IAN PACE, P Iano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pace Final 26.11.15

Positions, Methodologies and Aesthetics in the Published Discourse about Brian Ferneyhough: A Critical Study Ian Pace1 Since Brian Ferneyhough achieved a degree of public recognition following the premiere of his Transit (1972-75) in March 1975 at the Royan Festival, a range of writings on and reviews of his work have appeared on a relatively regular basis. The nature, scope, style, and associated methodologies of these have expanded or changed quite considerably over the course of Ferneyhough's career––in part in line with changes in the music and its realization in performance––but nonetheless one can discern common features and wider boundaries. In this article, I will present a critical analysis of the large body of scholarly or extended journalistic reception of Ferneyhough's work, identifying key thematic concerns in such writing, and contextualizing it within wider discourses concerning new music. Several key methodological issues will be considered, in particular relating to intentionality and sketch study, from which I will draw a variety of conclusions that apply not only to Ferneyhough, but to wider contemporary musical study as well. Early Writings on Ferneyhough The first extended piece of writing about Ferneyhough's work was an early 1973 article by Elke Schaaf2 (who would become Ferneyhough's second wife),3 which deals with Epicycle (1968), Missa Brevis (1969), Cassandra's Dream Song (1970), Sieben Sterne (1970), Firecyle Beta (1969-71), and the then not-yet-complete Transit. Schaaf’s piece already exhibits one of the most -

D4.2 BIC Annual Forum and IAG Meeting

D4.2 BIC Annual Forum and IAG meeting Grant Agreement 258655 number: Project acronym: BIC Project title: Building International Cooperation for Trustworthy ICT: Security, Privacy and Trust in Global Networks & Services Funding Scheme: ICT Call 5 FP7 Project co-ordinator: James Clarke Programme Manager Waterford Institute of Technology Tel: +353-71-9166628 Fax: + 353 51 341100 E-mail: [email protected] Project website http://www.bic-trust.eu address: Revision: Final Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Sixth Framework Programme (2002-2006) Dissemination Level PU Public up to and including Annex III RE Annex IV (IAG meeting minutes) Building International Cooperation for Trustworthy ICT: Security, Privacy and Trust in Global Networks & Services 1st Annual Forum 29th November 2011 Brussels, Belgium BIC Partners BIC is a Coordination Action Project within the European Commission, DG INFSO Unit F5, Trust and Security Jan. 2011—Dec. 2013 http://www.bic-trust.eu Page 2 / 103 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................5 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................6 MISSION AND OBJECTIVES OF THE ANNUAL FORUM ...................................6 AGENDA...............................................................................................................7 RESULTS OF THE ANNUAL FORUM..................................................................8 Panel session 1. Other INCO-related -

IAN PACE – Piano with Anna Vaughan, Viola; Charlotte Beale, Flute

IAN PACE – Piano with Anna Vaughan, viola; Charlotte Beale, flute Recital at City University, London Friday June 2nd, 2017, 7:00 pm ARTHUR LOURIÉ Forms en l’air (1915) SOOSAN LOLAVAR Black Dog for piano and live electronics (2012) STEFAN WOLPE Passacaglia (1936, rev. 1972) MARC YEATS william mumler’s spirit photography (2016) [World Premiere] LAUREN REDHEAD for Luc Brewaeys (2016) [UK Premiere] LUC BREWAEYS Nobody’s Perfect (Michael Finnissy Fifty) (1996) LUC BREWAEYS/ The Dale of Tranquillity (2004, completed 2017) MICHAEL FINNISSY [World Premiere of completed version] INTERVAL CHARLES IVES Piano Sonata No. 2 “Concord, Mass., 1840-1860” (1916-19, rev. 1920s-40s) 1. Emerson 2. Hawthorne 3. The Alcotts 4. Thoreau ARTHUR LOURIÉ, Forms en l’air (1915) Arthur Lourié (1891-1966) was a Russian composer whose work interacts with the music of Debussy, Busoni and Skryabin, as well as ideas from Futurism and early use of twelve-note complexes. Formes en l’air, which is dedicated to Pablo Picasso, uses a degree of notational innovation, with somewhat disembodied fragments presented on the page, and decisions on tempo and other aspects of interpretation left to the performer. The three short sections each feature a restricted range of gestures and textures, generally of an intimate and sensuous nature. © Ian Pace 2017. SOOSAN LOLAVAR, Black Dog for piano and live electronics (2012) The piece is based on the experience of depression and its effects on creativity. There is a long history of using the term black dog to refer to depression and my starting point for this work was a painting by Francisco de Goya entitled ‘The Dog’. -

BRIAN FERNEYHOUGH COMPLETE PIANO MUSIC 1965-2018 Ian Pace, Piano with Ben Smith, Piano

BRIAN FERNEYHOUGH COMPLETE PIANO MUSIC 1965-2018 Ian Pace, piano with Ben Smith, piano (track 8) CD/set A 1 Invention (1965) 1:55 Epigrams (1966) 2 I 1:12 3 II 0:48 4 III 2:02 5 IV 1:49 6 V 1:08 7 VI 1:48 8 Sonata for Two Pianos (1966) 16:04 Three Pieces (1966-1967) 9 I 3:37 10 II 7:52 11 III 6:42 Lemma-Icon-Epigram (1981) 12 I. Lemma 5:51 13 II Icon 6:22 14 III Epigram 1:34 CD/set B Opus Contra Naturam (2000) 1 I 2:41 2 II 10:46 3 III 3:08 4 Quirl (2011-2013) 11:28 5 El Rey de Calabria (c. 2018) 2:39 Total duration 89:50 THE PIANISTS Ian Pace is a pianist of long-established reputation, specialising in the farthest reaches of musical modernism and transcendental virtuosity, as well as a writer and musicologist focusing on issues of performance, music and society, and the avant-garde. He studied at Chetham’s School of Music, The Queen’s College, Oxford, and, as a Fulbright Scholar, at the Juilliard School in New York with Hungarian pianist György Sándor, and later obtained his PhD at Cardiff University, on ‘The reconstruction of post-war West German new music during the early allied occupation and its roots in the Weimar Republic and Third Reich.’ Based in London since 1993, he has pursued an active international career, performing in 24 countries and at most major European venues and festivals. His vast repertoire, which extends to all periods, focuses particularly upon music of the 20th and 21st centuries. -

Michael Finnissy (Piano)

MICHAEL FINNISSY (b. 1946) THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY IN SOUND CD1: 1 Le démon de l’analogie [28.29] 2 Le réveil de l’intraitable réalité [20.39] Total duration [49.11] CD2: 1 North American Spirituals [23.41] 2 My parents’ generation thought War meant something [35.49] Total duration [59.32] CD3: 1 Alkan-Paganini [13.37] 2 Seventeen Immortal Homosexual Poets [34.11] 3 Eadweard Muybridge-Edvard Munch [26.29] Total duration [74.18] CD4: 1 Kapitalistisch Realisme (met Sizilianische Männerakte en Bachsche Nachdichtungen) [67.42] CD5: 1 Wachtend op de volgende uitbarsting van repressie en censuur [17.00] 2 Unsere Afrikareise [30.35] 3 Etched bright with sunlight [28.40] Total duration [76.18] IAN PACE, piano IAN PACE Ian Pace is a pianist of long-established reputation, specialising in the farthest reaches of musical modernism and transcendental virtuosity, as well as a writer and musicologist focusing on issues of performance, music and society and the avant-garde. He was born in Hartlepool, England in 1968, and studied at Chetham's School of Music, The Queen's College, Oxford and, as a Fulbright Scholar, at the Juilliard School in New York. His main teacher, and a major influence upon his work, was the Hungarian pianist György Sándor, a student of Bartók. Based in London since 1993, he has pursued an active international career, performing in 24 countries and at most major European venues and festivals. His absolutely vast repertoire of all periods focuses particularly upon music of the 20th and 21st Century. He has given world premieres of over 150 pieces for solo piano, including works by Julian Anderson, Richard Barrett, James Clarke, James Dillon, Pascal Dusapin, Brian Ferneyhough, Michael Finnissy (whose complete piano works he performed in a landmark 6- concert series in 1996), Christopher Fox, Volker Heyn, Hilda Paredes, Horatiu Radulescu, Frederic Rzewski, Howard Skempton, Gerhard Stäbler and Walter Zimmermann. -

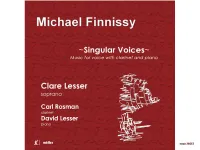

Michael Finnissy Singular Voices

Michael Finnissy Singular Voices 1 Lord Melbourne †* 15:40 2 Song 1 5:29 3 Song 16 4:57 4 Song 11 * 3:02 5 Song 14 3:11 6 Same as We 7:42 7 Song 15 7:15 Beuk o’ Newcassel Sangs †* 8 I. Up the Raw, maw bonny 2:21 9 II. I thought to marry a parson 1:39 10 III. Buy broom buzzems 3:18 11 IV. A’ the neet ower an’ ower 1:55 12 V. As me an’ me marra was gannin’ ta wark 1:54 13 VI. There’s Quayside fer sailors 1:19 14 VII. It’s O but aw ken weel 3:17 Total Duration including pauses 63:05 Clare Lesser soprano David Lesser piano † Carl Rosman clarinet * Michael Finnissy – A Singular Voice by David Lesser The works recorded here present an overview of Michael Finnissy’s continuing engagement with the expressive and lyrical possibilities of the solo soprano voice over a period of more than 20 years. It also explores the different ways that the composer has sought to ‘open-up’ the multiple tradition/s of both solo unaccompanied song, with its universal connotations of different folk and spiritual practices, and the ‘classical’ duo of voice and piano by introducing the clarinet, supremely Romantic in its lyrical shadowing of, and counterpoints to, the voice in Song 11 (1969-71) and Lord Melbourne (1980), and in an altogether more abrasive, even aggressive, way in the microtonal keenings and rantings of the rarely used and notoriously awkward C clarinet in Beuk O’ Newcassel Sangs (1988). -

Download Booklet

Composer’s notes Michael Finnissy Edvard Grieg: Piano Quintet in B flat major (EG 118) Completed by Michael Finnissy Grieg wrote roughly 250 bars of a Piano Quintet in his ‘Kladdebok’ (sketchbook), immediately before the revisions that he made to ‘Peer Gynt’ for performances in 1892. This quintet ‘torso’ constitutes the exposition of a virtually monothematic structure, following Sonata principles similar to those found in Brahms or Franck. He also made some use here of earlier sketches for a second Piano Concerto (1883 - 87). The manuscript, held in the Bergen Public Library, has been published in Volume 20 of the Grieg Gesamtausgabe [C.F.Peters, Frankfurt], and in Edvard Grieg: The Unfinished Chamber Music [A-R Editions, Inc. Middleton, Wisconsin], neither edition attempting to extend the work. My Southampton University colleague Paul Cox suggested that I tried to invent a completion. After some general research and experimentation with the material, I decided to fashion a one-movement Kammersymphonie, in which the central ‘development section’ following on from Grieg’s exposition, consists of a scherzo (a Hailing, with imitation of Hardanger fiddle music) and a ruminative slow movement (in the manner of the Poetic Tone-pictures’ Op.3), which then proceeds to a recapitulation- finale in which some of the material previously assigned to the strings appears in the piano part, and vice versa. This labour of love began in 2007 and produced two successive, but unsatisfactory, versions, both of which were performed in London. Final alterations and revisions were completed in the late Spring of 2012, approximately 120 years after Grieg laid down his pen, and - appropriately enough – received a definitive performance at the 2013 Bergen International Festival, by the Kreutzer String Quartet and Roderick Chadwick. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2001). Interview with Marc Bridle. Seen & Heard, This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/6626/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Interview with Marc Bridle, February 2001 Online at http://www.musicweb-international.com/SandH/2001/Feb01/pace1.htm and http://www.musicweb-international.com/SandH/2001/Feb01/pace2.htm IAN PACE (b.1968) is a leading British pianist, renowned for his transcendental technique and championship of new music in both the UK and Europe, and in recordings. He is currently in the middle of a groundbreaking series of three London recitals attended bySeen&Heard, at the Wigmore Hall, Royal Academy of Music and King's College. In a wide ranging interview with Marc Bridle he discusses his background and musical training, and the egalitarian, anti-nationalist aesthetic and political beliefs which inform his gruelling schedule of varied musical activities, and that led him to seek to present an 'alternative Britain' in his debut CD Tracts recorded in 1997, but which has only now been belatedly released. -

301278 Vol1.Pdf

INTERPRETATIVE ISSUE PERFO CONTEMPORARY PIANO MUSIC J by\ Philip Thomas (Volume I) Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Performance Practice Department of Music University of Sheffield April 1999 SUMMARY This thesis explores practical and theoretical issues in interpreting contemporary notated piano music. Interpretative problems and approaches are discussed with a practical bias, using a varied selection of musical sources mostly from the last fifty years. The diversity of compositional styles and methods over this period is reflected in the diversity of interpretative approaches discussed throughout this thesis. A feature of the thesis is that no single interpretative method is championed; instead, different approaches are evaluated to highlight their benefits to interpretation, as well as their limitations. It is demonstrated how each piece demands its own approach to interpretation, drawing from different methodologies to varying degrees in order to create a convincing interpretation which reflects the concerns of that piece and its composer. The thesis is divided into four chapters: the first discusses the implications and ambiguities of notation in contemporary music; the second evaluates the importance of analysis and its application to performance and includes a discussion of the existing performance practice literature as well as short performer-based analyses of three pieces (Saxton's Piano Sonata, Tippett's Second Piano Sonata, and Feldman's Triadic Memories); the third chapter considers notions of style and performing traditions, illustrating the factors other than analysis that can 'inform' interpretation; and the fourth chapter draws together the processes demonstrated in the previous chapters in a discussion of the interpretative issues raised by Berio's Seguenza IV. -

James Dillon

James Dillon New Music Biography James Dillon James Dillon is one of the UK’s most internationally celebrated and performed composers. The recipient of a number of prizes and awards including the Kranichsteiner Musikpreis and the Japan Foundation Artist Scholarship, he has also won an unprecedented four Royal Philharmonic Society awards, and most recently was awarded a BASCA British Composer Award for Stabat Mater dolorosa. In 1983, Dillon’s First String Quartet received its premiere from the Arditti Quartet at the Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival. The Arditti Quartet has remained closely involved with the composer, having premiered and widely performed Dillon’s subsequent quartets, and Huddersfield is one of the many festivals to regularly feature Dillon’s music, most recently as Composer in Residence in 2014. In 2016, the Arditti Quartet premiered The Gates, for string quartet and orchestra, at Donaueschinger Musiktage. Nine Rivers, an enormous three-and-a-half hour sequence of works composed over more than two decades, was first performed by the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra in 2010 and has subsequently been heard in New York and at the 2013 Holland Festival to great acclaim. It was conceived as a collection of works with ‘internal symmetries’ and is indicative of Dillon’s tendency to think in terms of large-scale, complementary forms. In the mid-1980s, Dillon began a ‘German Triptych’, a set of works based on the idea of ‘illumination as the emanation from darkness’, which Richard Toop described as ‘a music full of figures which, like the stars, are intense, yet seem almost infinitely far away’. -

Program Notes

‘Hear and Now’ Studio Concert Sunday 9 March 2008 7.30pm Studio 1, BBC Broadcasting House, Llandaff, Cardiff Contemporary Music Ensemble of Wales Kenneth Woods conductor Ian Pace piano John Senter cello GORDON DOWNIE Fragments for cello and piano 3’ PAUL MEFANO Interferences – fragments IV,V,VI (UK premiere) 10’ GORDON DOWNIE Piano Piece 3 (Wales premiere) 12’ Interval (15 Minutes) EARLE BROWN Novara 10’ GORDON DOWNIE Forms 7: non-mediated forms for 24 instrumentalists (World premiere) 10’ IANNIS XENAKIS Akrata 12’ This concert will be broadcast on BBC Radio 3’s ‘Hear and Now’ on Saturday 19 March, 2008 at 10.30pm This concert is part of Greece in Britain 2008, a nationwide series of events presented by the Hellenic Foundation for Culture This concert is dedicated to the memory of the writer and new music specialist John Warnaby, who died in January 2007. John, who lived in Port Talbot, was a committed writer and commentator on new music whose contribution to the field will be greatly missed. CMEW acknowledges the financial support of the Arts Council of Wales, the Hinrichsen Foundation and the Hellenic Foundation for Culture. GORDON DOWNIE Paul Mefano received encouragement from Alfred Cortot to study Fragments for cello and piano (1990–2005) music. Later, he studied with Andrée Vaurabourg-Honegger and then at the Conservatoire of Paris with Darius Milhaud and Georges Dandelot. Commissioned by Margaret Reid and Derek Clarke and premiered in He continued his studies with Boulez, Stockhausen and Pousseur in Cardiff, 1990. Basle, attending concerts in the Domain Musical, the Darmstadt summer The majority of Fragments for cello and piano was composed in school and the class of Olivier Messiaen at the C.N.S.M.P In 1965 his 1990.The recent revision and extension in 2005 involved developing and music was performed for the first time under the direction of Bruno re-characterizing certain material.Whilst the earlier material informally Maderna at the Domain Musical. -

CATALOGUE of the WORKS of CHRISTOPHER FOX Further Information from [email protected]

CATALOGUE OF THE WORKS OF CHRISTOPHER FOX Further information from [email protected] Works in chronological order re:play for solo cello with prerecorded soundtrack; for Anton Lukoszevieze. new work for solo soprano with live electronics. Text: Norman Nicholson. Written for Elizabeth Hilliard. From the water for choir (SATB) (3’30”). Texts: St, Matthew’s gospel (chapter 3, verses 1-17) in John Wycliffe’s translation and Henry Vaughan. Commissioned for the 750th anniversary of the founding of Merton College, Oxford; premiere, 2014. The Wedding at Cana (after the Master of the Spanish Kings) for string quartet (c.20′); commissioned by the Sound Festival, Aberdeen; to be premiered by the Edinburgh Quartet in the Sound Festival, Aberdeen, 26 October 2013. suo tormento for vocal consort (SSATB) (6′). Texts by Dante and Gramsci. Commissioned by EXAUDI as part of their Italian Madrigal book; premiere, Wigmore Hall, 6 November 2013. The Dark Roads for voice, viola, keyboard tuned in sixth-tones and sound-files (c.20′). Text by Ian Duhig, commissioned by Trio Scordatura and dedicated to them and to the memory of Horatiu Radulescu; premiere, Tate Britain, 5 April 2013. Two movements, which may also be performed separately, as In the old style and The Dark Road. Tales from Babel for six voices (25′). Text: Edward Wickham. Commissioned by The Clerks with funds from the Wellcome Trust; can be performed separately or as the first part of a two act voice drama of which Roger go to yellow three is the second part. Premiered by The Clerks at the Cheltenham Festival on 7 July 2013.