Cassava Value Chains and Livelihoods in South-East Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yangon University of Economics Department of Commerce Master of Banking and Finance Programme

YANGON UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE MASTER OF BANKING AND FINANCE PROGRAMME INFLUENCING FACTORS ON FARM PERFORMANCE (CASE STUDY IN BOGALE TOWNSHIP, AYEYARWADY DIVISION) KHET KHET MYAT NWAY (MBF 4th BATCH – 30) DECEMBER 2018 INFLUENCING FACTORS ON FARM PERFORMANCE CASE STUDY IN BOGALE TOWNSHIP, AYEYARWADY DIVISION A thesis summited as a partial fulfillment towards the requirements for the Degree of Master of Banking and Finance (MBF) Supervised By : Submitted By: Dr. Daw Tin Tin Htwe Ma Khet Khet Myat Nway Professor MBF (4th Batch) - 30 Department of Commerce Master of Banking and Finance Yangon University of Economics Yangon University of Economics ABSTRACT This study aims to identify the influencing factors on farms’ performance in Bogale Township. This research used both primary and secondary data. The primary data were collected by interviewing with farmers from 5 groups of villages. The sample size includes 150 farmers (6% of the total farmers of each village). Survey was conducted by using structured questionnaires. Descriptive analysis and linear regression methods are used. According to the farmer survey, the household size of the respondent is from 2 to 8 members. Average numbers of farmers are 2 farmers. Duration of farming experience is from 11 to 20 years and their main source of earning is farming. Their living standard is above average level possessing own home, motorcycle and almost they owned farmland and cows. The cultivated acre is 30 acres maximum and 1 acre minimum. Average paddy yield per acre is around about 60 bushels per acre for rainy season and 100 bushels per acre for summer season. -

Myanmar: GLIDE N° TC-2008-000057-MMR Operations Update N° 31 Cyclone Nargis 1 May 2011

Emergency appeal n° MDRMM002 Myanmar: GLIDE n° TC-2008-000057-MMR Operations update n° 31 Cyclone Nargis 1 May 2011 THIRD YEAR REPORT This report consists of an overview of the third year of operations. For specific operational and programmatic details, please see Operations Update No.30 issued in March. Period covered by this update: May 2010 to April 2011 Appeal target: CHF 68.5 million1 Appeal coverage: 103% <view attached financial report, updated donor response report, or contact details> The household shelter project benefited a total of 12,404 families up to the end of March this year. In this photo, an elderly beneficiary stands outside his new home in Hpaung Yoe Seik village in Kyaiklat township. (Photo: Myanmar Red Cross Society) 1 The budget was revised down to CHF 68.5 million in March and accordingly, the revised appeal was extended by two months from May to end July 2011. This was indicated in Operations Update No 30 issued on 2 March 2011. Appeal history: • 2 March 2011: The budget was revised down to CHF 68.5 million and the revised appeal extended by two months from May to end-July 2011. A final report will be made available by end-October. Field activities, however, will remain largely unaffected and are scheduled to conclude by early May, as per the emergency appeal of 8 July 2008. • 8 July 2008: A revised emergency appeal was launched for CHF 73.9 million to assist 100,000 households for 36 months. • 16 May 2008: An emergency appeal was launched for CHF 52,857,809 to assist 100,000 households for 36 months. -

Report Administration of Burma

REPORT ON THE ADMINISTRATION OF BURMA FOR THE YEAR 1933=34 RANGOON SUPDT., GOVT. PRINTING AND STATIONERY, BURMA 1935 LIST OF AGENTS FOR THE SALE~OF GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN BURMA. AllERICAN BAPTIST llIISSION PRESS, Rangoon. BISWAS & Co., 226 Lewis Street, Rangoon. BRITISH BURMA PRESS BRANCH, Rangoon .. ·BURMA BOO!, CLUB, LTD., Poat Box No. 1068, Rangoon. - NEW LIGHT 01' BURlL\ Pl?ESS, 61 Sule Pagoda Road, Rangoon. PROPRIETOR, THU DHA!IIA \VADI PRE,S, 16-80 lliaun!l :m,ine Street. Rangoon. RANGOOX TIMES PRESS, Rangoon. THE CITY BOOK CLUB, 98 Phayre Street, Rangoon . l\IESSRS, K. BIN HOON & Soi.:s, Nyaunglebin. MAUNG Lu GALE, Law Book Depot, 42 Ayo-o-gale. Manrlalay. ·CONTINENTAL TR.-\DDiG co.. No. 353 Lower Main Road. ~Ioulmein. lN INDIA. BOOK Co., Ltd., 4/4A College Sq<1are, Calcutta. BUTTERWORTH & Co. Undlal, "Ltd., Calcutta . .s. K. LAHIRI & Co., 56 College Street, Calcutta. ,v. NEWMAN & Co., Calcutta. THACKER, SPI:-K & Co., Calcutta, and Simla. D. B. TARAPOREVALA, Soxs & Co., Bombay. THACKER & Co., LTD., Bombay. CITY BOO!! Co., Post Box No. 283, l\Iadras. H!GGINBOTH.UI:& Co., Madras. ·111R. RA~I NARAIN LAL, Proprietor, National1Press, Katra.:Allahabad. "MESSRS. SAllPSON WILL!A!II & Co., Cawnpore, United Provinces, IN }j:URUPE .-I.ND AMERICA, -·xhc publications are obtainable either ~direct from THE HIGH COMMISS!Oli:ER FOR INDIA, Public Department, India House Aldwych, London, \V.C. 2, or through any bookseller. TABLE OF CONTENTS. :REPORT ON THE ADMINISTRATION OF BURMA FOR THE YEAR 1933-34. Part 1.-General Summary. Part 11.-Departmental Chapters. CHAPTER !.-PHYSICAL AND POLITICAT. GEOGRAPHY. "PHYSICAL-- POLITICAL-co11clcl. -

Pyapon Hub Update No 2 FINAL

UNITED NATIONS OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS Myanmar Cyclone Nargis Pyapon Hub Update No. 2 13 November 2008 (Reporting period 23 October - 12 November 2008) OVERVIEW & KEY DEVELOPMENTS · The Prime Minister of the Union of Myanmar, General Thein Sein, visited Pyapon on 28 October 2008. He held a meeting with all township stakeholders and received a briefing on the progress on the Nargis response from General Soe Naing, the Minister of Hotel and Tourism. Rehabilitation and reconstruction activities include housing, schools, religious buildings, the Pyapon-Kyon Ka Dun -Ah Mar road, cyclone shelters and paddy fields. The Minister encouraged people to work hard in order to modernise the agricultural sector. He donated 6 million Kyat to the District Medical Officer (DMO) for the renovation of Pyapon District Hospital which has since been upgraded from 100 beds to 200 beds. · At the seventh General Coordination Meeting on 30 October in Pyapon, the ATEO (Assistant Township Education Officer) highlighted the important issues to be aware of when renovating schools, as well as the need for first aid kits and first aid training in schools. He also briefed about the Natural Disaster Reduction Management Course. The TPDC Chairman has identified school reconstruction as the major need in Maubin. · On 1 November, Mingalar Myanmar donated 200 fishing boats and 200 fishing nets to beneficiaries from 17 villages in Dedaye and Pyapon Townships. The Minister of Hotel and Tourism, who is responsible for cyclone response in Pyapon, Dedaye and Kyaiklat Townships, presided the ceremony, which was attended by local officials, the Ambassador of Singapore and private donors from Singapore and held in Sar Oh Chaung village of Ohn Pin Village Tract, Dedaye To wnship. -

Hazard Profile of Myanmar: an Introduction 1.1

Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................ I List of Figures ................................................................................................................ III List of Tables ................................................................................................................. IV Acronyms and Abbreviations ......................................................................................... V 1. Hazard Profile of Myanmar: An Introduction 1.1. Background ...................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Myanmar Overview ......................................................................................................... 2 1.3. Development of Hazard Profile of Myanmar : Process ................................................... 2 1.4. Objectives and scope ....................................................................................................... 3 1.5. Structure of ‘Hazard Profile of Myanmar’ Report ........................................................... 3 1.6. Limitations ....................................................................................................................... 4 2. Cyclones 2.1. Causes and Characteristics of Cyclones in the Bay of Bengal .......................................... 5 2.2. Frequency and Impact .................................................................................................... -

47086-002: Maubin-Phyapon Road Rehabilitation Project

Social Safeguards Monitoring Report Semi-Annual Report (January to June 2018) December 2018 MYA: Maubin-Phyapon Road Rehabilitation Project Prepared by the Project Management Unit, Ministry of Construction for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 1 December 2018) Currency unit – kyat (K) K1.00 = $0.00063 $1.00 = K1,598 NOTE In this report, "$" refers to US dollars unless otherwise stated. This social safeguards monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. 1 Semi-Annual Social Safeguard Monitoring Report June 2018 Semi-Annual Report) (January 2018 – June 2018) MYA: Maubin – Pyapon Road Rehabilitation Project (ADB Loan No. 3199 (MYA) 2 Prepared by Ministry of Construction (MOC) – Project Management Unit (PMU) for the Asian Development Bank. This semi-annual social safeguard monitoring report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. -

Burma. Gazetteer Henzada District

BURMA. GAZETTEER HENZADA DISTRICT VOLUME A COMPILED BY MR. W. S. MORRISON, I.C.S. (ASSISTANT COMMISSIONER), SETTLEMENT OFFICER SUPERINTENDENT, GOVERNMENT PRINTING AND STATIONERY, RANGOON. LIST OF AGENTS FROM WHOM GOVERNMENT OF BURMA PUBLICATIONS ARE AVAILABLE IN BURMA 1. CITY BOOK CLUB, 98, Phayre Street, Rangoon. 2. PROPRIETOR, THU-DHAMA-WADI PRESS, 55-56, Tees Kai Maung Khine Street, Rangoon. 3. PROPRIETOR, BURMA NEWS AGENCY, 135, Anawrahta Street, Rangoon. 4. MANAGER, UNION PUBLISHING HOUSE, 94, "C" Block, Bogyoke Market, Rangoon. 5. THE SECRETARY, PEOPLE'S LITERATURS COMMITTEE AND HOUSE, 546, Merchant Street, Rangoon, 6. THE BURMA TRANSLATION SOCIETY, 520, Merchant Street, Rangoon. 7. MESSERS. K. BIN HOON & SONS, Nyaunglebin, Pegu District. 8. U LU GALE, GOVERNMENT LAW BOOK AGENT, 34th Road, Nyaungzindan Quarter, Mandalay. 9. THE NATIONAL BOOK DEPOT AND STATIONERY SUPPLY HOUSE, North Godown, Zegyo, Mandalay. 10. KNOWLEDGE BOOK HOUSE, 130, Bogyoke Street, Rangoon. 11. AVA HOUSE, 232, Sule Pagoda Road, Rangoon. 12. S.K. DEY, BOOK SUPPLIER & NEWS AGENTS (In Strand Hotel), 92, Strand Road, Rangoon. 13. AGAWALL BOOKSHOP, Lanmadaw, Myitkyina. 14. SHWE OU DAUNG STORES, BOOK SELLERS & STATIONERS, No. 267, South Bogyoke Road, Moulmein. 15. U AUNG TIN, YOUTH STATIONERY STORES, Main Road, Thaton. 16. U MAUNG GYI, AUNG BROTHER BOOK STALL, Minmu Road, Monywa. 17. SHWSHINTHA STORES, Bogyoke Road, Lashio, N.S.S. 18. L. C. BARUA, PROPRIETOR, NATIONAL STORES, No. 16-17, Zegyaung Road, Basein. 19. DAW AYE KYI, No. 42-44 (in Bazaar) Book Stall, Maungmya. 20. DOBAMA U THEIN, PROPRIETOR, DOBAMA BOOK STALL, No. 6, Bogyoke Street, Henzada. 21. SMART AND MOOKERDUM, No. -

Development of a Delft3d Model for the Ayeyarwady Delta, Myanmar Part II: Data Acquisition and Model Validation

TU DELFT & DELTARES Development of a Delft3D model for the Ayeyarwady delta, Myanmar Part II: Data acquisition and model validation Erik Hendriks 19-Mar-16 1 Disclaimer The contents of this report are the result of a cooperation between Deltares, Delft University of Technology and the Myanmar Ministry of Transport. No part of this report may be reproduced, published, distributed, displayed, performed, copied or stored for public or private use in any information retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any mechanical, photographic or electronic process, including electronically or digitally on the Internet or World Wide Web, or over any network, or local area network, without written permission of Deltares and the author. © Stichting Deltares 2016, all rights reserved. 2 Abstract This report presents the development of a Delft3D model for the water system in the Ayeyarwady delta, located in the south of Myanmar. Problems in this delta are flooding and salt intrusion into the rivers and delta of Myanmar. Understanding these phenomena is important since floods affect the safety of the people and salt intrusion impacts the quality of irrigation and drinking water. The main objective of this project is to develop a Delft3D model that can serve as a starting point for modelling these processes. This report will present the development of a 2D tidal model and validation of this model with locally measured data. Also, some preliminary results will be presented for 3D salt intrusion computations. This report is the second part of the development of a Delft3D model. It is an addition to the work by Attema (2013), who developed the initial Delft3D model for the Ayeyarwady delta. -

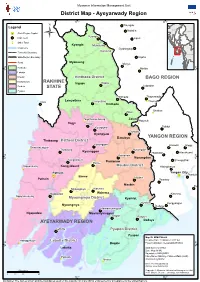

Ayeyarwady Region

Myanmar Information Management Unit District Map - Ayeyarwady Region 95° E 96° E Paungde Legend INDIA Nattalin CHINA .! State/Region Capital Kyangin Main Town Ü Zigon !( Other Town Kyangin Myanaung Coast Line !( Gyobingauk Kanaung Township Boundary THAILAND State/Region Boundary Okpho Road Myanaung Monyo N Kyeintali N ° Hinthada !( ° 8 Minhla 8 1 1 Labutta Maubin Hinthada District BAGO REGION Myaungmya RAKHINE Ingapu Ingapu Pathein STATE Letpadan Pyapon Hinthada Thayarwady Gwa Lemyethna Lemyethna !( Thonse Hinthada Okekan Zalun !( Ngathaingchaung Zalun !( Ahpyauk !( Yegyi Yegyi Kyonpyaw Taikkyi Danubyu Kyonpyaw Danubyu YANGON REGION Thabaung Pathein District Kyaunggon Hmawbi Hlegu Shwethaungyan !( Thabaung Nyaungdon Kyaunggon Htantabin Htaukkyant N N ° Pantanaw ° 7 7 1 Nyaungdon 1 Kangyidaunt Pantanaw Shwepyithar Einme Ngwesaung Kangyidaunt Maubin District !( Hlaingtharya Pathein Yangon City .! .! Thanlyin Einme Maubin Pathein Twantay Maubin Kyauktan Myaungmya Wakema Ngapudaw Wakema Kawhmu Ngayokekaung !( Myaungmya District Kyaiklat Kyaiklat Kungyangon Myaungmya Dedaye Mawlamyinegyun Ngapudaw Mawlamyinegyun Bogale Pyapon AYEYARWADY REGION Dedaye Labutta Pyapon District Pyapon Map ID: MIMU764v04 Hainggyikyun Creation Date: 23 October 2017.A4 N Labutta District N !( ° Bogale Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 ° 6 6 1 1 Labutta Data Sources: MIMU Base Map: MIMU Boundaries: MIMU/WFP Pyinsalu Place Name: Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) !( Ahmar translated by MIMU !( Email: [email protected] Website: www.themimu.info Kilometers Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit 2017. May be used free of charge with attribution. 0 10 20 40 95° E 96° E Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.. -

Land Settlement Reports Burma Akyab District. Amherst District

Land Settlement Reports Burma Akyab District. MF-3960 reel 140. Report on the settlement operations in the Akyab District, season 1886-87 [microform]. Rangoon : Printed by the Superintendent, Govt. Printing, 1888. V/27/314/223 OCLC # 24160149 MF-3960 reel 141. Report on the settlement operations in the Akyab District, season 1887-88 [microform]. Rangoon : Printed by the Superintendent, Govt. Printing, 1888. V/27/314/224 OCLC # 24161496 MF-3981 reel 31. Report on the revision settlement operations in the Akyab District, season 1901-1902. [microform]. Rangoon : Printed at British Burma Press, 1903. V/27/314/225 OCLC # 24204343. MF-3981 reel 32. Report on the revision settlement operations in the Akyab District, season 1902-1903. [microform]. Rangoon : Printed at the British Burma Press, 1903. V/27/314/226 OCLC # 24204365 MF-3981 reel 33. Report on the summary settlement of three cadastrally surveyed circles in the Akyab District, season 1903-04 [microform] : accompanied by map and four appendices. Rangoon : Office of Superintendent Govt. Printing, 1905. V/27/314/227 OCLC # 24204378 MF-15057 r.1 Report on the revision settlement operations in the Akyab district, season 1913-17. / Smart, Robert Baddington. Rangoon : Office of the Superintendent, Government Printing, Burma, 1918. Contents : 1, General description of the settlement area.--2, The people.--3, Agricultural.--4, Occupancy.--5, The expiring settlement.--6, The new settlement.--7, Miscellaneous remarks and suggestions.--Appendices.--Maps.; Includes notes, resolution and V (9) 4128 = V/27/314/228 OCLC # 85774574 Amherst District. MF-3981 reel 34. Report on the settlement operations in the Amherst District, season 1891-92. -

Myanmar Insurance State / Division and Districts Address No Branches

Myanmar Insurance State / Division And Districts Address No Branches Address 1 Kachin State U Paing No.(26/1), Ayeyar Quarter, Ayemarnwe La Payar Kyaung Lane And Construction Between Myikyine 2 Kayah State Akwet No.(18), Daweukhu Quarter, Daweukhu (6) Lane, Loikaw 3 Kayin State No.(5) Quarter, Bogyoke Lane, HPA-AN 4 Chin State U Paing No (100), Bogyoke Lane And Methatgon Tat Lane, Harkha, Kwin No. 4, Myaekwet No. 4, Myoe Thit Quarter, Bogyoke Lane 5 Mon State Mg Ngan Quarter, Taung Waing Lane And Taung Paw Lane Corner, Mawlamyine 6 Rakhine State May Yu Lane, Ma Kyine Myaing Quarter, Near Miesat Gyi, Sittwe 7 Shan State Bogyoke Aung San Lane, Thit Taw Quarter Taunggyi 8 Sagaing Division 11/2 Kan Tha Yar Park Lane (West), Yone Gyi Quarter, Monywar 9 Tanintharyi Division No.(38), Sayon Lane, Mhaw Ein (West) Kwet Nyaung Yan Taung Quarter, Dawei 10 Bago Division No.(211), 33 Lane, Shinsawpu Quarter, Bago 11 Magwe Division Ah Kwet No(1), (14) Lane, Kanthayar Quarter, Magwe 12 Mandalay Division No.(414), 63 Lane,34x35 Between, Pyigyimyatshin Quarter, Chan Aye Tha Zan Township, Mandalay 13 Aye Yar Wady Shwe Wuthmone Park Lane, Shwe Wuthmone Yet, Division (13) Quarter, Pathein 14 Naypyitaw Division No(964/965),22 Lane And Myintzu Lane Corner Aung Tha Yar Quarter, Pokepathiyi Township, Naypyitaw 15 Kyaington District Myo Thit Yet, (3) Quarter, Myotaw Khan Ma (West), Kyaington 16 Kyaukse District Kyatminton Quarter, Su Pound Yongyi (West), Kyaukse No Branches Address 17 Kale District Bog Yoke Lane, Nyaung Tha Yar Quarter (Siman Khan Khwemu Comity Yan Township), Kale 18 Sagaing District 80 (D) Thiyi Mingala Lane, Payami Quarter Sagaing 19 Tarchileik District Haung Laik Quarter, Satmhu Lane, Tarchileik 20 Taungoo District Siman Kain Yon District (South), 9 Quarter, Oak Kyutan, Yangon-Mandalay Lane, Taungoo 21 Pyay District Khi Taryar Myothit (8) Lane , BA Yint Naung Lane Magyi, Pyay 22 Pakokku District No. -

List of Districts of Burma

State/ Region Name of District Central Burma Magway Region Gangaw District Central Burma Magway Region Magway District Central Burma Magway Region Minbu District Central Burma Magway Region Pakokku District Central Burma Magway Region Thayet District Central Burma Mandalay Region Kyaukse District Central Burma Mandalay Region Mandalay District Central Burma Mandalay Region Meiktila District Central Burma Mandalay Region Myingyan District Central Burma Mandalay Region Nyaung-U District Central Burma Mandalay Region Pyin Oo Lwin District Central Burma Mandalay Region Yamethin District Central Burma Naypyidaw Union Territory Naypyitaw District East Burma Kayah State Bawlakhe District East Burma Kayah State Loikaw District East Burma East Shan State Kengtong District East Burma East Shan State Mongsat District East Burma East Shan State Mong Hpayak District East Burma East Shan State Techilelk District East Burma North Shan State Kunlong District East Burma North Shan State Kyaukme District East Burma North Shan State Laukkaing District East Burma North Shan State Lashio District East Burma North Shan State Muse District East Burma North Shan State Hopang District (created on Sept. 2011) East Burma North Shan State Metman District East Burma North Shan State Mongmit District East Burma South Shan State Langkho District East Burma South Shan State Loilen District East Burma South Shan State Taunggyi District Lower Burma Ayeyarwady Region Hinthada District Lower Burma Ayeyarwady Region Labutta District Lower Burma Ayeyarwady Region Maubin District