John Abbot's Butterfly Drawings for William Swainson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panicledleaf Ticktrefoil (Desmodium Paniculatum) Plant Fact Sheet

Plant Fact Sheet Hairstreak (Strymon melinus) eat the flowers and PANICLEDLEAF developing seedpods. Other insect feeders include many kinds of beetles, and some species of thrips, aphids, moth TICKTREFOIL caterpillars, and stinkbugs. The seeds are eaten by some upland gamebirds (Bobwhite Quail, Wild Turkey) and Desmodium paniculatum (L.) DC. small rodents (White-Footed Mouse, Deer Mouse), while Plant Symbol = DEPA6 the foliage is readily eaten by White-Tailed Deer and other hoofed mammalian herbivores. The Cottontail Contributed by: USDA, NRCS, Norman A. Berg National Rabbit also consumes the foliage. Plant Materials Center, Beltsville, MD Status Please consult the PLANTS Web site and your State Department of Natural Resources for this plant’s current status (e.g. threatened or endangered species, state noxious status, and wetland indicator values). Description and Adaptation Panicledleaf Ticktrefoil is a native, perennial, wildflower that grows up to 3 feet tall. The genus Desmodium: originates from Greek meaning "long branch or chain," probably from the shape and attachment of the seedpods. The central stem is green with clover-like, oblong, multiple green leaflets proceeding singly up the stem. The showy purple flowers appear in late summer and grow arranged on a stem maturing from the bottom upwards. In early fall, the flowers produce leguminous seed pods approximately ⅛ inch long. Panicledleaf Photo by Rick Mark [email protected] image used with permission Ticktrefoil plants have a single crown. This wildflower is a pioneer species that prefers some disturbance from Alternate Names wildfires, selective logging, and others causes. The sticky Panicled Tick Trefoil seedpods cling to the fur of animals and the clothing of Uses humans and are carried to new locations. -

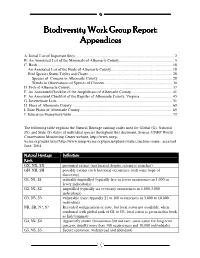

Biodiversity Work Group Report: Appendices

Biodiversity Work Group Report: Appendices A: Initial List of Important Sites..................................................................................................... 2 B: An Annotated List of the Mammals of Albemarle County........................................................ 5 C: Birds ......................................................................................................................................... 18 An Annotated List of the Birds of Albemarle County.............................................................. 18 Bird Species Status Tables and Charts...................................................................................... 28 Species of Concern in Albemarle County............................................................................ 28 Trends in Observations of Species of Concern..................................................................... 30 D. Fish of Albemarle County........................................................................................................ 37 E. An Annotated Checklist of the Amphibians of Albemarle County.......................................... 41 F. An Annotated Checklist of the Reptiles of Albemarle County, Virginia................................. 45 G. Invertebrate Lists...................................................................................................................... 51 H. Flora of Albemarle County ...................................................................................................... 69 I. Rare -

Uncus Shaped Akin to Elephant Tusks Defines a New Genus for Two Very Different-In-Appearance Neotropical Skippers (Hesperiidae: Pyrginae)

The Journal Volume 45: 101-112 of Research on the Lepidoptera ISSN 0022-4324 (PR in T ) THE LEPIDOPTERA RESEARCH FOUNDATION, 29 DE C EMBER 2012 ISSN 2156-5457 (O N L in E ) Uncus shaped akin to elephant tusks defines a new genus for two very different-in-appearance Neotropical skippers (Hesperiidae: Pyrginae) Nic K V. GR ishin Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Departments of Biophysics and Biochemistry, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd, Dallas, TX, USA 75390-9050 [email protected] Abstract. Analyses of male genitalia, other aspects of adult, larval and pupal morphology, and DNA COI barcode sequences suggest that Potamanaxas unifasciata (C. Felder & R. Felder, 1867) does not belong to Potamanaxas Lindsey, 1925 and not even to the Erynnini tribe, but instead is more closely related to Milanion Godman & Salvin, 1895 and Atarnes Godman & Salvin, 1897, (Achlyodini). Unexpected and striking similarities are revealed in the male genitalia of P. unifasciata and Atarnes hierax (Hopffer, 1874). Their genitalia are so similar and distinct from the others that one might casually mistake them for the same species. Capturing this uniqueness, a new genus Eburuncus is erected to include: E. unifasciata, new combination (type species) and E. hierax, new combination. Key words: phylogenetic classification, monophyletic taxa, immature stages, DNA barcodes,Atarnes sallei, Central America, Peru. INTRODUCT I ON 1982-1999). Most of Burns’ work derives from careful analysis of genitalia, recently assisted by morphology Comprehensive work by Evans (e.g. Evans, 1937; of immature stages and molecular evidence (e.g. 1952; 1953) still remains the primary source of Burns & Janzen, 2005; Burns et al., 2009; 2010). -

Butterflies of the Wesleyan Campus

BUTTERFLIES OF THE WESLEYAN CAMPUS SWALLOWTAILS Hairstreaks (Subfamily - Theclinae) (Family PAPILIONIDAE) Great Purple Hairstreak - Atlides halesus Coral Hairstreak - Satyrium titus True Swallowtails Banded Hairstreak - Satyrium calanus (Subfamily - Papilioninae) Striped Hairstreak - Satyrium liparops Pipevine Swallowtail - Battus philenor Henry’s Elfin - Callophrys henrici Zebra Swallowtail - Eurytides marcellus Eastern Pine Elfin - Callophrys niphon Black Swallowtail - Papilio polyxenes Juniper Hairstreak - Callophrys gryneus Giant Swallowtail - Papilio cresphontes White M Hairstreak - Parrhasius m-album Eastern Tiger Swallowtail - Papilio glaucus Gray Hairstreak - Strymon melinus Spicebush Swallowtail - Papilio troilus Red-banded Hairstreak - Calycopis cecrops Palamedes Swallowtail - Papilio palamedes Blues (Subfamily - Polommatinae) Ceraunus Blue - Hemiargus ceraunus Eastern-Tailed Blue - Everes comyntas WHITES AND SULPHURS Spring Azure - Celastrina ladon (Family PIERIDAE) Whites (Subfamily - Pierinae) BRUSHFOOTS Cabbage White - Pieris rapae (Family NYMPHALIDAE) Falcate Orangetip - Anthocharis midea Snouts (Subfamily - Libytheinae) American Snout - Libytheana carinenta Sulphurs and Yellows (Subfamily - Coliadinae) Clouded Sulphur - Colias philodice Heliconians and Fritillaries Orange Sulphur - Colias eurytheme (Subfamily - Heliconiinae) Southern Dogface - Colias cesonia Gulf Fritillary - Agraulis vanillae Cloudless Sulphur - Phoebis sennae Zebra Heliconian - Heliconius charithonia Barred Yellow - Eurema daira Variegated Fritillary -

Lepidoptera of North America 5

Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Lepidoptera of North America 5. Contributions to the Knowledge of Southern West Virginia Lepidoptera by Valerio Albu, 1411 E. Sweetbriar Drive Fresno, CA 93720 and Eric Metzler, 1241 Kildale Square North Columbus, OH 43229 April 30, 2004 Contributions of the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity Colorado State University Cover illustration: Blueberry Sphinx (Paonias astylus (Drury)], an eastern endemic. Photo by Valeriu Albu. ISBN 1084-8819 This publication and others in the series may be ordered from the C.P. Gillette Museum of Arthropod Diversity, Department of Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO 80523 Abstract A list of 1531 species ofLepidoptera is presented, collected over 15 years (1988 to 2002), in eleven southern West Virginia counties. A variety of collecting methods was used, including netting, light attracting, light trapping and pheromone trapping. The specimens were identified by the currently available pictorial sources and determination keys. Many were also sent to specialists for confirmation or identification. The majority of the data was from Kanawha County, reflecting the area of more intensive sampling effort by the senior author. This imbalance of data between Kanawha County and other counties should even out with further sampling of the area. Key Words: Appalachian Mountains, -

The Genome Sequence of the Ringlet, Aphantopus Hyperantus

Edinburgh Research Explorer The genome sequence of the ringlet, Aphantopus hyperantus Linnaeus 1758 Citation for published version: Mead, D, Saccheri, I, Yung, CJ, Lohse, K, Lohse, C, Ashmole, P, Smith, M, Corton, C, Oliver, K, Skelton, J, Betteridge, E, Quail, MA, Dolucan, J, McCarthy, SA, Howe, K, Wood, J, Torrance, J, Tracey, A, Whiteford, S, Challis, R, Durbin, R & Blaxter, M 2021, 'The genome sequence of the ringlet, Aphantopus hyperantus Linnaeus 1758', Wellcome Open Research, vol. 6, no. 165. https://doi.org/10.12688/wellcomeopenres.16983.1 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.16983.1 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Wellcome Open Research General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 06. Oct. 2021 Wellcome Open Research 2021, 6:165 Last updated: 29 JUN 2021 DATA NOTE The genome sequence of the ringlet, Aphantopus hyperantus Linnaeus 1758 [version 1; peer review: awaiting peer review] Dan Mead 1,2, Ilik Saccheri3, Carl J. -

Bibliographic Guide to the Terrestrial Arthropods of Michigan

The Great Lakes Entomologist Volume 16 Number 3 - Fall 1983 Number 3 - Fall 1983 Article 5 October 1983 Bibliographic Guide to the Terrestrial Arthropods of Michigan Mark F. O'Brien The University of Michigan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle Part of the Entomology Commons Recommended Citation O'Brien, Mark F. 1983. "Bibliographic Guide to the Terrestrial Arthropods of Michigan," The Great Lakes Entomologist, vol 16 (3) Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/tgle/vol16/iss3/5 This Peer-Review Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Great Lakes Entomologist by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. O'Brien: Bibliographic Guide to the Terrestrial Arthropods of Michigan 1983 THE GREAT LAKES ENTOMOLOGIST 87 BIBLIOGRAPHIC GUIDE TO THE TERRESTRIAL ARTHROPODS OF MICHIGAN Mark F. O'Brienl ABSTRACT Papers dealing with distribution, faunal extensions, and identification of Michigan insects and other terrestrial arthropods are listed by order, and cover the period of 1878 through 1982. The following bibliography lists the publications dealing with the distribution or identification of insects and other terrestrial arthropods occurring in the State of Michigan. Papers dealing only with biological, behavioral, or economic aspects are not included. The entries are grouped by orders, which are arranged alphabetically, rather than phylogenetic ally , to facilitate information retrieval. The intent of this paper is to provide a ready reference to works on the Michigan fauna, although some of the papers cited will be useful for other states in the Great Lakes region. -

Red-Banded Hairstreak Calycopis Cecrops (Fabricius 1793) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae)1 Donald W

EENY-108 Red-Banded Hairstreak Calycopis cecrops (Fabricius 1793) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae)1 Donald W. Hall and Jerry F. Butler2 Introduction The red-banded hairstreak, Calycopis cecrops (Fabricius), is a very attractive butterfly and one of our most common hairstreaks throughout the southeastern United States in dry open woods and wooded neighborhoods. Distribution The red-banded hairstreak is found from Maryland to southeast Kansas to eastern Texas and throughout Florida. As a stray, it is occasionally found as far north as southern Wisconsin and Minnesota. Figure 1. Adult red-banded hairstreak, Calycopis cecrops (Fabricius). Description Credits: Donald W. Hall, UF/IFAS Adults The wingspread of the adult is 24 to 30 mm (15/16–13/16 inches) (Opler and Malikul 1998). The under surface of the wings is gray-brown with a postmedial white line edged with a bright orange to red-orange band. Each hind wing has two tails (hairstreaks) with a relatively large conspicu- ous eyespot on the wing margin between the bases of the tails (Figure 1). Some spring specimens are darker in color (Field 1967) (Figure 2). Figure 2. Adult red-banded hairstreak, Calycopis cecrops (Fabricius), dark spring form. Credits: Donald W. Hall, UF/IFAS 1. This document is EENY-108, one of a series of the Entomology and Nematology Department, UF/IFAS Extension. Original publication date August 1999. Revised August 2010, August 2013, December 2016, and December 2019. Visit the EDIS website at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu for the currently supported version of this publication. This document is also available on the Featured Creatures website at http://entnemdept.ifas.ufl.edu/creatures/. -

Pine Island Ridge Management Plan

Pine Island Ridge Conservation Management Plan Broward County Parks and Recreation May 2020 Update of 1999 Management Plan Table of Contents A. General Information ..............................................................................................................3 B. Natural and Cultural Resources ...........................................................................................8 C. Use of the Property ..............................................................................................................13 D. Management Activities ........................................................................................................18 E. Works Cited ..........................................................................................................................29 List of Tables Table 1. Management Goals…………………………………………………………………21 Table 2. Estimated Costs……………………………………………………………….........27 List of Attachments Appendix A. Pine Island Ridge Lease 4005……………………………………………... A-1 Appendix B. Property Deeds………….............................................................................. B-1 Appendix C. Pine Island Ridge Improvements………………………………………….. C-1 Appendix D. Conservation Lands within 10 miles of Pine Island Ridge Park………….. D-1 Appendix E. 1948 Aerial Photograph……………………………………………………. E-1 Appendix F. Development Agreement………………………………………………….. F-1 Appendix G. Plant Species Observed at Pine Island Ridge……………………………… G-1 Appendix H. Wildlife Species Observed at Pine Island Ridge ……... …………………. H-1 Appendix -

St.Marks National Wildlife Refuge Butterfly Checklist

St.Marks National Wildlife Refuge Butterfly Checklist Assembled by Stacy Hurst, Richard G. RuBino, and Karla Brandt September 2002 Sponsored by the St. Marks Refuge Association, Inc. For more information on butterflies and other wildlife on the refuge, contact: St. Marks NationalWildlife Refuge 1255 Lighthouse Road, St. Marks, FL 32355 (850) 925-6121 http://saintmarks.fws.gov Sunset photo by Shawn Gillette, St. Marks NWR Inside photographs are reproduced by permission of Paul A. Opier l^ong-tailed Skipper (Urbanusproteus) - May-Nov; brushy or disturbed areas Silver-spotted Skipper (Epargyreus clarus) - Mar-Oct; open areas Milkweed Butterflies Monarch (Danaus plexippus) - Apr & Oct-Nov; open fields; clusters in trees ©Paul A. Opler ©Paul A Opler ©Paul A Opler ©Paul A. Opler Queen (Danaus gilippus) - Apr-Sep; open areas, brushy fields, roadsides Zebra Swallowtail Palamedes Swallowtail Gulf Fritillary American Lady Other Butterflies This checklist includes the most common species of butterflies found at St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge, the time of year they might be seen on the American Lady (Vanessa virginiensis) - Mar-May & Sep-Oct; open spaces refuge, and their habitat preferences. Carolina Satyr (Hermeuptychia sosybius) - Mar-Nov; open fields, wooded Swallowtails areas Black Swallowtail (Papilio polyxenes) - Jun-Nov; open fields, tidal Common Buckeye (Junonia coenia) - May-Nov; open fields, pine woods marshes Common Wood Nymph (Cercyonis pegala) -May-Sep; moist, grassy areas Eastern Tiger Swallowtail (Papilio glaucus) - Apr-Nov; edge of Common Buckeye deciduous woods Gemmed Satyr (Cyllopsis gemma) - May-Nov; moist grassy areas Giant Swallowtail (Papilio cresphontes) - Apr-Oct; woodlands and fields Georgia Satyr (Neonympha areolata) - Mar-Apr & Sep-Oct; open pine OPaul A. -

Arthropods of Elm Fork Preserve

Arthropods of Elm Fork Preserve Arthropods are characterized by having jointed limbs and exoskeletons. They include a diverse assortment of creatures: Insects, spiders, crustaceans (crayfish, crabs, pill bugs), centipedes and millipedes among others. Column Headings Scientific Name: The phenomenal diversity of arthropods, creates numerous difficulties in the determination of species. Positive identification is often achieved only by specialists using obscure monographs to ‘key out’ a species by examining microscopic differences in anatomy. For our purposes in this survey of the fauna, classification at a lower level of resolution still yields valuable information. For instance, knowing that ant lions belong to the Family, Myrmeleontidae, allows us to quickly look them up on the Internet and be confident we are not being fooled by a common name that may also apply to some other, unrelated something. With the Family name firmly in hand, we may explore the natural history of ant lions without needing to know exactly which species we are viewing. In some instances identification is only readily available at an even higher ranking such as Class. Millipedes are in the Class Diplopoda. There are many Orders (O) of millipedes and they are not easily differentiated so this entry is best left at the rank of Class. A great deal of taxonomic reorganization has been occurring lately with advances in DNA analysis pointing out underlying connections and differences that were previously unrealized. For this reason, all other rankings aside from Family, Genus and Species have been omitted from the interior of the tables since many of these ranks are in a state of flux. -

Butterflies and Moths of Comal County, Texas, United States

Heliothis ononis Flax Bollworm Moth Coptotriche aenea Blackberry Leafminer Argyresthia canadensis Apyrrothrix araxes Dull Firetip Phocides pigmalion Mangrove Skipper Phocides belus Belus Skipper Phocides palemon Guava Skipper Phocides urania Urania skipper Proteides mercurius Mercurial Skipper Epargyreus zestos Zestos Skipper Epargyreus clarus Silver-spotted Skipper Epargyreus spanna Hispaniolan Silverdrop Epargyreus exadeus Broken Silverdrop Polygonus leo Hammock Skipper Polygonus savigny Manuel's Skipper Chioides albofasciatus White-striped Longtail Chioides zilpa Zilpa Longtail Chioides ixion Hispaniolan Longtail Aguna asander Gold-spotted Aguna Aguna claxon Emerald Aguna Aguna metophis Tailed Aguna Typhedanus undulatus Mottled Longtail Typhedanus ampyx Gold-tufted Skipper Polythrix octomaculata Eight-spotted Longtail Polythrix mexicanus Mexican Longtail Polythrix asine Asine Longtail Polythrix caunus (Herrich-Schäffer, 1869) Zestusa dorus Short-tailed Skipper Codatractus carlos Carlos' Mottled-Skipper Codatractus alcaeus White-crescent Longtail Codatractus yucatanus Yucatan Mottled-Skipper Codatractus arizonensis Arizona Skipper Codatractus valeriana Valeriana Skipper Urbanus proteus Long-tailed Skipper Urbanus viterboana Bluish Longtail Urbanus belli Double-striped Longtail Urbanus pronus Pronus Longtail Urbanus esmeraldus Esmeralda Longtail Urbanus evona Turquoise Longtail Urbanus dorantes Dorantes Longtail Urbanus teleus Teleus Longtail Urbanus tanna Tanna Longtail Urbanus simplicius Plain Longtail Urbanus procne Brown Longtail