IAN PACE – Piano with Anna Vaughan, Viola; Charlotte Beale, Flute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pace Final 26.11.15

Positions, Methodologies and Aesthetics in the Published Discourse about Brian Ferneyhough: A Critical Study Ian Pace1 Since Brian Ferneyhough achieved a degree of public recognition following the premiere of his Transit (1972-75) in March 1975 at the Royan Festival, a range of writings on and reviews of his work have appeared on a relatively regular basis. The nature, scope, style, and associated methodologies of these have expanded or changed quite considerably over the course of Ferneyhough's career––in part in line with changes in the music and its realization in performance––but nonetheless one can discern common features and wider boundaries. In this article, I will present a critical analysis of the large body of scholarly or extended journalistic reception of Ferneyhough's work, identifying key thematic concerns in such writing, and contextualizing it within wider discourses concerning new music. Several key methodological issues will be considered, in particular relating to intentionality and sketch study, from which I will draw a variety of conclusions that apply not only to Ferneyhough, but to wider contemporary musical study as well. Early Writings on Ferneyhough The first extended piece of writing about Ferneyhough's work was an early 1973 article by Elke Schaaf2 (who would become Ferneyhough's second wife),3 which deals with Epicycle (1968), Missa Brevis (1969), Cassandra's Dream Song (1970), Sieben Sterne (1970), Firecyle Beta (1969-71), and the then not-yet-complete Transit. Schaaf’s piece already exhibits one of the most -

BRIAN FERNEYHOUGH COMPLETE PIANO MUSIC 1965-2018 Ian Pace, Piano with Ben Smith, Piano

BRIAN FERNEYHOUGH COMPLETE PIANO MUSIC 1965-2018 Ian Pace, piano with Ben Smith, piano (track 8) CD/set A 1 Invention (1965) 1:55 Epigrams (1966) 2 I 1:12 3 II 0:48 4 III 2:02 5 IV 1:49 6 V 1:08 7 VI 1:48 8 Sonata for Two Pianos (1966) 16:04 Three Pieces (1966-1967) 9 I 3:37 10 II 7:52 11 III 6:42 Lemma-Icon-Epigram (1981) 12 I. Lemma 5:51 13 II Icon 6:22 14 III Epigram 1:34 CD/set B Opus Contra Naturam (2000) 1 I 2:41 2 II 10:46 3 III 3:08 4 Quirl (2011-2013) 11:28 5 El Rey de Calabria (c. 2018) 2:39 Total duration 89:50 THE PIANISTS Ian Pace is a pianist of long-established reputation, specialising in the farthest reaches of musical modernism and transcendental virtuosity, as well as a writer and musicologist focusing on issues of performance, music and society, and the avant-garde. He studied at Chetham’s School of Music, The Queen’s College, Oxford, and, as a Fulbright Scholar, at the Juilliard School in New York with Hungarian pianist György Sándor, and later obtained his PhD at Cardiff University, on ‘The reconstruction of post-war West German new music during the early allied occupation and its roots in the Weimar Republic and Third Reich.’ Based in London since 1993, he has pursued an active international career, performing in 24 countries and at most major European venues and festivals. His vast repertoire, which extends to all periods, focuses particularly upon music of the 20th and 21st centuries. -

IAN PACE, P Iano

University of Washington 2001-2002 School ofMusic sc. Presents a Guest Artist Recital: P3 3 4 2. 0 '02 ,-I~ IAN PACE, p iano April 19, 2002 8:00 PM Brechemin Auditorium PROGRAM THREE PIECES FOR PIANO OP. 11 (1909) ..... ..... ....... ... ......... ...... ....... ARNOLD SCHOENBERG 1. Massige ( 1874-1951) / . ' L!::"~, ~ :"" :~~~ :; 3. Bewegte POL VERI LATERALI (1997) ..... ......................... .......... .. ... SALVATORRE SClARRINO (b. 1947) OPUS CONTRA NATURAM (2000-2001) .............................. BRlAN FERNEYHOUGH (b. 1943) INTERMISSION LE CHEMIN (1994) ..... .. .. .... .................... ..... ............... .JOEL-FRANc;:orS DURAND (b. 1954) BAGATELLES OP. 126 (1824) ...................... .. .; .. ...... .. ................. LUDWIG VAN BEETIlOVEN 1. Andante can mota cantabile e compiacevole (1770-1 82 7) 2. Allegro 3. Andante, cantabile e grazioso 4. Presto 5. Quasi allegretto 6. Presto - Andante amabile e can mota ARNOLD SCHOEl\IBERG: THREE PIECES FOR PlANO OP. 11 It was around 1908 that Arnold Schoenberg began to use the piano as a solo instrument. Perhaps no other composition was as crucial to Schoenberg's future, and, if one accepts the eventualities of that future, then also to twentieth-century music, as the Three Piano Pieces Op. 11 . They were not his first atonal works, for besides the last movement of the Second String Quartet, many of the songs in his magnificent cycle Das Buch der hangenden Garten, Op. 15, predated Op. 11. But in tenns of sustained structure (the second of the Three Pieces runs to nearly seven minutes), Op. 11 was the first major test of the possibilities of survival ina musical universe no longer dominated by a triadi cally centered harmonic orbit. And the survival potential was, on the basis of Op. 11, eminently satis factory. -

Michael Finnissy (Piano)

MICHAEL FINNISSY (b. 1946) THE HISTORY OF PHOTOGRAPHY IN SOUND CD1: 1 Le démon de l’analogie [28.29] 2 Le réveil de l’intraitable réalité [20.39] Total duration [49.11] CD2: 1 North American Spirituals [23.41] 2 My parents’ generation thought War meant something [35.49] Total duration [59.32] CD3: 1 Alkan-Paganini [13.37] 2 Seventeen Immortal Homosexual Poets [34.11] 3 Eadweard Muybridge-Edvard Munch [26.29] Total duration [74.18] CD4: 1 Kapitalistisch Realisme (met Sizilianische Männerakte en Bachsche Nachdichtungen) [67.42] CD5: 1 Wachtend op de volgende uitbarsting van repressie en censuur [17.00] 2 Unsere Afrikareise [30.35] 3 Etched bright with sunlight [28.40] Total duration [76.18] IAN PACE, piano IAN PACE Ian Pace is a pianist of long-established reputation, specialising in the farthest reaches of musical modernism and transcendental virtuosity, as well as a writer and musicologist focusing on issues of performance, music and society and the avant-garde. He was born in Hartlepool, England in 1968, and studied at Chetham's School of Music, The Queen's College, Oxford and, as a Fulbright Scholar, at the Juilliard School in New York. His main teacher, and a major influence upon his work, was the Hungarian pianist György Sándor, a student of Bartók. Based in London since 1993, he has pursued an active international career, performing in 24 countries and at most major European venues and festivals. His absolutely vast repertoire of all periods focuses particularly upon music of the 20th and 21st Century. He has given world premieres of over 150 pieces for solo piano, including works by Julian Anderson, Richard Barrett, James Clarke, James Dillon, Pascal Dusapin, Brian Ferneyhough, Michael Finnissy (whose complete piano works he performed in a landmark 6- concert series in 1996), Christopher Fox, Volker Heyn, Hilda Paredes, Horatiu Radulescu, Frederic Rzewski, Howard Skempton, Gerhard Stäbler and Walter Zimmermann. -

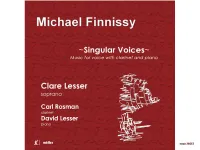

Michael Finnissy Singular Voices

Michael Finnissy Singular Voices 1 Lord Melbourne †* 15:40 2 Song 1 5:29 3 Song 16 4:57 4 Song 11 * 3:02 5 Song 14 3:11 6 Same as We 7:42 7 Song 15 7:15 Beuk o’ Newcassel Sangs †* 8 I. Up the Raw, maw bonny 2:21 9 II. I thought to marry a parson 1:39 10 III. Buy broom buzzems 3:18 11 IV. A’ the neet ower an’ ower 1:55 12 V. As me an’ me marra was gannin’ ta wark 1:54 13 VI. There’s Quayside fer sailors 1:19 14 VII. It’s O but aw ken weel 3:17 Total Duration including pauses 63:05 Clare Lesser soprano David Lesser piano † Carl Rosman clarinet * Michael Finnissy – A Singular Voice by David Lesser The works recorded here present an overview of Michael Finnissy’s continuing engagement with the expressive and lyrical possibilities of the solo soprano voice over a period of more than 20 years. It also explores the different ways that the composer has sought to ‘open-up’ the multiple tradition/s of both solo unaccompanied song, with its universal connotations of different folk and spiritual practices, and the ‘classical’ duo of voice and piano by introducing the clarinet, supremely Romantic in its lyrical shadowing of, and counterpoints to, the voice in Song 11 (1969-71) and Lord Melbourne (1980), and in an altogether more abrasive, even aggressive, way in the microtonal keenings and rantings of the rarely used and notoriously awkward C clarinet in Beuk O’ Newcassel Sangs (1988). -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2001). Interview with Marc Bridle. Seen & Heard, This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/6626/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Interview with Marc Bridle, February 2001 Online at http://www.musicweb-international.com/SandH/2001/Feb01/pace1.htm and http://www.musicweb-international.com/SandH/2001/Feb01/pace2.htm IAN PACE (b.1968) is a leading British pianist, renowned for his transcendental technique and championship of new music in both the UK and Europe, and in recordings. He is currently in the middle of a groundbreaking series of three London recitals attended bySeen&Heard, at the Wigmore Hall, Royal Academy of Music and King's College. In a wide ranging interview with Marc Bridle he discusses his background and musical training, and the egalitarian, anti-nationalist aesthetic and political beliefs which inform his gruelling schedule of varied musical activities, and that led him to seek to present an 'alternative Britain' in his debut CD Tracts recorded in 1997, but which has only now been belatedly released. -

301278 Vol1.Pdf

INTERPRETATIVE ISSUE PERFO CONTEMPORARY PIANO MUSIC J by\ Philip Thomas (Volume I) Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Performance Practice Department of Music University of Sheffield April 1999 SUMMARY This thesis explores practical and theoretical issues in interpreting contemporary notated piano music. Interpretative problems and approaches are discussed with a practical bias, using a varied selection of musical sources mostly from the last fifty years. The diversity of compositional styles and methods over this period is reflected in the diversity of interpretative approaches discussed throughout this thesis. A feature of the thesis is that no single interpretative method is championed; instead, different approaches are evaluated to highlight their benefits to interpretation, as well as their limitations. It is demonstrated how each piece demands its own approach to interpretation, drawing from different methodologies to varying degrees in order to create a convincing interpretation which reflects the concerns of that piece and its composer. The thesis is divided into four chapters: the first discusses the implications and ambiguities of notation in contemporary music; the second evaluates the importance of analysis and its application to performance and includes a discussion of the existing performance practice literature as well as short performer-based analyses of three pieces (Saxton's Piano Sonata, Tippett's Second Piano Sonata, and Feldman's Triadic Memories); the third chapter considers notions of style and performing traditions, illustrating the factors other than analysis that can 'inform' interpretation; and the fourth chapter draws together the processes demonstrated in the previous chapters in a discussion of the interpretative issues raised by Berio's Seguenza IV. -

Program Notes

‘Hear and Now’ Studio Concert Sunday 9 March 2008 7.30pm Studio 1, BBC Broadcasting House, Llandaff, Cardiff Contemporary Music Ensemble of Wales Kenneth Woods conductor Ian Pace piano John Senter cello GORDON DOWNIE Fragments for cello and piano 3’ PAUL MEFANO Interferences – fragments IV,V,VI (UK premiere) 10’ GORDON DOWNIE Piano Piece 3 (Wales premiere) 12’ Interval (15 Minutes) EARLE BROWN Novara 10’ GORDON DOWNIE Forms 7: non-mediated forms for 24 instrumentalists (World premiere) 10’ IANNIS XENAKIS Akrata 12’ This concert will be broadcast on BBC Radio 3’s ‘Hear and Now’ on Saturday 19 March, 2008 at 10.30pm This concert is part of Greece in Britain 2008, a nationwide series of events presented by the Hellenic Foundation for Culture This concert is dedicated to the memory of the writer and new music specialist John Warnaby, who died in January 2007. John, who lived in Port Talbot, was a committed writer and commentator on new music whose contribution to the field will be greatly missed. CMEW acknowledges the financial support of the Arts Council of Wales, the Hinrichsen Foundation and the Hellenic Foundation for Culture. GORDON DOWNIE Paul Mefano received encouragement from Alfred Cortot to study Fragments for cello and piano (1990–2005) music. Later, he studied with Andrée Vaurabourg-Honegger and then at the Conservatoire of Paris with Darius Milhaud and Georges Dandelot. Commissioned by Margaret Reid and Derek Clarke and premiered in He continued his studies with Boulez, Stockhausen and Pousseur in Cardiff, 1990. Basle, attending concerts in the Domain Musical, the Darmstadt summer The majority of Fragments for cello and piano was composed in school and the class of Olivier Messiaen at the C.N.S.M.P In 1965 his 1990.The recent revision and extension in 2005 involved developing and music was performed for the first time under the direction of Bruno re-characterizing certain material.Whilst the earlier material informally Maderna at the Domain Musical. -

CATALOGUE of the WORKS of CHRISTOPHER FOX Further Information from [email protected]

CATALOGUE OF THE WORKS OF CHRISTOPHER FOX Further information from [email protected] Works in chronological order re:play for solo cello with prerecorded soundtrack; for Anton Lukoszevieze. new work for solo soprano with live electronics. Text: Norman Nicholson. Written for Elizabeth Hilliard. From the water for choir (SATB) (3’30”). Texts: St, Matthew’s gospel (chapter 3, verses 1-17) in John Wycliffe’s translation and Henry Vaughan. Commissioned for the 750th anniversary of the founding of Merton College, Oxford; premiere, 2014. The Wedding at Cana (after the Master of the Spanish Kings) for string quartet (c.20′); commissioned by the Sound Festival, Aberdeen; to be premiered by the Edinburgh Quartet in the Sound Festival, Aberdeen, 26 October 2013. suo tormento for vocal consort (SSATB) (6′). Texts by Dante and Gramsci. Commissioned by EXAUDI as part of their Italian Madrigal book; premiere, Wigmore Hall, 6 November 2013. The Dark Roads for voice, viola, keyboard tuned in sixth-tones and sound-files (c.20′). Text by Ian Duhig, commissioned by Trio Scordatura and dedicated to them and to the memory of Horatiu Radulescu; premiere, Tate Britain, 5 April 2013. Two movements, which may also be performed separately, as In the old style and The Dark Road. Tales from Babel for six voices (25′). Text: Edward Wickham. Commissioned by The Clerks with funds from the Wellcome Trust; can be performed separately or as the first part of a two act voice drama of which Roger go to yellow three is the second part. Premiered by The Clerks at the Cheltenham Festival on 7 July 2013. -

Notation, Time and the Performer's Relationship

View metadata,citationandsimilarpapersatcore.ac.uk NOTATION, TIME AND THE PERFORMER’S RELATIONSHIP TO THE SCORE IN CONTEMPORARY MUSIC Ian Pace To Mark Knoop I. THE PERFORMER’S READING OF GRAND NARRATIVES There is a certain narrative construction of Western musical his- tory, concerning development of the composer-performer rela- tionship and the concomitant evolution of musical notation, which is familiar and at least tacitly accepted by many. This nar- rative goes roughly as follows: in the Middle Ages and to a lesser extent to the Renaissance, musical scores provided only a bare out- line of the music, with much to be filled in by the performer or performers, who freely improvising within conventions which were for the most part communicated verbally and were highly specific to region or locality. By the Baroque Era, composers had become more specific in terms of their requirements for pitch, rhythm and articulation, though it was still common for perform- ers to apply embellishments and diminutions to the notated scores; during the Classical Period a greater range of notational specificity was introduced for dynamics and accentuation. All of these developments reflected an increasing internationalisation of music-making, with composers and performers travelling more widely around Europe, whilst developments in printing technol- ogy and its efficiency enabled scores to be more widely distributed throughout the continent. This process necessitated a greater degree of notational clarity, as performers could no longer be relied upon to be cognisant of the performance conventions in the locality in which a work was conceived and/or first performed. With Beethoven comes a new conception of the role of the com- poser, less a servant composing to occasionprovided by at the behest of his feu- brought toyouby City ResearchOnline 151 CORE Ian Pace Notation, Time and the Performer’s Relationship to the Score… dal masters, more a freelance entrepreneur following his own has, at least in some quarters. -

IAN PACE – Piano Recital at City University, London

IAN PACE – Piano Recital at City University, London Friday May 30th, 2014, 7:00 pm CHRISTOPHER FOX, More light (1987-88) The musical ideas of More light are in a continual state of evolution, although the nature and pace of that evolution changes from section to section, and periodically an evolutionary process transforms an idea so radically that it metamorphoses into something new. In a sense the work does not have "material": instead it consists of particular piano sonorities that the processes of the music call into being. More light was written in 1987 and 1988 for Philip Mead, who commissioned it with funds from Northern Arts and premiered it on July 28 1988 in Newcastle Playhouse. The version of More light which Philip Mead played in Newcastle differed from the version recorded here in two respects. In a number of the long pauses the resonance caught by the pedal was reinforced electronically with sustained pitches played through small speakers placed directly under the piano - this proved to be aurally redundant and was immediately dropped. In the second main section of the piece there was some equally redundant over-writing which had to be removed rather more painstakingly. I had conceived this section in a number of contrapuntal layers and had simply written them all into the score without thinking through the muscular trauma I was creating for the pianist's hands, wrists and arms - where the pianist is now asked to play two notes on each demi-semiquaver I originally asked Philip to play three! Being the sort of musician he is he found a way of playing what I had written, but after the premiere he showed me a way of revising the passage which would achieve a much greater fluidity of sound production while retaining the impression of contrapuntal density. -

Basque and Modernist Influences in Gabriel Erkoreka's Works for Solo Piano (1994-2019)

BASQUE AND MODERNIST INFLUENCES IN GABRIEL ERKOREKA'S WORKS FOR SOLO PIANO (1994-2019) Ariel Magno da Costa A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS August 2021 Committee: Laura Melton, Advisor Yuning Fu Graduate Faculty Representative Nora Engebretsen Brian Snow © 2021 Ariel Magno da Costa All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Laura Melton, Advisor The music of Spanish composer Gabriel Erkoreka (b. 1969) has been widely performed in Spain and across Europe, but it has received little attention from performers in the Americas and from scholars worldwide. To the author’s knowledge, only one conference paper has examined a work by Erkoreka in great detail, while two other dissertations include passing mention of his music. The composer has drawn inspiration from his native Basque culture, piano literature from Western Art Music, and modernist techniques and styles, most notably the music of British composer Michael Finnissy (b. 1946). This unique blend has resulted in a style that is authentic and distinct from his contemporaries, while at the same time being rooted in traditional music; it also poses a challenge to analytical methods, since any approach on its own would severely underserve this kind of music. This research document is the first detailed discussion of works for solo piano by Gabriel Erkoreka to date. For a broad discussion of his writing for the instrument, six works were selected: Nubes I (1994), Jaia (2000), Dos Zortzikos (2000), Kaila Kantuz (2004), Mundaka (2009), and Ballade no.