes only and subject to change For a real-time calendar of coverage, visit reutersconnect.com/planning CRICKET Throughout 2021 Test matches - - Aug-Sep Test matches - England v India Throughout 2021 ODI matches - - TBC Throughout 2021 T20 matches - - - Oct-Nov ICC Men's T20 Cricket World Cup TBC CYCLING 8-30 May Giro D'Italia TBC 26 Jun - 18 Jul Tour de France 14 Aug - 5 Sep La Vuelta 19-26 Sep UCI Road Cycling World Championships - TBC TBC 13-17 Oct UCI Track Cycling World Championships - TBC TBC Throughout 2021 Top international races - ESPORTS Throughout 2021 Call of Duty League - - - Throughout 2021 DOTA 2 - - - TBC DOTA 2 - The International 10 TBC - - Throughout 2021 ESL One & IEM Tournaments TBC - - TBC FIFAe major competitions TBC - - Throughout 2021 League of Legends - - - TBC League of Legends World Championship TBC - - Throughout 2021 NBA2K League - - - Throughout 2021 Overwatch League - - - GOLF Throughout 2021 PGA TOUR Throughout 2021 European Tour - - - Throughout 2021 LPGA Tour TBC TBC - 8-11 April Masters - TBC 20-23 May PGA Championship - TBC 17-20 Jun U.S. -

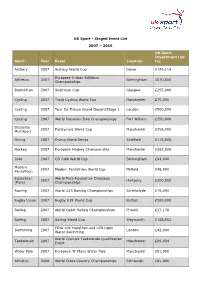

Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 Sport Year Event Location UK

UK Sport - Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 UK Sport Investment (up Sport Year Event Location to) Archery 2007 Archery World Cup Dover £199,114 European Indoor Athletics Athletics 2007 Birmingham £570,000 Championships Badminton 2007 Sudirman Cup Glasgow £255,000 Cycling 2007 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £75,000 Cycling 2007 Tour De France Grand Depart/Stage 1 London £500,000 Cycling 2007 World Mountain Bike Championships Fort William £250,000 Disability 2007 Paralympic World Cup Manchester £358,000 Multisport Diving 2007 Diving World Series Sheffield £115,000 Hockey 2007 European Hockey Championship Manchester £262,000 Judo 2007 GB Judo World Cup Birmingham £94,000 Modern 2007 Modern Pentathlon World Cup Milfield £48,000 Pentathlon Equestrian World Para-Equestrian Dressage 2007 Hartpury £200,000 (Para) Championships Rowing 2007 World U23 Rowing Championships Strathclyde £75,000 Rugby Union 2007 Rugby U19 World Cup Belfast £289,000 Sailing 2007 World Cadet Sailing Championships Phwelli £37,178 Sailing 2007 Sailing World Cup Weymouth £168,962 FINA 10K Marathon and LEN Open Swimming 2007 London £42,000 Water Swimming World Olympic Taekwondo Qualification Taekwondo 2007 Manchester £99,034 Event Water Polo 2007 European 'B' Mens Water Polo Manchester £81,000 Athletics 2008 World Cross Country Championships Edinburgh £81,000 Boxing 2008 European Boxing Championships Liverpool £181,038 Cycling 2008 World Track Cycling Championships Manchester £275,000 Cycling 2008 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £111,000 Disability 2008 Paralympic World -

Week 10 Game Release

WEEK 10 GAME RELEASE #BUFvsAZ Mark Dal ton - Senior Vice Presid ent, Med ia Rel ations Ch ris Mel vin - Director, Med ia Rel ations Mik e Hel m - Manag er, Med ia Rel ations Imani Sube r - Me dia Re latio ns Coordinato r C hase Russe ll - Me dia Re latio ns Coordinator BUFFALO BILLS (7-2) VS. ARIZONA CARDINALS (5-3) State Farm Stadium | November 15, 2020 | 2:05 PM THIS WEEK’S PREVIEW ARIZONA CARDINALS - 2020 SCHEDULE Arizona will wrap up a nearly month-long three-game homestand and open Regular Season the second half of the season when it hosts the Buffalo Bills at State Farm Sta- Date Opponent Loca on AZ Time dium this week. Sep. 13 @ San Francisco Levi's Stadium W, 24-20 Sep. 20 WASHINGTON State Farm Stadium W, 30-15 This week's matchup against the Bills (7-2) marks the fi rst of two games in a Sep. 27 DETROIT State Farm Stadium L, 23-26 five-day stretch against teams with a combined 13-4 record. Aer facing Buf- Oct. 4 @ Carolina Bank of America Stadium L 21-31 falo, Arizona plays at Seale (6-2) on Thursday Night Football in Week 11. Oct. 11 @ N.Y. Jets MetLife Stadium W, 30-10 Sunday's game marks just the 12th mee ng in a series that dates back to 1971. Oct. 19 @ Dallas+ AT&T Stadium W, 38-10 The two teams last met at Buffalo in Week 3 of the 2016 season. Arizona won Oct. 25 SEATTLE~ State Farm Stadium W, 37-34 (OT) three of the first four matchups between the teams but Buffalo holds a 7-4 - BYE- advantage in series aer having won six of the last seven games. -

A Comparative Analysis of the NFL's Disciplinary Structure: the Commissioner's Power and Players' Rights

Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 26 Volume XXVI Number 4 Volume XXVI Book 4 Article 5 2016 A Comparative Analysis of the NFL’s Disciplinary Structure: The Commissioner’s Power and Players’ Rights Cole Renicker Fordham University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Cole Renicker, A Comparative Analysis of the NFL’s Disciplinary Structure: The Commissioner’s Power and Players’ Rights, 26 Fordham Intell. Prop. Media & Ent. L.J. 1051 (2016). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/iplj/vol26/iss4/5 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Intellectual Property, Media and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Comparative Analysis of the NFL’s Disciplinary Structure: The Commissioner’s Power and Players’ Rights Cover Page Footnote Notes and Articles Editor, Fordham Intellectual Property, Media & Entertainment Law Journal, Volume XXVII; J.D. Candidate, Fordham University School of Law, 2017; B.S., Business Management, Pennsylvania State University, 2014. I would like to first thank Professor James Brudney for all of his constructive feedback and his involvement throughout the writing process. I would like to thank the IPLJ XXVI Editorial Board, and Staff, especially Patrick O’Keefe, Kathryn Rosenberg, and Elizabeth Walker, for their constant guidance and accessibility whenever I had any questions or concerns. -

Nfl) Retirement System

S. HRG. 110–1177 OVERSIGHT OF THE NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE (NFL) RETIREMENT SYSTEM HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION SEPTEMBER 18, 2007 Printed for the use of the Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 76–327 PDF WASHINGTON : 2012 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:26 Oct 23, 2012 Jkt 075679 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 S:\GPO\DOCS\76327.TXT JACKIE SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMMERCE, SCIENCE, AND TRANSPORTATION ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION DANIEL K. INOUYE, Hawaii, Chairman JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER IV, West Virginia TED STEVENS, Alaska, Vice Chairman JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona BYRON L. DORGAN, North Dakota TRENT LOTT, Mississippi BARBARA BOXER, California KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas BILL NELSON, Florida OLYMPIA J. SNOWE, Maine MARIA CANTWELL, Washington GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon FRANK R. LAUTENBERG, New Jersey JOHN ENSIGN, Nevada MARK PRYOR, Arkansas JOHN E. SUNUNU, New Hampshire THOMAS R. CARPER, Delaware JIM DEMINT, South Carolina CLAIRE MCCASKILL, Missouri DAVID VITTER, Louisiana AMY KLOBUCHAR, Minnesota JOHN THUNE, South Dakota MARGARET L. CUMMISKY, Democratic Staff Director and Chief Counsel LILA HARPER HELMS, Democratic Deputy Staff Director and Policy Director CHRISTINE D. KURTH, Republican Staff Director and General Counsel PAUL NAGLE, Republican Chief Counsel (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:26 Oct 23, 2012 Jkt 075679 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\GPO\DOCS\76327.TXT JACKIE C O N T E N T S Page Hearing held on September 18, 2007 .................................................................... -

Jay-Z, Roger, and Kaepernick

University of Central Florida STARS On Sport and Society Public History 8-20-2019 Jay-Z, Roger, and Kaepernick Richard C. Crepeau University of Central Florida, [email protected] Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Other History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/onsportandsociety University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Commentary is brought to you for free and open access by the Public History at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in On Sport and Society by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recommended Citation Crepeau, Richard C., "Jay-Z, Roger, and Kaepernick" (2019). On Sport and Society. 841. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/onsportandsociety/841 SPORT AND SOCIETY FOR H-ARETE – JAY-Z, ROGER, AND KAEPERNICK AUGUST 20, 2019 The National Football League is about to begin its 100th season of play. This will be celebrated ad nauseam and the 2020-2021 season will be celebrated as the 100th Anniversary season of the NFL. The marketing folks at the NFL no doubt spend weeks and months figuring out how to milk this milestone for as long as possible. This points to the self-evident proposition that the National Football League is all about marketing and only incidentally about actual football. One obstacle in the NFL marketing orbit is the persistent set of issues surrounding Colin Kaepernick and the National Anthem protests. Three years ago, and it seems much longer, the San Francisco Forty-Niner’s quarterback went down on one knee during the playing of the anthem during an exhibition game in San Diego. -

No 57 October 1988 AD ASTRA PER ASPERA

THE rCOLFOAlSf f I folk «r 1 No 57 October 1988 AD ASTRA PER ASPERA October 1988 COLFEIAN the Chronicles of Colfe's School and of the Old Colfeians' Association The Master, Richard Scriven, planting a tree on the occasion of the Leathersellers' cricket match, 26th June, 1988 following the opening of the new Preparatory School on 23rd June. Mr Scriven's father laid the Foundation Stone for the Main School Building in 1964. ISSN 0010-0670 COVER DESIGN With a change in the format of the Colfeian, it was felt appropriate to change also the design of the cover.'The design chosen for this year at least, emphasises continuity. It is the design used on every issue from vol.1 no.l in December 1900 until vol.17 no. 67 in December 1939. In those days the Colfeian was the magazine of the Old Colfeians, while from 1902 the school had its own magazine, Colfensia. In 1951 the two magazines combined, thus beginning the present sequence of the Colfeian. The original cover, now being re-used, was designed by Charles J. Folkard whose signature it bears. More on this eminent Old Colfeian appears on another page. For his design, Folkard drew the heraldic stone which hung over the entrance to Colfe's Almshouses in Lewisham, depicting the arms of Abraham Colfe and the Leathersellers' Company. As a result of the school's celebration of Folkard this year, which accompanied the acquisition of some of his original drawings, the stone itself has been re-discovered. Since the demolition of the almshouses, it has lain, albeit somewhat damaged and begrimed in the vaults of Manor House, Lee. -

Scope and Authority of Sports League Commissioner Disciplinary Power: Bounty and Beyond

Scope and Authority of Sports League Commissioner Disciplinary Power: Bounty and Beyond Adriano Pacifici I. Introduction ................................................................................................... 93 II. Creation and Evolution of today’s “Commissioner” .................................... 95 III. Power of Commissioners’ Review Under Each League’s Current CBA, Constitution, and By-Laws .......................................................... 99 A. Major League Baseball ................................................................... 100 B. National Hockey League ................................................................ 101 C. National Basketball League ............................................................ 102 D. National Football League ............................................................... 103 IV. NFL’s Disciplinary Review Issues through the lens of the “BountyGate” Scandal ......................................................................... 105 A. Background ..................................................................................... 105 B. Commissioner Goodell’s Initial Decision, & Decision on Appeal .......................................................................................... 106 C. NFLPA Files Lawsuit ..................................................................... 107 D. Evident Partiality ............................................................................ 108 E. Tagliabue Decision ........................................................................ -

UK Sport - Staged Event List

UK Sport - Staged Event List 2007 – 2019 UK Sport Investment (up Sport Year Event Location to) Archery 2007 Archery World Cup Dover £199,114 European Indoor Athletics Athletics 2007 Birmingham £570,000 Championships Badminton 2007 Sudirman Cup Glasgow £255,000 Cycling 2007 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £75,000 Cycling 2007 Tour De France Grand Depart/Stage 1 London £500,000 Cycling 2007 World Mountain Bike Championships Fort William £250,000 Disability 2007 Paralympic World Cup Manchester £358,000 Multisport Diving 2007 Diving World Series Sheffield £115,000 Hockey 2007 European Hockey Championship Manchester £262,000 Judo 2007 GB Judo World Cup Birmingham £94,000 Modern 2007 Modern Pentathlon World Cup Milfield £48,000 Pentathlon Equestrian World Para-Equestrian Dressage 2007 Hartpury £200,000 (Para) Championships Rowing 2007 World U23 Rowing Championships Strathclyde £75,000 Rugby Union 2007 Rugby U19 World Cup Belfast £289,000 Sailing 2007 World Cadet Sailing Championships Phwelli £37,178 Sailing 2007 Sailing World Cup Weymouth £168,962 FINA 10K Marathon and LEN Open Swimming 2007 London £42,000 Water Swimming World Olympic Taekwondo Qualification Taekwondo 2007 Manchester £99,034 Event Water Polo 2007 European 'B' Mens Water Polo Manchester £81,000 Athletics 2008 World Cross Country Championships Edinburgh £81,000 Boxing 2008 European Boxing Championships Liverpool £181,038 Cycling 2008 World Track Cycling Championships Manchester £275,000 Cycling 2008 Track Cycling World Cup Manchester £111,000 Disability 2008 Paralympic World