Standing Pharaoh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult

ΑΡΣΙΝΟΗ ΕΥΠΛΟΙΑ Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult Carlos Francis Robinson Bachelor of Arts (Hons. 1) A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2019 Historical and Philosophical Inquiry Abstract Queen Arsinoë II, the Maritime Aphrodite and Early Ptolemaic Ruler Cult By the early Hellenistic period a trend was emerging in which royal women were deified as Aphrodite. In a unique innovation, Queen Arsinoë II of Egypt (c. 316 – 270 BC) was deified as the maritime Aphrodite, and was associated with the cult titles Euploia, Akraia, and Galenaië. It was the important study of Robert (1966) which identified that the poets Posidippus and Callimachus were honouring Arsinoë II as the maritime Aphrodite. This thesis examines how this new third-century BC cult of ‘Arsinoë Aphrodite’ adopted aspects of Greek cults of the maritime Aphrodite, creating a new derivative cult. The main historical sources for this cult are the epigrams of Posidippus and Callimachus, including a relatively new epigram (Posidippus AB 39) published in 2001. This thesis demonstrates that the new cult of Arsinoë Aphrodite utilised existing traditions, such as: Aphrodite’s role as patron of fleets, the practice of dedications to Aphrodite by admirals, the use of invocations before sailing, and the practice of marine dedications such as shells. In this way the Ptolemies incorporated existing religious traditions into a new form of ruler cult. This study is the first attempt to trace the direct relationship between Ptolemaic ruler cult and existing traditions of the maritime Aphrodite, and deepens our understanding of the strategies of ruler cult adopted in the early Hellenistic period. -

Naukratis, Heracleion-Thonis and Alexandria

Originalveröffentlichung in: Damian Robinson, Andrew Wilson (Hg.), Alexandria and the North-Western Delta. Joint conference proceedings of Alexandria: City and Harbour (Oxford 2004) and The Trade and Topography of Egypt's North-West Delta, 8th century BC to 8th century AD (Berlin 2006), Oxford 2010, S. 15-24 2: Naukratis, Heracleion-Thonis and Alexandria - Remarks on the Presence and Trade Activities of Greeks in the North-West Delta from the Seventh Century BC to the End of the Fourth Century BC Stefan Pfeiffer The present article examines how Greek trade in Egypt 2. Greeks and SaTtic Egypt developed and the consequences that the Greek If we disregard the Minoan and Mycenaean contacts economic presence had on political and economic condi with Egypt, we can establish Greco-Egyptian relations as tions in Egypt. I will focus especially on the Delta region far back as the seventh century BC.2 A Greek presence and, as far as possible, on the city of Heracleion-Thonis on in the Delta can be established directly or indirectly for the Egyptian coast, discovered by Franck Goddio during the following places: Naukratis, Korn Firin, Sais, Athribis, underwater excavations at the end of the twentieth Bubastis, Mendes, Tell el-Mashkuta, Daphnai and century. The period discussed here was an exceedingly Magdolos. 3 In most of the reports, 4 Rhakotis, the settle exciting one for Egypt, as the country, forced by changes ment preceding Alexandria, is mentioned as the location in foreign policy, reversed its isolation from the rest of the of the Greeks, an assumption based on a misinterpreted ancient world. -

The Oriental Institute 2013–2014 Annual Report Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu The OrienTal insTiTuTe 2013–2014 annual repOrT oi.uchicago.edu © 2014 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2014. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago ISBN: 978-1-61491-025-1 Editor: Gil J. Stein Production facilitated by Editorial Assistants Muhammad Bah and Jalissa Barnslater-Hauck Cover illustration: Modern cylinder seal impression showing a presentation scene with the goddesses Ninishkun and Inana/Ishtar from cylinder seal OIM A27903. Stone. Akkadian period, ca. 2330–2150 bc. Purchased in New York, 1947. 4.2 × 2.5 cm The pages that divide the sections of this year’s report feature various cylinder and stamp seals and sealings from different places and periods. Printed by King Printing Company, Inc., Winfield, Illinois, U.S.A. Overleaf: Modern cylinder seal impression showing a presentation scene with the goddesses Ninishkun and Inana/Ishtar; and (above) black stone cylinder seal with modern impression. Akkadian period, ca. 2330–2150 bc. Purchased in New York, 1947. 4.2 × 2.5 cm. OIM A27903. D. 000133. Photos by Anna Ressman oi.uchicago.edu contents contents inTrOducTiOn introduction. Gil J. Stein........................................................... 5 research Project rePorts Achemenet. Jack Green and Matthew W. Stolper ............................................... 9 Ambroyi Village. Frina Babayan, Kathryn Franklin, and Tasha Vorderstrasse ....................... 12 Çadır Höyük. Gregory McMahon ........................................................... 22 Center for Ancient Middle Eastern Landscapes (CAMEL). Scott Branting ..................... 27 Chicago Demotic Dictionary (CDD). François Gaudard and Janet H. Johnson . 33 Chicago Hittite and Electronic Hittite Dictionary (CHD and eCHD). Theo van den Hout ....... 35 Eastern Badia. Yorke Rowan.............................................................. 37 Epigraphic Survey. W. Raymond Johnson .................................................. -

Islands in the Nile Sea: the Maritime Cultural Landscape of Thmuis, an Ancient Delta City

ISLANDS IN THE NILE SEA: THE MARITIME CULTURAL LANDSCAPE OF THMUIS, AN ANCIENT DELTA CITY A Thesis by VERONICA MARIE MORRISS Submitted to the Office of Graduate studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2012 Major Subject: Anthropology Islands in the Nile Sea: The Maritime Cultural Landscape of Thmuis, an Ancient Delta City Copyright 2012 Veronica Marie Morriss ISLANDS IN THE NILE SEA: THE MARITIME CULTURAL LANDSCAPE OF THMUIS, AN ANCIENT DELTA CITY A Thesis by VERONICA MARIE MORRISS Submitted to the Office of Graduate studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Approved by: Chair of Committee, Shelley Wachsmann Committee Members, Deborah Carlson Nancy Klein Head of Department, Cynthia Werner May 2012 Major Subject: Anthropology iii ABSTRACT Islands in the Nile Sea: The Maritime Cultural Landscape of Thmuis, an Ancient Delta City. (May 2012) Veronica Marie Morriss, B.A., The Pennsylvania State University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Shelley Wachsmann In ancient Egypt, the Nile was both a lifeline and a highway. In addition to its crucial role for agriculture and water resources, the river united an area nearly five hundred miles in length. It was an avenue for asserting imperial authority over the vast expanse of the Nile valley. River transport along the inland waterways was also an integral aspect of daily life and was employed by virtually every class of society; the king and his officials had ships for commuting, as did the landowner for shipping grain, and the ‘marsh men’ who lived in the northernmost regions of the Nile Delta. -

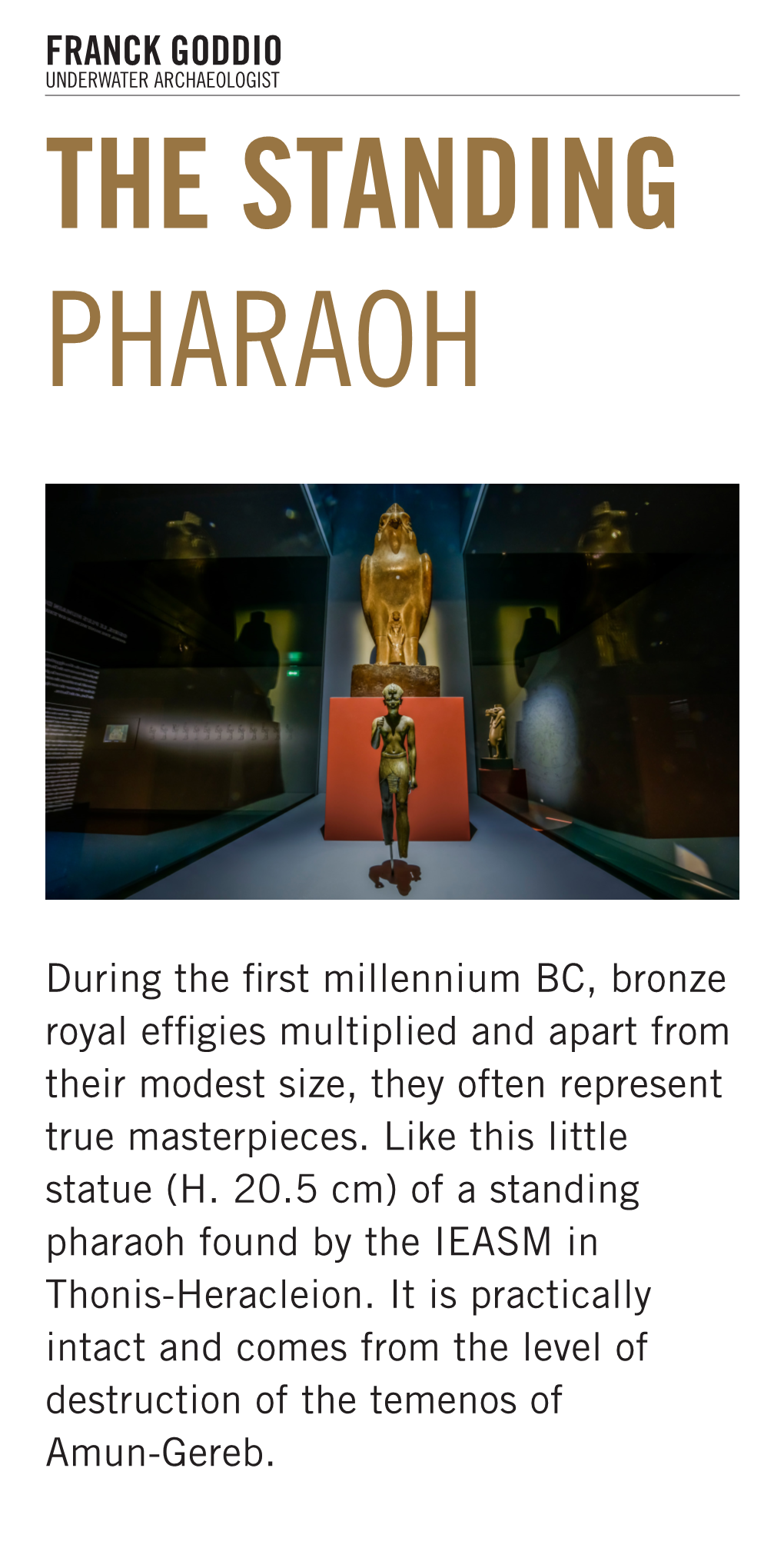

Soaked in History Positioned Throughout the Exhibition Shows Divers Investigating and Rescuing a Few Key Objects, Including a Sycamore Barge of Osiris

Sunken Cities: operation by the Egypt’s Lost European Institute for Worlds Underwater Archaeol- British Museum, ogy (IEASM) in Paris, London. Until 27 November directed by Franck 2016. Goddio. The team used side-scan sonar, nuclear magnetic resonance magnetometers and sub-bottom profilers to reveal slices through the geological strata beneath the sea bed, allowing them to begin partial excava- tion. Divers uncovered buildings, massive sculptures and a huge range of objects, from bronze incense burners to gold jewellery. GERIGK FOUNDATION/CHRISTOPH FRANCK GODDIO/HILTI More than 750 ancient anchors and 69 ships were also detected in the ooze, most of them from the sixth to second centuries bc, in Thonis-Heracleion’s harbour. An exhibition of this extraordinary trove, Sunken Cities, is the first large-scale show of underwater discoveries at the British Museum in London, and the most complete presentation of this complex Egyptian– Greek society so far. More than 200 IEASM finds are exhibited, denoted on the information panels by a hier- oglyphic zigzag symbolizing water. Many of them were displayed in Berlin’s Martin- Gropius-Bau and the Grand Palais in Paris in 2006–07, but much has been discovered since. Among the stone statues of deities and rulers in pharaonic or Greek dress is a 5.4- metre figure of Hapy, god of the Nile inunda- tion, which greets visitors as it once greeted Greek sailors approaching the mouth of the Nile. Nearby are inscriptions in hieroglyphic and Greek on stone and gold, intricate jewel- lery in recognizably Greek styles and deli- cate lead models of votive barques used in the cult of Osiris. -

6. a Note on the Navigation Space of the Baris-Type Ships from Thonis-Heracleion

E Sailing from Polis to Empire MMANUEL Ships in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Hellenistic Period N ANTET EDITED BY EMMANUEL NANTET WITH A PREFACE BY ALAIN BRESSON ( ED Sailing from Polis to Empire What can the architecture of ancient ships tell us about their capacity to carry cargo or to .) navigate certain trade routes? How do such insights inform our knowledge of the ancient S economies that depended on mari� me trade across the Mediterranean? These and similar ques� ons lie behind Sailing from Polis to Empire, a fascina� ng insight into the prac� cali� es of trading by boat in the ancient world. Allying modern scien� fi c knowledge with Hellenis� c sources, this interdisciplinary collec� on brings together experts in various fi elds of ship archaeology to shed new light on the role played by ships and AILING sailing in the exchange networks of the Mediterranean. Covering all parts of the Eastern Mediterranean, these outstanding contribu� ons delve into a broad array of data – literary, epigraphical, papyrological, iconographic and archaeological – to understand the trade FROM routes that connected the economies of individual ci� es and kingdoms. Unique in its interdisciplinary approach and focus on the Hellenis� c period, this collec� on P digs into the ques� ons that others don’t think to ask, and comes up with (some� mes OLIS surprising) answers. It will be of value to researchers in the fi elds of naval architecture, Classical and Hellenis� c history, social history and ancient geography, and to all those with TO an interest in the ancient world or the seafaring life. -

The Oriental Institute 2012–2013 Annual Report

http://oi.uchicago.edu The OrienTal insTiTuTe 2012–2013 annual repOrT The OrienTal insTiTuTe 2012–2013 annual repOrT http://oi.uchicago.edu © 2013 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2013. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago ISBN-13: 978-1-61491-016-9 ISBN-10: 1614910162 Editor: Gil J. Stein Cover and title page illustration: “Birds in an Acacia Tree.” Nina de Garis Davies, 1932. Tempera on paper. 46.36 × 55.90 cm. Collection of the Oriental Institute. Oriental Institute digital image D. 17882. Between Heaven & Earth Catalog No. 11. The pages that divide the sections of this year’s report feature images from last year’s special exhibit Between Heaven & Earth: Birds in Ancient Egypt. Printed through Four Colour Print Group, by Lifetouch, Loves Park, Illinois The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Services — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. ∞ http://oi.uchicago.edu contents contents introduction Introduction. Gil J. Stein ................................................................. 7 In Memoriam ........................................................................... 9 research Project Reports ...................................................................... 15 Archaeology of Islamic Cities. Donald Whitcomb........................................... 15 Center for Ancient Middle Eastern Landscapes (CAMEL). Scott Branting ..................... 18 Chicago Demotic -

The Decree of Saïs

Underwater Egypt in Region Canopic the in Archaeology OCMA Underwater Archaeology in the Canopic Region in Egypt The Decree of Saïs The Decree of Saïs of Decree The The cover illustrations show the perfectly preserved stele of Thonis-Heracleion, intact after having spent over 1000 years at the bottom of the sea. It is the second known stele containing the text of the decree promulgated by Nectanebo I,founder of the thirtieth dynasty, and announces a permanent donation to the goddess Neith, ‘Mistress of the Floods’, out of the customs dues received in the town of Thonis- Heracleion and out of the taxes on Greek trade in the town of Naukratis. ISBN 978-1-905905-23-2 Published by the Oxford Centre for Maritime Archaeology at the School of Archaeology, University of Oxford Anne-Sophie von Bomhard The Decree of Saïs The Stelae of Thonis-Heracleion and Naukratis Oxford Centre for Maritime Archaeology Monograph Series Series editors: Franck Goddio and Damian Robinson 1 Topography and Excavation of Heracleion-Thonis and East Canopus (1996–2006) by Franck Goddio 2 Geoarchaeology by Jean-Daniel Stanley et al 3 The Naos of the Decades by Anne-Sophie von Bomhard 4 La stèle de Ptolémée VIII Évergète II à Héracléion by Christophe Thiers 5 Alexandria and the North-Western Delta edited by Damian Robinson and Andrew Wilson 6 Maritime Archaeology and Ancient Trade in the Mediterranean edited by Damian Robinson and Andrew Wilson The Underwater Archaeology of the Canopic Region in Egypt The Decree of Saïs The Stelae of Thonis-Heracleion and Naukratis by Anne-Sophie von Bomhard Oxford Centre for Maritime Archaeology: Monograph 7 School of Archaeology, University of Oxford 2012 All rights reserved. -

'Egypt's Sunken Cities' at the Minneapolis Institute of Art Showcases

PRESS RELEASE ‘Egypt’s Sunken Cities’ at the Minneapolis Institute of Art showcases more than 250 antiquities from one of history’s most significant underwater archaeological finds The exhibition unearths the rich history of two cities that were submerged in the Mediterranean Sea for more than 1,000 years An archaeologist inspects the still-encrusted head of a statue of a queen on site underwater in Thonis- Heracleion, Ptolemaic period (332-30 BC); granodiorite; height: 86 5/8 inches; National Museum of Alexandria (SCA 283); IEASM Excavations; Photo: Christoph Gerigk © Franck 2400 Third Avenue South Goddio / Hilti Foundation Minneapolis, MN 55404 artsmia.org MINNEAPOLIS—August 14, 2018—This fall, the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia) will show an exhibition of antiquities from one of the greatest finds in the history of underwater archaeology. “Egypt’s Sunken Cities,” presented by U.S. Bank, will feature colossal, 16-foot-tall sculptures and precious artifacts from the long-lost cities of Thonis-Heracleion and Canopus. The exhibition will focus on the discoveries made during more than 20 years of underwater excavation by French archaeologist Franck Goddio and the European Institute for Underwater Archaeology. The exhibition opens November 4, 2018, and is on view for an extended six-month run through April 14, 2019. It was recently shown at the Museum Rietberg in Zurich, the British Museum in London, the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, and the Saint Louis Art Museum. "Mia is thrilled to bring this exciting exhibition to the Twin Cities," said Jan-Lodewijk Grootaers, curator of African art and head of Mia’s Department of Arts of Africa and the Americas. -

Sunken Cities: Egypt's Lost Worlds Audio Guide Transcript

Audio Guide Transcript Sunken Cities: Egypt’s Lost Worlds March 25–September 9, 2018 Main Exhibition Galleries Introduction to Sunken Cities: Egypt’s Lost Worlds Speaker: Brent Benjamin Barbara B. Taylor Director Saint Louis Art Museum Hello, I’m Brent Benjamin, The Barbara B. Taylor Director of the Saint Louis Art Museum. I’d like to welcome you to our exhibition Sunken Cities: Egypt’s Lost Worlds. Many of the objects you are about to see were lost for more than 1,200 years under the waters of the Mediterranean Sea. In 1996, the European Institute of Underwater Archaeology initiated a search for two cities, whose histories were only known through ancient accounts. The research team, led by underwater archaeologist Franck Goddio, has since discovered a variety of incredible objects from these underwater excavations and confirmed the two cities’ names: Thonis-Heracleion and Canopus. In this exhibition you will find exceptionally preserved artifacts, which offer us a better understanding of life in Egypt in the first millennium. The Museum’s presentation is the first time many of these works of art will be seen in the United States. The recently discovered colossal statues, votive offerings, and jewelry are also supplemented by works of art from museums across Egypt. These treasures help tell the story of cities and cultures that flourished together in the ancient world. Your journey begins in the 7th century BC in the ancient Egyptian port of Thonis-Heracleion. As you continue through the exhibition, you will learn about the religious customs of the city. Subsequent galleries will highlight Osiris, the Egyptian god of underworld, whose family and legend shaped the Mysteries of Osiris, one of the most important ceremonies celebrated throughout ancient Egypt. -

UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology

UCLA UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology Title Late Dynastic Period Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2zg136m8 Journal UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 1(1) Author Ladynin, Ivan Publication Date 2013-08-20 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California LATE DYNASTIC PERIOD العصر المتأخر Ivan Ladynin EDITORS WILLEKE WENDRICH Editor-in-Chief University of California, Los Angeles JACCO DIELEMAN Editor University of California, Los Angeles ELIZABETH FROOD Editor University of Oxford WOLFRAM GRAJETZKI Area Editor Time and History University College London JOHN BAINES Senior Editorial Consultant University of Oxford Short Citation: Ladynin, 2013, Late Dynastic Period. UEE. Full Citation: Ladynin, Ivan, 2013, Late Dynastic Period. In Wolfram Grajetzki and Willeke Wendrich (eds.), UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, Los Angeles. http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz002hd59r 8502 Version 1, August 2013 http://digital2.library.ucla.edu/viewItem.do?ark=21198/zz002hd59r LATE DYNASTIC PERIOD العصر المتأخر Ivan Ladynin Spätdynastische Zeit Époque tardive The Late Dynastic Period is the last period of Egyptian independence under Dynasties 28 to 30 (404 - 343 BCE). As for Egypt’s position in the world, this was the time their military and diplomatic efforts focused on preventing reconquest by the Persian Empire. At home, Dynasties 28 - 29 were marked by a frequent shift of rulers, whose reigns often started and ended violently; in comparison, Dynasty 30 was a strong house, the rule of which was interrupted only from the outside. Culturally this period saw the continuation of certain Late Egyptian trends (archaistic tendency, popularity of animal cults, cult of Osiris and divine couples), which became the platform for the evolution of the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods. -

Ram of Amun Limestone Slab

FRANCK GODDIO UNDERWATER ARCHAEOLOGIST RAM OF AMUN LIMESTONE SLAB During the IEASM excavations of a small sanctuary in an area north of the temple of Amun-Gereb in Thonis- Heracleion a limestone slab was discovered with two finely chiselled ram’s heads figure on both sides. They are no doubt the representation of Amun. Cult of Nubian origins Horns and ears identify him as ovis aries palaeoatlanticus, a species which appeared in Egypt around 2000 BC, perhaps coming from Nubia, which was conquered during the New Kingdom, and where the population was intensely engaged in the rearing of livestock. The Nubian origins of this cult could explain the association of the ram with Amun, and thus the addition of curved horns to the crowns of the reigning or the de- ceased king on the occasion of specific rituals represented in the Osiris temple at Abydos. Continous use of ram motif The use of this motif of the ram’s head with curved horns was continued into the Ptolemaic and Roman periods. On coins, these curved ram’s horns of the king of the gods flanked the head of Alexander the Great, who was recognised by the oracle at the temple of Siwa (“the oasis of Amun”) as the son of Zeus (Amun). According to Callisthenos, the divine decision was rendered by a sign of the “face of Amun” set at the bow of the sacred barge. Was it a ram’s head like that which decorated the boat of the god at Thebes? Whatever it was, this affiliation appeared differently several centuries later.