Ben Murray (Parlku-Nguyu-Thangka Yiwarna )

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adelaide Benevolent and Strangers' Friend Society (Elder Hall)

Heritage of the City of Adelaide ADELAIDE BENEVOLENT AND STRANGERS' FRIEND SOCIETY (ELDER HALL) 17 Morialta Street Elder Hall has considerable historical significance being identified with the Adelaide Benevolent and Strangers' Friend Society, founded in 1849. This society is reputedly the oldest secular philanthropic society, in South Australia, its chief work being to provide housing for the poor. The South Australian Register, 28 February 1849 described relief to the sick and indigent, especially among newly arrived immigrants; and promoting the moral and spiritual welfare of the recipients and their children. The article went on to point out that: It was formerly, said there were no poor in South Australia. This was perfectly true in the English sense of the word; but there was always room for the exercise of private charity" and now, we regret to say, owing to some injudicious selections of emigrants by the [Colonization] commissioners, and the uninvited and gratuitous influx of unsuitable colonists, who having managed to pay their own passages, land in a state of actual destitution, we have now a number of unexpected claimants for whom something must be done. In response the society stated that emigrants exhausted their meagre funds paying for necessaries in England for passage to the colony. Landing without means of support while they searched for work, they ' . .were reduced to great distress by their inability to pay the exorbitant weekly rents demanded for the most humble shelters' Often the society paid their rent for a short time and this assistance, together with rations from the Destitute Board, ' . enabled many deserving but indigent persons to surmount the unexpected and unavoidable difficulties attending their first arrival in a strange land', In 1981 the Advertiser reported that the society had just held its 131st annual meeting quietly, as usual, seldom making headlines, never running big television appeals. -

ORNITHOLOGIST VOLUME 44 - PARTS 1&2 - November - 2019

SOUTH AUSTRALIAN ORNITHOLOGIST VOLUME 44 - PARTS 1&2 - November - 2019 Journal of The South Australian Ornithological Association Inc. In this issue: Variation in songs of the White-eared Honeyeater Phenotypic diversity in the Copperback Quailthrush and a third subspecies Neonicotinoid insecticides Bird Report, 2011-2015: Part 1, Non-passerines President: John Gitsham The South Australian Vice-Presidents: Ornithological John Hatch, Jeff Groves Association Inc. Secretary: Kate Buckley (Birds SA) Treasurer: John Spiers FOUNDED 1899 Journal Editor: Merilyn Browne Birds SA is the trading name of The South Australian Ornithological Association Inc. Editorial Board: Merilyn Browne, Graham Carpenter, John Hatch The principal aims of the Association are to promote the study and conservation of Australian birds, to disseminate the results Manuscripts to: of research into all aspects of bird life, and [email protected] to encourage bird watching as a leisure activity. SAOA subscriptions (e-publications only): Single member $45 The South Australian Ornithologist is supplied to Family $55 all members and subscribers, and is published Student member twice a year. In addition, a quarterly Newsletter (full time Student) $10 reports on the activities of the Association, Add $20 to each subscription for printed announces its programs and includes items of copies of the Journal and The Birder (Birds SA general interest. newsletter) Journal only: Meetings are held at 7.45 pm on the last Australia $35 Friday of each month (except December when Overseas AU$35 there is no meeting) in the Charles Hawker Conference Centre, Waite Road, Urrbrae (near SAOA Memberships: the Hartley Road roundabout). Meetings SAOA c/o South Australian Museum, feature presentations on topics of ornithological North Terrace, Adelaide interest. -

Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks

Department for Environment and Heritage Heritage of the Birdsville and Strzelecki Tracks Part of the Far North & Far West Region (Region 13) Historical Research Pty Ltd Adelaide in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd Lyn Leader-Elliott Iris Iwanicki December 2002 Frontispiece Woolshed, Cordillo Downs Station (SHP:009) The Birdsville & Strzelecki Tracks Heritage Survey was financed by the South Australian Government (through the State Heritage Fund) and the Commonwealth of Australia (through the Australian Heritage Commission). It was carried out by heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd, in association with Austral Archaeology Pty Ltd, Lyn Leader-Elliott and Iris Iwanicki between April 2001 and December 2002. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia and they do not accept responsibility for any advice or information in relation to this material. All recommendations are the opinions of the heritage consultants Historical Research Pty Ltd (or their subconsultants) and may not necessarily be acted upon by the State Heritage Authority or the Australian Heritage Commission. Information presented in this document may be copied for non-commercial purposes including for personal or educational uses. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above requires written permission from the South Australian Government or the Commonwealth of Australia. Requests and enquiries should be addressed to either the Manager, Heritage Branch, Department for Environment and Heritage, GPO Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001, or email [email protected], or the Manager, Copyright Services, Info Access, GPO Box 1920, Canberra, ACT, 2601, or email [email protected]. -

Chapter 18 Non-Aboriginal Cultural Heritage

NON-ABORIGINAL CULTURAL HERITAGE 18 18.1 InTRODUCTION During the 1880s, the South Australian Government assisted the pastoral industry by drilling chains of artesian water wells Non-Aboriginal contact with the region of the EIS Study Area along stock routes. These included wells at Clayton (on the began in 1802, when Matthew Flinders sailed up Spencer Gulf, Birdsville Track) and Montecollina (on the Strzelecki Track). naming Point Lowly and other areas along the shore. Inland The government also established a camel breeding station at exploration began in the early 1800s, with the primary Muloorina near Lake Eyre in 1900, which provided camels for objective of finding good sheep-grazing land for wool police and survey expeditions until 1929. production. The region’s non-Aboriginal history for the next 100 years was driven by the struggle between the economic Pernatty Station was established in 1868 and was stocked with urge to produce wool and the limitations imposed by the arid sheep in 1871. Other stations followed, including Andamooka environment. This resulted in boom/crash cycles associated in 1872 and Arcoona and Chances Swamp (which later became with periods of good rains or drought. Roxby Downs) in 1877 (see Chapter 9, Land Use, Figures 9.3 18 and 9.4 for location of pastoral stations). A government water Early exploration of the Far North by Edward John Eyre and reserve for travelling stock was also established further south Charles Sturt in the 1840s coincided with a drought cycle, in 1882 at a series of waterholes called Phillips Ponds, near and led to discouraging reports of the region, typified by what would later be the site of Woomera. -

Rare Books Lib

RBTH 2239 RARE BOOKS LIB. S The University of Sydney Copyright and use of this thesis This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copynght Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act gran~s the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author's moral rights if you: • fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work • attribute this thesis to another author • subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author's reputation For further information contact the University's Director of Copyright Services Telephone: 02 9351 2991 e-mail: [email protected] Camels, Ships and Trains: Translation Across the 'Indian Archipelago,' 1860- 1930 Samia Khatun A thesis submitted in fuUUment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History, University of Sydney March 2012 I Abstract In this thesis I pose the questions: What if historians of the Australian region began to read materials that are not in English? What places become visible beyond the territorial definitions of British settler colony and 'White Australia'? What past geographies could we reconstruct through historical prose? From the 1860s there emerged a circuit of camels, ships and trains connecting Australian deserts to the Indian Ocean world and British Indian ports. -

Well Maintained Bores Last Longer

November 2015 Issue 75 ACROSS THE OUTBACK Montecollina Bore Well maintained bores last longer The SAAL NRM Board would like to remind water users in the 01 BOARD NEWS SA Arid Lands region who have a bore under their care and 01 Well maintained bores last longer control to undertake simple, routine maintenance to reduce 02 LEB partnership wins world’s highest river management honour risks to water supplies, prevent costly and inconvenient 04 LAND MANAGEMENT breakdowns, and to meet their legal obligations. 04 Innovative ‘Spatial Hub’ lands in The region’s largest water resource is the The review of 289 artesian bores in the Far South Australia Great Artesian Basin (GAB) which provides North Prescribed Wells Area was undertaken 05 Grader workshops help fight soil a vital supply of groundwater for the to establish a comprehensive picture of the erosion continued operation of our key industries condition of the artesian bores in South 06 Women’s Retreat hailed a success (tourism, pastoral, mining, gas and Australia. petroleum) and to meet the needs of our It highlighted that maintenance needs to 07 THREATENED SPECIES communities and wildlife. improve. 07 Are Ampurtas making a comeback? To safeguard the sustainability of the In recent decades, governments, industry 08 SA ARID LANDS – IT’S YOUR GAB and other groundwater aquifers the and individuals have invested significantly PLACE Far North Prescribed Wells Area Water in bore rehabilitation and installing piped Allocation Plan was adopted in 2009 after a reticulation systems to deliver GAB water 12 VOLUNTEERS planning process led by the Board under the efficiently. -

Moore.Corruption of Benjamin Boothby

[2013] ANZLH E-Journal, Refereed Paper No 2 The Corruption of Benjamin Boothby Peter Moore Law, University of Technology Sydney ABSTRACT The fifteen-year judicial career of Justice Boothby of the Supreme Court of South Australia all but annulled the colony’s constitutional foundations. A contemporary declared that his honour was ‘literally at war with every institution in the colony’.1 Historians have studied the legal reasoning he deployed to strike down local legislation and legal administration and have analysed its consequences for colonial law, governance and enterprise. As a result, we know a great deal about what Boothby did and the effect he had. Less has been said about what Alex Castles called Boothby’s ‘personal moral justification’.2 This paper concludes that Benjamin Boothby benefited from money received indirectly from a litigant before him. Writing Boothby The Boothby saga has been told well and often. Its modern historiography began with Ralph Hague’s narrative-style ‘Early history of the law in South Australia’. His chapter on Boothby, the largest in the opus, he finished typing around 1936. He expanded and revised it in 1961 and re- worked it a little more by 1992. The latter version has dominated most of the subsequent work on the subject though, unaccountably, it remains unpublished.3 Meanwhile the ‘Bothby case’ attracted a string of commentators. A paper by A. J. Hannan Q. C. set the ball rolling in 1957.4 Castles prepared Boothby’s 1969 ADB entry and, with Michael Harris in 1987, surveyed Boothby’s legal and political impacts in their full colonial context.5 As recently as 1 Advertiser, 11 March 1867, 2 (repeated at ‘Supreme Confusion’: Chronicle, 16 March 1867, 4). -

Western Australian Explorations

40 "EARLY DAYS"-JOURNAL AND PROCEEDINGS Western Australian Explorations By Mr. fI. J. S. WISE, M.L.A. (Read before the Historical Society, 31/7/42) I fully appreciate the honour and privilege heroes are made to appear nothing less of addressing the Western Australian Histori than demigods. It seems because the tales cal Society on this occasion. I make no 01 Australian travel and self-devotion are claim to address you as an authority, and true, that they attract but little notice, lor can speak to you only as a student over a were the narratives 01 the explorers not number of years 01 the many explorations true we might become the most renowned which have contributed to the establishmenl novelists the world has ever known. Again, of what we now regard as Auslralian geo Australian geography, as explained in the graphy. works of Australian exploration, might be called an unlearned study. Let me ask Among my very earliest recollections as a how many boys out 01 a hundred in Aus child, I have the memory of Sir A. C. Gregory tralia, or England either, have ever react who was such a tremendous contributor to Sturt or Mitchell, Eyre, Leichhardt, Grey or our knowledge 01 this country and who for Stuart It is possible a few may have read years prior to his death, lived at Toowong, Cook's voyages, because they appear Brisbane. This may have been the founda more national, but who has read Flinders, tion of a strong interest in such matters and Kfng or Stokes? Is it because these nar prompted the reading 01 much of our history. -

BARR SMITH LIBRARY University of Adelaide

Heritage of the City of Adelaide BARR SMITH LIBRARY University of Adelaide Off North Terrace This classically derived building is in stark contrast to Walter Hervey Bagot's other university building, the Bonython Hall, which was built in the mediaeval Gothic style. The library, of red-brick, stone dressings and freestone portico, is reminiscent of Georgian England, imposing, but elegant. It has also been likened to similar buildings at Harvard University. The original library complex dominates the main university lawns opposite the Victoria Drive Gates, enhanced by mature trees, and blends with the various other buildings also in red-brick and of this century. The Barr Smith Library is a memorial to Robert Barr Smith who from 1892 bequeathed large sums of money to purchase books for the university library. After his death in 1915 the family made the maintenance of the Library its concern. Following his father, Thomas Elder Barr Smith became a member of the council in 1924 and offered £20 000 for a new library to relieve the congested state of the one in the Mitchell Building. He increased his gift to cover the expected building cost of £34 000. Walter Bagot chose a classic style for the proposed library. The pamphlet describing the official opening of the Barr Smith Library stated that: The tradition that the mediaeval styles are appropriate to educational buildings dies hard; but it is dying. Climate is the dominant factor, and a mediterranean climate such as this should predispose us to a mediterranean, that is to say, a classic form of architecture . -

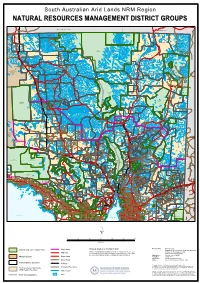

Natural Resources Management District Groups

South Australian Arid Lands NRM Region NNAATTUURRAALL RREESSOOUURRCCEESS MMAANNAAGGEEMMEENNTT DDIISSTTRRIICCTT GGRROOUUPPSS NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Mount Dare H.S. CROWN POINT Pandie Pandie HS AYERS SIMPSON DESERT RANGE SOUTH Tieyon H.S. CONSERVATION PARK ALTON DOWNS TIEYON WITJIRA NATIONAL PARK PANDIE PANDIE CORDILLO DOWNS HAMILTON DEROSE HILL Hamilton H.S. SIMPSON DESERT KENMORE REGIONAL RESERVE Cordillo Downs HS PARK Lambina H.S. Mount Sarah H.S. MOUNT Granite Downs H.S. SARAH Indulkana LAMBINA Todmorden H.S. MACUMBA CLIFTON HILLS GRANITE DOWNS TODMORDEN COONGIE LAKES Marla NATIONAL PARK Mintabie EVERARD PARK Welbourn Hill H.S. WELBOURN HILL Marla - Oodnadatta INNAMINCKA ANANGU COWARIE REGIONAL PITJANTJATJARAKU Oodnadatta RESERVE ABORIGINAL LAND ALLANDALE Marree - Innamincka Wintinna HS WINTINNA KALAMURINA Innamincka ARCKARINGA Algebuckinna Arckaringa HS MUNGERANIE EVELYN Mungeranie HS DOWNS GIDGEALPA THE PEAKE Moomba Evelyn Downs HS Mount Barry HS MOUNT BARRY Mulka HS NILPINNA MULKA LAKE EYRE NATIONAL MOUNT WILLOUGHBY Nilpinna HS PARK MERTY MERTY Etadunna HS STRZELECKI ELLIOT PRICE REGIONAL CONSERVATION ETADUNNA TALLARINGA PARK RESERVE CONSERVATION Mount Clarence HS PARK COOBER PEDY COMMONAGE William Creek BOLLARDS LAGOON Coober Pedy ANNA CREEK Dulkaninna HS MABEL CREEK DULKANINNA MOUNT CLARENCE Lindon HS Muloorina HS LINDON MULOORINA CLAYTON Curdimurka MURNPEOWIE INGOMAR FINNISS STUARTS CREEK SPRINGS MARREE ABORIGINAL Ingomar HS LAND CALLANNA Marree MUNDOWDNA LAKE CALLABONNA COMMONWEALTH HILL FOSSIL MCDOUAL RESERVE PEAK Mobella -

Cultural Illumination

Art & Heritage Collections Peter Drew Cultural Faces of the University Illumination In the tradition of great street art Peter Drew, artist, University of Adelaide graduate and current Masters student, has saturated the Campus with the fabulous faces of the University greats of old. Art & Heritage Collections invite you to take a stroll on campus and peer into its secret corners… Enjoy discovering the Faces of the University! For more information please contact Art & Heritage Collections on 83033086 or email [email protected]. If you are keen to know more about the University history and the faces around the Campus we invite you to buy a newly published book The Spirit of Knowledge: A Social History of the University of Adelaide North Terrace Campus written by Rob Linn and published by Barr Smith Press. To secure an order form contact Diane Todd on 83037090 or email [email protected] For more information please email [email protected] images contoured and supplied by Peter Drew, from the University of Adelaide Archives Collection Thanks to University Archives and Property Infrastructure and Technology for their enthusiastic support for the project and Division of Services and Resources for their continued support. A&H Archibald Watson Charles Schilsky Dame Roma Mitchell Edith Dornwell First Professor of Anatomy Teacher of Violin at the Graduate of the University of The first woman graduated by at the University of Adelaide Elder Conservatorium Adelaide, outstanding scholar, the University of Adelaide in foremost -

MARREE - INNAMINCKA Natural Resources Management Group

South Australian Arid Lands NRM Region MARREE - INNAMINCKA Natural Resources Management Group NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND SIMPSON DESERT CONSERVATION PARK Pastoral Station ALTON DOWNS MULKA PANDIE PANDIE Boundary CORDILLO DOWNS Conservation and National Parks Regional reserve/ SIMPSON DESERT Pastoral Station REGIONAL RESERVE Aboriginal Land Marree - Innamincka CLIFTON HILLS NRM Group COONGIE LAKES NATIONAL PARK INNAMINCKA REGIONAL RESERVE SA Arid Lands NRM Region Boundary INNAMINCKA Dog Fence COWARIE Major Road MACUMBA ! KALAMURINA Innamincka Minor Road / Track MUNGERANIE Railway GIDGEALPA ! Moomba Cadastral Boundary THE PEAKE Watercourse LAKE EYRE (NORTH) LAKE EYRE MULKA Mainly Dry Lake NATIONAL PARK MERTY MERTY STRZELECKI ELLIOT PRICE REGIONAL CONSERVATION RESERVE PARK ETADUNNA BOLLARDS ANNA CREEK LAGOON DULKANINNA MULOORINA LINDON LAKE BLANCHE LAKE EYRE (SOUTH) MULOORINA CLAYTON MURNPEOWIE Produced by: Resource Information, Department of Water, Curdimurka ! STRZELECKI Land and Biodiversity Conservation. REGIONAL Data source: Pastoral lease names and boundaries supplied by FINNISS MARREE RESERVE Pastoral Program, DWLBC. Cadastre and Reserves SPRINGS LAKE supplied by the Department for Environment and CALLANNA ABORIGINAL ! Marree CALLABONNA Heritage. Waterbodies, Roads and Place names LAND FOSSIL supplied by Geoscience Australia. STUARTS CREEK MUNDOWDNA Projection: MGA Zone 53. RESERVE Datum: Geocentric Datum of Australia, 1994. MOOLAWATANA MOUNT MOUNT LYNDHURST FREELING FARINA MULGARIA WITCHELINA UMBERATANA ARKAROOLA WALES SOUTH NEW