Accuracy in Interpersonal Perception: a Social Relations Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interpersonal Perception of Narcissism in an At-Risk Adolescent Sample: a Social Relations Analysis

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Fall 12-2009 Interpersonal Perception of Narcissism in an At-Risk Adolescent Sample: A Social Relations Analysis Sarah June Grafeman University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Personality and Social Contexts Commons, School Psychology Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Grafeman, Sarah June, "Interpersonal Perception of Narcissism in an At-Risk Adolescent Sample: A Social Relations Analysis" (2009). Dissertations. 1104. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1104 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi INTERPERSONAL PERCEPTION OF NARCISSISM IN AN AT-RISK ADOLESCENT SAMPLE: A SOCIAL RELATIONS ANALYSIS by Sarah June Grafeman A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2009 COPYRIGHT BY SARAH JUNE GRAFEMAN 2009 The University of Southern Mississippi INTERPERSONAL PERCEPTION OF NARCISSISM IN AN AT-RISK ADOLESCENT SAMPLE: A SOCIAL RELATIONS ANALYSIS by Sarah June Grafeman Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2009 ABSTRACT INTERPERSONAL PERCEPTION OF NARCISSISM IN AN AT-RISK ADOLESCENT SAMPLE: A SOCIAL RELATIONS ANALYSIS by Sarah June Grafeman December 2009 The current study utilized Kenny's (1994) social relations model to explore the interpersonal consequences of narcissism in an at-risk adolescent residential sample. -

Self-Concept and Interpersonal Perception Change in Basketball Teams

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1971 Self-concept and interpersonal perception change in basketball teams Richard Alan Wright The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Wright, Richard Alan, "Self-concept and interpersonal perception change in basketball teams" (1971). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5644. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5644 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COPYRIGHT ACT OF 1976 Th is is an unpublished manuscript in which copyright sub s is t s , Any further r epr in tin g of its contents must be approved BY THE AUTHOR. Mansfield Library U niversity of Montana Date: /o/zs/tfc*________ SELF-CONCEPT AND INTERPERSONAL PERCEPTION CHANGE IN BASKETBALL TEAMS By Richard A, Wright B»A. University of Utah, I968 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1971 Approved bys Chairman, Board of Examinees D^an, Graduate School^ UMI Number: EP41108 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Mind Perception Daniel R. Ames Malia F. Mason Columbia

Mind Perception Daniel R. Ames Malia F. Mason Columbia University To appear in The Sage Handbook of Social Cognition, S. Fiske and N. Macrae (Eds.) Please do not cite or circulate without permission Contact: Daniel Ames Columbia Business School 707 Uris Hall 3022 Broadway New York, NY 10027 [email protected] 2 What will they think of next? The contemporary colloquial meaning of this phrase often stems from wonder over some new technological marvel, but we use it here in a wholly literal sense as our starting point. For millions of years, members of our evolving species have gazed at one another and wondered: what are they thinking right now … and what will they think of next? The interest people take in each other’s minds is more than idle curiosity. Two of the defining features of our species are our behavioral flexibility—an enormously wide repertoire of actions with an exquisitely complicated and sometimes non-obvious connection to immediate contexts— and our tendency to live together. As a result, people spend a terrific amount of time in close company with conspecifics doing potentially surprising and bewildering things. Most of us resist giving up on human society and embracing the life of a hermit. Instead, most perceivers proceed quite happily to explain and predict others’ actions by invoking invisible qualities such as beliefs, desires, intentions, and feelings and ascribing them without conclusive proof to others. People cannot read one another’s minds. And yet somehow, many times each day, most people encounter other individuals and “go mental,” as it were, adopting what is sometimes called an intentional stance, treating the individuals around them as if they were guided by unseen and unseeable mental states (Dennett, 1987). -

The Intimacy Motive and Its Relationship to Interpersonal Perception in the Dating Couple

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1984 The Intimacy Motive and Its Relationship to Interpersonal Perception in the Dating Couple Rogelio Rodriguez Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Rodriguez, Rogelio, "The Intimacy Motive and Its Relationship to Interpersonal Perception in the Dating Couple" (1984). Master's Theses. 3399. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/3399 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1984 Rogelio Rodriguez THE INTIMACY MOTIVE AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO INTERPERSONAL PERCEPTION IN THE DATING COUPLE by ROGELIO RODRIGUEZ A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Loyola University of Chicago in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts December, 1984 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I wish to express my appreciation to several people who were of much assistance to me in the completion of this project. I would first like to thank Dr. Dan McAdams, the director of this theses, for all his constant support, help, and general availability throughout every stage of this research project. I am also indebted to Dr. James Johnson for his generous and continuous assistance throughout this project. I would also like to express my sincere thanks to those friends and family who gave me much support and understanding during the entire course of this thesis. -

The Functions of Music-Listening Across Cultures: the Development of a Scale Measuring Personal, Social and Cultural Functions of Music

Grand Valley State University ScholarWorks@GVSU Papers from the International Association for Cross- IACCP Cultural Psychology Conferences 2011 The uncF tions of Music-Listening across Cultures: The evelopmeD nt of a Scale Measuring Personal, Social and Cultural Functions of Music Diana Boer Victoria University of Wellington Ronald Fischer Victoria University of Wellington Jimena de Garay Hernández National Autonomous University of Mexico Ma. Luisa González Atilano National Autonomous University of Mexico Luz Moreno National Autonomous University of Mexico See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/iaccp_papers Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Boer, D., & Fischer, R. (2011). The functions of music-listening across cultures: The development of a scale measuring personal, social and cultural functions of music. In F. Deutsch, M. Boehnke, U. Kuhnë n, & K. Boehnke (EdsRendering borders obsolete: Cross-cultural and cultural psychology as an interdisciplinary, multi-method endeavor: Proceedings from the 19th International Congress of the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology. https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/iaccp_papers/70/ This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the IACCP at ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers from the International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology Conferences by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Diana Boer, Ronald Fischer, Jimena de Garay Hernández, Ma. Luisa González Atilano, Luz Moreno, Marcus Roth, and Markus Zenger This article is available at ScholarWorks@GVSU: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/iaccp_papers/70 207 The Functions of Music-Listening across Cultures: The Development of a Scale Measuring Personal, Social and Cultural Functions of Music Diana Boer & Ronald Fischer Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand In collaboration with (in alphabetical order): Jimena de Garay Hernández, Ma. -

Componential Analysis of Interpersonal Perception Data

Personality and Social Psychology Review Copyright © 2006 by 2006, Vol. 10, No. 4, 282–294 Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Componential Analysis of Interpersonal Perception Data David A. Kenny Tessa V. West Department of Psychology University of Connecticut Thomas E. Malloy Department of Psychology Rhode Island College Linda Albright Department of Psychology Westfield State College We examine the advantages and disadvantages of 2 types of analyses used in interper- sonal perception studies: componential and noncomponential. Componential analy- sis of interpersonal perception data (Kenny, 1994) partitions a judgment into compo- nents and then estimates the variances of and the correlations between these components. A noncomponential analysis uses raw scores to analyze interpersonal perception data. Three different research areas are investigated: consensus of percep- tions across social contexts, reciprocity of attraction, and individual differences in self-enhancement. Finally, we consider criticisms of componential analysis. We con- clude that interpersonal perception data necessarily have components (e.g., per- ceiver, target, measure, and their interactions), and that the researcher needs to de- velop a model that best captures the researcher’s questions. Interpersonal perception, broadly defined as “the searcher might average across measures and targets, study of the beliefs that people have about others” separately for Black and White targets, and compute a (Kenny, 1994, pp. vii), has long been a topic of consid- paired t test to determine if there is a race effect. erable theoretical and empirical interest. The basic data However, not all the questions in interpersonal per- in interpersonal perception minimally contain three ception can be answered by experimental2 methods. key elements: perceivers, targets, and measures. -

Perceiving Others' Personalities

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology © 2010 American Psychological Association 2010, Vol. 98, No. 3, 520–534 0022-3514/10/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0017057 Perceiving Others’ Personalities: Examining the Dimensionality, Assumed Similarity to the Self, and Stability of Perceiver Effects Sanjay Srivastava Steve Guglielmo University of Oregon Brown University Jennifer S. Beer University of Texas at Austin In interpersonal perception, “perceiver effects” are tendencies of perceivers to see other people in a particular way. Two studies of naturalistic interactions examined perceiver effects for personality traits: seeing a typical other as sympathetic or quarrelsome, responsible or careless, and so forth. Several basic questions were addressed. First, are perceiver effects organized as a global evaluative halo, or do perceptions of different traits vary in distinct ways? Second, does assumed similarity (as evidenced by self-perceiver correlations) reflect broad evaluative consistency or trait-specific content? Third, are perceiver effects a manifestation of stable beliefs about the generalized other, or do they form in specific contexts as group-specific stereotypes? Findings indicated that perceiver effects were better described by a differentiated, multidimensional structure with both trait-specific content and a higher order global evaluation factor. Assumed similarity was at least partially attributable to trait-specific content, not just to broad evaluative similarity between self and others. Perceiver effects were correlated with gender and attachment style, but in newly formed groups, they became more stable over time, suggesting that they grew dynamically as group stereotypes. Implications for the interpretation of perceiver effects and for research on personality assessment and psychopathology are discussed. Keywords: social perception, perceiver effects, informant reports, self-perception, Halo effect What a most extraordinary child!” Then she frowned. -

The Relationship Between Interpersonal Perception and Psychological Adjustment

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 12-1978 The Relationship between Interpersonal Perception and Psychological Adjustment Barbara A. Dambach Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Counseling Commons, and the Student Counseling and Personnel Services Commons Recommended Citation Dambach, Barbara A., "The Relationship between Interpersonal Perception and Psychological Adjustment" (1978). Dissertations. 2765. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/2765 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN INTERPERSONAL PERCEPTION AND PSYCHOLOGICAL ADJUSTMENT by Barbara A. Dambach A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the Degree of Doctor of Education Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan December 1978 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to express deep appreciation to Dr. Kenneth Bullmer for his untiring dedication to my work and his unfailing support of me and my efforts. Without his con tinued guidance and encouragement, this study would not have been possible. Dr. Bullmer1s previous work in the field of interpersonal perception also deserves acknowledgment: His research not only provided substantial background for the study, but also served as a constant inspiration. I want to thank both the professional and clerical staff of the Center for Counseling at the University of Delaware for their assistance in implementing this study; their patience and cooperation were invaluable. -

Social Cognitive Neuroscience of Person Perception: a Selective Review Focused on the Event-Related Brain Potential

W&M ScholarWorks Arts & Sciences Book Chapters Arts and Sciences 2007 Social Cognitive Neuroscience of Person Perception: A Selective Review Focused on the Event-Related Brain Potential. Bruce D. Bartholow Cheryl L. Dickter College of William and Mary, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/asbookchapters Part of the Cognition and Perception Commons Recommended Citation Bartholow, B. D., & Dickter, C. L. (2007). Social Cognitive Neuroscience of Person Perception: A Selective Review Focused on the Event-Related Brain Potential.. E. Harmon-Jones & P. Winkielman (Ed.), Social neuroscience: Integrating biological and psychological explanations of social behavior (pp. 376-400). New York, NY: Guilford Press. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/asbookchapters/46 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts and Sciences at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. V PERSON PERCEPTION, STEREOTYPING, AND PREJUDICE Copyright © ${Date}. ${Publisher}. All rights reserved. © ${Date}. ${Publisher}. Copyright 17 Social Cognitive Neuroscience of Person Perception A SELECTIVE REVIEW FOCUSED ON THE EVENT-RELATED BRAIN POTENTIAL Bruce D. Bartholow and Cheryl L. Dickter Although social psychologists have long been interested in understanding the cognitive processes underlying social phenomena (e.g., Markus & Zajonc, 1985), their methods for studying them traditionally have been rather limited. Early research in person perception, like most other areas of social-psychological inquiry, relied primarily on verbal reports. Researchers using this approach have devised clever experimental designs to ensure the validity of their conclusions concerning social behavior (see Reis & Judd, 2000). -

Personality Correlates of Interpersonal Perception in a Residential Treatment Center for Adolescent Girls

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 5-1973 Personality correlates of interpersonal perception in a residential treatment center for adolescent girls Raymond Paul Micciche Portland State University Terrell Lynn Eheler Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Social Control, Law, Crime, and Deviance Commons, Social Psychology Commons, and the Social Psychology and Interaction Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Micciche, Raymond Paul and Eheler, Terrell Lynn, "Personality correlates of interpersonal perception in a residential treatment center for adolescent girls" (1973). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 1728. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.1727 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. PERSONALITY CORHELl>,TES OF INTERPERSONAL PEHCE:E'TION IN A RESIDENTIAL THEATMENr GENTER FOR ADOLESCENT GIRLS ~ RAYMOND PAUL MICCICHE and TBiRRELL LYNN EHELER A practicum submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SOCIAL WORK Portland S·tate Univorsi.ty 1973 This Practicum for the Master of Social Work Degnrn lJy Raymond hrnl Micciche and Terrell Lynn Eheler has been approved May, 1973 Dean; Graduate Schoo-1. of Social Work TABLE Oli1 CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES • . ., . • • • • • • v 1 LIST OF FIGUHES e e e I • I I I e I I I I I I I I I I I I I vi CH.APTb~R I. -

Psychology Graduate Courses 2021-22.Pdf

Department of Psychology Graduate Courses 2021-22 Instructor Semester Area Course Code Course Title Description Schedule Place Opto- and Chemogenetic Neuron The course will survey a variety of genetic neuron manipulation methods being used in the systems neuroscience field, with a particular PSY5121H - Advanced Topics in Kim Fall BN Manipulation - Applications for focus on light-induced neuron manipulation methods and their applications to study a range of cognitive and emotional behaviours and Thu, 2-4 SS 560A Animal Behaviour and Motivation II Understanding Animal Behaviours underlying neural circuitry. This seminar dives into the modern science of moral thought and moral action, explored through the disciplines of cognitive science, Controversies in Moral Psychology: Social, psychology, neuroscience, behavioural economics, and analytic philosophy. Topics include empathy and compassion in babies and young PSY5310H - Advanced Topics in Bloom Fall DEV Developmental, and Cognitive children; the origins of prejudice and bigotry; sexuality, disgust, and purity; punishment, revenge, and forgiveness; dehumanization, and the Mon, 4-6 SS 560A Development I Perspectives relationship between morality and religion. No specific requirements, but participants should be prepared to read, and discuss, articles from a wide range of intellectual disciplines. The brain undergoes significant structural and functional growth during childhood and adolescence. This growth is linked to/underlies the development of cognitive, social, and emotional functions. -

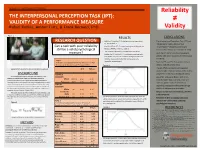

THE INTERPERSONAL PERCEPTION TASK (IPT): VALIDITY of a PERFORMANCE MEASURE ≠ Rafael Robles, Amber Fultz, & Frank Bernieri, Phd Validity

School of Psychological Science Reliability THE INTERPERSONAL PERCEPTION TASK (IPT): VALIDITY OF A PERFORMANCE MEASURE ≠ Rafael Robles, Amber Fultz, & Frank Bernieri, PhD Validity Figure 1 RESULTS CONCLUSIONS RESEARCH QUESTION • Both the IPT and the IPT-15 had poor internal consistency • The Interpersonal Perception Task (IPT) and (< .30; see Table 1) Interpersonal Task 15 (IPT-15) have Can a task with poor reliability • Both the IPT and IPT-15 showed convergent validity with the “unacceptable” reliability according to MSCEIT, DANVA2, PONS (see Table 2) still be a valid psychological classical test theory (Furr & Bacharach, 2008). • The IPT alone significantly correlated with the TAS-20. • Both the IPT and IPT-15 show convergent measure? • Neither the IPT nor the IPT-15 significantly correlated with fully written measures of emotional intelligence (STEU and validity with other measures of interpersonal STEM) or four out of the five BIG-5 personality traits sensitivity Table 1 (exception agreeableness). Published and Sampled Reliability Measures for Two • Both the IPT and IPT-15 show discriminant Versions of the Interpersonal Perception Task Figure 3 validity with personality traits. • The IPT offers a measure with objective Selected item from Costanzo and Archer’s (1989) Interpersonal Perception Task. IPT IPT-15 answers rather than consensus or theoretical n BACKGROUND Published judgments increasing its ecological validity. The Interpersonal Perception Task (IPT) was created by Mark Reliability • Use of IRT analysis on the IPT and IPT-15 Costanzo and Dane Archer (1989) as a naturalistic measure of KR-20 438/530 0.52 0.38 interpersonal sensitivity. The original task included 30 spontaneous show the latter task is, in fact, easier and recordings of two or more people interacting accompanied by a multiple Test-retest 46/52 0.70 0.73 does not gather as much information choice question about the interaction (see Figure 1).