The System of Divine Service Quotations in the Life of Stephen of Perm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Orthodox Liturgical Year and Its Theological Structure

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 8 Original Research The orthodox liturgical year and its theological structure Author: The concept of ‘liturgical year’ indicates a reference to the meaning of the measuring units 1,2 Dan A. Streza of civil time, and especially to the cosmic entities that determine the general rhythm of Affiliations: time – the sun and the moon. Interestingly, the liturgical time depends both on the structure 1Department of Orthodox of civil time, and, on the two discrete systems of the solar and lunar cycles, which have Theology, Faculty of Orthodox always been underpinnings of time measuring. The special importance and influence that Theology, Lucian Blaga the cosmical rhythms exert on the entire human life are also felt in the structure and theology University of Sibiu, Sibiu, Romania of the liturgical time, where it signals the attempt to merge and reconcile the cosmical solar and lunar cycles within the liturgical year. This leads to a unique theology, expressing the 2Department of Systematic powerful synthesis of the variability of the lunar cycle compared to the structure of the solar and Historical Theology, year’s fixed dates. Faculty of Theology and Religion, University of Contribution: This research reveals the unique orthodox perspective on both civil and Pretoria, Pretoria, liturgical time, expressing their profound theological meaning, as a conscious, permanent South Africa reflection upon the mysterious, yet real, presence of Christ in the divine services of the Church. Research Project Registration: Keywords: liturgical time; orthodoxy; liturgics; anthropology; feast; calendar; Chronos; Kairos. Project Leader: J. -

Sunday of the Publican and the Pharisee: Triodion Begins Today

Saint Barbara Greek Orthodox Church 8306 NC HWY 751, Durham NC 27713 919-484-1600 [email protected], www.stbarbarachurchnc.org News & Announcements, February 5, 2017 Sunday of the Publican and the Pharisee: Triodion Begins Today Agatha the Martyr Polyeuktos, Partriarch Of Constantinople Antonios the New Martyr of Athens Theodosios, Archbishop of Chernigov NEWCOMERS AND VISITORS ARE ALWAYS WELCOME ! Sunday Worship Schedule: Matins 9:00 am & Divine Liturgy 10:00 am To Our Visitors and Guests We welcome you to worship with us today, whether you are an Orthodox Christian or this is your first visit to an Orthodox Church, we are pleased to have you with us. Although Holy Communion and other Sacraments are offered only to baptized and chrismated (confirmed) Orthodox Christians in good standing with the Church, all are invited to receive the Antidoron (blessed bread) from the priest at the conclusion of the Divine Liturgy. The Antidoron is not a sacrament, but it is reminiscent of the agape feast that followed worship in the ancient Christian Church. After the Divine Liturgy this morning please join us in the Church hall for fellowship and refreshments. Please complete a Visitor's Card before you leave today and drop it in the offering tray, or give it to one of the parishioners after the service, or mail it to the church Office. Today's Readings: St. Paul's Second Letter to Timothy 3:10-15 TIMOTHY, my son, you have observed my teaching, my conduct, my aim in life, my faith, my patience, my love, my steadfastness, my persecutions, my sufferings, what befell me at Antioch, at lconion, and at Lystra, what persecutions I endured; yet from them all the Lord rescued me. -

Service Books of the Orthodox Church

SERVICE BOOKS OF THE ORTHODOX CHURCH THE DIVINE LITURGY OF ST. JOHN CHRYSOSTOM THE DIVINE LITURGY OF ST. BASIL THE GREAT THE LITURGY OF THE PRESANCTIFIED GIFTS 2010 1 The Service Books of the Orthodox Church. COPYRIGHT © 1984, 2010 ST. TIKHON’S SEMINARY PRESS SOUTH CANAAN, PENNSYLVANIA Second edition. Originally published in 1984 as 2 volumes. ISBN: 978-1-878997-86-9 ISBN: 978-1-878997-88-3 (Large Format Edition) Certain texts in this publication are taken from The Divine Liturgy according to St. John Chrysostom with appendices, copyright 1967 by the Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church of America, and used by permission. The approval given to this text by the Ecclesiastical Authority does not exclude further changes, or amendments, in later editions. Printed with the blessing of +Jonah Archbishop of Washington Metropolitan of All America and Canada. 2 CONTENTS The Entrance Prayers . 5 The Liturgy of Preparation. 15 The Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom . 31 The Divine Liturgy of St. Basil the Great . 101 The Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts. 181 Appendices: I Prayers Before Communion . 237 II Prayers After Communion . 261 III Special Hymns and Verses Festal Cycle: Nativity of the Theotokos . 269 Elevation of the Cross . 270 Entrance of the Theotokos . 273 Nativity of Christ . 274 Theophany of Christ . 278 Meeting of Christ. 282 Annunciation . 284 Transfiguration . 285 Dormition of the Theotokos . 288 Paschal Cycle: Lazarus Saturday . 291 Palm Sunday . 292 Holy Pascha . 296 Midfeast of Pascha . 301 3 Ascension of our Lord . 302 Holy Pentecost . 306 IV Daily Antiphons . 309 V Dismissals Days of the Week . -

The Date of Pascha/Easter ~ a Message from Fr. Robert

March 2015 ¨1645 Phillips Road, Tallahassee, Florida 32308 ¨ (850) 878-0747 ¨ Rev. Fr. Robert J. O’Loughlin¨ http://www.hmog.org The Date of Pascha/Easter ~ A Message from Fr. Robert It is a typical question that we may be asked in most years is why the Orthodox Church celebrates Pascha on a differ- ent date from other Christian denominations. This year we celebrate Pascha/Easter one week after most other Christians. So I thought once again that we would touch upon this topic of the calculation of when we celebrate Pascha. Our celebration of Pascha was formed from the Jewish Passover. Initially, those Christians converted from Judaism celebrated Pascha in accordance with the Jewish calendar and on the same date of the feast of Passover. “Pascha” was celebrated the 14th of the lunar month of Nisan, regardless of the day of the week upon which it fell. The Church- es of Asia Minor followed this practice while other churches in the east and west celebrated the Feast on the Sunday following this date. By the 3rd century, all the churches were celebrating Pascha on the Sunday following the 14th of Nisan. This determined the Jewish calculation of Passover, which is on the first full moon following the vernal equi- nox. However, following the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD the Jews depended on local pagan calendars for their calculation. So with difficulties with inadequate calendars, the issue of the date of Pascha continued. It was resolved in 325 at the First Ecumenical Council in Nicaea as the early Church Fathers determined the Pascha date to be the first Sunday after the first full moon of the spring equinox. -

The Chronicle of Novgorod 1016-1471

- THE CHRONICLE OF NOVGOROD 1016-1471 TRANSLATED FROM THE RUSSIAN BY ROBERT ,MICHELL AND NEVILL FORBES, Ph.D. Reader in Russian in the University of Oxford WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY C. RAYMOND BEAZLEY, D.Litt. Professor of Modern History in the University of Birmingham AND AN ACCOUNT OF THE TEXT BY A. A. SHAKHMATOV Professor in the University of St. Petersburg CAMDEN’THIRD SERIES I VOL. xxv LONDON OFFICES OF THE SOCIETY 6 63 7 SOUTH SQUARE GRAY’S INN, W.C. 1914 _. -- . .-’ ._ . .e. ._ ‘- -v‘. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE General Introduction (and Notes to Introduction) . vii-xxxvi Account of the Text . xxx%-xli Lists of Titles, Technical terms, etc. xlii-xliii The Chronicle . I-zzo Appendix . 221 tJlxon the Bibliography . 223-4 . 225-37 GENERAL INTRODUCTION I. THE REPUBLIC OF NOVGOROD (‘ LORD NOVGOROD THE GREAT," Gospodin Velikii Novgorod, as it once called itself, is the starting-point of Russian history. It is also without a rival among the Russian city-states of the Middle Ages. Kiev and Moscow are greater in political importance, especially in the earliest and latest mediaeval times-before the Second Crusade and after the fall of Constantinople-but no Russian town of any age has the same individuality and self-sufficiency, the same sturdy republican independence, activity, and success. Who can stand against God and the Great Novgorod ?-Kto protiv Boga i Velikago Novgoroda .J-was the famous proverbial expression of this self-sufficiency and success. From the beginning of the Crusading Age to the fall of the Byzantine Empire Novgorod is unique among Russian cities, not only for its population, its commerce, and its citizen army (assuring it almost complete freedom from external domination even in the Mongol Age), but also as controlling an empire, or sphere of influence, extending over the far North from Lapland to the Urals and the Ob. -

LACHLAN TURNBULL the Man of Sorrows and the King of Glory in Italy, C

Lachlan Turnbull, The Man of Sorrows and the King of Glory in Italy, c. 1250-c. 1350 LACHLAN TURNBULL The Man of Sorrows and the King of Glory in Italy, c. 1250- c. 1350 ABSTRACT The Man of Sorrows – an iconographic type of Jesus Christ following his Crucifixion – has received extensive analytical treatment in the art-historical literature. Following a model that draws scholarly attention to the dynamics of cross-cultural artistic exchange in the central Middle Ages, this article reconsiders recent advances in the scholarly literature and refocusses analysis upon the Man of Sorrows within the context of its ‘shared’ intercultural heritage, suspended between Byzantium and the West, as an image ultimately transformed from liturgical icon to iconographic device. Introduction The image of Jesus’ Crucifixion was originally believed to be either so scandalous, or considered so absurd, that the iconographic means by which to depict it constituted an almost reluctantly-developed theme in Christian art.1 Recent research indicates that Christian Crucifixion iconography emerged in the fourth century and emphasised the salvific – which is to imply, triumphal – aspect of Jesus’ death.2 ‘The Passion’, commencing with the betrayal of Jesus by his disciple Judas Iscariot, culminating in Jesus’ redemptive sacrifice by his Crucifixion and ending with his Resurrection, is a critical narrative in Christian faith.3 The reality of the Crucifixion, including the penetration of Jesus’ side and the issuing of blood and water,4 are pivotal mystic concepts linked to the key Christian doctrines of transubstantiation and sacrificial resurrection, and thus to the efficacy of the Eucharistic Mystery and Christian communion.5 The twinned natures of Jesus, his humanity and divinity, underpin the salvific significance of his death, and the image of his crucified body reinforces the memory of, identification with, and sympathy for Jesus whilst reinforcing the message of his ultimate return. -

Orthodox Mission Methods: a Comparative Study

ORTHODOX MISSION METHODS: A COMPARATIVE STUDY by STEPHEN TROMP WYNN HAYES submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF THEOLOGY in the subject of MISSIOLOGY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA Promoter: Professor W.A. Saayman JUNE 1998 Page 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the University of South Africa, who awarded the Chancellor's Scholarship, which enabled me to travel to Russia, the USA and Kenya to do research. I would also like to thank the Orthodox Christian Mission Center, of St Augustine, Florida, for their financial help in attending the International Orthodox Christian Mission Conference at Holy Cross Seminary, Brookline, MA, in August 1996. To Fr Thomas Hopko, and the staff of St Vladimir's Seminary in New York, for allowing me to stay at the seminary and use the library facilities. The St Tikhon's Institute in Moscow, and its Rector, Fr Vladimir Vorobiev and the staff, for their help with visa applications, and for their patience in giving me information in interviews. To the Danilov Monastery, for their help with accom modation while I was in Moscow, and to Fr Anatoly Frolov and all the parishioners of St Tikhon's Church in Klin, for giving me an insight into Orthodox life and mission in a small town parish. To Metropolitan Makarios of Zimbabwe, and the staff and students of the Makarios III Orthodox Seminary at Riruta, Kenya, for their hospitality and their readiness to help me get the information I needed. To the Pokrov Foundation in Bulgaria, for their hospitality and help, and to the Monastery of St John the Forerunner in Karea, Athens, and many others in that city who helped me with my research in Greece. -

Dating of Easter Differences Between the Eastern and West- Ment Between Eastern and Western Christians

was eventually adopted, whereas in the West in the date of Pascha was the differences in the 2. LENT AND EASTER an eighty-four-year cycle. The use of two dif- calendars and lunar tables (paschal cycles) em- ferent paschal cycles inevitably gave way to ployed rather than any theological disagree- Faith and Life is a new pamphlet series Dating of Easter differences between the Eastern and West- ment between Eastern and Western Christians. that provides an introduction to a wide range In The Orthodox Church ern Churches regarding the observance of In view of the fact that today both the Julian and of spiritual and theological issues. Drawing Pascha. Gregorian modes of calculation diverge from the from the beauty and wisdom of Orthodox astronomical data, it behooves all Christians to Christianity, the series addresses the challenges A further cause for these differences was return to the norms determined by the Council of contemporary life and offers guidance to the adoption by the Western Church of the of Nicaea, taking advantage of the most up-to- help you grow in your relationship with God Gregorian Calendar in 1582 to replace the Ju- date astronomical data for the vernal equinox and in your commitment to His will for your lian Calendar. This took place in order to ad- and the phase of the moon. life. The series is a collaborative effort of the just the discrepancy, then observed between Greek Orthodox Archdiocese Departments the paschal cycle approach to calculating of Church and Society, Communications, Pascha and the available astronomical data. Internet Ministries, Outreach and Evangelism, The Orthodox Church continues to base its Religious Education, and Youth and Young Adult calculations for the date of Pascha on the Ju- Dr. -

Dictionary of Byzantine Catholic Terms

~.~~~~- '! 11 GREEK CATHOLIC -reek DICTIONARY atholic • • By 'Ictionary Rev. Basil Shereghy, S.T.D. and f Rev. Vladimir Vancik, S.T.D. ~. J " Pittsburgh Byzantine Diocesan Press by Rev. Basil Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Shereghy, S.T.D. 1951 • Nihil obstat: To Very Rev. John K. Powell Censor. The Most Reverend Daniel Ivancho, D.D. Imprimatur: t Daniel Ivancho, D.D. Titular Bishop of Europus, Apostolic Exarch. Ordinary of the Pittsburgh Exarchate Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania of the Byzantine.•"Slavonic" Rite October 18, 1951 on the occasion of the solemn blessing of the first Byzantine Catholic Seminary in America this DoaRIer is resf1'eCtfUflY .diditateit Copyright 1952 First Printing, March, 1952 Printed by J. S. Paluch Co•• Inc .• Chicago Greek Catholic Dictionary ~ A Ablution-The cleansing of the Because of abuses, the Agape chalice and the fin,ers of the was suppressed in the Fifth cen• PREFACE celebrant at the DiVIne Liturgy tury. after communion in order to re• As an initial attempt to assemble in dictionary form the more move any particles of the Bless• Akathistnik-A Church book con• common words, usages and expressions of the Byzantine Catholic ed Sacrament that may be ad• taining a collection of akathists. Church, this booklet sets forth to explain in a graphic way the termin• hering thereto. The Ablution Akathistos (i.e., hymns)-A Greek ology of Eastern rite and worship. of the Deacon is performed by term designating a service dur• washmg the palm of the right ing which no one is seated. This Across the seas in the natural home setting of the Byzantine• hand, into .••••.hich the Body of service was originally perform• Slavonic Rite, there was no apparent need to explain the whats, whys Jesus Christ was placed by the ed exclusively in honor of and wherefores of rite and custom. -

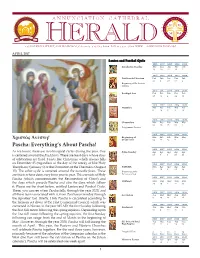

Everything's About Pascha!

April 2017 Herald Χριστὀς Ἀνέέστη! Pascha: Everything’s About Pascha! UNITED GREEK ORTHODOX COMMUNITY OF NON-PROFIT ORG. As we know, there are two liturgical cycles during the year. One is centered around the fixed SAN FRANCISCO, THE ANNUNCIATION U .S. POSTAGE PAID feasts. These are feast days whose days of celebration are fixed. Feasts like Christmas, which ANNUNCI AT I O N CalwaysA fallsT onHEDRA December 25 (regardless L of the day of the week), or like Holy Theophany ANNUNCIATION CATHEDRAL SAN FRANCISCO, CA (January 6) or the Dormition of the Theotokos (August 15). The other cycle is centered around P E R MIT N O. 1 7 3 4 the moveable feasts. These are feasts whose dates vary from year to year. This consists of Holy 245 VALENCIA STREET, SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94103-2320 Pascha (which commemorates the Resurrection of Christ) and the days which precede Pascha and also the days which follow it. Please see the chart below, entitled Lenten and Paschal Cycle. There, you can see when Pascha falls, through the year 2020, and all those feasts associated with it, from Zacchaeus Sunday through the Apostles’ fast. Briefly, Holy Pascha is calculated according to the formula setdown at the First Ecumenical Council, which was convened in Nicaea, in the year 325 AD: the first Sunday following the first full moon following the spring equinox. Depending upon the first full moon following the spring equinox, the first Sunday HERALfollowing can range from the end D of March to the beginning of May. However, through the year 245 VALENCIA STREET, SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94103 • 415 864-80002020, • FAX Pascha 415 will 431-5860 fall during • theWW W month .ANNUNCIATION.ORG of April. -

The Meaning of the Holy Week in the Orthodox Church

THE MEANING OF THE HOLY LENT & HOLY WEEK IN THE ORTHODOX CHURCH Η Μεγάλη Τεσσαρακοστή και η Μεγάλη Εβδομάδα στην Ορθόδοξη Εκκλησία 2015 ASSUMPTION OF THE BLESSED VIRGIN MARY GREEK ORTHODOX CHURCH 5761 E. COLORADO ST. LONG BEACH, CA 90814 “Open to me the gates of repentance, O Giver of Life: for early in the morning my spirit HOLY WEEK SERVICES seeks Your Holy Temple…” (ΛΕΙΤΟΥΡΓΙΕΣ ΤΗΣ ΜΕΓΑΛΗΣ ΕΒΔΟΜΑΔΑΣ) Dearly Beloved, As we commence our annual journey through the Great Fast, the words of this hymn should resound Sunday, 4/5 within us. We began chanting them at the first Sunday of the Triodion and we will continue to hear Των Βαΐων. Palm Sunday. them throughout our Lenten journey as a continual reminder of the purpose of this holy season: repentance or metanoia. During the Lenten season our Orthodox Faith places the tools of repentance in our hands, inviting us to use Orthros 8:45 am. Divine Liturgy 10:00 am them to deepen our relationship with God. The hymn tells us that repentance is found in the holy temple of the Most 1st Bridegroom Service 7:00 pm. (5pm ‐ 7pm Confession) High God. Naturally when we hear “temple” we think of our church and the many Lenten services and programs that areset before us. We can find repentance when we partake of the spiritual banquet of Lenten services and educational opportunities offered in our parishes and participate in them, listen to them, and heed their counsel. Holy Monday, 4/6 Του Νυμφίου. 2nd Bridegroom Service 7:00 pm (5pm ‐ 7pm Confession) During Great Lent, the banquet of holy services replaces, or is intended to replace, the banquets and parties that dominate the rest of the year. -

St. George Greek Orthodox Cathedral Christ Is Risen!

St. George Greek Orthodox Cathedral 650 Hanover Street • Manchester, New Hampshire 03104-5306 Tel. 603.622.9113 • Fax. 603.622.2266 • [email protected] • www.stgeorge.nh.goarch.org A PRIL 2018 the indestructible power and inscrutable wisdom of God. It Christ is risen! disposes of the illusory myths and belief systems by which truly he is risen! people, bereft of divine knowledge, strain to affirm the On the Great and Holy Feast of Pascha, Orthodox Christians meaning and purpose of their existence. Christ, risen and celebrate the life-giving Resurrection of our Lord and Savior glorified, releases humanity from the delusions of idolatry. Jesus Christ. This feast of feasts is the most significant day in In Him grave-bound humanity discovers and is filled with in - the life of the Church. It is a celebration of the defeat of death, comparable hope. The Resurrection bestows illumination, as neither death itself nor the power of the grave could hold energizes souls, brings forgiveness, transfigures lives, cre - our Savior captive. In this victory that came through the Cross, ates saints, and gives joy. Christ broke the bondage of sin, and through faith offers us restoration, transformation, and eternal life. The Resurrection has not yet abolished the reality of death. But it has revealed its powerlessness (Hebrews 2:14-15). We Holy Week comes to an end at sunset of Great and Holy Sat - continue to die as a result of the Fall. Our bodies decay and urday, as the Church prepares to celebrate her most ancient fall away. "God allows death to exist but turns it against cor - and preeminent festival, Pascha, the feast of feasts.