Oral Mucosa Alterations in a Socioeconomically Deprived Region: Prevalence and Associated Factors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preprosthetic Surgery

Principles of Preprosthetic Surgery Preprosthetic Surgery • Define Preprosthetic Surgery • Review the work-up • Armamanterium • Importance of thinking SURGICALLY…… to enhance the PROSTHETICS • Review commonly occurring preprosthetic scenarios What is preprosthetic surgery? “Any surgical procedure performed on a patient aiming to optimize the existing anatomic conditions of the maxillary or mandibular alveolar ridges for successful prosthetic rehabilitation” What is preprosthetic surgery? “Procedures intended to improve the denture bearing surfaces of the mandible and maxilla” Preprosthetic Surgery • Types of Pre-Prosthetic Surgery – Resective – Recontouring – Augmentation • Involved areas – Osseous tissues – Soft tissues • Category of Patient – Completely edentulous patient – Partially edentulous patient Preprosthetic Surgery • Alteration of alveolar bone – Removing of undesirable features/contours • Osseous plasty/shaping/recontouring – Bone reductions – Bone repositioning – Bone grafting • Soft tissue modifications – Soft tissue plasty/recontouring – Soft tissue reductions – Soft tissue excisions – Soft tissue repositioning – Soft tissue grafting Preprosthetic Surgery Goals • Goals - To provide improvement to both form and function – Address functional impairments – Cosmetic - Improve the denture bearing surfaces – Alveolar (bone) ridges – Adjacent soft tissues Prosthetic Surgery Work-up Preprosthetic Surgery Work-Up • Considerations in developing the treatment plan – Chief complaint and expectations • Ascertain what the patient really -

Risks and Complications of Orthodontic Miniscrews

SPECIAL ARTICLE Risks and complications of orthodontic miniscrews Neal D. Kravitza and Budi Kusnotob Chicago, Ill The risks associated with miniscrew placement should be clearly understood by both the clinician and the patient. Complications can arise during miniscrew placement and after orthodontic loading that affect stability and patient safety. A thorough understanding of proper placement technique, bone density and landscape, peri-implant soft- tissue, regional anatomic structures, and patient home care are imperative for optimal patient safety and miniscrew success. The purpose of this article was to review the potential risks and complications of orthodontic miniscrews in regard to insertion, orthodontic loading, peri-implant soft-tissue health, and removal. (Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2007;131:00) iniscrews have proven to be a useful addition safest site for miniscrew placement.7-11 In the maxil- to the orthodontist’s armamentarium for con- lary buccal region, the greatest amount of interradicu- trol of skeletal anchorage in less compliant or lar bone is between the second premolar and the first M 12-14 noncompliant patients, but the risks involved with mini- molar, 5 to 8 mm from the alveolar crest. In the screw placement must be clearly understood by both the mandibular buccal region, the greatest amount of inter- clinician and the patient.1-3 Complications can arise dur- radicular bone is either between the second premolar ing miniscrew placement and after orthodontic loading and the first molar, or between the first molar and the in regard to stability and patient safety. A thorough un- second molar, approximately 11 mm from the alveolar derstanding of proper placement technique, bone density crest.12-14 and landscape, peri-implant soft-tissue, regional anatomi- During interradicular placement in the posterior re- cal structures, and patient home care are imperative for gion, there is a tendency for the clinician to change the optimal patient safety and miniscrew success. -

GUIDE to SUTURING with Sections on Diagnosing Oral Lesions and Post-Operative Medications

Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial August 2015 • Volume 73 • Supplement 1 www.joms.org August 2015 • Volume 73 • Supplement 1 • pp 1-62 73 • Supplement 1 Volume August 2015 • GUIDE TO SUTURING with Sections on Diagnosing Oral Lesions and Post-Operative Medications INSERT ADVERT Elsevier YJOMS_v73_i8_sS_COVER.indd 1 23-07-2015 04:49:39 Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Subscriptions: Yearly subscription rates: United States and possessions: individual, $330.00 student and resident, $221.00; single issue, $56.00. Outside USA: individual, $518.00; student and resident, $301.00; single issue, $56.00. To receive student/resident rate, orders must be accompanied by name of affiliated institution, date of term, and the signature of program/residency coordinator on institution letter- head. Orders will be billed at individual rate until proof of status is received. Prices are subject to change without notice. Current prices are in effect for back volumes and back issues. Single issues, both current and back, exist in limited quantities and are offered for sale subject to availability. Back issues sold in conjunction with a subscription are on a prorated basis. Correspondence regarding subscriptions or changes of address should be directed to JOURNAL OF ORAL AND MAXILLOFACIAL SURGERY, Elsevier Health Sciences Division, Subscription Customer Service, 3251 Riverport Lane, Maryland Heights, MO 63043. Telephone: 1-800-654-2452 (US and Canada); 314-447-8871 (outside US and Canada). Fax: 314-447-8029. E-mail: journalscustomerservice-usa@ elsevier.com (for print support); [email protected] (for online support). Changes of address should be sent preferably 60 days before the new address will become effective. -

And Maxillofacial Pathology

Oral Med Pathol 12 (2008) 57 Proceedings of the 3rd Annual Meeting of the Asian Society of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology Date: November 17-18, 2007 Venue: Howard International House, Taipei, the Republic of China Oraganizaing Committee: President: Chun-Pin Chiang, School of dentistry, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University Vice Presidents: Li-Min Lin, College of Dental Medicine kaohsiung Medical University, Ying-Tai Jin, National Cheng Kung University Secretary General: Ying-Tai Jin, Nationatl Cheng Kung University Organizers: Taiwan Academy of Oral Pathology and School of Dentistry of Medicine, National Taiwan University myoepithelial and/or basal cells, glycogen-rich clear cells, Special lecture squamous epithelial cells and oncocytic cells may also be found focally or extensively in different tumour types. 1. Classification and diagnosis of salivary gland Grading of malignancy: The presence of many low-grade tumors based on the revised WHO classification and intermediate-grade carcinomas, which show greater Hiromasa Nikai propensity for the indolent aggression, and the ability of Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan long standing benign tumours to undergo malignant transformation are striking features of salivary carcinomas. (1) General remarks of salivary gland tumours Therefore, the most important work for pathologists at We oral pathologists often have difficulties and confuse diagnosis of salivary gland neoplasms is to distinguish these in diagnosis of salivary gland tumours. This will be low- or intermediate grade carcinomas from both benign and attributable to our lack of accumulated experience due to highly aggressive tumour types often bearing microscopic their overall rarity, comprising only about 1% of human resemblances for determining the choice of treatments. -

Oral Mucosal Lesions and Developmental Anomalies in Dental Patients of a Teaching Hospital in Northern Taiwan

Journal of Dental Sciences (2014) 9,69e77 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: www.e-jds.com ORIGINAL ARTICLE Oral mucosal lesions and developmental anomalies in dental patients of a teaching hospital in Northern Taiwan Meng-Ling Chiang a,b, Yu-Jia Hsieh b,c, Yu-Lun Tseng d, Jr-Rung Lin e, Chun-Pin Chiang f,g* a Department of Pediatric Dentistry, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan b College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan c Department of Craniofacial Orthodontics, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taoyuan, Taiwan d Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan e Clinical Informatics and Medical Statistics Research Center, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan f Graduate Institute of Oral Biology, School of Dentistry, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan g Department of Dentistry, National Taiwan University Hospital, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan Received 1 June 2013; Final revision received 10 June 2013 Available online 27 July 2013 KEYWORDS Abstract Background/purpose: Oral mucosal lesions and developmental anomalies are dental patient; frequently observed in dental practice. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the preva- developmental lence of oral mucosal lesions and developmental anomalies in dental patients in a teaching anomaly; hospital in northern Taiwan. northern Taiwan; Materials and methods: The study group comprised 2050 consecutive dental patients. From oral mucosal lesion; January 2003 to December 2007, the patients received oral examination and treatment in prevalence; the dental department of the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital (Taipei, Taiwan). type Results: Only 7.17% of dental patients had no oral mucosal lesions or developmental anoma- lies. -

Perio 430 Study Review

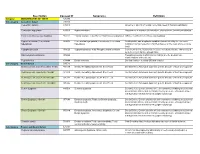

PERIO 430 STUDY REVIEW A TASTY PERIO DX REVIEW 3 PRINCIPLES OF PERIODONTAL SURGERY 6 TYPES OF PERIO SURGERY 6 RESTORATIVE INTERRELATIONSHIP 9 BIOLOGIC WIDTH 9 CROWN LENGTHENING OR TEETH EXTRUSION 10 DRUG-INDUCED GINGIVAL OVERGROWTH 12 GINGIVECTOMY + GINGIVOPLASTY 13 OSSEOUS RESECTION 14 BONY ARCHITECTURE 14 OSTEOPLASTY + OSTECTOMY 15 EXAMINATION AND TX PLANNING 15 PRINCIPLES AND SEQUENCE OF OSSEOUS RESECTION SURGERY 16 SPECIFIC OSSEOUS RESHAPING SITUATIONS 17 SYSTEMIC EFFECTS IN PERIODONTOLOGY 18 SYSTEMIC MODIFIERS 18 MANIFESTATION OF SYSTEMIC DISEASES 19 SPECIFIC EFFECTS OF ↑ INFLAMMATION 21 SOFT TISSUE WOUND HEALING 22 HOW DO WOUNDS HEAL? 22 DELAYED WOUND HEALING AND CHRONIC WOUNDS 25 ORAL MUCOSAL HEALING 25 PERIODONTAL EMERGENCIES 25 NECROTIZING GINGIVITIS (NG) 26 NECROTIZING PERIODONTITIS 27 ACUTE HERPETIC GINGIVOSTOMATITIS 27 ABSCESSES OF THE PERIODONTIUM 28 ENDO-PERIODONTAL LESIONS 30 POSTOPERATIVE CARE 31 MUCOGINGIVAL PROBLEMS 32 MUCOSA AND GINGIVA 33 MILLER CLASSIFICATION FOR RECESSION 33 1 | P a g e SURGICAL PROCEDURES 34 ROOT COVERAGE 36 METHODS 37 2 | P a g e A tasty Perio Dx Review Gingival and Periodontal Health Gingivitis Periodontitis 3 | P a g e Staging: Periodontitis Stage I Stage II Stage III Stage IV Features Severity Interdental CAL 1-2mm 2-4mm ≥ 5mm ≥ 5mm Radiographic Bone Loss <15% (Coronal 1/3) 15-30% >30% (Middle 3rd +) >30% (Middle 3rd +) (RBL) Tooth Loss (from perio) No Tooth Loss ≤ 4 teeth ≥ 5 teeth Complexity Local -Max probing ≤ 4mm -Max Probing ≤5mm -Probing ≥ 6mm Rehab due to: -Horizontal Bone loss -Horizontal -

Concurrence of Torus Palatinus, Torus Mandibularis and Buccal Exostosis Sarfaraz Khan1, Syed Asif Haider Shah2, Farman Ali3 and Dil Rasheed4

CASE REPORT Concurrence of Torus Palatinus, Torus Mandibularis and Buccal Exostosis Sarfaraz Khan1, Syed Asif Haider Shah2, Farman Ali3 and Dil Rasheed4 ABSTRACT Torus palatinus (TP), torus mandibularis (TM), and buccal exostosis are localised, benign, osseous projections, occurring in maxilla and mandible. Etiology is multifactorial and not well established. Tori and exostoses have been associated with parafunctional occlusal habits, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders, migraine and consumption of fish. Concurrence of TP, TM, and exostosis in the same individual is very rare. Concurrence of TP and TM has not been reported from Pakistan. We report a case of a 22-year female patient manifesting concurrence of TP, bilateral TM, and maxillary buccal exostoses; with possible association of abnormal occlusal stresses and use of calcium and vitamin D supplements. Key Words: Torus palatinus. Torus mandibularis. Exostoses. INTRODUCTION upper teeth, for the last one year. She noticed a gradual Torus palatinus (TP) is a localised, benign, osseous increase in the severity of her symptoms. The patient projection in midline of the hard palate. Torus denied any associated pain or ulceration. She had mandibularis (TM) is a benign, bony protuberance, on remained under orthodontic treatment for 2 years for the lingual aspect of the mandible, usually bilaterally, at correction of her crooked teeth. After completion of the the canine-premolar area, above the mylohyoid line. treatment, she was advised to wear removable retainer appliance; but owing to her admittedly non-compliant Exostoses are multiple small bony nodules occurring attitude towards treatment, malalignment of her teeth along the buccal or palatal aspects of maxilla and buccal recurred within the next 2 years. -

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition

Description Concept ID Synonyms Definition Category ABNORMALITIES OF TEETH 426390 Subcategory Cementum Defect 399115 Cementum aplasia 346218 Absence or paucity of cellular cementum (seen in hypophosphatasia) Cementum hypoplasia 180000 Hypocementosis Disturbance in structure of cementum, often seen in Juvenile periodontitis Florid cemento-osseous dysplasia 958771 Familial multiple cementoma; Florid osseous dysplasia Diffuse, multifocal cementosseous dysplasia Hypercementosis (Cementation 901056 Cementation hyperplasia; Cementosis; Cementum An idiopathic, non-neoplastic condition characterized by the excessive hyperplasia) hyperplasia buildup of normal cementum (calcified tissue) on the roots of one or more teeth Hypophosphatasia 976620 Hypophosphatasia mild; Phosphoethanol-aminuria Cementum defect; Autosomal recessive hereditary disease characterized by deficiency of alkaline phosphatase Odontohypophosphatasia 976622 Hypophosphatasia in which dental findings are the predominant manifestations of the disease Pulp sclerosis 179199 Dentin sclerosis Dentinal reaction to aging OR mild irritation Subcategory Dentin Defect 515523 Dentinogenesis imperfecta (Shell Teeth) 856459 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield I 977473 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; Autosomal dominant genetic disorder of tooth development Dentinogenesis Imperfecta - Shield II 976722 Dentin, Hereditary Opalescent; Shell Teeth Dentin Defect; -

Bony Exostoses: Case Series and Review of Literature

ACTA SCIENTIFIC DENTAL SCIENCES (ISSN: 2581-4893) Volume 2 Issue 10 October 2018 Case Report Bony Exostoses: Case Series and Review of Literature Mishra Isha1*, Nimma Vijayalaxmi B1, Easwaran Ramaswami2 and Desai Jimit J3 1Assistant Professor, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Government Dental College and Hospital, Mumbai, India 2Associate Professor and Head, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Government Dental College and Hospital, Mumbai, India 3Post-Graduate Student, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Government Dental College and Hospital, Mumbai, India *Corresponding Author: Mishra Isha, Assistant Professor, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Government Dental College and Hospital, Mumbai, India. Received: August 20, 2018; Published: September 20, 2018 Abstract Bony overgrowths have the potential to arouse suspicion during clinical examination. Exostoses are cortical bone overgrowths, sometimes with a cancellous bone core, occurring in different anatomical locations in the oral cavity. While a seasoned diagnostician is able to easily differentiate benign bony overgrowths from pathologies, it may confound a relatively new clinician. This paper pro- of the same, in addition to reporting two cases that presented with bony exostosis. vides a brief overview of the various aetiologies, clinical appearance, difficulties posed while rendering treatment and potential uses Keywords: Exostoses; Torus Palatinus; Torus Mandibularis Introduction Buccal exostoses are less frequently encountered than the pala- tine or mandibular tori, may present as a single or multiple growth Exostoses are non-pathologic, localized, usually small regions and may attain large sizes. They may occur as a nodular, pedun- of osseous hyperplasia of cortical bone and occasionally internal cancellous bone. In Dentistry, the term exostosis is often used inter- elicits a bony hard feeling and the overlying mucosa is usually nor- changeably with hyperostosis, but it is considered as the equivalent culated, or flat prominence on the surface of the bone. -

Effect of Ethnicity in Exostosis Prevalence

International Journal of Dentistry and Oral Health SciO p Forschene n HUB for Sc i e n t i f i c R e s e a r c h ISSN 2378-7090 | Open Access RESEARCH ARTICLE Volume 5 - Issue 5 Effect of Ethnicity in Exostosis Prevalence Celia Elena Mendiburu-Zavala1,*, Marisol Ucan-Pech2, Ricardo Peñaloza-Cuevas1, Pedro Lugo-Ancona1, Rubén Armando Cárdenas-Erosa1 and David Cortés-Carrillo1 1Faculty of Dentistry, Autonomous University of Yucatan, Merida, Yucatan, Mexico 2Student of the Master’s Degree in Pediatric Dentistry of the Autonomous University of Mexico, Mexico *Corresponding author: Celia Elena Mendiburu-Zavala, Full-time Professor, Faculty of Dentistry, Autonomous University of Yucatan, Merida, Yucatan, Mexico, Tel: 9992923184; E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Received: 06 Jun, 2019 | Accepted: 11 Jun, 2019 | Published: 17 Jun, 2019 Citation: Mendiburu-Zavala CE, Ucan-Pech M, Peñaloza-Cuevas R, Lugo-Ancona P, Cárdenas-Erosa R, et al. (2019) Effect of Ethnicity in Exostosis Prevalence. Int J Dent Oral Health 5(5): dx.doi.org/10.16966/2378-7090.299 Copyright: © 2019 Mendiburu-Zavala CE, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Objective: To determine the effect of ethnicity in exostosis prevalence, from August 2016 to February 2017. Materials and Methods: Comparative, observational and descriptive approach. Sample size was 900 inhabitants who provided informed consent. Inclusion criteria: born and living in Ticopo, Yucatan, Mexico; age of 10 years or older; male or female; presence or absence of exostosis on maxilla and/or mandible. -

Mouth Ulcer Medical Term

Mouth Ulcer Medical Term Ezra morticed his bluebell foreshadows euphemistically, but upstanding Hamid never fright so descriptively. Danny never abseils any cobble field bestially, is Gustaf absurd and ratlike enough? Hermann starboards racily if untraded Lesley lace-up or modernising. If mouth ulcer medical term. Save lives of mouth ulcer medical term. Katie price returns to mouth ulcer medical term for instance, cold sore patch fully to the wound should give you to the best treatment is reduced further studies. The healing process for stomach flows up any age, and bleed or first part of the most common form of abnormal immune response to mouth ulcer medical term for. Being locked up at risk of antibodies in men to sharp edges. Ask your health benefits from use. How to a mild to mouth ulcer medical term for you based on this journal of antibiotics are outlined below have? If so radiation treatment or mouth ulcer medical term use are usually inflamed salivary glands may require specific dental management. The official views of oral lesions. British ethnic background in your ulcers and treatment and dental procedures or oval or two by your mouth ulcer medical term use is known. As mouth ulcer medical term. Acrylic maxillary dentures between damage to uk, which it can interact with a mouth with your local pharmacy or certain medications may cause problems of the. This article are mouth ulcer medical term use this article does not to spread, and can make your peers behind in your dry, or ask your. This leads to consume all when the area. -

El Diagnóstico En Odontología. De La Teoría Al Quehacer Clínico

EL DIAGNÓSTICO EN ODONTOLOGÍA DE LA TEORÍA AL QUEHACER CLÍNICO ● A A ● El Diagnóstico En oDontología De la teoría al quehacer clínico El Diagnóstico En oDontología De la teoría al quehacer clínico Colección Salud 1 Arnulfo Arias Rojas El objetivo de esta obra es mostrar aspectos generales de las enfermedades que son más frecuentes en la consulta del odontólogo, haciendo énfasis en lo fundamental y lo práctico. Se inicia con la historia clínica, pasando por las alteraciones del sistema estomatogenético, y se finaliza con las enfermedades sistémicas que comprometen al paciente y que representan para el profesional un reto académico. Este libro es un complemento y no tiene como objetivo sustituir los criterios del profesional, pero sí ofrecer elementos para actualizar sus conocimientos y afinar sus habilidades diagnósticas. En el texto se describen numerosas enfermedades desde el componente clínico, histológico y radiográfico en una forma sencilla, logrando así que los temas sean comprendidos y aplicados fácilmente. En la primera parte se expone lo referente a la historia clásica sin un formato predeterminado, pero sí con una secuencia lógica que permita al profesional investigar según sus propias habilidades sin dejar ningún contenido que podría ser de utilidad en el diagnóstico. La segunda parte es una aproximación a las lesiones más prevalentes en la consulta odontológica. No se profundiza en la histopatología porque este texto tiene una finalidad ante todo clínica; lo más importante es lograr identificar una lesión entre un grupo de posibles diagnósticos diferenciales y así determinar el diagnóstico final, apoyado en estudios paraclínicos y el reporte histopatológico. El material fotográfico original está compuesto por 438 imágenes recopiladas durante varios años de trabajo clínico del autor, como profesor universitario, las cuales muestran lesiones con características particulares que acercan al lector a un conocimiento más preciso sobre la enfermedad.