BUTTERFLY SURVEYS ARE IMPACTED by TIME of DAY Butterfly Surveys Are Commonly Used to Monitor the Abundance and Diversity of Butt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insect Survey of Four Longleaf Pine Preserves

A SURVEY OF THE MOTHS, BUTTERFLIES, AND GRASSHOPPERS OF FOUR NATURE CONSERVANCY PRESERVES IN SOUTHEASTERN NORTH CAROLINA Stephen P. Hall and Dale F. Schweitzer November 15, 1993 ABSTRACT Moths, butterflies, and grasshoppers were surveyed within four longleaf pine preserves owned by the North Carolina Nature Conservancy during the growing season of 1991 and 1992. Over 7,000 specimens (either collected or seen in the field) were identified, representing 512 different species and 28 families. Forty-one of these we consider to be distinctive of the two fire- maintained communities principally under investigation, the longleaf pine savannas and flatwoods. An additional 14 species we consider distinctive of the pocosins that occur in close association with the savannas and flatwoods. Twenty nine species appear to be rare enough to be included on the list of elements monitored by the North Carolina Natural Heritage Program (eight others in this category have been reported from one of these sites, the Green Swamp, but were not observed in this study). Two of the moths collected, Spartiniphaga carterae and Agrotis buchholzi, are currently candidates for federal listing as Threatened or Endangered species. Another species, Hemipachnobia s. subporphyrea, appears to be endemic to North Carolina and should also be considered for federal candidate status. With few exceptions, even the species that seem to be most closely associated with savannas and flatwoods show few direct defenses against fire, the primary force responsible for maintaining these communities. Instead, the majority of these insects probably survive within this region due to their ability to rapidly re-colonize recently burned areas from small, well-dispersed refugia. -

Pine Island Ridge Management Plan

Pine Island Ridge Conservation Management Plan Broward County Parks and Recreation May 2020 Update of 1999 Management Plan Table of Contents A. General Information ..............................................................................................................3 B. Natural and Cultural Resources ...........................................................................................8 C. Use of the Property ..............................................................................................................13 D. Management Activities ........................................................................................................18 E. Works Cited ..........................................................................................................................29 List of Tables Table 1. Management Goals…………………………………………………………………21 Table 2. Estimated Costs……………………………………………………………….........27 List of Attachments Appendix A. Pine Island Ridge Lease 4005……………………………………………... A-1 Appendix B. Property Deeds………….............................................................................. B-1 Appendix C. Pine Island Ridge Improvements………………………………………….. C-1 Appendix D. Conservation Lands within 10 miles of Pine Island Ridge Park………….. D-1 Appendix E. 1948 Aerial Photograph……………………………………………………. E-1 Appendix F. Development Agreement………………………………………………….. F-1 Appendix G. Plant Species Observed at Pine Island Ridge……………………………… G-1 Appendix H. Wildlife Species Observed at Pine Island Ridge ……... …………………. H-1 Appendix -

St.Marks National Wildlife Refuge Butterfly Checklist

St.Marks National Wildlife Refuge Butterfly Checklist Assembled by Stacy Hurst, Richard G. RuBino, and Karla Brandt September 2002 Sponsored by the St. Marks Refuge Association, Inc. For more information on butterflies and other wildlife on the refuge, contact: St. Marks NationalWildlife Refuge 1255 Lighthouse Road, St. Marks, FL 32355 (850) 925-6121 http://saintmarks.fws.gov Sunset photo by Shawn Gillette, St. Marks NWR Inside photographs are reproduced by permission of Paul A. Opier l^ong-tailed Skipper (Urbanusproteus) - May-Nov; brushy or disturbed areas Silver-spotted Skipper (Epargyreus clarus) - Mar-Oct; open areas Milkweed Butterflies Monarch (Danaus plexippus) - Apr & Oct-Nov; open fields; clusters in trees ©Paul A. Opler ©Paul A Opler ©Paul A Opler ©Paul A. Opler Queen (Danaus gilippus) - Apr-Sep; open areas, brushy fields, roadsides Zebra Swallowtail Palamedes Swallowtail Gulf Fritillary American Lady Other Butterflies This checklist includes the most common species of butterflies found at St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge, the time of year they might be seen on the American Lady (Vanessa virginiensis) - Mar-May & Sep-Oct; open spaces refuge, and their habitat preferences. Carolina Satyr (Hermeuptychia sosybius) - Mar-Nov; open fields, wooded Swallowtails areas Black Swallowtail (Papilio polyxenes) - Jun-Nov; open fields, tidal Common Buckeye (Junonia coenia) - May-Nov; open fields, pine woods marshes Common Wood Nymph (Cercyonis pegala) -May-Sep; moist, grassy areas Eastern Tiger Swallowtail (Papilio glaucus) - Apr-Nov; edge of Common Buckeye deciduous woods Gemmed Satyr (Cyllopsis gemma) - May-Nov; moist grassy areas Giant Swallowtail (Papilio cresphontes) - Apr-Oct; woodlands and fields Georgia Satyr (Neonympha areolata) - Mar-Apr & Sep-Oct; open pine OPaul A. -

Butterflies of Citrus County and Host Plants

Butterflies of Citrus County ~---4- --•;... ____ - Family I Species Host plant Hesperiidae SkipQers Phocides Qigmalion Mangrove Skipper ~mangrove herbs, vines, shrubs, and trees in the pea family (Fabaceae) including false indigobush (Amorpha fruticosa L.), American hogpeanut (Amphicarpaea bracteata [L.) Fernald), Atlantic pidgeonwings or butterfly pea (Clitoria mariana L.), groundnut (Apios ~vreus clarus Silver-spotted Skip~ americana Medik.), American wisteria (Wisteria frutescens [L.) Poir.) and the introduced Dixie ticktrefoil (Desmodium tortuosum [Sw.] DC.), kudzu (Pueraria montana [Lour.] Merr.), black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.), Chinese wisteria (Wisteria sinensis [Sims) DC.) and a variety of other legumes Urbanus prqJg_µs Long-t~.Ued SkiQpec vine legumes including various beans (Phaseolus), hog peanuts (Amphicarpa bracteata), beggar's ticks (Desmodium), blue peas (Clitoria), and wisteria (Wisteria) Various legumes inclu ding wild and cu ltivated beans (Phaseolus), begga r's ticks Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail (Desmodium), and bl ue peas (Clit oria ) -· Beggar\'s ticks (Desmodium); occasionally false indigo (Baptisia) and bush clover Achalarus ly-ciades Hoar.y_r;_ggg {Lespedeza); all in the pea family {Fabaceae) - pea family (Fabaceae) including beggar's ticks (Desmodium), bush clover (Lespedeza), Thor'lbes P'llades Northern Cloud'lwing clover (Trifolium), lotus (Hosackia), and others. -----· Thory-bes bathy-llus Southern Cloudywing Potato bean, Apios americana. Ozark milkvetch, Astragalus distortus var. engelmanni ~ ---- Lespedezas (Lespedeza spp .) are reported as well as Florida Hoarypea (Tephrosia l ibQr:_y_bes confusis Confused Cloudy-wing florid a) . -· -- -------- Staphy:lus hayhurst_ii Ha yh u r?J?-5.IAJ.\QQ Wi ri_g Lambsquart ers {Che nopodium) in the goosefoot family (Chenopodiaceae ), and occasiona lly chaff flower (Alternanthera) in the pigweed family (Amaranthaceae). -

How to Use This Checklist

How To Use This Checklist Swallowtails: Family Papilionidae Special Note: Spring and Summer Azures have recently The information presented in this checklist reflects our __ Pipevine Swallowtail Battus philenor R; May - Sep. been recognized as separate species. Azure taxonomy has not current understanding of the butterflies found within __ Zebra Swallowtail Eurytides marcellus R; May - Aug. been completely sorted out by the experts. Cleveland Metroparks. (This list includes all species that have __ Black Swallowtail Papilio polyxenes C; May - Sep. __ Appalachian Azure Celastrina neglecta-major h; mid - late been recorded in Cuyahoga County, and a few additional __ Giant Swallowtail Papilio cresphontes h; rare in Cleveland May; not recorded in Cuy. Co. species that may occur here.) Record you observations and area; July - Aug. Brush-footed Butterflies: Family Nymphalidae contact a naturalist if you find something that may be of __ Eastern Tiger Swallowtail Papilio glaucus C; May - Oct.; __ American Snout Libytheana carinenta R; June - Oct. interest. females occur as yellow or dark morphs __ Variegated Fritillary Euptoieta claudia R; June - Oct. __ Spicebush Swallowtail Papilio troilus C; May - Oct. __ Great Spangled Fritillary Speyeria cybele C; May - Oct. Species are listed taxonomically, with a common name, a Whites and Sulphurs: Family Pieridae __ Aphrodite Fritillary Speyeria aphrodite O; June - Sep. scientific name, a note about its relative abundance and flight __ Checkered White Pontia protodice h; rare in Cleveland area; __ Regal Fritillary Speyeria idalia X; no recent Ohio records; period. Check off species that you identify within Cleveland May - Oct. formerly in Cleveland Metroparks Metroparks. __ West Virginia White Pieris virginiensis O; late Apr. -

An Annotated List of the Butterflies and Skippers of Lawrence County, Ohio

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 39( 4). 1985. 284-298 AN ANNOTATED LIST OF THE BUTTERFLIES AND SKIPPERS OF LAWRENCE COUNTY, OHIO JOHN V. CALHOUN 6332 C Ambleside Dr., Columbus, Ohio 43229 ABSTRACT. Until recently, only 23 species of butterflies and skippers were known from Lawrence County. In 1983-1984 a study was conducted to increase our knowledge of these insects in the county. As a result, 60 additional species were recorded. One species, Euchloe olympia, was recorded in Ohio for the first time. For each species listed, the following data are provided: relative abundance, habitat and nectar sources, extreme dates, and localities. Species recorded prior to this study are accompanied by historic collection data. A list of 21 additional species which should be looked for in Lawrence County is included. Twenty-four species are not known from the adjacent counties in Kentucky or West Virginia. Thirteen species showed differences in abundance between 1983 and 1984 and potential reasons are discussed. Curves are also provided to illustrate relative species diversity during the study. The county possesses characteristics more typical of regions to the south of Ohio and the Appalachian uplands, and several resident species of butterflies and skippers reflect these aspects. A list of species found in Lawrence County, Ohio allows for a more complete understanding of the butterfly and skipper fauna of southern Ohio, northeastern Kentucky and southwestern West Virginia. Two lists have dealt with the butterflies and skippers of southeastern Ohio (Parshall, 1983; Shuey, 1983). Although Vinton and Athens coun ties have received attention, other counties in the region have virtually been ignored. -

Amblyscirtes: Problems with Species, Species Groups, the Limits of the Genus, and Genus Groups Beyond-A Look at What Is Wrong Wi

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Soctety 44(1), 1990, 11-27 AMBLYSCIRTES: PROBLEMS WITH SPECIES, SPECIES GROUPS, THE LIMITS OF THE GENUS, AND GENUS GROUPS BEYOND-A LOOK AT WHAT IS WRONG WITH THE SKIPPER CLASSIFICATION OF EV ANS (HESPERIIDAE) JOHN M. BURNS Department of Entomology, NHB 169, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. 20560 ABSTRACT. In detecting and correcting errors at all these taxonomic levels, I lean heavily on genitalia. Two similar, closely related, ostensibly allopatric differentiates treated by some as species and by others as subspecies are indeed separate species that are barely sympatric: Amblyscirtes celia Skinner and A. belli Freeman. Most closely related to this pair is the mainly Mexican complex A. tolteca Scudder / prenda Evans, rather different in facies and currently misplaced in a different species group of Amblyscirtes. Another species that looks very like an Amblyscirtes-simius Edwards-assuredly is not! Although, like simius, A. alternata (Grote & Robinson) has a short, blunt antenna I apiculus that is "wrong" for Amblyscirtes, alternata clearly belongs. Placed by Evans (1955) in his N or Lerodea group of American hesperiine genera and said to be allied to Atrytonopsis, Lerodea, and Oligoria, Amblyscirtes actually has close ties with various neotropical genera in Evans's J or Apaustus group: Remella, Mnasicles, and Callimormus! By extrapolation, much of Evans's taxonomic system just below the level of the subfamily may be invalid. Ironically, a Guatemalan skipper that Bell (1959) described in the J group genus Moeris (with which Evans erroneously synonymized Remella) is really an Amblyscirtes: A. patriciae, new combination. -

Butterflies Swan Island

Checkerspots & Crescents Inornate Ringlet ↓ Coenonympha tullia The Ringlet has a Harris’s Checkerspot Chlosyne harrisii bouncy, irregular Pearl Crescent ↓ Phyciodes tharos flight pattern. Abundant in open Crescents fly from fields from late May May to October. to early October. Especially common Common Wood Nymph ↓ Cercyonis pegala on dirt roads. Pearl and Northern hard The Common to differentiate. Wood Nymph is Northern Pearl Crescent Phyciodes cocyta very abundant. Flies from July to Eastern Comma Polygonia comma Sept. along wood Mourning Cloak Nymphalis antiopa edges and fields. Red Admiral Vanessa atalanta ______________________________________ Butterflies American Lady ↓ Vanessa virginiensis ______________________________________ of ______________________________________ American Lady found on dirt Swan Island roads and open Perkins TWP, Maine patches in fields. Steve Powell Wildlife Flight period is April to October. Management Area White Admiral Limenitis arthemis Viceroy Limenitis archippus ______________________________________ ______________________________________ Satyrs Great Spangled Fritillary Northern Pearly-Eye Enodia anthedon Eyed Brown ↓ Satyrodes eurydice Eyed Brown found in wet, wooded Swan Island – Explore with us! www.maine.gov/swanisland edges. Has erratic Maine Butterfly Survey flight pattern. Flies Checklist and brochure created by Robert E. mbs.umf.maine.edu from late June to Gobeil and Rose Marie F. Gobeil in cooperation with the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries Photos of Maine Butterflies early August. www.mainebutterflies.com and Wildlife (MDIFW). Photos by Rose Marie F. Gobeil Little Wood Satyr Megisto cymela ______________________________________ SECOND PRINTING: APRIL 2019 Skippers Pepper & Salt Skipper Amblyscirtes hegon Banded Hairstreak ↓ Satyrium calanus Swallowtails Banded Hairstreak: Silver-spotted Skipper ↓Epargyreus clarus uncommon, found Silver-spotted Black Swallowtail Papilio polyxenes in open glades in Skipper is large Canadian Tiger Swallowtail ↓ Papilio canadensis wooded areas. -

Coastal Butterflies & Host Plants

GIANT SKIPPERS Family: Hesperiidae, Subfamily: Megathymi- nae Yucca Giant-Skipper: Megathymus yuccae Host: Yuccas (Yucca aloifolia, Y. gloriosa, Y. fila- mentosa, Y. flaccida) Carolina Satyr S. Pearly-eye Gemmed Satry Viola’s Wood-Satyr Horace’s Duskywing by Gosse Silver-spotted Skipper nectaring on pickerlweed Butterflies need native host plants to complete SATYRS their life cycle. The larvae of many species can Family: Nymphalidae, Subfamily: Satyrinae only survive on specific plants; think of mon- Southern Pearly-eye: Enodia portlandia * archs and milkweeds, longwings and passion- Host: Switchcane (Arundinaria tecta) flowers. The host plants listed here are native to the coastal region of Georgia & South Caro- Creole Pearly Eye: Enodia creola Delaware Skipper Long-tailed Skipper Host: Switchcane (Arundinaria tecta) lina. They provide a critical link for butterfly survival. Protect native plants in your landscape Appalachian Brown: Satyrodes appalachia and grow them in your gardens to support Host: Carex spp., Rhynchospora spp. these important pollinators. Gemmed Satyr: Cyllopsis gemma * Host: Woodoats (Chasmanthium laxum, C. ses- siliflorum) Sachem Skipper Whirlabout Skipper Carolina Satyr: Hermeuptychia sosybius * Host: St. Augustine (Stenotaphrum secundatum) Georgia Satyr: Neonympha areolata Host: Sawgrass (Cladium jamaicense), Sedges (Cyperaceae) Fiery Skipper Checkered Skipper Provided by Coastal WildScapes Little Wood Satyr: Megisto cymela * Twin-spotted Skipper Lace-winged Roadside (www.coastalwildscapes.org) Host: St. Augustine -

Butterflies of the Niobrara Valley Preserve, Nebraska

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societies Nebraska Academy of Sciences 1988 Butterflies of the Niobrara Valley Preserve, Nebraska Neil E. Dankert Kearney State College Harold G. Nagel Kearney State College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tnas Part of the Life Sciences Commons Dankert, Neil E. and Nagel, Harold G., "Butterflies of the Niobrara Valley Preserve, Nebraska" (1988). Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societies. 179. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tnas/179 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nebraska Academy of Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences and Affiliated Societiesy b an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. 1988. Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences, XVI: 17-30. BUTTERFLIES OF THE NIOBRARA VALLEY PRESERVE, NEBRASKA Neil E. Dankert and Harold G. Nagel Department of Biology Kearney State College Kearney, Nebraska 68849 Seventy species of butterflies and skippers are reported from the Niobrara METHODS Valley Preserve. Twenty-four new county records are added to Brown County while 42 are added to the Keya Paha County checklist, bringing the total The Niobrara Valley Preserve is a 20,800 ha (52,000 acre) species/county to 63 and 67 respectively. Notes on numbers, flight periods, natural area located in north-central Nebraska. The Preserve is and habitat preferences are presented for each of the seventy species found on the Preserve. -

Species List for Garey Park-Inverts

Species List for Garey Park-Inverts Category Order Family Scientific Name Common Name Abundance Category Order Family Scientific Name Common Name Abundance Arachnid Araneae Agelenidae Funnel Weaver Common Arachnid Araneae Thomisidae Misumena vatia Goldenrod Crab Spider Common Arachnid Araneae Araneidae Araneus miniatus Black-Spotted Orbweaver Rare Arachnid Araneae Thomisidae Misumessus oblongus American Green Crab Spider Common Arachnid Araneae Araneidae Argiope aurantia Yellow Garden Spider Common Arachnid Araneae Uloboridae Uloborus glomosus Featherlegged Orbweaver Uncommon Arachnid Araneae Araneidae Argiope trifasciata Banded Garden Spider Uncommon Arachnid Endeostigmata Eriophyidae Aceria theospyri Persimmon Leaf Blister Gall Rare Arachnid Araneae Araneidae Gasteracantha cancriformis Spinybacked Orbweaver Common Arachnid Endeostigmata Eriophyidae Aculops rhois Poison Ivy Leaf Mite Common Arachnid Araneae Araneidae Gea heptagon Heptagonal Orbweaver Rare Arachnid Ixodida Ixodidae Amblyomma americanum Lone Star Tick Rare Arachnid Araneae Araneidae Larinioides cornutus Furrow Orbweaver Common Arachnid Ixodida Ixodidae Dermacentor variabilis American Dog Tick Common Arachnid Araneae Araneidae Mangora gibberosa Lined Orbweaver Uncommon Arachnid Opiliones Sclerosomatidae Leiobunum vittatum Eastern Harvestman Uncommon Arachnid Araneae Araneidae Mangora placida Tuft-legged Orbweaver Uncommon Arachnid Trombidiformes Anystidae Whirligig Mite Rare Arachnid Araneae Araneidae Mecynogea lemniscata Basilica Orbweaver Rare Arachnid Eumesosoma roeweri -

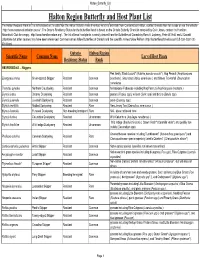

Halton Region Butterfly and Host Plant List

Halton_Butterfly_List Halton Region Butterfly and Host Plant List The Halton Regional Rank in this list is based on the data from the Halton Natural Areas Inventory which is available from Conservation Halton, contact Brenda Axon for a copy or see the website : http://www.conservationhalton.on.ca/ . The Ontario Residency Status for the butterflies listed is based on the Ontario Butterfly Checklist compiled by Colin Jones, contact the Hamilton Naturalists' Club for a copy : http://www.hamiltonnature.org/ . The list of larval host plants is mostly derived from the Butterflies of Canada by Ross A. Layberry, Peter W. Hall, and J. Donald Lafontaine but other sources may have been referenced. Common names follow Butterflies of Canada and the scientific names follow Pelham (http://butterfliesofamerica.com/US-Can-Cat-1-30- 2011.htm). Ontario Halton Region Scientific Name Common Name Larval Host Plants Residency Status Rank HESPERIIDAE – Skippers Pea family; Black Locust* (Robinia pseudo-acacia* ), Hog Peanut (Amphicarpaea Epargyreus clarus Silver-spotted Skipper Resident Common bracteata ), Groundnut (Apios americana ), and Showy Tick-trefoil (Desmodium canadense ) Thorybes pylades Northern Cloudywing Resident Common herbaciouse Fabaceae including Hog Peanut (Amphicarpaea bracteata ) Erynnis icelus Dreamy Duskywing Resident Common poplars (Poplus spp), willows (Salix spp) and birchs (Betula spp) Erynnis juvenalis Juvenal's Duskywing Resident Common oaks (Quercus spp) Erynnis martialis Mottled Duskywing Resident Rare New Jersey Tea (Ceanothus