Are Resettled Oustees from the Sardar Sarovar Dam Project Better Off Today Than Their Former Neighbors Who Were Not Ousted?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 5107-IN STAFF APPRAISAL REPORT Public Disclosure Authorized INDIA NARMADARIVER DEVELOPMENT- GUJARAT SARDAR SAROVARDAM AND POWERPROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized February 12, 1985 Public Disclosure Authorized South Asia Projects Department Irrigation II Division This document has a restricteddistribution and cmaybe used by recipients only in the performanceof their official duties. its contents mnavnot otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCYEQUIVALENTS US%1.00 = Rupees (Rs) 12.00 jj WEIGHTS AND MEASURES (METRIC SYSTEM) VJ 1 meter (m) = 3.28 feet (ft) 1 kilometer (ka) = 0.62 miles (mi) 1 hectare (ha) = 2.47 acres (ac) 1 million cubic meters (Mm3) = 810 acre-feet (ac-ft) 1 cubic foot per second (cusec or cfs) = 0.028 cubic meters per second (mL3/Ls) 1 kilogram (kg) = 2.2 pounds (lb) 1 metric ton (mt) = 2,205 pounds (lb) 1 million acre-feet (OAF) 1233.5 h cubic m (Mm3) 1 cubic meter per second (cumec) 35.3 cusec 1 ton - 1,000 kilograms (kg) 1 gigawatt hours (GWh) 1 million kilowvtt hours (kWh) 1 kilo volt (kv) - 1,000 volts (10 V) 1 megawatt (MW) = 1,000 kilowatts 1 kilocalorie per kilogram (Kcal/kg) = 1,8UO British thermal units per pound (Btu/lb) FISCAL YEAR GOI; GOG; GOM; GOMP; GOR April 1 - March 31 1/ The US Dollar/Rupee exchange rate is subject to change. Conversions in this report have been made at USAl.00 to Rs 12.00 except for the economic analysis which was made at a rate of US$1.00 to Rs 11.00. -

“A Visit to Sardar Sarovar Dam”

“A VISIT TO SARDAR SAROVAR DAM” 23rd September 2017 Coordinator ORGANIZED BY J. S. Makadiya CIVIL DEPARTMENT S. M.DOBARIYA PREPARED BY D R SOLANKI J S MAKADIYA K.P.BARAD 1 CONTENT (1) Acknowledgement 03 (2) General Information 04 (3) Purpose of Visit 05 (4) Learning Point 06 (5) Conclusion 13 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT We are gladly thankful to Head of the Department Civil Engg. for providing such great opportunities to learn something new and innovative and our faculties who gave us a great guidance regarding training and instructed us the importance of training in civil field. So we decided to take visit in Sardar Sarovar Narmada dam, near Navagam. 3 GENERAL INFORMATION Narmada Dam & sardar sarovar are one of the largest water resources of India covering four major states - Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat and Rajasthan. Dam's spillway discharging capacity is 30.7 lakhs cusecs. Narmada Main Canal' s length is 532 km and it is the largest irrigation canal in the world with 1133 cumecs (40000 cusecs) capacity at the head regulator. It is the largest dam and part of the Narmada Valley Project, a large hydraulic engineering project involving the construction of a series of large irrigation and hydroelectric multi-purpose dams on the Narmada river. 4 PURPOSE OF VISIT Our main purpose for this visit is to be familiar with industrial environment and to get practical knowledge of Hydraulic structure of dam and Hydro power plant in dam. Also in 5th semester subject like Irrigation engineering requires knowledge about how components of dam and hydro power plant are constructed, so it is very much convenient to see all the practical and components in real time work environment. -

SARDAR SAROVAR DAM VISIT REPORT.Pdf

A REPORT ON Industrial Visit for Mechanical Department 4 th & 6 th Sem. Degree Students At SARDAR SROVAR DAM Date of Visit : 7th February, 2019 Branch : MECHANICAL Time : 09:00 am – 01:30 pm Semester : 4th & 6th Faculty : Nikunj Sonaiya & Milan Gajera Department of Mechanical engineering from OM Engineering College arranged one day Industrial Visit for 4 th & 6 th Semester Degree students to “SARDAR SROVAR DAM dated 7th february, 2018 for better technical knowledge enhancement of students. Visit is important especially important in the field of Engineering as the practice of engineering has an inherent (and unavoidable) impact on society. These programs can be a powerful tool to constitute a positive industrial climate. Overall, the aim of all these visit to trains the students to familiar about power generation process. After visit students can identify their own efficiency and performance which important for their career, improving work efficiency and confidence. Purpose: Industrial visits are an integral part of Engineering and acknowledgment of technological up- gradation. The purpose of industrial visit for students is to provide technical knowledge with the technological development in the industry and to understand the gap between the theoretical and practical knowledge that could be passed in future. This experience can help students to provided information regarding functioning of various industries and associated problems and limitations. Interfacing with the industry also provide a chance to build networks and hone their communication skills. Moreover, the participating organizations also gain by getting refined students from the respective institute which could also help in improving their economy. 1. HISTORY The plan for harnessing the river for irrigation and power generation in the Narmada basin was initiated in 1946. -

A Case Study of Gujarat State, India Dr

The role of water technology in development: a case study of Gujarat State, India Dr. Rajiv Kumar Gupta, IAS, Government of Gujarat, Republic of India Type of tool: technology Location: Gujarat State, India Introduction This article traces the historical water problem in Gujarat both for drinking and irrigation that affected the development of the State, caused regional imbalances and increased incidence of rural poverty. Technological initiatives like the State Wide Water Grid, Micro Water Harvesting, Inter-Basin Transfer of Water and Power Sector Reforms have changed the entire water scenario in the State. There has been a great deal of emphasis on peoples’ participation in water governance as well. Water challenges in Gujarat Gujarat has just 2.28% of India’s water resources and 6.39% of country’s geographical area. This is again constrained by imbalances in intra-state distribution. The State has an average annual rainfall of 80 cm with a high coefficient of variance over time and space and as a result droughts have been frequent. Out of 185 rivers, the State has only eight perennial rivers and all of them are located in southern part. Around 80% of the State’s surface water resources are concentrated in central and southern Gujarat, whereas the remaining three-quarters of the State has only 20%. On average, three years in a cycle of 10 years have been drought years. Since Indian independence in 1947, the drought years of Gujarat have been as follows: 1951, 1952, 1955, 1956, 1957, 1962, 1963, 1965, 1968, 1969, 1972, 1974, 1980, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1991, 1999, 2000 and 2003 (Gupta, 2004). -

Performance and Development Effectiveness of the Sardar Sarovar Project

PERFORMANCE AND DEVELOPMENT EFFECTIVENESS OF THE SARDAR SAROVAR PROJECT TATA INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES (A Deemed University) V.N. Purav Marg, Deonar Mumbai 400088 INDIA www.tiss.edu ____________________________________________________________________________ Cover Photograph, Design and Layout : Mukund Sawant, TISS, Mumbai Text Layout, Design and Typesetting : Publications Unit, TISS, Mumbai Printing : Specific Assignments, Parel, Mumbai – 40 011 ii CONTENTS Preface iv Executive Summary vi Chapter 1 Sardar Sarovar Project: Examining Social, Environmental 1 and Financial Costs Chapter 2 Sardar Sarovar Project: Benefits Realised? 58 Chapter 3 Concluding Observations 90 Appendices 92 Appendix 1 Chronology of Events 92 Appendix 2 Extract from Directions Regarding Submergence, Land 99 Acquisition and Rehabilitation of the Displaced Persons Appendix 3 Case Studies 100 Appendix 4 Graphs 102 iii PREFACE The Tata institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai, was the official agency for Monitoring and Evaluation of Resettlement and Rehabilitation of people displaced in Maharashtra by the Sardar Sarovar Project (SSP) from 1987 to 1994. During this period, the TISS developed baseline data on social, demographic, economic, cultural and environmental aspects of individuals, families and communities in 33 villages in Akkalkuwa and Akrani tehsils of Dhule (now Nandurbar) district, and tracked changes in the habitat and life conditions of people shifted from Manibeli, Dhankhedi, and Chimalkhedi villages to Parveta (one of the earliest resettlement sites in Gujarat). While TISS moved out of its monitoring and evaluation role in 1994, it continued to track the progress made on various aspects of the SSP. Dam height has been steadily increasing and reached 121.92 m in October 2006; the final and pending phase of installing radial gates will take the dam height to 138.68 m. -

1 India's Sardar Sarovar Project

India’s Sardar Sarovar Project (SSP) (Unpublished 2003 T.Scudder Manuscript) Introduction During the 1980s, my major river basin fieldwork aside from Kariba concerned India’s Sardar Sarovar (SSP) and China’s Three Gorges Projects. Along with the binational Lesotho Highlands Water Project where I began annual visits in 1989, and the Accelerated Mahaweli Project, these projects are among the largest undergoing construction during the initial years of the 21st century. As with the Aswan High Dam, my assessment will emphasize resettlement aspects, but with one major difference. In the High Dam case, a credible and relatively successful resettlement process was completed. In the Sardar Sarovar case, the refusal of the project authorities at the central and state levels to plan and execute even a minimal resettlement program has become the main constraint to project implementation as well as the focal point at the national and international levels for a globally relevant dialogue on opposing development paradigms. As initially planned the key feature of SSP was to be a 138 meter high dam across the Narmada River in eastern Gujarat that is to provide irrigation water for 1.8 million hectares and have hydropower installed capacity of 1,450 megawatts. How what the Indians refer to as Resettlement and Rehabilitation 1 was to be carried out was stipulated by the 1979 report of the Narmada Water Disputes Tribunal (the Tribunal). Because the project authorities have ignored the Tribunal’s provisions from the start, opposition began to build up in the early and mid 1980s. Several NGOs were involved. Initially their main concern was to improve the resettlement process according to the Tribunal and the guidelines of the World Bank. -

The Sardar Sarovar Dam Project: Selected Documents Level

Chapter 1 The Sardar Sarovar Dam Project: An Overview Philippe Cullet The Sardar Sarovar Project (SSP) is part of a gigantic scheme seeking to build more than 3,000 dams, including 30 big dams, on the river Narmada, a 1,312 km river flowing westwards from Amarkantak in Madhya Pradesh, touching Maharashtra and ending its course in Gujarat. The SSP is a multi-purpose dam and canal system whose primary rationale is to provide irrigation and drinking water. Power generation is another expected benefit. It is the second biggest of the proposed dams on the Narmada, and its canal network is projected to be the largest in the world. The dam is situated in the state of Gujarat, which will derive most of the benefits of the project, but the submergence – 37,533 hectares in total – is primarily affecting the state of MP (55 per cent) and to a much lesser extent the state of Maharashtra. The SSP has been one of the most debated development projects of the past several decades in India and at the international level. It is only one of many similar big projects in the Narmada valley and in India generally but it has acquired a symbolic status in development debates. This is due in part to the complexity of such multi-purpose projects and the multiple positive and negative impacts associated with big dams. This is also due to the specificities of this project, which was first proposed nearly 60 years ago. Firstly, the fact that this project involves four states – Gujarat, MP, Maharashtra and Rajasthan – with the state of Gujarat receiving most of the benefits of the project has repeatedly led to disagreements among the concerned states. -

Brief History Jurisdiction Gauge-Wise Break up of The

BRIEF HISTORY Vadodara Division came into existence on August 1st, 1956, when the erstwhile districts of Western Railway were regrouped into Division. Later, Jhund-Kandla and Ahmedabad-Gandhinagar (Capital) section were opened on September 16th, 1969 and April 1st, 1976 respectively. With effect from 1st April 2003, Ahmedabad Division has become operational and part of Vadodara Division has been merged with the new Division. JURISDICTION Vadodara division extends from the west bank of the Tapti river in the south to Geratpur in the north serving industrial and agricultural rich districts of Ahmedabad, Kheda, Annand, Vadodara, Surat, and the developing districts of Bharuch, Sabarkantha, Narmada, Chottaudepur and Panchmahals through the BG and NG net work. The jurisdiction of Vadodara Division on the Broad Guage extends from Surat (excluding) to Godhra on Mumbai – Delhi trunk 'A' route, Vadodara –Geratpur on 'B' route. The division has extensive network of NG comprising a major portion of the old Gaekwad Vadodara State Railway and other isolated sections. GAUGE-WISE BREAK UP OF THE DIVISION. Guage Route-Kms Track-Kms No. of Stations BG 799.387 1084.328 123 NG 432.381 432.381 67 Total 1231.768 1516.709 190 Vasad-Kathana, Anand-Khambhat and Nadiad-Modasa, Pratapnagar – Dabhoi which are branch lines on both these trunk routes and have been converted to BG from NG. DETAILS OF STATIONS Class Number of stations BG NG B 38 04 D 41 47 SPL 44 16 Total 123 67 DETAILS OF LEVEL CROSSINGS Class No. of Manned L.C. No. of Unmanned L.C. BG NG BG NG SPL 27 03 - - A 17 01 - - B 32 07 - - C 211 57 150 463 D - - 002 001 Total 287 68 152 464 DETAILS OF LOCO HOLDING Diesel NG-26 ZDM5 (Pratapnagar) Electric BG - 177 (Vadodara Shed) 32 WAP5 66 WAP4 03 WAM4 22 WAG5HA 54 WAG5A Total 177 DETAILS OF COACH HOLDING ANND 68 (BG) DB 73 (NG) ART/ARME (ISO – 9001:2000 CERTIFIED) ART (Class B) 1- Vadodara Yard SPARMV Scale I 1- Vadodara station. -

Navaratri of Gujarat Tour Package

Tour Code : AKSR0345 Tour Type : FIT Package 1800 233 9008 NAVARATRI OF GUJARAT www.akshartours.com TOUR PACKAGE - 05 Days 4 Nights / 5 Days PACKAGE OVERVIEW 1Country 4Cities 5Days 1Activities Accomodation Meal 02 NIGHTS HOTEL ACCOMODATION AT 04 BREAKFAST AHMEDABAD 04 DINNER 02 NIGHTS HOTEL ACCOMODATION AT VADODARA Visa & Taxes Highlights 5% GST EXTRA Accommodation on double sharing Breakfast and dinner at hotel Transfer and sightseeing by pvt vehicle as per program Applicable hotel taxes SIGHTSEEINGS OVERVIEW - Ahmedabad, Vadnagar Baroda, - Sightseeing – Gandhi Ashram, Adalaj Step well, Modhera Sun Temple, Champaner, - Sardar Sarovar Dam, Amul Dairy, Garba SIGHTSEEINGS AHMADABAD Gandhi Ashram A Must-Visit On Any Trip To Ahmedabad Is The Gandhi Ashram On The Banks Of The Sabarmati River. Home To Gandhi From 1917 And 1930, It Was One Of The Key Places From Where The Struggle For Indian Independence Took Shape. It Was From Here In March 12, 1930, That Gandhi Launched The Dandi March To Protest Against The British Salt Law In India. The Cottage Where Gandhi Lived, Hriday Kunj, Tops The List Of Attractions Within The Complex. The Charles Correa-Designed Museum Contains Three Galleries–The Gandhi In Ahmedabad Gallery, The Painting Gallery And The My Life Is My Message Gallery–And Houses The Ashram’s Library. The Museum Is Open Daily From 8.30am To 6.30pm. There’s No Admission Fee. MODHERA Sun temple Modhera is a town in Mehsana district of Gujarat, India. The town is well known for the Sun Temple of Chaulukya era. The town is located on the bank of river Pushpavati. -

List of Dams and Reservoirs in India 1 List of Dams and Reservoirs in India

List of dams and reservoirs in India 1 List of dams and reservoirs in India This page shows the state-wise list of dams and reservoirs in India.[1] It also includes lakes. Nearly 3200 major / medium dams and barrages are constructed in India by the year 2012.[2] This list is incomplete. Andaman and Nicobar • Dhanikhari • Kalpong Andhra Pradesh • Dowleswaram Barrage on the Godavari River in the East Godavari district Map of the major rivers, lakes and reservoirs in • Penna Reservoir on the Penna River in Nellore Dist India • Joorala Reservoir on the Krishna River in Mahbubnagar district[3] • Nagarjuna Sagar Dam on the Krishna River in the Nalgonda and Guntur district • Osman Sagar Reservoir on the Musi River in Hyderabad • Nizam Sagar Reservoir on the Manjira River in the Nizamabad district • Prakasham Barrage on the Krishna River • Sriram Sagar Reservoir on the Godavari River between Adilabad and Nizamabad districts • Srisailam Dam on the Krishna River in Kurnool district • Rajolibanda Dam • Telugu Ganga • Polavaram Project on Godavari River • Koil Sagar, a Dam in Mahbubnagar district on Godavari river • Lower Manair Reservoir on the canal of Sriram Sagar Project (SRSP) in Karimnagar district • Himayath Sagar, reservoir in Hyderabad • Dindi Reservoir • Somasila in Mahbubnagar district • Kandaleru Dam • Gandipalem Reservoir • Tatipudi Reservoir • Icchampally Project on the river Godavari and an inter state project Andhra pradesh, Maharastra, Chattisghad • Pulichintala on the river Krishna in Nalgonda district • Ellammpalli • Singur Dam -

Preparation of EAP for Ukai Dam Using 1D/2D Coupled Hydrodynamic Modelling and Google Earth Image

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Explore Bristol Research Patel, D., Srivastava, P., Singh, S. K., Prieto, C., & Han, D. (2018). Preparation of EAP for Ukai Dam using 1D/2D coupled hydrodynamic modelling and Google Earth image. Paper presented at International Dam Safety Conference 2018, India. Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the conference organiser. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/pure/about/ebr-terms International Dam Safety Conference - 2018 23-24 January 2018, Thiruvananthapuram PREPARATION OF EAP FOR UKAI DAM USING 1D/2D COUPLED HYDRODYNMAIC MODELING AND GOOGLE EARTH IMAGE DHRUVESH PATEL1, PRASHANT SRIVASTAVA2, SUDHIR KUMAR SINGH3, CRISTINA PRIETO4, DAWEI HAN5 1Department of Civil Engineering, School of Technology, PDPU, Gandhinagar, Gujarat, India 2Institute of Environment and Sustainable Development, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India 3K. Banerjee Centre of Atmospheric and Ocean studies, University of Allahabad, India 4Environmental Hydraulics Institute “IH Cantabria”, University of Cantabria, Santander, Spain 5Department of Civil Engineering, University of Bristol, Bristol, U.K. *Correspondence: <[email protected]> ABSTRACT Ukai is the second largest masonry gravity Dam after Sardar Sarovar Dam in Gujarat. Surat, the diamond hub of India and 2nd largest city of Gujarat state is situated 100 km downstream (D/S) of Ukai dam and 19.4 km upstream (U/S) from Arabian Sea. -

Sardar Sarovar Report Avpi.Pdf

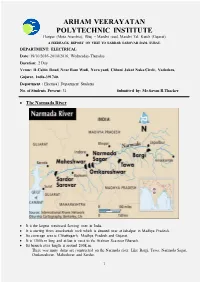

ARHAM VEERAYATAN POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE Haripar (Mota Asambia), Bhuj – Mandvi road, Mandvi Tal. Kutch (Gujarat) A FEEDBACK REPORT ON VISIT TO SARDAR SAROVAR DAM, SURAT. DEPARTMENT: ELECTRICAL Date: 19/10/2016-20/10/2016, Wednesday-Thursday Duration: 2 Day Venue: D-Cabin Road, Near Ram Wadi, Nava yard, Chhani Jakat Naka Circle, Vadodara, Gujarat, India-391740. Department : Electrical Department Students No. of Students Present: 31 Submitted by: Mr.Savan R.Thacker The Narmada River It is the largest westward flowing river in India. It is starting from amarkantak rock which is situated near at Jabalpur in Madhya Pradesh. Its coverage area is Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat. It is 1300k.m long and at last is meet to the Arabian Sea near Bharuch. Its branch river length is around 200k.m. There was many dams are constructed on the Narmada river. Like Bargi, Tawa, Narmada Sagar, Omkareshwar, Maheshwar and Sardar. 1 Introduction about Sardar sarovar Dam The Sardar Sarovar Dam is a gravity dam on the Narmada river near Navagam, Gujarat in India. It is the largest dam and part of the Narmada Valley Project, a large hydraulic engineering project involving the construction of a series of large irrigation and hydroelectric multi-purpose dams on the Narmada river. The project took form in 1979 as part of a development scheme to increase irrigation and produce hydroelectricity. One of the 30 dams planned on river Narmada, Sardar Sarovar Dam (SSD) is the largest structure to be built. Following a number of controversial cases before the Supreme Court of India (1999, 2000, 2003), by 2014 the Narmada Control Authority had approved a series of changes in the final height – and the associated displacement caused by the increased reservoir, from the original 80 m (260 ft) to a final 163 m (535 ft) from foundation.