Designing Schools from the Inside Out

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Installation Procedure Fibreguard™ Closure Be Sure to Read and Completely Understand This Procedure Before Applying Product

DECEMBER 2008 Installation Procedure FibreGuard™ Closure Be sure to read and completely understand this procedure before applying product. Be sure to select the proper OCC product before application. Cable Preparation and Installation Express Cable 1. Remove sheaths as per manufacturers’ instructions. (Figure 1) Drop Cable (Cut Cable) Drop Cable Figure 2 CABLE SEALING Express Cable Entry 3. Feed the uncut express buffer tubes and cable butts through the end plate express opening. Express Cable (Continuous Loop) (Figure 3) Figure 3 Express Cable Center Wedge Figure 1 4. Insert the center wedge grommet between the Drop Cable express cables narrow end first with the shape and keys aligned to the opening. Continue Closure Minimum inserting until flush with the end plate (Figure 4) Size Sheath Removal 650 1.93m (76”) Step 1 800 1.93m (76”) 500 1.93m (76”) Express Cable Step 2 Closure Minimum Size Sheath Removal 650 3.86m (152”) 800 3.86m (152”) 500 3.86m (152”) Figure 4 NOTE: Cut cable can utilize the express openings, Sheath Cleaning proceed as described in the following notes 2. Using the cleaning tissue provided, clean and de- except there is no need to cut cable grommets, grease all prepared cable sheaths. (Figure 2) they can be slid over the cable end. 10771801 Rev C 4126 1 Grommet Selection and Fitting Split Grommets 5. Measure the circumference of each express or 6. Express cable grommetswill require splitting. The drop cable entering the closure with the grommet splitting operation can be completed with a clean measure tape to determine which size grommets cut through the grommet material with scissors. -

Pace Final 26.11.15

Positions, Methodologies and Aesthetics in the Published Discourse about Brian Ferneyhough: A Critical Study Ian Pace1 Since Brian Ferneyhough achieved a degree of public recognition following the premiere of his Transit (1972-75) in March 1975 at the Royan Festival, a range of writings on and reviews of his work have appeared on a relatively regular basis. The nature, scope, style, and associated methodologies of these have expanded or changed quite considerably over the course of Ferneyhough's career––in part in line with changes in the music and its realization in performance––but nonetheless one can discern common features and wider boundaries. In this article, I will present a critical analysis of the large body of scholarly or extended journalistic reception of Ferneyhough's work, identifying key thematic concerns in such writing, and contextualizing it within wider discourses concerning new music. Several key methodological issues will be considered, in particular relating to intentionality and sketch study, from which I will draw a variety of conclusions that apply not only to Ferneyhough, but to wider contemporary musical study as well. Early Writings on Ferneyhough The first extended piece of writing about Ferneyhough's work was an early 1973 article by Elke Schaaf2 (who would become Ferneyhough's second wife),3 which deals with Epicycle (1968), Missa Brevis (1969), Cassandra's Dream Song (1970), Sieben Sterne (1970), Firecyle Beta (1969-71), and the then not-yet-complete Transit. Schaaf’s piece already exhibits one of the most -

D4.2 BIC Annual Forum and IAG Meeting

D4.2 BIC Annual Forum and IAG meeting Grant Agreement 258655 number: Project acronym: BIC Project title: Building International Cooperation for Trustworthy ICT: Security, Privacy and Trust in Global Networks & Services Funding Scheme: ICT Call 5 FP7 Project co-ordinator: James Clarke Programme Manager Waterford Institute of Technology Tel: +353-71-9166628 Fax: + 353 51 341100 E-mail: [email protected] Project website http://www.bic-trust.eu address: Revision: Final Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Sixth Framework Programme (2002-2006) Dissemination Level PU Public up to and including Annex III RE Annex IV (IAG meeting minutes) Building International Cooperation for Trustworthy ICT: Security, Privacy and Trust in Global Networks & Services 1st Annual Forum 29th November 2011 Brussels, Belgium BIC Partners BIC is a Coordination Action Project within the European Commission, DG INFSO Unit F5, Trust and Security Jan. 2011—Dec. 2013 http://www.bic-trust.eu Page 2 / 103 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................5 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................6 MISSION AND OBJECTIVES OF THE ANNUAL FORUM ...................................6 AGENDA...............................................................................................................7 RESULTS OF THE ANNUAL FORUM..................................................................8 Panel session 1. Other INCO-related -

Grommets and Grommet Press Frequently Asked Questions

Grommets and Grommet Press Frequently Asked Questions 1. How can I make my grommet press easier to operate? Remove all dies from the press. You should be able to rotate the press handle freely, with minimal resistance. If you do feel resistance, you should lubricate the press moving head with any type of sewing machine oil. Use grease syringe (#AS65) to lubricate the inside of the moving head. If you still feel resistance when turning the press handle, loosen the 2 bolts on the side about one quarter turn each. 2. What is the best way to prolong the life of my grommet cutters and setters? For cutters, use a cutting block topped with our chipboard, #GLC/P. It is recommended for thin, strong fabrics such as silk, and with our large cutters (GL10/C or larger). This provides a cushioned but stable surface for the cutting edge. Fabric will cut cleaner and dies will stay sharper. For setters, keep a thin layer of sewing machine oil on the working surface of the top setting die at all times, including the cone shaped area protruding from the die face and the groove on the root of the cone shape. Use silicone spray (#AS15) on the working surfaces of the top die every 20 grommets to reduce the setting force. Always keep the cutting and setting dies lubricated with sewing machine oil after your job is completed to prevent rust. 3. Do Rowley Company cutting and setting dies fit presses sold by other companies? Unfortunately, our cutting and setting dies are designed to mate with our grommet presses only, and do not fit any other presses. -

Aero Style Review the Outerwear Edition

AERO STYLE REVIEW THE OUTERWEAR EDITION 100 Years of Gentleman’s Clothing What the Brits Wore Aero Leather; In the Beginning The Story of The Highwayman Hard Times meant Great Jackets in USA From the Bookshelf The Label Archives ISSUE THREE A SMALL SELECTION OF AERO LABELS Page by Page: THE CONTENTS 2 100 Years of British Clothing: Saville Row to Scappa Flow No Century brought so many changes to men’s clothing as the nation went through the Class Divide, two World Wars, The General Strike, Rock’n’Roll, Psychedelia, Punk Rock and the re Birth of proper leather jackets in 1981. 6 Aero Leather Clothing: A Series of “Firsts” Classic Leather Jackets, how a small Scottish company led the revolution, bringing back lost tailoring techniques while resurrecting Horsehide as the leather of choice. 8 The Story of The Highwayman: Battersea To Greenbank Mill Perhaps the best known jacket of the last 40 years, how it went from its 1950s inception all the way to the 21st Century and back again, this time to the 1930s. 10 Hard Times but Great Jackets in USA: The Depression Years While the country suffered The Great Depression, Prohibition and The Dust Storms necessity saw the birth of some of the most outstanding jackets of the Century. 12 From the Bookcase: Essential companions for a rainy afternoon A selection of reference books recommended for collectors of vintage clothing covering Vintage Leather Jackets, The USAAF, The CC41 Scheme and Aero Leather Clothing. Cover: Luke Evans wears an Aero “Hudson”. Photo by Gavin Bond. Contents Page: Aero founder Ken Calder. -

Puzzle Book Assembly

My Fair Lady Puzzle Book Assembly Thank you for purchasing designs from My Fair Lady. Please print and read these instructions. CONTENTS: • Supply List • Puzzle Book Assembly • Resources SUPPLY LIST: • My Fair Lady Puzzle Book Designs found at www.myfairladydesigns.com • ¼” grommets 4x4 Book - 39 Grommets 5x7 Book - 65 Grommets • 2-3 yds ribbon (Actual length of ribbon depends on which book you are making and how tightly the book is bound) • Sewing and bobbin thread • Size 80/12 Universal sewing needle • ¼” (or 3/16”) hole punch • Hammer • Setting Mat • Tapestry needle Puzzle Book Assembly These instructions are for a book made from felt, fleece, or fabric that will not fray. If you used something else, you will need to either finish your edges or stitch the pages along three sides, then turn them right side out and finish the last side. 1. Stitch each of the monthly puzzle pages, covers, and tabs. Follow the instructions included in each set. 2. Trim the stabilizer around the design on the back of each page. 3. Place the Front Cover and January Page 1 wrong sides together. 4. Place the tab with the button in between the two pages as shown. The tabs are extra long to accommodate a very thick book. You will want to stack all the pages together (with the accessories in the pockets) and adjust the tabs to the correct length before sewing! 5. Sew the pages together around the edges. Use a ¼” seam allowance. A walk- ing foot is recommended. 6. Place January Page 2 and February Page 1 together, and sew around the edges. -

Gk1238tm Multi-Grommet Tool Kit

GK1238TM MULTI-GROMMET TOOL KIT (A) Hardwood backer (D) Grommet (C) Punch (E) Washer (B) Hole cutter (F) Anvil • For repairing or adding to canvas, tarpaulins, tents, awnings, sailcloth, lawn furniture, pool covers and crafting material • Includes: six-3/8” Brass Grommets, Six-1/2” Brass Grommets, Universal Punch Body with Two Punch Heads (3/8” & 1/2”), Two-sided anvil, two hole punches and wood backer block INSTRUCTIONS STEP 1 STEP 3 Place hardwood backer (A) on work Place Grommet (D) (post up) surface below material you are on anvil (F). Center the hole in material over D fastening. A grommet tube. F STEP 2 STEP 4 Place hole cutter (B) over mark and Place washer (E) rounded strike with a plastic mallet or ball side up tightly over grommet B tube and material. Insert peen hammer. C punch (C) into tube. Strike A firmly with ball peen hammer; E rotate punch ¼” turn D between strikes until F grommet and washer fit tightly to material. The setting tools are not intended for extensive commercial or industrial use. PRODUCT WARNINGS: Wear Safety Goggles. The failure to do so may result in personal injury. The setting tools are not intended for extensive commercial or industrial use. Using them in this manner for an extensive period may result in property damage or personal injury. To avoid personal injury, always wear OSHA/ANSI approved eye protection (goggles, face shield) when using tools. WARNING: This product contains one or more chemicals known to the state of California to cause birth defects and other reproductive harm and/or cancer. -

How to Use Hand Tools to Apply 3/8” Grommets

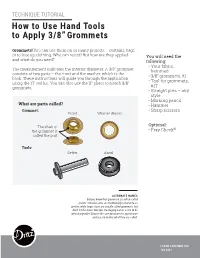

TECHNIQUE TUTORIAL How to Use Hand Tools to Apply 3/8” Grommets Grommets! You can use them on so many projects – curtains, bags or to lace up clothing. Who can resist? But how are they applied You will need the and what do you need? following: • Your fabric, The measurement indicates the interior diameter. A 3/8” grommet hemmed consists of two parts – the front and the washer, which is the • 3/8” grommets, #1 back. These instructions will guide you through the application • Tool for grommets, using the 1T tool kit. You can also use the 1P pliers to attach 3/8” grommets. #1T • Straight pins – any style • Marking pencil What are parts called? • Hammer Grommet: • Sharp scissors Front Washer (Back) The shaft of Optional: ® the grommet is • Fray Check called the post Tools: Setter Anvil ALTERNATE NAMES Did you know that grommets are often called eyelets? Smaller sizes are traditionally referred to as eyelets, while larger sizes are usually called grommets, but don’t let the name fool you. Packaging names seem to be interchangeable! Choose the size you want for appearance and use, no matter what they are called. © PRYM CONSUMER USA July 2021 TECHNIQUE TUTORIAL How to Use Hand Tools to Apply 3/8” Grommets: 1. You have measured your project and placed a pin at each eyelet location. 1. (See the tutorial – “How to Measure for Grommet and Eyelet Placement.”) Now, place a mark at each pin inter- section. 2. Trace around inside opening of 2. grommet post. 3. Use small scissors to cut out marked circle. -

Adittybagapprenticeship

1 A DittyBagApprenticeship EE HOW SHE SCHOONS! Cutting a feather in the various elements upon which its survival Sa four-lower breeze, sails filling in powerful depended was once an absolute necessity, and curves and pulling like the muscles ofa draft horse there were always men aboard capable of handl with a heavy load; sails straining under therelent ing the various materials, not the least ofwhom less force ofthe wind! was the sailmaker. He was not alonein working By moonrise, the wind's diminished to a with canvas; even the greenest hand had to take whisper-hardly a ripple on the water as she up needle and palm when there was extensive ghosts slowly along under light sails; great cloth work to be done. Seafaring people ashore, out of phantoms tranquillybillowing in the moonlight. geographical or economic necessity, had no less a Or in an oily calm, the limp cloth slats andslams need to be self-sufficient in the manufacture and from side to side, awaiting the day when it might repair of the sails for the boats with which they explode from its boltropes under the force of a earned their livelihood. Those Johnny New howling gale and be lashed and beaten to useless combes who'd assist the seagoing sailmaker were 'hreds. Harmony and discord in the marriage of often initiated into the sailor's arts by the making 'ud, wave, wood, and cloth. ofa ditty bag. Those small bags were sometimes Cloth is admirable for bothwhat itis andwhat it elaborately andintricatelyfinished, thus offering a s. First a fiber, spun into thread and woven into means of self-expression and furnishing some workable, versatile, yet vulnerable fabric, cloth is thing to occupy idle hands and to keep the mind ade into sails, the soul and salvation ofthe sailing alive. -

Ventilation Tubes

Ventilation Tubes Ventilation Tubes • All products are sterile, single-use unless otherwise noted • Ventilation Tube Dimensions in millimeters *Order in quantities of 6 tubes or 50 tubes per package. Please indicate a suffix for each order: - 01 (tube per package / 6 sterile packages per dispenser box) - 50 (packages per dispenser box) Measurement Key Material Abbreviation Key A B C D E FP / BL Fluoroplastic/Blue Inner Flange Outer Flange Inter Flange Inner Diameter Total Length FP / W Fluoroplastic/White Diameter Diameter Distance PE / BL Polyethylene/Blue S / BL Silicone/Blue SS Stainless Steel TT Titanium Armstrong Beveled Straight Shank The angle of the beveled inner flange corresponds to the angle of the tympanic membrane for easier insertion, resistance to prema- ture extrusion, and visibility through the lumen. Armstrong Beveled Straight Product No. Feature Material A B C D E Shank VT-0500-* ---- S / BL 1.14 2.6 — 7.0 — VT-0501-* ---- FP / BL 1.14 2.6 — 7.5 — VT-0502-* ---- PE / BL 1.14 2.6 — 7.0 — Armstrong Grommet Beveled inner flange corresponds to the angle of the tympanic membrane for easier insertion, extrusion resistance, and visibility through the lumen. Outer flange adds security. Armstrong Grommet Product No. Feature Material A B C D E VT-0503-* ---- FP / BL 1.14 2.6 2.4 1.0 4.0 VT-0507-* w/Wire FP / BL 1.14 2.5 2.4 1.0 4.0 VT-0509-* ---- PE / BL 1.09 2.5 2.5 1.0 4.3 Modified Armstrong Grommet Modified angle facilitates insertion into the myringotomy. -

Sip & Puff Straw Modified Fabric Masks Created in Response To

Sip & Puff Straw Modified Fabric Masks Created in Response to COVID-19 Prevention Project time: 5 - 10 minutes *Disclaimer: These face masks will Not guarantee the prevention of contracting or spreading COVID-19. Please read the available information regarding masks and how to use them from a credible source (such as CDC.gov) to inform you of “best practices” in using the resource and instructions outlined in this document. Needed Materials for Adapting a Cloth Face Covering / Fabric Mask: Component Price Source Notes Cloth Face Covering / Fabric Mask Materials Instructions adapted from: This links to instructions for cost varies: https://www.unitypoint.org/cedarrap making a fabric face mask ids/filesimages/Coronavirus/Olson%2 based on the Olson Mask $5.00 - 0Mask%20with%20Pattern%20v4.pdf Pattern template by Clayton $20.00 Skousen and Rose Hedges Premade Cloth face coverings can be at UnityPoint Health - Cedar purchased on Amazon, Etsy, or from Rapids. local retailers. Example: https://bekindtoeveryone.com/produ cts/be-kind-to-everyone-face- masks?variant=31757797261427 Grommet Tool Kit $16.15 https://www.amazon.com/Pangda- Grommet kit set includes a Grommet-Setting-Tool- hole cutter, a matched 100+Sets+Grommets+Eyelets+with+St mandrel, and 100 sets of orage+Box-2/5+Inch+Inside+Diameter grommets eyelets (each set includes 1 eyelet and 1 washer), and a storage box; Eyelets size: 2/5” (10 mm) internal hole diameter Silicone Grommet $9.99 https://www.amazon.com/Silicone 40 Silicone Straw Hole Straw Hole Grommets with Attached Grommets with -

U.S. Flags Are Made the Same

U.S. OUTDOOR FLAGS 100% AMERICAN MADE! A SUPERIOR NYLON FLAG FABRIC SECOND TO NONE Strength. Durability. Visibility. SolarMax® fabrics are tough, durable and long-lasting. We use SolarMax® • Fabric designed specifically for • High resistance to UV fading for all nylon flags active outdoor use • Deeper, brighter colors that will last in this catalog. • Tremendous strength retention over time under UV exposure • Better wash-fastness and light- • World-class tensile and tear strength fastness than other nylons of similar • Increased overall performance fabric construction SolarMax® is a registered trademark of INVISTA for UV resistant fibers and fabrics. NOT ALL U.S. FLAGS ARE MADE THE SAME. DOES YOUR CURRENT FLAG SUPPLIER OFFER ALL OF OUR FEATURES? FLY END FEATURES HEADER FEATURES Header Stitching 12" x 18" HEADERS: All headers are made with a heavy-duty, ▪ Fly Stitching: 2 rows bright white cotton polyester blend army duck cloth. ▪ Fold: 3/8" double ▪ Stripe Stitching: no GROMMETS: All grommets are solid brass. #1 Brass Grommet ▪ Corner: back-tacked 1/2" Grommets are spaced evenly throughout the length of the header. #1 flat rimmed grommets are used 12" X 18" to 6' x 10' for 12" x 18" flags. #2 rolled rimmed grommets with a tooth washer are used for all 16" x 24" and larger flags. 8' x 12' and larger include a heavy-duty plastic 16" x 24" through 5' x 9-1/2' reinforcement sleeve at each grommet location. ▪ Fly Stitching: 4 rows ▪ Fold: 1" double ROPE THIMBLE: #10 white nylon rope is sewn #2 Brass Grommet ▪ Stripe Stitching: 3-1/2" double on into the header.