Acitretin for Hypertrophic Lichen Planus Like Reaction in a Burn Scar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Review of the Evidence for and Against a Role for Mast Cells in Cutaneous Scarring and Fibrosis

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review A Review of the Evidence for and against a Role for Mast Cells in Cutaneous Scarring and Fibrosis Traci A. Wilgus 1,*, Sara Ud-Din 2 and Ardeshir Bayat 2,3 1 Department of Pathology, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA 2 Centre for Dermatology Research, NIHR Manchester Biomedical Research Centre, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery Research, University of Manchester, Manchester M13 9PT, UK; [email protected] (S.U.-D.); [email protected] (A.B.) 3 MRC-SA Wound Healing Unit, Division of Dermatology, University of Cape Town, Observatory, Cape Town 7945, South Africa * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-614-366-8526 Received: 1 October 2020; Accepted: 12 December 2020; Published: 18 December 2020 Abstract: Scars are generated in mature skin as a result of the normal repair process, but the replacement of normal tissue with scar tissue can lead to biomechanical and functional deficiencies in the skin as well as psychological and social issues for patients that negatively affect quality of life. Abnormal scars, such as hypertrophic scars and keloids, and cutaneous fibrosis that develops in diseases such as systemic sclerosis and graft-versus-host disease can be even more challenging for patients. There is a large body of literature suggesting that inflammation promotes the deposition of scar tissue by fibroblasts. Mast cells represent one inflammatory cell type in particular that has been implicated in skin scarring and fibrosis. Most published studies in this area support a pro-fibrotic role for mast cells in the skin, as many mast cell-derived mediators stimulate fibroblast activity and studies generally indicate higher numbers of mast cells and/or mast cell activation in scars and fibrotic skin. -

Fundamentals of Dermatology Describing Rashes and Lesions

Dermatology for the Non-Dermatologist May 30 – June 3, 2018 - 1 - Fundamentals of Dermatology Describing Rashes and Lesions History remains ESSENTIAL to establish diagnosis – duration, treatments, prior history of skin conditions, drug use, systemic illness, etc., etc. Historical characteristics of lesions and rashes are also key elements of the description. Painful vs. painless? Pruritic? Burning sensation? Key descriptive elements – 1- definition and morphology of the lesion, 2- location and the extent of the disease. DEFINITIONS: Atrophy: Thinning of the epidermis and/or dermis causing a shiny appearance or fine wrinkling and/or depression of the skin (common causes: steroids, sudden weight gain, “stretch marks”) Bulla: Circumscribed superficial collection of fluid below or within the epidermis > 5mm (if <5mm vesicle), may be formed by the coalescence of vesicles (blister) Burrow: A linear, “threadlike” elevation of the skin, typically a few millimeters long. (scabies) Comedo: A plugged sebaceous follicle, such as closed (whitehead) & open comedones (blackhead) in acne Crust: Dried residue of serum, blood or pus (scab) Cyst: A circumscribed, usually slightly compressible, round, walled lesion, below the epidermis, may be filled with fluid or semi-solid material (sebaceous cyst, cystic acne) Dermatitis: nonspecific term for inflammation of the skin (many possible causes); may be a specific condition, e.g. atopic dermatitis Eczema: a generic term for acute or chronic inflammatory conditions of the skin. Typically appears erythematous, -

Advances in Seborrheic Keratosis

A CME/CE-Certified Supplement to Original Release Date: December 2018 Advances in Seborrheic Expiration Date: December 31, 2020 Estimated Time To Complete Activity: 1 hour Participants should read the activity information, Keratosis review the activity in its entirety, and complete the online post-test and evaluation. Upon completing this activity as designed and achieving a passing score on FACULTY the post-test, you will be directed to a Web page that will Joseph F. Fowler Jr, MD Michael S. Kaminer, MD allow you to receive your certificate of credit via e-mail Clinical Professor and Director Associate Clinical Professor of Dermatology or you may print it out at that time. Contact and Occupational Yale Medical School The online post-test and evaluation can be accessed Dermatology New Haven, Connecticut at http://tinyurl.com/SebK2018. University of Louisville School of Adjunct Assistant Professor of Medicine Medicine (Dermatology), Warren Alpert Medical School Inquiries about continuing medical education (CME) Louisville, Kentucky of Brown University accreditation may be directed to the University of Providence, Rhode Island Louisville Office of Continuing Medical Education & Professional Development (CME & PD) at cmepd@ louisville.edu or (502) 852-5329. Designation Statement eborrheic keratosis (SK) has been called keratinizing surface.12 They can develop virtually The University of Louisville School of Medicine the “Rodney Dangerfield of skin lesions”— anywhere except for the palms, soles, and mucous designates this Enduring material for a maximum of 9 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should it earns little respect (as a clinical concern) membranes, but are most commonly observed claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of Sbecause of its benignity, commonality, usual on the trunk and face.6,13 The tendency to develop their participation in the activity. -

Linear Scleroderma “En Coup De Sabre” Coexisting with Plaque-Morphea

661 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.74.5.661 on 1 May 2003. Downloaded from SHORT REPORT Linear scleroderma “en coup de sabre” coexisting with plaque-morphea: neuroradiological manifestation and response to corticosteroids I Unterberger, E Trinka, K Engelhardt, A Muigg, P Eller, M Wagner, N Sepp, G Bauer ............................................................................................................................. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003;74:661–664 progression of skin lesions or any neurological abnormalities A 24 year old woman in the 33rd week of pregnancy during follow up. developed progressive neurological complications with On admission the patient was in the 33rd week of right sided hemiparesis in association with the occurrence pregnancy. She was fully oriented, had normal speech, and of linear scleroderma “en coup de sabre” (LSCS) and pre- presented with a right sided hemiparesis (grade 3/5, MRC existing plaque-morphea, already being treated by scale) with a positive Babinski sign on the right. There was no balneophototherapy. Further progression of neurological history of head trauma. symptoms led to a caesarean section with the delivery of a Routine laboratory testing and comprehensive serological healthy child. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) screening including antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies showed focal T2 signal increases in the left frontoparietal (ANCA), anticardiolipin antibodies, and antibodies against region directly adjacent to the area of LSCS. -

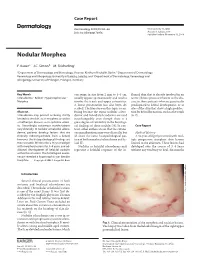

Nodular Morphea

Case Report Dermatology 2009;218:63–66 Received: July 13, 2008 DOI: 10.1159/000173976 Accepted: July 23, 2008 Published online: November 13, 2008 Nodular Morphea a b c F. Kauer J.C. Simon M. Sticherling a b Department of Dermatology and Venerology, Vivantes Klinikum Neukölln, Berlin , Department of Dermatology, c Venerology and Allergology, University of Leipzig, Leipzig , and Department of Dermatology, Venerology and Allergology, University of Erlangen, Erlangen , Germany Key Words can range in size from 2 mm to 4–5 cm, flamed skin that is already involved in an -Scleroderma ؒ Keloid ؒ Hypertrophic scar ؒ usually appear spontaneously and tend to active fibrotic process inherent to the dis Morphea involve the trunk and upper extremities. ease in those patients who are genetically A linear presentation has also been de- predisposed to keloid development, or at scribed. The literature on this topic is con- sites of the skin that show a high predilec- Abstract fusing because the terms ‘nodular sclero- tion for keloid formation, such as the trunk Scleroderma may present as being strictly derma’ and ‘keloidal scleroderma’ are used [6, 7] . limited to the skin, as in morphea, or within interchangeably even though there is a a multiorgan disease, as in systemic sclero- great degree of variability in the histologi- sis. Accordingly, cutaneous manifestations cal findings of these nodules [4] . In con- C a s e R e p o r t vary clinically. In nodular or keloidal sclero- trast, other authors stress that the cutane- derma, patients develop lesions that are ous manifestations may vary clinically, but Medical History clinically indistinguishable from a keloid; all share the same histopathological pat- A 16-year-old girl presented with mul- however, the histopathological findings are tern of both morphea/scleroderma and ke- tiple progressive morpheic skin lesions more variable. -

Stratamark Is Clinically Proven to Prevent and Treat Stretch Marks

Stratamark is clinically proven to prevent and treat stretch marks • Over 500 pregnant women have participated in clinical studies with Stratamark.10,11 • Stratamark is suitable for pregnant women, breastfeeding mothers, children and people with sensitive skin.10,11 The breakthrough medical product for the prevention and treatment of stretch marks • Softens and flattens raised and depressed stretch marks Prevention studies Treatment studies • Reduces redness and discoloration of stretch marks The breakthrough Stratamark group • Relieves itching and discomfort of stretch marks • Suitable for pregnant women, breastfeeding mothers, medical product for children and people with sensitive skin the prevention and 80% of women demonstrated a significant level of improvement in treatment of 18.2% their stretch marks Stratamed and Strataderm help mothers to get the best possible scar outcome after a caesarean section. stretch marks Control group 91% of patients rated the ease of use of Stratamark 60–70% very good - excellent 90% of patients rated the efficacy of use 81.8% of Stratamark did not develop www.stratamed.com www.strataderm.com very good - excellent stretch marks10 Stratamed promotes faster wound healing Strataderm – for the professional treatment and prevents abnormal scarring. of scars both old and new. 87% During wound healing After wound healing (suture removal) of patients rated • Promotes faster wound healing by creating • For effective management of abnormal and Incidence of the feeling on Striae -43% a moist wound healing environment excessive scar formation p < 0.001 the skin to be 80% • Suitable for breastfeeding mothers very good - excellent • Suitable for breastfeeding mothers 60% 40% 61 % 66% of patients in the www.stratamark.net 20% treatment group reduced the severity References: 1. -

Advising Customers About Scars and Stretch Marks

Advising customers about scars and stretch marks Created with help from Supported by expert Pharmacist Deborah Evans FFRPS FRPharmS FRSPH What customers might be looking for advice? According to a recent survey of pharmacists1, pregnant women, new mums and young women are the customers who most often ask them for advice on scarring and stretch marks, however, any of the following groups may seek your help. • Pregnant women and new mums: • Post-operative patients: Not all patients Between 50-90% of pregnant women will will receive advice on scar care when they develop stretch marks, usually in the latter have an operation so they may pop into half of the pregnancy. Women may be their local pharmacy to find out what they looking for advice to help prevent them from can do to reduce any scarring left by a occurring or ways to reduce the appearance surgical procedure. of existing ones. New mums may also have a scar from a C-section delivery. • People with a burn, cut or scrape: Minor skin damage is unlikely to leave a • Teenagers with stretch marks: scar but even fairly small cuts and burns Stretch marks occur when the body is may leave behind a mark. subjected to rapid periods of growth or weight gain. They can commonly develop • People with acne or chicken pox: during puberty growth spurts or when Both can cause depressed scars, breasts develop. called atrophic scars, which can be hard to reduce the appearance of. • Weight loss customers: Following a period of weight loss, customers may be looking for ways to reduce any stretch marks left on their skin. -

Scleroderma Education Program Chapter 7 Heart, Lungs and Kidneys

Scleroderma Education Program Chapter 7 Heart, Lungs and Kidneys Chapter 7- 1 Chapter Highlights 1. Heart Disease in Scleroderma -What the heart does -What can go wrong 2. Lung Disease in Scleroderma -What the lungs do -What can go wrong – symptoms of lung disease 3. Kidney/Renal Disease in Scleroderma -What the kidneys do -What can go wrong This seventh chapter usually takes about 15 minutes. Chapter 7- 2 Remember: Many of the things discussed in this chapter are scary. No one with Scleroderma will have all or even most of the problems described in this manual. We want to include most of the problems that could develop in Scleroderma so that all patients will feel informed. It’s important to discuss your concerns with your doctor. Heart Disease in Scleroderma Who Develops Heart Disease Many people with Scleroderma do not develop heart disease. Some do. If there is a problem with the heart, the person with Scleroderma may be totally unaware of it at first. That's because there are usually no symptoms of heart disease in the early stages of Scleroderma. Doctors use tests to find out if the heart has been affected. What the Heart Does The heart pumps blood to the body and to the lungs The circulatory system is made up of 2 parts: 1. Circulation to the body (Systemic) This part sends blood to the body and oxygen to the organs 2. Circulation to the lungs - (Pulmonary) This part sends blood to the lungs to get oxygen. The heart has 4 chambers: - 2 upper chambers (atria). -

Liquid Nitrogen Treatment Fact Sheet

University of California, Berkeley 2222 Bancroft Way Berkeley, CA 94720 Appointments 510/642-2000 Online Appointment www.uhs.berkeley.edu LIQUID NITROGEN TREATMENT FACT SHEET Application of liquid nitrogen is often used to treat skin lesions such as warts, molluscum and keratoses. Although the exact mechanism of action is unclear, freezing damages the treated lesion preventing its survival. Treatment rarely requires anesthesia and almost never leaves a scar. What to expect f Liquid nitrogen is applied to the top of the skin lesion. Freezing occurs throughout the area which extends slightly to the surrounding tissue. Freezing can cause a stinging, burning pain that peaks about 2 minutes after the treatment is performed. f Within minutes after freezing, surrounding skin will become red and begin to swell. In most cases a blister will actually form within 3-6 hours. Often there is a small amount of bleeding into the blister which will turn it dark purple of black. This is expected and should not be cause for concern. f The blister usually flattens in 2-3 days and sloughs off in 2-4 weeks. How to care for the treated area f As the blister may be tender for the first few days, you may want to protect it with a band-aid. However, most often it may be left to the air. f In most cases the blister top is a good natural bandage which protects the new skin growing underneath. Attempts to remove the blister before the new skin is ready may produce scarring or infection. f Do not soak treated area (ie, wash dishes, swim, etc) during the first 24 hours. -

Time (And Care) Heals All Wounds

Time (and Care) Heals All Wounds I'm just very self-conscious about these scars. They remind me ofthe terrible acne I had as a teenager. -Ellen, 35, social worker f you live a full, active life it is impossible not to I acquire a few scars. Some of us see them as badges of honor. Some of us are simply embarrassed by them. How we feel about our scars often has a lot to do with how we got them. For example, a cluster of acne scars, even just one or two ice-pick scars, on an otherwise smooth cheek won't be met with the same acceptance that a scar acquired in a childhood accident might be. My older brother once pushed me off the top bunk bed, sending me to the floor with a new gash over my eyebrow. The scar is now faded and barely noticeable, but when I see it in the mirror, memories of childhood flash briefly in my mind. A scar is the technical term for tissue the body makes to right a wrong. In the process an amazing num ber of events happen as though preprogrammed. A cut from a broken wineglass (don't retrieve them from the fireplace!), a scrape from the pavement, an incision from © Copyright 2000, David J. Leffell. MD. All rights reserved. 190 The Bas i c s "WILL I HAVE A SCAR?" This is the most common question I hear when I talk about cosmetic procedures and reconstructive surgery. It is a smart question, but it took me a while to really understand what my patients meant by asking it. -

Scars and What to Do About Them

#33: SCARS PATIENT Scars and what to do PERSPECTIVES about them A scar forms as a normal part of the skin’s healing KELOIDS process. Scars may form from surgery, trauma Keloids are a special type of scar that (accidents, burns, etc.), infections such as chicken- become larger than the original wound. These can form even after a minor injury. pox, or inflammation in the skin such as acne. Predicting when and if a keloid will form is not possible, but they may be more likely to form in certain anatomic TYPES OF SCARS locations such as the earlobes. Scars may be flat, indented, or raised. Scars may be lighter or darker Keloids can be difficult to treat. The goal in color, pink or red. Hypertrophic scars and keloid scars form when of treatment is to improve the symptoms an excessive amount of scar tissue is formed, making the scar more and appearance. The following treatment raised than usual. A hypertrophic scar is an exaggerated type of options are available for this type of scar: scar but stays within the edges of the injury. A keloid scar spills over beyond the edges of the injury and may grow much like a tumor. » Injection of corticosteroids or other medications into the keloid The type of scar depends on many factors including age, location on » Silicone sheets and gels body, and skin type. In time, most scars become less noticeable, but » Compression earrings, garments, scars do not go away completely. or devices » Cryotherapy WHEN TO SEEK TREATMENT FOR A SCAR » Laser In most people, scars do not cause significant problems. -

Seborrheic Keratoses Brochure

If you have questions about your skin Seborrheic health, call 238-2501 or 1-800-332-7156 to schedule an appointment with one of Keratoses our board certified dermatologists. Seborrheic Seborrheic keratoses (SKs) are For more information visit www.billingsclinic.com/dermatology very common non-cancerous Keratoses skin growths which are found almost anywhere on the body. People usually have more than one. SKs often start as small raised areas or dry patches. They typically thicken and can develop a rough texture. Some appear warty, others smooth and waxy. Their size is quite variable ranging from smaller than a dime to larger than a half-dollar. Many SKs are brown, but can range in color from light yellow to black. Most have a stuck-on appearance. Although it appears as if you can scratch them off, they often recur. Billings Clinic Dermatology Center 801 North 29th Street Billings, Montana 59101 406-238-2500 or 1-800-332-7156 www.billingsclinic.com/dermatology 0611 JG Dermatology Causes Cryotherapy Seborrheic Keratoses Although the cause of SKs is unknown, they Nitrogen, in its liquid form, is extremely cold tend to run in families. This is particularly and is typically applied to the skin with a true for individuals who have many SKs or spray gun. Cotton-tipped applicators can who get them at younger ages. Sun also be used. This treatment is similar to exposure may be a contributing factor in frostbite and causes the SK to fall off in a few some people; however these growths often days. A blister may form under the skin develop in areas covered from the sun.