Three Puzzles from Early Nineteenth Century Arctic Exploration C. Ian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aboriginal Rights and the Canadian Constitution, by Michael Asch

REVIEWS 157 DR JOHN RAE. By R.L. RICHARDS. Whitby: Caedmon of Whitby (9 The sixmaps are helpful, but they omit a few of the important place John Street, Whitby, England YO21 3ET), 1985.231 p. +6 maps, namesmentioned in the text. An additionaloverall map of the 31 illus., bib., index. f16.50. Franklii search expeditions would have been helpful. Richards made animportant geographical error on page 44: Theone-mile-wide John Rae was one of the most successful arctic explorers. His four isthmus seen byRae joined the Ross Peninsula, not the Penin- majorexpeditions mapped, by his reckoning, 1765 miles of pre- Boothia viously unknown arctic coastline. He proved that Boothia was a penin-sula as stated. I would have liked more detailed references in the names sula and that King William Land was an island. He was the first to already numerous footnotes, indexing of important that appear only in footnotes, and a list of the maps and illustrations. Richards obtain definitive evidence regarding the fate of the third Franklin fails to mention that modern Canadian maps and the officialGazeteer exetion. give inadequate credit to Rae, sometimes giving his names to the Rae was prepared for his later achievements by his childhood in thewrong localities and misspelling Locker for LockyerWdbank and for Orkneys and by ten years with the Hudson’s Bay Company at MooseWelbank. One of Rae’s presentations to the British Association has Factory. Of his Orkney activities Rae later said: been omitted. In a few places it would have been helpfulto have given By the time I was fifteen, I had become so seasoned as to care little modern names of birds and mammals (Rae’s “deer” are of course about cold or wet, had acquired a fair knowledge of boating, was a caribou). -

ARCTIC Exploration the SEARCH for FRANKLIN

CATALOGUE THREE HUNDRED TWENTY-EIGHT ARCTIC EXPLORATION & THE SeaRCH FOR FRANKLIN WILLIAM REESE COMPANY 409 Temple Street New Haven, CT 06511 (203) 789-8081 A Note This catalogue is devoted to Arctic exploration, the search for the Northwest Passage, and the later search for Sir John Franklin. It features many volumes from a distinguished private collection recently purchased by us, and only a few of the items here have appeared in previous catalogues. Notable works are the famous Drage account of 1749, many of the works of naturalist/explorer Sir John Richardson, many of the accounts of Franklin search expeditions from the 1850s, a lovely set of Parry’s voyages, a large number of the Admiralty “Blue Books” related to the search for Franklin, and many other classic narratives. This is one of 75 copies of this catalogue specially printed in color. Available on request or via our website are our recent catalogues: 320 Manuscripts & Archives, 322 Forty Years a Bookseller, 323 For Readers of All Ages: Recent Acquisitions in Americana, 324 American Military History, 326 Travellers & the American Scene, and 327 World Travel & Voyages; Bulletins 36 American Views & Cartography, 37 Flat: Single Sig- nificant Sheets, 38 Images of the American West, and 39 Manuscripts; e-lists (only available on our website) The Annex Flat Files: An Illustrated Americana Miscellany, Here a Map, There a Map, Everywhere a Map..., and Original Works of Art, and many more topical lists. Some of our catalogues, as well as some recent topical lists, are now posted on the internet at www.reeseco.com. -

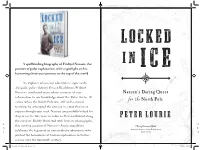

Locked in Ice: Parts

Locked in A spellbinding biography of Fridtjof Nansen, the Ice pioneer of polar exploration, with a spotlight on his harrowing three-year journey to the top of the world. An explorer who many adventurers argue ranks alongside polar celebrity Ernest Shackleton, Fridtjof Nansen contributed tremendous amounts of new Nansen’s Daring Quest information to our knowledge about the Polar Arctic. At North Pole a time when the North Pole was still undiscovered for the territory, he attempted the journey in a way that most experts thought was mad: Nansen purposefully locked his PETER LOURIE ship in ice for two years in order to float northward along the currents. Richly illustrated with historic photographs, -1— —-1 Christy Ottaviano Books 0— this riveting account of Nansen's Arctic expedition —0 Henry Holt and Company +1— celebrates the legacy of an extraordinary adventurer who NEW YORK —+1 pushed the boundaries of human exploration to further science into the twentieth century. 3P_EMS_207-74305_ch01_0P.indd 2-3 10/15/18 1:01 PM There are many people I’d like to thank for help researching and writing this book. First, a special thank- you to Larry Rosler and Geoff Carroll, longtime friends and wise counselors. Also a big thank- you to the following: Anne Melgård, Guro Tangvald, and Jens Petter Kollhøj at the National Library of Norway in Oslo; Harald Dag Jølle of the Norwegian Polar Institute, in Tromsø; Karen Blaauw Helle, emeritus professor of physiology, Department of Biomedicine, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway; Carl Emil Vogt, University of Oslo and the Center for Studies of Holocaust and Religious Minorities; Susan Barr, se nior polar adviser, Riksantikvaren/Directorate for Cultural Heritage; Dr. -

England's Search for the Northern Passages in the Sixteenth And

- ARCTIC VOL. 37, NO. 4 (DECEMBER 1984) P. 453472 England’s Search for the Northern Passages in the Sixteenth and. Early Seventeenth Centuries HELEN WALLIS* For persistence of effort in the. face of adversity no enterprise this waie .is of so grete.avantage over the other navigations in in thehistory of exploration wasmore remarkable than shorting of half the waie, for the other must.saileby grete cir- England’s search for the northern passages to the Far East. .cuites and compasses and .thes shal saile by streit wais and The inspiration for the search was the hope of sharing in the lines” (Taylor, 1932:182). The dangerous part of the.naviga- riches of oriental commerce. In the tropical.regions of the Far tion was reckoned.to .be the last 300 leagues .before reaching East were situated, Roger Barlow wrote in 1541, “the most the Pole and 300 leagues beyond it (Taylor, 1932:181). Once richest londes and ilondes in the the worlde, for all the golde, over the Polethe expedition would choose whetherto sail east- spices, aromatikes and pretiose stones” (Barlow, 1541: ward to the Orient by way of Tartary or westward “on the f”107-8; Taylor, 1932:182). England’s choice of route was backside ofall the new faund land” [NorthAmerica]. limited, however, by the prior discoveries of .Spain and Por- Thorne’s confident .opinion that“there is no lande inhabitable tugal, who by the Treatyof Tordesillas in 1494 had divided the [i.e. uninhabitable€, nor Sea innavigable” (in Hakluyt, 1582: world between them. With the “waie ofthe orient” and ‘The sig.DP) was a maxim (as Professor.Walter Raleigh (19O5:22) waie of the occydent” barred, it seemed that Providence had commented) “fit to be inscribed as a head-line on the charter especially reserved for England. -

The North Pole: a Narrative History

THE NORTH POLE: A NARRATIVE HISTORY EDITED BY ANTHONY BRANDT NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC ADVENTURE CLASSICS WASHINGTON, D.C. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION BY ANTHONY BRANDT ix PART ONE LOOKING NORTH I DIONYSE SETTLE JO A True Report of Captain Frobisher, His Last Voyage into the West and Northwest Regions, 1577 JOHN DAVIS 20 The Second Voyage Attempted by Master John Davis, 15S6 . GERRIT DE VEER 28 The True and Perfect Description of Three Voyages, So Strange and Wonderful, etc., l6ocj ABACUK PRICKETT 41 A Larger Discourse of the Same Voyage. ..1610 PART TWO SEARCH FOR THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE REVIVED 56 WILLIAM SCORESBY 64 A Voyage to the Whale Fishery, l822 JOHN ROSS 78 A Voyage of Discovery Made Under the Orders of the Admiralty, l8ig WILLIAM EDWARD PARRY 87 Journal of a Voyage for the Discovery of a North-West Passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific l8ig-2O JOHN FRANKLIN 106 Narrative of a Journey to Shores of the Polar Sea VIII THE NORTH POLE: A NARRATIVE HISTORY JOHN RICHARDSON 123 Arctic Ordeal: The Journal of John Richardson GEORGE F. LYON 134 The Private Journal of George F. Lyon of the H.M.S. Hecla, 1824 ROBERT HUISH 157 The Last Voyage of Capt. Sir John Ross to the Arctic Regions, for the Discovery of a Northwest Passage, 1823-1833 ROBERT R. CARTER 168 Private Journal of a Cruise in the Brig Rescue in Search of John Franklin JOHN RAE 188 Correspondence with the Hudson's bay Company on Arctic Exploration, l844~l&55 LEOPOLD MCCLINTOGK 202 The Voyage of the Fox in the Arctic Seas PART THREE To THE TOP OF THE WORLD 226 ELISHA KENT KANE 229 Arctic Explorations: The Second Grinnell Expedition in Search of Sir John Franklin CHARLES FRANCIS HALL 251 Life with the Esquimaux EUPHEMIA VALE BLAKE 268 Arctic Experiences: Containing Capt. -

Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

A University of Sussex MPhil thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the aut hor, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details THE MEANING OF ICE Scientific scrutiny and the visual record obtained from the British Polar Expeditions between 1772 and 1854 Trevor David Oliver Ware M.Phil. University of Sussex September 2013 Part One of Two. Signed Declaration I hereby declare that this Thesis has not been and will not be submitted in whole or in part to another University for the Award of any other degree. Signed Trevor David Oliver Ware. CONTENTS Summary………………………………………………………….p1. Abbreviations……………………………………………………..p3 Acknowledgements…………………………………………….. ..p4 List of Illustrations……………………………………………….. p5 INTRODUCTION………………………………………….……...p27 The Voyage of Captain James Cook. R.N.1772 – 1775..…………p30 The Voyage of Captain James Cook. R.N.1776 – 1780.…………p42 CHAPTER ONE. GREAT ABILITIES, PERSEVERANCE AND INTREPIDITY…………………………………………………….p54 Section 1 William Scoresby Junior and Bernard O’Reilly. Ice and the British Whaling fleet.………………………………………………………………p60 Section 2 Naval Expeditions in search for the North West passage.1818 – 1837...........……………………………………………………………..…….p 68 2.1 John Ross R.N. Expedition of 1818 – 1819…….….…………..p72 2.2 William Edward Parry. -

The Opening of the Transpolar Sea Route: Logistical, Geopolitical, Environmental, and Socioeconomic Impacts

Marine Policy xxx (xxxx) xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Marine Policy journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/marpol The opening of the Transpolar Sea Route: Logistical, geopolitical, environmental, and socioeconomic impacts Mia M. Bennett a,*, Scott R. Stephenson b, Kang Yang c,d,e, Michael T. Bravo f, Bert De Jonghe g a Department of Geography and School of Modern Languages & Cultures (China Studies Programme), Room 8.09, Jockey Club Tower, Centennial Campus, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong b RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, USA c School of Geography and Ocean Science, Nanjing University, Nanjing, 210023, China d Jiangsu Provincial Key Laboratory of Geographic Information Science and Technology, Nanjing, 210023, China e Collaborative Innovation Center for the South Sea Studies, Nanjing University, Nanjing, 210023, China f Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK g Graduate School of Design, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA ABSTRACT With current scientifc models forecasting an ice-free Central Arctic Ocean (CAO) in summer by mid-century and potentially earlier, a direct shipping route via the North Pole connecting markets in Asia, North America, and Europe may soon open. The Transpolar Sea Route (TSR) would represent a third Arctic shipping route in addition to the Northern Sea Route and Northwest Passage. In response to the continued decline of sea ice thickness and extent and growing recognition within the Arctic and global governance communities of the need to anticipate -

Giles Land—A Mystery for S.A. Andrée and Other Early Arctic Explorers Björn Lantz

RESEARCH ARTICLE Giles Land—a mystery for S.A. Andrée and other early Arctic explorers Björn Lantz Technology Management and Economics, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden Abstract Keywords Kvitøya; Andrée expedition; After the initial discovery of Giles Land (Kvitøya, Svalbard) by Cornelis Giles Arctic exploration; Svalbard; maps in 1707, it was most likely never seen by anyone again until 1876. During this lengthy period, Giles Land evolved into an enigma as various explorers Correspondence and cartographers came to very different conclusions about its probable loca- Björn Lantz, Technology Management tion, character or even existence. In 1897, when the engineer Salomon August and Economics, Chalmers University of Andrée tried to return over the ice after his failed attempt to reach the North Technology, 412 96 Gothenburg, Sweden. Pole in a balloon, he passed through an area approximately 160 km north of E-mail: [email protected] Kvitøya where Giles Land was indicated on his map. Andrée searched for it, but Supplementary material there was no land in sight. The main reason why Giles Land was erroneously To access the supplementary material, positioned too far north was a conjecture by a German cartographer August please visit the article landing page. Petermann in 1872. While there was some distrust of Petermann’s conjecture at the time, many also believed it. The erroneous understanding that Giles Land was located far north of Kvitøya was only finally dismissed in the 1930s. This article examines how this misunderstanding regarding the identity and location of Giles Land could arise and become entrenched. Introduction impossible to reach for almost 170 years after its initial discovery. -

REVIEWS 163 Sherman's Whaling Logbooks and Journals 1613

REVIEWS 163 Sherman's Whaling logbooks and journals 1613-1927 at 493 pages, is just that. It eclipses the Cambridge gives the locations of several thousand manuscripts in illustrated history of archaeology by 107 pages, and rivals public collections as the basis for yet more research. even the massive Oxford companion to archaeology, at A major blank is the lack of information on the trading 864 pages. This is especially remarkable given that of whale products and the methods of processing and underwater and maritime archaeology have existed as manufacture, but I am sure when fragments can be brought recognized subfields of archaeology for little more than together from a huge miscellany of sources in England and three decades. Scotland this can be rectified. Most recently, Alex Buchan Yet the length and coverage of this new attempt to has been delving deep into Peterhead's maritime history, wrestle underwater archaeology into some manageable and Tony Barrow, with a series of papers derived from an framework is not undeserved. Underwater archaeology is unpublished doctoral thesis on Newcastle whaling, is the great leveller amongst all the fields and arcane theory revealing many of the cross-connections of vessels and of archaeology. No subfield cuts across so many time manpower between whaling ports. periods, so many techno-cultural expressions, so many Jones is to be congratulated on his tenacious work at the geographies. Someone calling himself an underwater or 'coal-face,' which, although seldom exciting in itself, is maritime archaeologist can as easily be found studying a rewarding in the end for the very reason that the results are sphinx of the sunken city of Alexandria from two millenia so useful. -

Science and the Canadian Arctic, 181 8-76, from Sir John Ross to Sir

ARCTIC VOL. 41, NO. 2 (JUNE 19W)P. 127-137 Science and the Canadian Arctic, 1818-76, from Sir John Ross to Sir George Strong Nares TREVOR H. LEVERE’ (Received 14 July 1986; accepted in revised form 3 February 1988) ABSTRACT. Nineteenth-century explorationof the Canadian Arctic, primarily directedby the British Admiralty, had scientific as well as geographical goals. Many expeditions, including Franklin’s, had a major scientific mandate. A northwest passage was the initial inspiration, but geomagnetism (under Edward Sabine’s guidance), meteorology, zoology, geology, botany, and ethnology were the principal sciences that benefited. The Royal Society of London, with its Arctic Committee, was closely involved with the Admiralty in recommending scientific programs and in nominating observers to the expeditions. Naval officers too were much concerned with science; some, including Parry and James Ross, were electedof the fellows Royal Society of London (F.R.S.). From John Ross through Parry to Franklin, scientific arctic voyages were strongly promoted. Geomagnetism, natural history, and meteorology were particularly prominent. During the searches for Franklin, the life sciences, geology, and meteorology continued to benefit, while geophysical researches were relatively neglected. After the Franklin disaster, geographical and other scientific exploration languished until the example of other nations and domestic lobbying persuaded the British government to send Nares north in1875-76. This was the last of the old-style scientific expeditions to the Canadian Arctic. Afterwards, co-operation in science (as in the International Polar Year) and concern for the Arctic as national territory became dominant factors in arctic exploration. Key words: science, history, Canada, geomagnetism, natural history, geology, J. -

After the Arctic Sublime

$IWHUWKH$UFWLF6XEOLPH %HQMDPLQ0RUJDQ 1HZ/LWHUDU\+LVWRU\9ROXPH1XPEHU:LQWHUSS $UWLFOH 3XEOLVKHGE\-RKQV+RSNLQV8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV )RUDGGLWLRQDOLQIRUPDWLRQDERXWWKLVDUWLFOH KWWSVPXVHMKXHGXDUWLFOH Access provided by University of Virginia Libraries & (Viva) (25 Jul 2016 14:54 GMT) After the Arctic Sublime Benjamin Morgan an the temperature be interpreted? Consider, for a mo- ment, the meteorological tables published in William Scoresby’s Cpopular Arctic voyage narrative, An Account of the Arctic Regions (1820), which record a minimum temperature of 10 degrees Fahrenheit on April 10, 1810; 15 degrees on the eleventh; 14 on the twelfth—and so on for 1810 through 1818.1 It might be said that these tables mark a hermeneutic boundary. In the wake of new historicism and cultural studies, literary scholars commonly read maritime voyage narratives like Scoresby’s, but we rarely attend to the scientific data they contain. In itself, this is not a surprise. The interpretive challenge presented by such a table is readily apparent: as an index of atmospheric conditions that are not human-made, its meaning seems to lie beyond the realm of humanistic inquiry. Its symbolic register is numerical rather than linguistic, and therefore only minimally explicable in terms of trope, form, rhetoric, or poetics. So, by contrast with Scoresby’s eventful nar- ratives of Arctic adventure and depictions of whaling life, which can be readily interpreted as conveying and sustaining ideologies of national- ity or gender, a table of weather data gestures toward an extracultural beyond. Exactly insofar as it means what it says, Scoresby’s record of the temperature touches upon one limit of symptomatic interpretation. This essay proposes that features like Scoresby’s table, consisting of scientific data, constitute a particularly important site of inquiry within our present critical context and geohistorical moment. -

Arctic Samples

ch01_Robinson_4567.qxd 8/3/06 9:40 AM Page 15 CHAPTER 1 Reconsidering the Theory of the Open Polar Sea M ICHAEL F. ROBINSON n 1845, British explorer Sir John Franklin and a party of 129 men van- ished in the Arctic. The party’s disappearance was a blow to the British I Admiralty and its efforts to discover the Northwest Passage. Yet finding Franklin became the new object of Arctic exploration, a project that piqued popular interest in Great Britain and the United States, and launched dozens of rescue expeditions on both sides of the Atlantic. The search for Franklin also kindled new interest in an old idea, the theory of the open polar sea. Since the Renaissance, geographers had suggested that the high Arctic regions might be free of ice. As the mystery of the Franklin Party deepened, many seized upon the theory as a way of explaining where Franklin might have gone and, more importantly, why he might still be alive. The expedition had become trapped in the open polar sea, they argued, and now sailed its boun- tiful waters searching for a way out. This explanation came at an opportune moment for U.S. and British explorers, who used it to justify new Arctic ex- peditions for a decade after Franklin’s departure. Historians have not been kind to proponents of the open polar sea the- ory, viewing them as wishful thinkers at best and unscrupulous schemers at worst. “The myth of the open polar sea exerted an enormous influence on the Franklin search,” argues L.