4:30 P. M. Thursday 16 April 1936 Yaleuniversity We Are Gathered

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Timeline of Women at Yale Helen Robertson Gage Becomes the first Woman to Graduate with a Master’S Degree in Public Health

1905 Florence Bingham Kinne in the Pathology Department, becomes the first female instructor at Yale. 1910 First Honorary Degree awarded to a woman, Jane Addams, the developer of the settlement house movement in America and head of Chicago’s Hull House. 1916 Women are admitted to the Yale School of Medicine. Four years later, Louise Whitman Farnam receives the first medical degree awarded to a woman: she graduates with honors, wins the prize for the highest rank in examinations, and is selected as YSM commencement speaker. 1919 A Timeline of Women at Yale Helen Robertson Gage becomes the first woman to graduate with a Master’s degree in Public Health. SEPTEMBER 1773 1920 At graduation, Nathan Hale wins the “forensic debate” Women are first hired in the college dining halls. on the subject of “Whether the Education of Daughters be not without any just reason, more neglected than that Catherine Turner Bryce, in Elementary Education, of Sons.” One of his classmates wrote that “Hale was becomes the first woman Assistant Professor. triumphant. He was the champion of the daughters and 1923 most ably advocated their cause.” The Yale School of Nursing is established under Dean DECEMBER 1783 Annie Goodrich, the first female dean at Yale. The School Lucinda Foote, age twelve, is interviewed by Yale of Nursing remains all female until at least 1955, the President Ezra Stiles who writes later in his diary: earliest date at which a man is recorded receiving a degree “Were it not for her sex, she would be considered fit to at the school. -

Margaret Deli [email protected] (847) 530 7702 EDUCATION

Margaret Deli [email protected] (847) 530 7702 EDUCATION YALE UNIVERSITY Ph.D., Department of English Language and Literature, May 2019 M.Phil. and M.A. in English Language and Literature, 2014 Dissertation: “Authorizing Taste: Connoisseurship and Transatlantic Modernity, 1880-1959,” directed by professors Ruth Bernard Yeazell (Chair), Joseph Cleary, and R. John Williams UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD M.St. in English and American Studies, 2010 CHRISTIE’S EDUCATION LONDON M.Litt. with Distinction in the History of Art and Art-World Practice, an object-based Master’s program overseen by Christie’s Education, a sector of Christie’s Auction House, focusing on art history, expertise and connoisseurship. Degree granted by the University of Glasgow, 2009 Christie’s Education Trust Scholar JOHNS HOPKINS UNIVERSITY B.A. with Honors in English and Art History, 2008 Hodson Trust Scholar; Phi Beta Kappa TEACHING EXPERIENCE YALE UNIVERSITY, 2014-Present Lecturer in English, Department of English, Language and Literature, 2018-present ENGL 114: “Gossip, Scandal, and Celebrity”: First-year writing seminar challenging students to consider how celebrity is theorized and produced and if it can be disentangled from other features of our consumer economy. The class has a workshop component and prepares students to write well-reasoned analysis and academic arguments, with emphasis on the importance of reading, research, and revision. ENGL 115: “The Female Sociopath”: A literary seminar tracking the relationship between femininity and physical/mental deviance within a broader tradition of western storytelling. The class emphasizes the importance of pre-writing, drafting, revising, and editing, as well as the analysis of fiction, poetry, drama, and nonfiction prose. -

University Humanities Committee 2018-19

University Humanities Committee 2018-19 Amy Hungerford (Chair) Amy Hungerford is Bird White Housum Professor of English and Dean of Humanities at Yale. She specializes in 20th- and 21st-century American literature, especially the period since 1945. Her new monograph, Making Literature Now (Stanford, 2016) is about the social networks that support and shape contemporary literature in both traditional and virtual media. A hybrid work of ethnography, polemic, and traditional literary criticism, the book examines how those networks shape writers’ creative choices and the choices we make about reading. Essays from the project have appeared in ALH and Contemporary Literature. Prof. Hungerford is also the author of The Holocaust of Texts: Genocide, Literature, and Personification (Chicago, 2003) and Postmodern Belief: American Literature and Religion Since 1960 (Princeton, 2010) and serves as the editor of the ninth edition of the Norton Anthology of American Literature, Volume E, “Literature Since 1945” (forthcoming in 2016). Francesco Casetti Francesco Casetti is the author of six books, translated (among other languages) in French, Spanish, and Czech, co-author of two books, editor of more than ten books and special issues of journals, and author of more than sixty essays. Casetti is a member of the Advisory Boards of several film journals and research institutions. He sits in the boards of MaxMuseum, Lugano (Switzerland), and MART museum (Rovereto (Italy). He is a member of the Historical Accademia degli Agiati (Rovereto, Italy), correspondent member of the Historical Accademia delle Scienze (Bologna), and foreigner member of the Historical Accademia di Scienze Morali e Politiche (Naples). He is General Editor of the series “Spettacolo e comunicazione” for the publishing house Bompiani (Milano). -

Wise Traditions

NUTRIENT-DENSE FOODS TRADITIONAL FATS LACTO-FERMENTATION BROTH IS BEAUTIFUL Wise $12 US THE WESTON A. PRICE FOUNDatION® Traditions THERAPIES NURTURING PARENTING PREPARED FARMING NON-TOXIC LABELING IN TRUTH ALERT! SOY for WiseTraditions Non Profit Org. IN FOOD, FARMING AND THE HEALING ARTS U.S. Postage Education Research Activism PAID #106-380 4200 WISCONSIN AVENUE, NW Suburban, MD Wise WASHINGTON, DC 20016 Permit 4889 Traditions IN FOOD, FARMING AND THE HEALING ARTS Volume 16 Number 1 Spring 2015 Spring 2015 ® HE ESTON RICE OUNDatION T W A. P F for WiseTraditions IN FOOD, FARMING AND THE HEALING ARTS Education Research Activism Volume NUTRIENT DENSE FOODS TRADITIONAL FATS LACTO-FERMENTATION BROTH IS BEAUTIFUL A CAMPAIGN FOR REAL MILK TRUTH IN LABELING 16 PREPARED PARENTING SOY ALERT! LIFE-GIVING WATER Number Cleansing Myths and Dangers Toxicity and Chronic Illness Gentle Detoxification NON-TOXIC FARMING PASTURE-FED LIVESTOCK NURTURING THERAPIES Great Nutrition Pioneers COMMUNITY SUPPORTED AGRICULTURE 1 The Fats on MyPlate Cooking with Blood A PUBLICatION OF THE WESTON A. PRICE FOUNDatION® You teach, you teach, you teach! Education Research Activism Last words of Dr. Weston A. Price, January 23, 1948 www.westonaprice.org COMMUNITY SUPPORTED AGRICULTURE LIFE-GIVING LIVESTOCK WATER FOR REAL MILK PASTURE-FED A CAMPAIGN Printed on Recycled Offset Printed with soy ink - an appropriate use of soy TECHNOLOGY AS SERVANT SCIENCE AS COUNSELOR KNOWLEDGE AS GUIDE 150123_cover.indd 1 3/24/15 7:07 AM WiseTraditions THE WESTON A. PRICE Upcoming Events IN FOOD, FARMING AND THE HEALING ARTS ® Volume16 Number 1 FOUNDatION Spring 2015 Education Research Activism 2015 EDITORS Sally Fallon Morell, MA The Weston A. -

Role of Vitamin a Status and Its Catabolism in the Regulation of Glucose and Lipid Homeostasis in Rats Under Physiological and Disease Conditions

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-2014 Role of vitamin A status and its catabolism in the regulation of glucose and lipid homeostasis in rats under physiological and disease conditions Yang Li University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Molecular, Genetic, and Biochemical Nutrition Commons Recommended Citation Li, Yang, "Role of vitamin A status and its catabolism in the regulation of glucose and lipid homeostasis in rats under physiological and disease conditions. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2014. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/3150 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Yang Li entitled "Role of vitamin A status and its catabolism in the regulation of glucose and lipid homeostasis in rats under physiological and disease conditions." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Nutritional Sciences. Guoxun Chen, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Jay Whelan, Ling Zhao, Michael Karlstad Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. -

Water Management Plan

Yale University Water Management Plan Update 2017 Office of Facilities July 2017 Yale University Water Management Plan Update 2017 Office of Facilities July 2017 4 Contents 7 Introduction 8 Vision for Water Management 9 Progress to Date 15 Moving Forward 18 Conclusion 19 Appendix Table 1: Water Meter and Building Account Priorities Acknowledgments 5 6 Introduction In 2013, the Yale Water Management Plan 2013–2016 was released, detailing the importance of water management on campus; various approaches taken to date with campus metering, building, irrigation, and process systems; and method- ology for analyzing water data and metrics. The plan also presented a suite of strategies identified toward a university-wide 5% water-use reduction goal. In 2016, the Office of Sustainability released the Yale Sustainability Plan 2025, which presents a comprehensive approach to connect scholarship and opera- tions at Yale under one sustainability vision. The plan sets a specific goal “to update the campus water management plan in alignment with local priorities.” This document provides an update to the Water Management Plan 2013–2016 and initial fulfillment of the Yale Sustainability Plan 2025. Moving forward, the University intends to incorporate water management progress and plan- ning into the Campus Resilience Plan, High Performance Design Standards, Sustainability Progress Reports, and supporting documents. Collectively, these plans invite generative work and collaboration between the academic and operational sides of the University. The significance of operational com- mitments is expanded beyond Yale’s campus with related applied research, teaching, and service. Yale University — Water ManageMent Plan — Update 2017 7 Vision for Water Management Yale University envisions a campus where water is actively and adaptively managed as a highly valuable resource. -

ST JOHN's COLLEGE COUNCIL Agenda for the Meeting Of

ST JOHN’S COLLEGE COUNCIL Agenda For the Meeting of Wednesday, December 3, 2014 Meal at 5:30, Meeting from 6:00 in the Cross Common Room (#108) 1. Opening Prayer 2. Approval of the Agenda 3. Approval of the September 24, 2014 Minutes 4. Business arising from the Minutes 5. New Business a) Update on the work of the Commission on Theological Education b) University of Manitoba Budget situation c) Draft Report from the Theological Education Commission d) Report from Warden on the Collegiate way Conference e) Budget Summary f) Summary of Awards 6. Reports from Committees, College Officers and Student Council a) Reports from Committees – Council Executive, Development, Finance & Admin. b) Report from Assembly c) Report from College Officers and Student Council i) Warden ii) Dean of Studies iii) Development Office iv) Dean of Residence v) Chaplain vi) Bursar vii) Registrar viii) Senior Stick 7. Other Business 8. Adjournment Council Members: Art Braid; Bernie Beare; Bill Pope; Brenda Cantelo; Christopher Trott; David Ashdown; Don Phillips; Heather Richardson; Ivan Froese; Jackie Markstrom; James Ripley; Joan McConnell; June James; Justin Bouchard; Peter Brass; Sherry Peters; Simon Blaikie; Susan Close; William Regehr, Susie Fisher Stoesz, Martina Sawatzky; Diana Brydon; Esyllt Jones; James Dean; Herb Enns ST JOHN’S COLLEGE COUNCIL Minutes For the Meeting of Wednesday, September 24, 2014 Present: B. Beare (Chair), A. Braid, J. Bouchard, B. Cantelo, D Brydon, J. Ripley, P. Brass, M. Sawatzky, B. Regehr, C. Trott, S. Peters (Secretary), J. Markstrom, H. Richardson, I. Froese, J. McConnell, B. Pope. Regrets: J. James, D. Phillips, H. Enns, S. -

Di-Ver-Si-Ty, N.*

Di-ver-si-ty, n.* *Define yourself at Yale, 2017–2018 A yale_diversity_2017_final_gr1.indd 1 9/1/17 8:51 AM B We’ve designed this piece to make you think. Our aim is not simply to provide our take on diversity, but also to motivate you to consider the idea for yourself. You may believe that you already know what we’re going to say about diversity at Yale, and you may bring thoughts of your own about diversity to measure ours against. With this in mind, here’s a preliminary exercise that may be productive. Take out a pen and, in the empty box below, write down a few thoughts in response to these questions: How is Yale going to define “diversity”? How would I define it? Not feeling 100% satisfied with what you’ve written? Neither were we when we sent this piece o≠ to the printing press. Among other things, a liberal education is a liberating education. Your definitions are always going to be working definitions, subject to continual dissatisfaction and revision. Read on to see how far we got this time. 1 yale_diversity_2017_final_gr1.indd 1 9/1/17 8:52 AM At Yale, we think broadly about the word diversity, and we see it manifest in countless ways here in New Haven. Diversity. Diversity of thought powers our classrooms We hear that word a lot in and labs, where Yale students bring varied national, local, and campus academic interests and intellectual strengths to conversations, and we bet bear on collaborative, world-class scholarship. Socioeconomic diversity it’s turning up everywhere means that we in your college search. -

Divinity School 2003–2004

Divinity School 2003–2004 bulletin of yale university Series 98 Number 5 July 25, 2003 Bulletin of Yale University Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, PO Box 208227, New Haven ct 06520-8227 PO Box 208230, New Haven ct 06520-8230 Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut Issued sixteen times a year: one time a year in May, November, and December; two times a year in June and September; three times a year in July; six times a year in August Managing Editor: Linda Koch Lorimer Editor: David J. Baker Editorial and Publishing Office: 175 Whitney Avenue, New Haven, Connecticut Publication number (usps 078-500) The closing date for material in this bulletin was June 20, 2003. The University reserves the right to withdraw or modify the courses of instruction or to change the instructors at any time. ©2003 by Yale University. All rights reserved. The material in this bulletin may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, in any form, whether in print or electronic media, without written permission from Yale University. Photo credits: Gabriel Amadeus Cooney, Robert A. Lisak, Jamie L. Manson, Michael Mars- land, Frank Poole, Sheryl Serviss Inquiries Requests for catalogues and application material should be addressed to the Office of Admis- sions, Yale University Divinity School, 409 Prospect Street, New Haven, Connecticut 06511, telephone 203.432.5360, fax 203.432.7475. Web site: www.yale.edu/divinity Divinity School 2003Ð2004 bulletin of yale university Series 99 Number 5 July 25, 2003 yale univer s ity campus nort h Continued on next page yale univer s ity campus south & yale medical cent er ©Yale University. -

Divinity School 2010–2011

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut Divinity School 2010–2011 Divinity School Divinity 2010–2011 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 106 Number 3 June 20, 2010 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 106 Number 3 June 20, 2010 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 status as a special disabled veteran, veteran of the Vietnam era, or other covered veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation Managing Editor: Linda Koch Lorimer or gender identity or expression. Editor: Lesley K. Baier University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, special disabled veterans, veterans of the Vietnam era, and other covered veterans. -

IOWNER of PROPERTY NAME Trumbull Associates, Mr

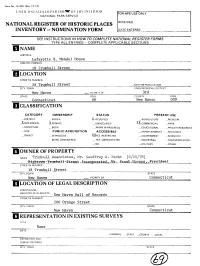

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UN1TI-D SI A IKS UhPART MHTWOF THt. INTERIOR. FOR NFS USE ONLY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVED INVENTORY « NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ NAME HISTORIC Lafayette B. Mendel House AND/OR COMMON 18 Trumbull Street [LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 18 Trumbull Street —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT New Haven — VICINITY OF 3rd STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Connecticut 09 New Haven 009 UCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENTUSE -^DISTRICT —PUBLIC X-OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED XX_cOMMERCIAL — PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT — RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS KXYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT -.-SCIENTIFIC _ -BEING CONSIDERED _YES UNRESTRICTED ^.INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Trumbull Associates, Mr. Geoffrey A. Hecht (6/20/78) Eighteen -Trumtrolrlr -Street -InGQgpcreat&d r -Me ^ -Enank -Movar-o ,. -PrestdeHt STREET & NUMBER 18 Trumbull Street CITY. TOWN STATE New Haven VICINITY OF Connecticut LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Q£ STREETS NUMBER . Orange Street CITY, TOWN STATE New Haven Connecticut REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE None DATE — FEDERAL -STATE __COUNTY .. .LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED XX UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD Restored —RUINS —ALTERED —MOVED DATE. -FA1R xT~Unrestored -UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Eighteen Trumbull Street, the Lafayette B. Mendel House, is located in New Haven, Connecticut. The house is a two-and-one-half story brick building. -

“FOOD, YOUR FRIEND OR FOE” an Inaugural Lecture

UNIVERSITY OF PORT HARCOURT “FOOD, YOUR FRIEND OR FOE” An Inaugural Lecture By Professor (Mrs) Joyce Oronne Akaninwor BSc. MSc. (UNIBEN), PhD (UNIPORT), FHNR Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science INAUGURAL LECTURE SERIES NO. 131 28TH April, 2016. i DEDICATION I dedicate this inaugural lecture to: The Almighty, Omnipresent and Omniscient God. My Parents, Late Ven. S. Y. Chukuigwe (Rtd) and Matron I. C. Chukuigwe (Rtd). My darling husband, Late Sir N.N. Akaninwor, loving children: Buduka, Chinwe, Habinuchi, Manuchimso, Akpenuchi and grandchild, Maxwell Manuchimso Ndy Wenenda. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Vice Chancellor Sir, permit me to appreciate and acknowledge those that made this day of my academic outing possible. First, I acknowledge my darling, amiable and charming husband, Late Sir N.N. Akaninwor for the privilege and support he gave me to work and study at the same time, irrespective of certain deprivations he must have experienced due to useful time I spent on academic work at the expense of family chores. My thanks go to my beloved children, Buduka, Chinwe, Habinuchi, Manuchimso and Akpenuchi who have always been my succour in times of tribulations as I was bearing and nurturing them alongside my studies and work; a task that was not very easy for all of us in all ramifications. My tribute goes to my Parents, Late Ven. S. Y. Chukuigwe (Rtd) and Matron I. C. Chukuigwe (Rtd) who made sure I was educated even when a girl-child education was not of priority, as well as my aunt, Chief (Dame) Eunice Igwe and her late husband, Sir I. Elechi Igwe, who nurtured me to what I am prior to my marriage; they were all indeed, my role models.