History & Humanities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH

UGP COVER 2012 22/3/11 14:01 Page 2 THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH Undergraduate Prospectus Undergraduate 2012 Entry 2012 THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH Undergraduate Prospectus 2012 Entry www.ed.ac.uk EDINB E56 UGP COVER 2012 22/3/11 14:01 Page 3 UGP 2012 FRONT 22/3/11 14:03 Page 1 UGP 2012 FRONT 22/3/11 14:03 Page 2 THE UNIVERSITY of EDINBURGH Welcome to the University of Edinburgh We’ve been influencing the world since 1583. We can help influence your future. Follow us on www.twitter.com/UniofEdinburgh or watch us on www.youtube.com/user/EdinburghUniversity UGP 2012 FRONT 22/3/11 14:03 Page 3 The University of Edinburgh Undergraduate Prospectus 2012 Entry Welcome www.ed.ac.uk 3 Welcome Welcome Contents Contents Why choose the University of Edinburgh?..... 4 Humanities & Our story.....................................................................5 An education for life....................................................6 Social Science Edinburgh College of Art.............................................8 pages 36–127 Learning resources...................................................... 9 Supporting you..........................................................10 Social life...................................................................12 Medicine & A city for adventure.................................................. 14 Veterinary Medicine Active life.................................................................. 16 Accommodation....................................................... 20 pages 128–143 Visiting the University............................................... -

Osteomyelitis : an Historical Survey

GLASGOW MEDICAL JOURNAL Vol,. 32 (Vol. 150 Old Series). MAY 1951 No. 5 The Journal of The Royal Memco-Chikuugical Society of Glasgow OSTEOMYELITIS : AN HISTORICAL SURVEY. WALLACE M. DENNISON, M.B., Ch.B., F.R.C.S.(Ed.). from the Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Glasgow. II c stand upon the intellectual shoulders of the medical giants of bygone days and, because of the help they afford us, we are able to see more clearly than they were able to do. ?Claude Bernard (1813-78). Pyogenic infection of bone is as old as man. We do not know all the diseases to which the flesh of palaeolithic man was heir, but his surviving bones tell us that a common disease was inflammation of the bone involving a joint and producing deformity. The first written record of knowledge of bone disease comes to us in the Smith Surgical Papyrus written about 1600 B.C. (Breasted, 1930). -I he Egyptians could not eliminate magic from their medicine and ibis- headed Thos, hawk-headed Horus, lion-headed Sekhmet, and other such ??ds, overwhelmed the laws of science. The papyrus tells us that bone Caries and suppuration were treated by poultices of ground snakes, frogs and puppies and by decoctions of various herbs. Evidence of osteo- myelitis has been found in some of the earliest Egyptian mummies. In aiicient China, inflammation was treated by the application of small Pieces of slow-burning wood over the painful area, while the Hindus had an old dogma?' The fire cures diseases which cannot be cured by the knife and drugs.' The Hindus were skilled surgeons and they immobilized lnfiamed and broken limbs by light wooden splints. -

Edicai Uvuali

THE I + edicaI+. UVUaLI THE JOURNAL OF THE BRITISH MEDICAL ASSOCIATION. EDITED BY NORMAN GERALD HORNER, M.A., M.D. VOLUTME I, 1931. JANUARY TO JUNE. XtmEan 0n PRINTED AND PUBLISHED AT THE OFFICE OF THE BRITISH MEDICAL ASSOCIATION, TAVISTOCK SQUARE, LONDON, W.C.1. i -i r TEx BsxTzSu N.-JUNE, 19311 I MEDICAL JOUUNAI. rI KEY TO DATES AND PAGES. THE following table, giving a key to the dates of issue andI the page numbers of the BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL and SUPPLEMENT in the first volume for 1931, may prove convenient to readers in search of a reference. Serial Date of Journal Supplement No. Issue. Pages. Pages. 3652 Jan. 3rd 1- 42 1- 8 3653 10th 43- 80 9- 12 3654 it,, 17th 81- 124 13- 16 3655 24th 125- 164 17- 24 3656 31st 165- 206 25- 32 3657 Feb. 7th 207- 252 33- 44 3658 ,, 14th 253- 294 45- 52 3659 21st 295- 336 53- 60 3660 28th 337- 382 61- 68 3661 March 7th 383- 432 69- 76 3662 ,, 14th 433- 480 77- 84 3663 21st 481- 524 85- 96 3664 28th 525- 568 97 - 104 3665 April 4th 569- 610 .105- 108 3666 11th 611- 652 .109 - 116 3667 18th 653- G92 .117 - 128 3668 25th 693- 734 .129- 160 3669 May 2nd 735- 780 .161- 188 3670 9th 781- 832 3671 ,, 16th 833- 878 .189- 196 3672 ,, 23rd 879- 920 .197 - 208 3673 30th 921- 962 .209 - 216 3674 June 6th 963- 1008 .217 - 232 3675 , 13th 1009- 1056 .233- 244 3676 ,, 20th 1057 - 1100 .245 - 260 3677 ,, 27th 1101 - 1146 .261 - 276 INDEX TO VOLUME I FOR 1931 READERS in search of a particular subject will find it useful to bear in mind that the references are in several cases distributed under two or more separate -

126613742.23.Pdf

c,cV PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY THIRD SERIES VOLUME XXV WARRENDER LETTERS 1935 from, ike, jxicUtre, in, ike, City. Chcomkers. Sdinburyk, WARRENDER LETTERS CORRESPONDENCE OF SIR GEORGE WARRENDER BT. LORD PROVOST OF EDINBURGH, AND MEMBER OF PARLIAMENT FOR THE CITY, WITH RELATIVE PAPERS 1715 Transcribed by MARGUERITE WOOD PH.D., KEEPER OF THE BURGH RECORDS OF EDINBURGH Edited with an Introduction and Notes by WILLIAM KIRK DICKSON LL.D., ADVOCATE EDINBURGH Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable Ltd. for the Scottish History Society 1935 Printed in Great Britain PREFACE The Letters printed in this volume are preserved in the archives of the City of Edinburgh. Most of them are either written by or addressed to Sir George Warrender, who was Lord Provost of Edinburgh from 1713 to 1715, and who in 1715 became Member of Parliament for the City. They are all either originals or contemporary copies. They were tied up in a bundle marked ‘ Letters relating to the Rebellion of 1715,’ and they all fall within that year. The most important subject with which they deal is the Jacobite Rising, but they also give us many side- lights on Edinburgh affairs, national politics, and the personages of the time. The Letters have been transcribed by Miss Marguerite Wood, Keeper of the Burgh Records, who recognised their exceptional interest. Miss Wood has placed her transcript at the disposal of the Scottish History Society. The Letters are now printed by permission of the Magistrates and Council, who have also granted permission to reproduce as a frontispiece to the volume the portrait of Sir George Warrender which in 1930 was presented to the City by his descendant, Sir Victor Warrender, Bt., M.P. -

Matthew Baillie Gairdner, the Royal Medical Society and the Problem of the Second Heart Sound

HISTORY MATTHEW BAILLIE GAIRDNER, THE ROYAL MEDICAL SOCIETY AND THE PROBLEM OF THE SECOND HEART SOUND M. Nicolson, Senior Lecturer, Centre for the History of Medicine, University of Glasgow, and J. Windram, Senior House Officer, Cardiology Department, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh SUMMARY In 1830, Matthew Baillie Gairdner (1808–88) was the first to propose that the second heart sound was produced by the closure of the semilunar valves. He proposed this theory, while a student at Edinburgh University, in an oral presentation to the Royal Medical Society (RMS). Gairdner (Figure 1) has been largely ignored by both nineteenth and twentieth century historians of cardiology. This paper presents an account of his life, his discovery and the scientific controversy to which he contributed, and argues that an appreciation of his work and that of his student colleagues should cause us to re-evaluate the significance of the RMS as a research forum in the early nineteenth century. FIGURE 1 Suggestions are made as to why his contribution to our Matthew Baillie Gairdner. From: A. Porteus; The History of Crieff understanding of the heart sounds has been neglected. from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson and Ferrier; 1912. Reproduced with the kind INTRODUCTION permission of the Trustees of the National Library of Scotland. The Harveian Discourse for 1887 was delivered by Dr George W. Balfour, Consulting Physician to the Royal The character of Matthew Baillie Gairdner’s work and Infirmary of Edinburgh and a former President of the career is intriguing for several reasons. How did an Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.1 He outlined Edinburgh medical student manage to make a discovery the long debate which had taken place, from Laennec’s of such significance? Why has his contribution to the time to his own, regarding the nature and origin of the study of the heart been largely forgotten? And why did sounds of the heart. -

28415 NDR Credits

28415 NDR Credits Billing Primary Liable party name Full Property Address Primary Liable Party Contact Add Outstanding Debt Period British Airways Plc - (5), Edinburgh Airport, Edinburgh, EH12 9DN Cbre Ltd, Henrietta House, Henrietta Place, London, W1G 0NB 2019 -5,292.00 Building 320, (54), Edinburgh Airport, Edinburgh, Building 319, World Cargo Centre, Manchester Airport, Manchester, Alpha Lsg Ltd 2017 -18,696.00 EH12 9DN M90 5EX Building 320, (54), Edinburgh Airport, Edinburgh, Building 319, World Cargo Centre, Manchester Airport, Manchester, Alpha Lsg Ltd 2018 -19,228.00 EH12 9DN M90 5EX Building 320, (54), Edinburgh Airport, Edinburgh, Building 319, World Cargo Centre, Manchester Airport, Manchester, Alpha Lsg Ltd 2019 -19,608.00 EH12 9DN M90 5EX The Maitland Social Club Per The 70a, Main Street, Kirkliston, EH29 9AB 70 Main Street, Kirkliston, West Lothian, EH29 9AB 2003 -9.00 Secretary/Treasurer 30, Old Liston Road, Newbridge, Midlothian, EH28 The Royal Bank Of Scotland Plc C/O Gva , Po Box 6079, Wolverhampton, WV1 9RA 2019 -519.00 8SS 194a, Lanark Road West, Currie, Midlothian, Martin Bone Associates Ltd (194a) Lanark Road West, Currie, Midlothian, EH14 5NX 2003 -25.20 EH14 5NX C/O Cbre - Corporate Outsourcing, 55 Temple Row, Birmingham, Lloyds Banking Group 564, Queensferry Road, Edinburgh, EH4 6AT 2019 -2,721.60 B2 5LS Unit 3, 38c, West Shore Road, Edinburgh, EH5 House Of Fraser (Stores) Ltd Granite House, 31 Stockwell Street, Glasgow, G1 4RZ 2008 -354.00 1QD Tsb Bank Plc 210, Boswall Parkway, Edinburgh, EH5 2LX C/O Cbre, 55 Temple -

Special Articles

Walmsley Crichton-Browne’s biological psychiatry special articles Psychiatric Bulletin (2003), 27,20^22 T. WAL M S L E Y Crichton-Browne’s biological psychiatry Sir James Crichton-Browne (1840^1938) held a uniquely the brothers at the centre of British phrenology in distinguished position in the British psychiatry of his Edinburgh in the 1820s. time. Unburdened by false modesty, he called himself The central proposition of phrenology ^ that ‘the doyen of British medical psychology’ and, in the the brain is the organ of the mind ^ seems entirely narrow sense, he was indeed its most senior practitioner. unremarkable today. In the 1820s, however, it was a At the time of his death, he could reflect on almost half provocative notion with worrying implications for devout a century’s service as Lord Chancellor’s Visitor and a religious people. In Edinburgh, George Combe attached similar span as a Fellow of the Royal Society. great importance to drawing the medical profession into Yet,today,ifheisrememberedatall,itisasanearly an alliance and he pursued this goal with determination proponent of evolutionary concepts of mental disorder and occasional spectacular setbacks. (Crow, 1995). Summarising his decade of research at In 1825, Andrew Combe advanced phrenological the West Riding Asylum in the 1870s, Crichton-Browne ideas in debate at the Royal Medical Society and the proposed that in the insane the weight of the brain furore which followed resulted in the Society issuing writs was reduced, the lateral ventricles were enlarged and the prohibiting the phrenologists from publishing the burden of damage fell on the left cerebral hemisphere in proceedings. -

Former Fellows Biographical Index Part

Former Fellows of The Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783 – 2002 Biographical Index Part Two ISBN 0 902198 84 X Published July 2006 © The Royal Society of Edinburgh 22-26 George Street, Edinburgh, EH2 2PQ BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF FORMER FELLOWS OF THE ROYAL SOCIETY OF EDINBURGH 1783 – 2002 PART II K-Z C D Waterston and A Macmillan Shearer This is a print-out of the biographical index of over 4000 former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh as held on the Society’s computer system in October 2005. It lists former Fellows from the foundation of the Society in 1783 to October 2002. Most are deceased Fellows up to and including the list given in the RSE Directory 2003 (Session 2002-3) but some former Fellows who left the Society by resignation or were removed from the roll are still living. HISTORY OF THE PROJECT Information on the Fellowship has been kept by the Society in many ways – unpublished sources include Council and Committee Minutes, Card Indices, and correspondence; published sources such as Transactions, Proceedings, Year Books, Billets, Candidates Lists, etc. All have been examined by the compilers, who have found the Minutes, particularly Committee Minutes, to be of variable quality, and it is to be regretted that the Society’s holdings of published billets and candidates lists are incomplete. The late Professor Neil Campbell prepared from these sources a loose-leaf list of some 1500 Ordinary Fellows elected during the Society’s first hundred years. He listed name and forenames, title where applicable and national honours, profession or discipline, position held, some information on membership of the other societies, dates of birth, election to the Society and death or resignation from the Society and reference to a printed biography. -

Scotland's New Year Festival

SCOTLAND’S NEW YEAR FESTIVAL FOREWORD A very warm welcome to you in our third year of producing Edinburgh’s Hogmanay, as we invite you to BE TOGETHER this Hogmanay. Now more than ever is the time to celebrate ‘togetherness’ and what better way than surrounded by people from all over the world at New Year? From performers to audiences, this festival is about coming together, being together, sharing experiences together and sharing the start of a new year arm in arm and side by side. BE ready to party from the 30th December as we return with a programme of events at the magnificent McEwan Hall. From the return of hit clubbing experience Symphonic Ibiza on 30th December featuring Ibiza DJs and a live orchestra, to the first party in 2020 celebrating the new year along with the Southern Hemisphere at G’Day 2020 with Kylie Auldist on 31 December. Jazz legends Ronnie Scott’s Big Band will play a gala concert on 31st December to give an alternative lead up to the bells and renowned DJ Judge Jules will spin into the wee small hours at our first ever Official After-Party. BE a trailblazer at the Torchlight Procession in partnership with VisitScotland. The historic event culminates in Holyrood Park as torchbearers create a symbol to share with the world: this year two figures holding hands - both residents and visitors to Scotland opening their door to the world and saying BE together. BE in the thick of it at the world famous Street Party hosted by Johnnie Walker, with a brilliantly eclectic programme of music, street theatre and spectacle. -

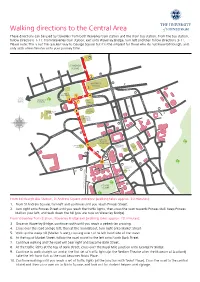

Walking Directions to the Central Area These Directions Can Be Used by Travellers from Both Waverley Train Station and the Main Bus Station

Walking directions to the Central Area These directions can be used by travellers from both Waverley train station and the main bus station. From the bus station, follow directions 1-11. From Waverley train station, exit onto Waverley Bridge, turn left and then follow directions 3-11. Please note: This is not the quickest way to George Square but it is the simplest for those who do not know Edinburgh, and only adds a few minutes onto your journey time. 1 ST ANDREW T S SQUARE H T I E L HANOVER ST 2 FREDERICK ST PRINCES ST GEORGE ST W A V WAVERLEY NORTH BRIDGE E P R L STATION E Y 3 B R JEFFREY ST PRINCES ST I D G ART E GALLERIES 5 4 COCKBURN ST TO THE N ST MARY’S ST ST JOHN ST O CANONGATE WESTERN 6 MARKET ST PRINCES ST RT CITY GENERAL GARDENS H BAN 7 K ST BANK ST CHAMBERS P HIGH ST (ROYAL MILE) 8 ST GILES EDINBURGH CATHEDRAL HOLYROOD ROAD CASTLE SOUTH BRIDGE P NATIONAL LIBRARY OF GEORGE IV BRIDGE T SCOTLAND S N A I R COWGATE P O T T S L E C Y I R A A V M FIR S IN A N C CANDLEMAKER ROW E T ST GRASSMARKET RS S ND MBE MO HA RUM C NATIONAL D MUSEUM OF SCOTLAND R GREYFRIARS 9 PEDESTRIAN SURGEON’S IC P UNDERPASS H KIRK O HALL M NICOLSON ST T FESTIVAL O WEST PORT T T THEATRE N S E D FORREST ROAD FORREST R N B P A R R I L I O S H A T T W HILL PLACE C LADY LAWSON STREET O O E PL L E RICHMOND LANE AC PL 10 BRISTO IOT TEV SQUARE EDINBURGH MIDDLE MEADOW WALK CENTRAL LAURISTON PLACE MOSQUE P D A V I E S CRICHTON ST W. -

Lesions at the Foramen of Monro Causing Obstructive Hydrocephalus Ashish Chugh, Sarang Gotecha, Prashant Punia and Neelesh Kanaskar

Chapter Lesions at the Foramen of Monro Causing Obstructive Hydrocephalus Ashish Chugh, Sarang Gotecha, Prashant Punia and Neelesh Kanaskar Abstract The foramen of Monro has also been referred to by the name of interventricular foramen. The structures comprising this foramen are the anterior part of the thala- mus, the fornix and the choroid plexus. Vital structures surround the foramen, the damage to which can be catastrophic leading to disability either temporary or permanent. In the literature it has been shown that tumors occurring in the area of interventricular foramen are rare and usually cause hydrocephalus. The operative approach depends upon the location of the tumor which can be either in the lateral or the third ventricle. Various pathologies which can lead to foramen of Monro obstruction and obstructive hydrocephalus include colloid cyst, craniopharyngioma, subependymal giant cell astrocytoma [SEGA], Neurocysti- cercosis, tuberculous meningitis, pituitary macroadenoma, neurocytoma, ventriculitis, multiseptate hydrocephalus, intraventricular hemorrhage, function- ally isolated ventricles, choroid plexus tumors, subependymomas and idiopathic foramen of monro stenosis. In this chapter, we will discuss the various lesions at the level of foramen of Monro causing obstructive hydrocephalus and the management and associated complications of these lesions based on their type, clinical picture and their appearance on imaging. Keywords: Foramen of Monro, interventricular foramen, obstruction, obstructive hydrocephalus, raised intracranial pressure 1. Introduction The foramen of Monro has also been referred to by the name of interventricular foramen. The first description of this foramen was given by Alexander Monro in the year 1783 and 1797. The authors of that era were of the opinion that the use of nomenclature ‘foramen of monro’ was incorrect; instead ‘interventricular foramen’ would be more apt. -

'A Chief Standard Work': the Rise and Fall of David Hume's' History of England'. 1754-C. 1900

’A CHIEF STANDARD WORK’: THE RISE AND FALL OF DAVID HUME’S HISTORY OF ENGLAND. 1754-C.1900. UNIVERSITY OF LONDON PhD THESIS JAMES ANDREW GEORGE BAVERSTOCK UNIVERSITY COLLEGE [LONOIK. ProQuest Number: 10018558 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10018558 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract. This thesis examines the influence of David Hume’s History of England during the century of its greatest popularity. It explores how far the long-term fortunes of Hume’s text matched his original aims for the work. Hume’s success in creating a classic popular narrative is demonstrated, but is contrasted with the History's failure to promote the polite ’coalition of parties’ he wished for. Whilst showing that Hume’s popularity contributed to tempering some of the teleological excesses of the ’whig version’ of English history, it is stressed that his work signally failed in dampening ’Whig’/ ’Tory’ conflict. Rather than provide a new frame of reference for British politics, as Hume had intended, the History was absorbed into national political culture as a ’Tory’ text - with important consequences for Hume’s general reputation as a thinker.