UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

570034Bk Hasse 1/9/09 6:05 PM Page 8

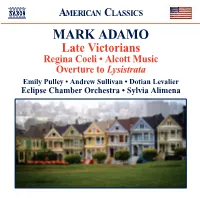

559258bk Adamo:570034bk Hasse 1/9/09 6:05 PM Page 8 Advent as I sat in Most Holy Redeemer SINGER The life we have is very great; Church. The life we are to see AMERICAN CLASSICS Surpasses it because we know SINGER Co-workers. Strangers. Teen-agers. It is infinity. Pensioners. They washed his dishes. But when all space has been beheld VOICE A black man in a checkered sports coat. The And all dominion shown; pink-haired punkess with a jewel in her nose. The smallest human heart’s extent MARK ADAMO The gay couple in middle age. Reduces it to none. SINGER They kissed her on his lips, where once there VOICE These learned to love what is corruptible, Late Victorians were lips. They kissed her on his lips. while I, I, I, I shift my tailbone upon the cold, hard pew. VOICE These know the weight of bodies. Regina Coeli • Alcott Music Finale: Orchestra. Overture to Lysistrata * “Late Victorians” by Richard Rodriguez. Copyright © 1990 by Richard Rodriguez. Originally appeared in Harper’s Magazine (October 1990). By permission of Georges Borchardt, Inc., on behalf of the author. Emily Pulley • Andrew Sullivan • Dotian Levalier Mark Adamo Eclipse Chamber Orchestra • Sylvia Alimena Mark Adamo’s most recent première is Four Angels: Concerto for Harp and Orchestra, introduced by the National Symphony Orchestra in June 2007. His second opera, Lysistrata: or, The Nude Goddess, bowed in March 2006 at New York City Opera, at which Adamo served five years as composer-in-residence. Lysistrata was commissioned and introduced by Houston Grand Opera for its fiftieth season in March 2005. -

Exposing Corruption in Progressive Rock: a Semiotic Analysis of Gentle Giant’S the Power and the Glory

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY Robert Jacob Sivy University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.459 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sivy, Robert Jacob, "EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 149. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/149 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Teaching-Guides; United Womens

DOCUMENT RESUME / ED.227 011, SO 014 467 AUTHOR Bagnall, Carlene; And Others ' - TITLE New Woman, New World: The AmericanExperience. INSTITUTION Michigan Univ., Ann Arbor. Womens Studies Program. SPONS AGENCY National Endowment for the Humanitieg (NFAH), Washington, D.C. ,PUB DATE 77 0. GRANT" EH2-5643-76-772 NOTE 128p. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use -/Guides (For Teachers) (052) p EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indians; Androgyny; Artists; Assertiveness; Blacks; *Family (Sociological Unit); *Females; Feminism; *Health; Higher Education; Immigrants; Interdisciplinary Approach; *Labor Fotce; *Social .tf . Changer *Socialization; Teaching-Guides; United States History; Units of Study; Womens Athletics; Womens Studies ABSTRACT 'A college-level women's studies course on the experience of American women is presented in threeunits onsthe emerging American woman, woman and others, and ,thetranscendent self. Unit 1 focuses on biological and psychologicalexplanations of being female; the socialization process; Black,Native American, and immigra41 women; schooling and its function as IE.-gender-1'01e modifier; and the effect of conflicting forces inone's life. Unit 2 discusses the patriarchal family; the familyin American history; matriarchies, communes, and extended families; women alone andfemale friendshipsrwomen and work in America; and caring forwomen's ,bodies, gouls, and minds. Topics in the finalunit include the status of women, women asLagents of social change,and women AS artists. AthleXics, centering, assertiveness training,and,consciousness raising are also discussed. Materials fromliterature and the social sciences form the focus for each unit,wilich contains an introduction, study questions, and an annotatedlist of required and suggested reading. The appendix includesguidelines for oral history intervi'ews and research paiers. -

London's Symphony Orchestra

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Thursday 12 May 2016 7.30pm Barbican Hall LSO ARTIST PORTRAIT: LEIF OVE ANDSNES Schumann Piano Concerto INTERVAL Beethoven Symphony No 9 (‘Choral’) Michael Tilson Thomas conductor Leif Ove Andsnes piano Lucy Crowe soprano London’s Symphony Orchestra Christine Rice mezzo-soprano Toby Spence tenor Iain Paterson bass London Symphony Chorus Simon Halsey chorus director Concert finishes approx 9.50pm Supported by Baker & McKenzie 2 Welcome 12 May 2016 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief A very warm welcome to tonight’s LSO performance BMW LSO OPEN AIR CLASSICS 2016 at the Barbican. This evening we are joined by Michael Tilson Thomas for his first concert since the The fifth annual BMW LSO Open Air Classics announcement of his appointment as LSO Conductor concert will take place on Sunday 22 May at 6.30pm. Laureate from September 2016, in recognition of Conducted by Valery Gergiev, the LSO will perform his wonderful music-making with the LSO and his an all-Tchaikovsky programme in London’s Trafalgar extraordinary commitment to the Orchestra. We are Square, free and open to all. delighted that his relationship with the LSO will go from strength to strength. lso.co.uk/openair This evening is the second concert in our LSO Artist Portrait series, focusing on pianist Leif Ove Andsnes. LSO AT THE BBC PROMS 2016 Following his performance of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No 20 on Sunday, he returns to play Schumann’s The LSO will be returning to this year’s BBC Proms at Piano Concerto. The Orchestra is also joined this the Royal Albert Hall for a performance of Mahler’s evening by the London Symphony Chorus, led by Symphony No 3 on 29 July. -

Beethoven Symphonies

BEETHOVEN SYMPHONIES MINNESOTA ORCHESTRA OSMO VÄNSKÄ BIS-SACD-1516 BIS-SACD-1516 LvB 3+8 4/19/06 11:10 AM Page 2 van BEETHOVEN, Ludwig (1770-1827) Symphony No. 3 in E flat major, ‘Eroica’, Op. 55 49'54 1 I. Allegro con brio 16'58 2 II. Marcia funebre. Adagio assai 15'07 3 III. Scherzo. Allegro vivace 5'56 4 IV. Finale. Allegro molto – Poco andante – Presto 11'38 Symphony No. 8 in F major, Op. 93 25'25 5 I. Allegro vivace e con brio 9'06 6 II. Allegretto scherzando 4'05 7 III. Tempo di Menuetto 4'48 8 IV. Allegro vivace 7'17 TT: 76'16 Minnesota Orchestra (leader: Jorja Fleezanis) Osmo Vänskä conductor Publisher: Bärenreiter, urtext edition by Jonathan Del Mar BIS-SACD-1516 LvB 3+8 4/19/06 11:10 AM Page 3 eethoven’s Third Symphony is one of the most momentous works in the history of music. It set new standards in size and complexity, at least in Bthe field of instrumental music, and in it the composer advanced so far ahead of his first audience that many of them were left with a feeling of be- wilderment, if not outright hostility – a situation that has since been repeated several times with works of other composers. Where did this new style spring from? Some have seen it as merely a continuation of the path set by Beetho- ven’s Second Symphony, which was also longer and more imposing than any previous symphony. There are indeed some similarities between the two works, such as the opening theme being played by the cellos rather than the violins. -

Central Opera Service Bulletin • Vol

CENTRAL OPERA SERVICE CONFERENCE/BULLETIN Volume 27, Number 1 CENTRAL OPERA SERVICE NATIONAL CONFERENCE AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM la The MetropotttM Opera GaiM'* Fiftieth AwUveray New York - NoTfber Iud2, 015 Sponsored by the Metropolitan Opera National Council Central Opera Service • Lincoln Center • Metropolitan Opera • New York, NY. 10023 • (212) 799-3467 I i ; i Sponsored by the Metropolitan Opera National Council Central Opera Service • Lincoln Center • Metropolitan Opera • New York, N.Y. 10023 • (212)799-346? CENTRAL OPERA SERVICE Volume 27, Number 1 Spring/Summer 1986 CENTRAL OPERA SERVICE NATIONAL CONFERENCE AN INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM In Collaboration With "Opera News" Celebrating The Metropolitan Opera Guild's Fiftieth Anniversary New York - November 1 and 2,1985 This is the special COS Conference issue. The next number will be again a regular news issue with the customary variety of subjects and a performance listing. CENTRAL OPERA SERVICE COMMITTEE Founder MRS. AUGUST BEL MONT (1879-1979) Honorary National Chairman ROBERT L.B. TOBIN National Chairman MRS. MARGO H. B1NDHARDT National Vice Chairman MRS. MARY H. DARRELL Central Opera Service Bulletin • Vol. 27, No. 1 • Spring/Summer 1986 Editor: MARIA F. RICH Assistant Editor: CHERYL KEMPLER Editorial Assistants: LISA VOLPE-REISSIG FRITZI BICKHARDT NORMA LITTON The COS Bulletin is published quarterly for its members by Central Opera Service. Please send any news items suitable for mention in the COS Bulletin as well as performance information to The Editor, Central Opera Service Bulletin, Metropolitan Opera, Lincoln Center, New York, NY 10023. Copies this issue: $12.00 Regular news issues: $3.00 ISSN 0008-9508 TABLE OF CONTENTS Friday, November 1, 1985 WELCOME 1 Margo H. -

Minnesota Orchestra

MINNESOTA ORCHESTRA I Sponsoring assistance by I\!iP Wednesday, May 7, 1986 Orchestra Hall Thursday, May 8, 1986 Ordway Music Theatre Friday, May 9, 1986 Orchestra Hall *Saturday, May 10, 1986 Orchestra Hall 8:00 p.m, SIR NEVILLE MARRINER conducting SUSAN DUNN, soprano JOANNA SIMON, mezzo-soprano KEITH LEWIS, tenor STEPHEN DUPONT, bass DALE WARLAND SYMPHONIC CHORUS Dale Warland, music director Sir Neville Marriner Sigrid Johnson, assistant conductor (Biography appears on page 22.) WAGNER Prelude and Liebestod, from Tristan and Isolde Intermission BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 9 in D minor, Opus 125 (Choral) I. Allegro rna non troppo, un poco maestoso II. Molto vivace- Presto III. Adagio molto e cantabile-Andante moderato IV. Finale: Presto-Allegro; Allegro assai; Presto Susan Dunn Soprano Susan Dunn is remembered by Twin Cities audiences for a variety of per- formances with the Minnesota Orchestra, particularly last Sommerfest's concert presentation of Turandot, when her creation of the role of Uti drew thunder- ous applause. Dunn, an Arkansas native, gained the attention of the music world by winning three prestigious competitions in 1983: the Richard Tucker Award, Chi- Performance time, including intermission, is approximately one hour and 55 minutes. cago's WGN-Illinois Opera Competition *A pension benefit concert. and Dallas' Dealey Competition. She has The Friday evening concert is broadcast livethroughout the region on Minnesota Public subsequently made debuts with such emi- Radio stations, including KSJN-FM (91.1) in the Twin Cities. The H. B. Fuller nent ensembles as the Chicago Lyric Company underwrites the broadcast, which is also heard throughout the country on Opera, as Leonora in La Forza del stations of the American Public Radio Network. -

Music 10378 Songs, 32.6 Days, 109.89 GB

Page 1 of 297 Music 10378 songs, 32.6 days, 109.89 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Ma voie lactée 3:12 À ta merci Fishbach 2 Y crois-tu 3:59 À ta merci Fishbach 3 Éternité 3:01 À ta merci Fishbach 4 Un beau langage 3:45 À ta merci Fishbach 5 Un autre que moi 3:04 À ta merci Fishbach 6 Feu 3:36 À ta merci Fishbach 7 On me dit tu 3:40 À ta merci Fishbach 8 Invisible désintégration de l'univers 3:50 À ta merci Fishbach 9 Le château 3:48 À ta merci Fishbach 10 Mortel 3:57 À ta merci Fishbach 11 Le meilleur de la fête 3:33 À ta merci Fishbach 12 À ta merci 2:48 À ta merci Fishbach 13 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 3:33 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 14 ’¡¢ÁÔé’ 2:29 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 15 ’¡à¢Ò 1:33 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 16 ¢’ÁàªÕ§ÁÒ 1:36 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 17 à¨éÒ’¡¢Ø’·Í§ 2:07 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 18 ’¡àÍÕé§ 2:23 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 19 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 4:00 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 20 áÁèËÁéÒ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ 6:49 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 21 áÁèËÁéÒ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ 6:23 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 22 ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡â€ÃÒª 1:58 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 23 ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ÅéÒ’’Ò 2:55 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 24 Ë’èÍäÁé 3:21 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 25 ÅÙ¡’éÍÂã’ÍÙè 3:55 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 26 ’¡¡ÒàËÇèÒ 2:10 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… 27 ÃÒËÙ≤˨ђ·Ãì 5:24 à≤ŧ¡ÅèÍÁÅÙ¡ªÒÇÊÂÒÁ ʶҺђÇÔ·ÂÒÈÒʵÃì¡ÒÃàÃÕÂ’… -

BRUCKNER SYMPHONY No

OSMO VÄNSKÄ © Ann Marsden BRUCKNER SYMPHONY No. 4 ‘ROMANTIC’ MINNESOTA ORCHESTRA OSMO VÄNSKÄ BIS-SACD-1746 BIS-SACD-1746_f-b.indd 1 10-04-16 11.34.59 BRUCKNER, Anton (1824–96) Symphony No. 4 in E flat major, ‘Romantic’ 62'49 1888 version Edited by Benjamin M. Korstvedt (Int. Bruckner-Gesellschaft Wien) 1 I. Ruhig bewegt (nur nicht schnell) 18'06 2 II. Andante 16'18 3 III. Scherzo. Bewegt – Trio. Gemächlich 9'03 4 IV. Finale. Mäßig bewegt 18'55 Minnesota Orchestra (Jorja Fleezanis leader) Osmo Vänskä conductor 2 The Forgotten Face of Bruckner’s Fourth Symphony Bruckner’s Fourth Symphony, the ‘Romantic’, may be the composer’s most pop ular symphony, yet in a certain sense, it is not fully known. The symphony exists in three distinct versions, only two of which are familiar, even to Bruck - ner aficionados. The first version was composed in 1874 and revised in 1876 but withdrawn by the composer before it could be performed. It was first pub - lished a century later in 1975 and now occupies a secure if secondary place in the canon of Bruckner’s works. The second version was composed between 1878 and 1880, and premièred in February 1881. This is now by far the most often performed version of the symphony. The third version, completed in 1888 and published in 1890, is now much less well-known than its predecessors, yet this was the form in which Bruckner published the symphony and in which it established its reputation as one of the composer’s finest and most com mu nica - tive works. -

1485945431-BIS-9048 Booklet.Pdf

Disc 1 Playing Time: 80'00 SIBELIUS, Johan [Jean] Christian Julius (1865–1957) Kullervo, Op. 7 (1892) (Breitkopf & Härtel) 79'29 for soloists, male-voice choir and orchestra (text: Kalevala) 1 I. Introduction. Allegro moderato 12'46 2 II. Kullervo’s Youth. Grave 19'05 3 III. Kullervo and his Sister. Allegro vivace 25'55 4 IV. Kullervo Goes to War. Alla marcia [Allegro molto] – Vivace – Presto 9'41 5 V. Kullervo’s Death. Andante 11'19 2 Disc 2 Playing Time: 34'05 KORTEKANGAS, Olli (b. 1955) Migrations (2014) (Fennica Gehrman) 25'22 for mezzo-soprano, male voice choir and orchestra (text: Sheila Packa) Commissioned by the Minnesota Orchestra · Recorded in the presence of the composer 1 I. Two Worlds 3'40 2 II. First Interlude 2'57 3 III. Resurrection 5'10 4 IV. Second Interlude 3'27 5 V. The Man Who Lived in a Tree 2'19 6 VI. Third Interlude 3'29 7 VII. Music That We Breathe 4'20 SIBELIUS, Jean 8 Finlandia, Op. 26 (1899, rev.1900) (Breitkopf & Härtel) 8'19 with choir participation (text: V.A. Koskenniemi) TT: 114'05 YL Male Voice Choir Pasi Hyökki chorus-master Minnesota Orchestra Erin Keefe leader Osmo Vänskä conductor Lilli Paasikivi mezzo-soprano · Tommi Hakala baritone 3 Jean Sibelius: Kullervo · Finlandia The Kalevala, Finland’s national epic in fifty ‘runos’ (‘poems’), was assembled by Elias Lönnrot, a doctor, from Karelian folk originals and published in 1835; a revised edition followed in 1849. It would be difficult to overestimate the impact of this remark able work on Finnish culture at all levels, especially during the years when Finland, a Grand Duchy of the Russian Empire, found its autonomy under increasing threat – a period that broadly coincided with the early part of Sibelius’s active career as a composer. -

Vanguard Label Discography Was Compiled Using Our Record Collections, Schwann Catalogs from 1953 to 1982, a Phono-Log from 1963, and Various Other Sources

Discography Of The Vanguard Label Vanguard Records was established in New York City in 1947. It was owned by Maynard and Seymour Solomon. The label released classical, folk, international, jazz, pop, spoken word, rhythm and blues and blues. Vanguard had a subsidiary called Bach Guild that released classical music. The Solomon brothers started the company with a loan of $10,000 from their family and rented a small office on 80 East 11th Street. The label was started just as the 33 1/3 RPM LP was just gaining popularity and Vanguard concentrated on LP’s. Vanguard commissioned recordings of five Bach Cantatas and those were the first releases on the label. As the long play market expanded Vanguard moved into other fields of music besides classical. The famed producer John Hammond (Discoverer of Robert Johnson, Bruce Springsteen Billie Holiday, Bob Dylan and Aretha Franklin) came in to supervise a jazz series called Jazz Showcase. The Solomon brothers’ politics was left leaning and many of the artists on Vanguard were black-listed by the House Un-American Activities Committive. Vanguard ignored the black-list of performers and had success with Cisco Houston, Paul Robeson and the Weavers. The Weavers were so successful that Vanguard moved more and more into the popular field. Folk music became the main focus of the label and the home of Joan Baez, Ian and Sylvia, Rooftop Singers, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Doc Watson, Country Joe and the Fish and many others. During the 1950’s and early 1960’s, a folk festival was held each year in Newport Rhode Island and Vanguard recorded and issued albums from the those events. -

Undigitized Photo Index

People States-Towns-Countries General Subjects Railroad Companies Denver People Abeyta Family Abbott, Emma Abbott, Hellen Abbott, Stephen S. Abernathy, Ralph (Rev.) Abreu, Charles Acheson, Dean Gooderham Acker, Henry L. Adair, Alexander Adami, Charles and Family Adams, Alva (Gov.) Adams, Alva Blanchard (Sen.) Adams, Alva Blanchard (Mrs. Elizabeth Matty) Adams, Alva Blanchard Jr. Adams, Andy Adams, Charles Adams, Charles Partridge Adams, Frederick Atherton and Family Adams, George H. Adams, James Capen (―Grizzly‖) Adams, James H. and Family Adams, John T. Adams, Johnnie Adams, Jose Pierre Adams, Louise T. Adams, Mary Adams, Matt Adams, Robert Perry Adams, Mrs. Roy (―Brownie‖) Adams, W. H. Adams, William Herbert and Family Addington, March and Family Adelman, Andrew Adler, Harry Adriance, Jacob (Rev. Dr.) and Family Ady, George Affolter, Frederick Agnew, Spiro T. Aichelman, Frank and Family Aicher, Cornelius and Family Aiken, John W. Aitken, Leonard L. Akeroyd, Richard G. Jr. Alberghetti, Carla Albert, John David (―Uncle Johnnie‖) Albi, Charles and Family Albi, Rudolph (Dr.) Alda, Frances Aldrich, Asa H. Alexander, D. M. Alexander, Sam (Manitoba Sam) Alexis, Alexandrovitch (Grand Duke of Russia) Alford, Nathaniel C. Alio, Giusseppi Allam, James M. Allegretto, Michael Allen, Alonzo Allen, Austin (Dr.) Allen, B. F. (Lt.) Allen, Charles B. Allen, Charles L. Allen, David Allen, George W. Allen, George W. Jr. Allen, Gracie Allen, Henry (Guide in Middle Park-Not the Henry Allen of Early Denver) Allen, John Thomas Sr. Allen, Jules Verne Allen, Orrin (Brick) Allen, Rex Allen, Viola Allen William T. Jr. (Col.) Allison, Clay Allott, Gordon L. Allott, Gordon L. (Mrs. Welda Hall) Almirall, Leon V.