CASD Cemiss Quarterly Autumn 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Year in Review 2008

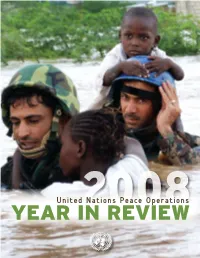

United Nations Peace Operations YEAR IN2008 REVIEW asdf TABLE OF CONTENTS 12 ] UNMIS helps keep North-South Sudan peace on track 13 ] MINURCAT trains police in Chad, prepares to expand 15 ] After gaining ground in Liberia, UN blue helmets start to downsize 16 ] Progress in Côte d’Ivoire 18 ] UN Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea is withdrawn 19 ] UNMIN assists Nepal in transition to peace and democracy 20 ] Amid increasing insecurity, humanitarian and political work continues in Somalia 21 ] After nearly a decade in Kosovo, UNMIK reconfigures 23 ] Afghanistan – Room for hope despite challenges 27 ] New SRSG pursues robust UN mandate in electoral assistance, reconstruction and political dialogue in Iraq 29 ] UNIFIL provides a window of opportunity for peace in southern Lebanon 30 ] A watershed year for Timor-Leste 33 ] UN continues political and peacekeeping efforts in the Middle East 35 ] Renewed hope for a solution in Cyprus 37 ] UNOMIG carries out mandate in complex environment 38 ] DFS: Supporting peace operations Children of Tongo, Massi, North Kivu, DRC. 28 March 2008. UN Photo by Marie Frechon. Children of Tongo, 40 ] Demand grows for UN Police 41 ] National staff make huge contributions to UN peace 1 ] 2008: United Nations peacekeeping operations observes 60 years of operations 44 ] Ahtisaari brings pride to UN peace efforts with 2008 Nobel Prize 6 ] As peace in Congo remains elusive, 45 ] Security Council addresses sexual violence as Security Council strengthens threat to international peace and security MONUC’s hand [ Peace operations facts and figures ] 9 ] Challenges confront new peace- 47 ] Peacekeeping contributors keeping mission in Darfur 48 ] United Nations peacekeeping operations 25 ] Peacekeepers lead response to 50 ] United Nations political and peacebuilding missions disasters in Haiti 52 ] Top 10 troop contributors Cover photo: Jordanian peacekeepers rescue children 52 ] Surge in uniformed UN peacekeeping personnel from a flooded orphanage north of Port-au-Prince from1991-2008 after the passing of Hurricane Ike. -

Security & Defence European

a 7.90 D 14974 E D European & Security ES & Defence 6/2019 International Security and Defence Journal COUNTRY FOCUS: AUSTRIA ISSN 1617-7983 • Heavy Lift Helicopters • Russian Nuclear Strategy • UAS for Reconnaissance and • NATO Military Engineering CoE Surveillance www.euro-sd.com • Airborne Early Warning • • Royal Norwegian Navy • Brazilian Army • UAS Detection • Cockpit Technology • Swiss “Air2030” Programme Developments • CBRN Decontamination June 2019 • CASEVAC/MEDEVAC Aircraft • Serbian Defence Exports Politics · Armed Forces · Procurement · Technology ANYTHING. In operations, the Eurofighter Typhoon is the proven choice of Air Forces. Unparalleled reliability and a continuous capability evolution across all domains mean that the Eurofighter Typhoon will play a vital role for decades to come. Air dominance. We make it fly. airbus.com Editorial Europe Needs More Pragmatism The elections to the European Parliament in May were beset with more paradoxes than they have ever been. The strongest party which will take its seats in the plenary chambers in Brus- sels (and, as an expensive anachronism, also in Strasbourg), albeit only for a brief period, is the Brexit Party, with 29 seats, whose programme is implicit in their name. Although EU institutions across the entire continent are challenged in terms of their public acceptance, in many countries the election has been fought with a very great deal of emotion, as if the day of reckoning is dawning, on which decisions will be All or Nothing. Some have raised concerns about the prosperous “European Project”, which they see as in dire need of rescue from malevolent sceptics. Others have painted an image of the decline of the West, which would inevitably come about if Brussels were to be allowed to continue on its present course. -

Democratic Republic of the Congo Page 1 of 37

2008 Human Rights Report: Democratic Republic of the Congo Page 1 of 37 2008 Human Rights Report: Democratic Republic of the Congo BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR 2008 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices February 25, 2009 The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is a nominally centralized republic with a population of approximately 60 million. The president and the lower house of parliament (National Assembly) are popularly elected; the members of the upper house (the Senate) are chosen by provincial assemblies. Multiparty presidential and National Assembly elections in 2006 were judged to be credible, despite some irregularities, while indirect elections for senators in 2007 were marred by allegations of vote buying. Internal conflict in the eastern provinces of North and South Kivu, driven to a large degree by the illegal exploitation of natural resources, as well as a separate conflict in the western province of Bas-Congo, had an extremely negative effect on security and human rights during the year. The Goma peace accords signed in January by the government and more than 20 armed groups from the eastern provinces of North and South Kivu provided for a cease-fire and charted a path toward sustainable peace in the region. Progress was uneven, with relative peace in South Kivu and the continued participation of the South Kivu militias in the disengagement process. In North Kivu, what little progress was made in implementing the accords during the first half of the year unraveled with the renewed fighting that began in August, perpetuating lawlessness in many areas of the east. -

1 Statement by Mr Alain Le Roy, Under-Secretary-General For

Statement by Mr Alain Le Roy, Under-Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations General Assembly Thematic debate: "UN Peacekeeping - looking into the future" 22 June 2010 Mr President, distinguished members of the General Assembly, I wish to thank the President of the General Assembly for arranging this interactive debate on peacekeeping providing an opportunity to exchange views on the future of United Nations peacekeeping. It is an extremely valuable and timely debate marking the 10th anniversary of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations led by Mr Brahimi. Since the panel published its landmark report ten years ago UN peacekeeping has undergone remarkable changes. In 2000 the level of deployment was 20,000. Today, UN peacekeeping deploys over 124,000 peacekeepers in 16 missions around the world, making it one of the most dynamic and challenging collective endeavours to promote international peace and security. Without the so-called Brahimi report we would not have been able to sustain this unprecedented surge. Building on the report’s recommendations and Member States’ support the peacekeeping machinery was strengthened, both in the field and at headquarters. The Report was extremely farsighted and many of the issues which it identified remain with us today. Fundamentally it reminded us that UN peacekeeping depended upon a partnership between the Security Council, the General Assembly, the Secretariat, Troop and Police contributors and the host governments. It laid the foundation for policy consensus among peacekeeping stakeholders regarding the use and application of UN peacekeeping. It underlined that peacekeeping missions should deploy only when there is a peace to keep. -

Central Asia-Caucasus

Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst BI-WEEKLY BRIEFING VOL. 11 NO. 9 6 May 2009 Searchable Archives with over 1,500 articles at http://www.cacianalyst.org ANALYTICAL ARTICLES: FIELD REPORTS: IS THE WEST LOSING THE ENERGY GAME IN THE CASPIAN? BORDER DELIMITATION PROBLEMS BE- Alman Mir Ismail TWEEN TAJIKISTAN AND UZBEKISTAN Erkin Akhmadov RUSSIA AND NATO MANEUVER NEW PLAN FOR AFGHANISTAN – THE ROLE OVER GEORGIA OF UZBEKISTAN AND ITS IMPLICATIONS Richard Weitz Umida Hashimova KYRGYZ REGIME USES ANTI-KURDISH AUDIT LEADS TO SCANDAL FOR TAJIK NA- PROTESTS FOR POLITICAL ENDS TIONAL BANK Erica Marat Suhrob Majidov EXPROPRIATION OF PROPERTY GENERATES TURKISH-ARMENIAN BREAKTHROUGH FRUSTRATION IN TAJIKISTAN MAY BE FAR AWAY Rustam Turaev Haroutiun Khachatrian NEWS DIGEST Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst BI-WEEKLY BRIEFING VOL. 11 NO. 9 6 MAY 2009 Contents Analytical Articles IS THE WEST LOSING THE ENERGY GAME IN THE CASPIAN? 3 Alman Mir Ismail RUSSIA AND NATO MANEUVER OVER GEORGIA 6 Richard Weitz KYRGYZ REGIME USES ANTI-KURDISH PROTESTS FOR POLITICAL ENDS 9 Erica Marat TURKISH-ARMENIAN BREAKTHROUGH MAY BE FAR AWAY 12 Haroutiun Khachatrian Field Reports BORDER DELIMITATION PROBLEMS BETWEEN TAJIKISTAN AND UZBEKISTAN 15 Erkin Akhmadov NEW PLAN FOR AFGHANISTAN – THE ROLE OF UZBEKISTAN 16 AND ITS IMPLICATIONS Umida Hashimova AUDIT LEADS TO SCANDAL FOR TAJIK NATIONAL BANK 18 Suhrob Majidov EXPROPRIATION OF PROPERTY GENERATES FRUSTRATION IN TAJIKISTAN 19 Rustam Turaev News Digest 21 THE CENTRAL ASIA-CAUCASUS ANALYST Editor: Svante E. Cornell Associate Editor: Niklas Nilsson Assistant Editor, News Digest: Alima Bissenova Chairman, Editorial Board: S. Frederick Starr The Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst is an English-language journal devoted to analysis of the current issues facing Central Asia and the Caucasus. -

Protecting Civilians in the Context of UN Peacekeeping Operations

About this publication Since 1999, an increasing number of United Nations peacekeeping missions have been expressly mandated to protect civilians. However, they continue to struggle to turn that ambition into reality on the ground. This independent study examines the drafting, interpretation, and implementation of such mandates over the last 10 years and takes stock of the successes and setbacks faced in this endeavor. It contains insights and recommendations for the entire range of United Nations protection actors, including the Security Council, troop and police contributing countries, the Secretariat, and the peacekeeping operations implementing protection of civilians mandates. Protecting Civilians in the Context Protecting Civilians in the Context the Context in Civilians Protecting This independent study was jointly commissioned by the Department of Peace keeping Opera- Operations Peacekeeping UN of tions and the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs of the United Nations. of UN Peacekeeping Operations Front cover images (left to right): Spine images (top to bottom): The UN Security Council considers the issue of the pro A member of the Indian battalion of MONUC on patrol, 2008. Successes, Setbacks and Remaining Challenges tection of civilians in armed conflict, 2009. © UN Photo/Marie Frechon. © UN Photo/Devra Berkowitz). Members of the Argentine battalion of the United Nations Two Indonesian members of the African Union–United Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) assist an elderly Nations Hybrid operation in Darfur (UNAMID) patrol as woman, 2008. © UN Photo/Logan Abassi. women queue to receive medical treatment, 2009. © UN Photo/Olivier Chassot. Back cover images (left to right): Language: ENGLISH A woman and a child in Haiti receive emergency rations Sales #: E.10.III.M.1 from the UN World Food Programme, 2008. -

Security Council Open Debate on Women, Peace and Security – 29 October 2008 Extract Meeting Transcript / English S/PV.6005

Security Council Open Debate on Women, Peace and Security – 29 October 2008 Extract Meeting Transcript / English S/PV.6005 SOUTH AFRICA Mr. Kumalo (South Africa): May I begin by thanking Ms. Rachel Mayanja, Special Adviser to the Secretary-General on Gender Issues and Advancement of Women, Mr. Alain Le Roy, Under- Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations, Ms. Inés Alberdi, of the United Nations Development Fund for Women, and Ms. Sarah Taylor, of the NGO Working Group on Women, Peace and Security. Their contributions to this meeting have been invaluable. I have the honour to address the Security Council today on behalf of the member States of the Southern African Development Community (SADC), namely, Angola, Botswana, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Swaziland, the United Republic of Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Zambia and my own country, South Africa. SADC takes this opportunity to thank the Secretary-General for his report contained in document S/2008/622, which provides an assessment of measures taken to enhance the implementation of resolution 1325 (2000) on women, peace and security. We also take note of the assessment on the progress made in the protection of women against sexual and gender-based violence. The report also refers to resolution 1820 (2008) on sexual violence in conflict situations, which was unanimously adopted by the Council not long ago. While women may be the first casualties of war, they remain active agents of change and play a meaningful role in the recovery and reintegration of their families. Women are also instrumental in bringing about democracy and reconciliation in post-conflict societies. -

India Recent Split Among Various Hindu Extremist Parties Leads One to Think About Future of Extremism in Indian Politics

Report # 95 & 96 BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD East Asia, Central Asia, GCC, FC, China & Turkey Nadia Tasleem Weekly Report from 21 November 2009 to 4 December 2009 Presentation: 10 December 2009 This report is based on the review of news items focusing on political, economic, social and geo-strategic developments in various regions namely; East Asia, Central Asia, GCC, FC, China and Turkey from 21 November 2009 to 20 December 2009 as have been collected by interns. Prelude to Summary: This report tries to highlight major issues being confronted by various Asian states at political, geo-strategic, social and economic front. On one hand this information helps one to build deep understanding of these regions. It gives a clear picture of ongoing pattern of developments in various states hence leads one to find similarities and differences amid diverse issues. On the other hand thorough and deep analysis compels reader to raise a range of questions hence provides one with an opportunity to explore more. Few such questions that have already been pointed out would be discussed below. To begin with India recent split among various Hindu extremist parties leads one to think about future of extremism in Indian politics. Recently released Liberhan Commission Report has convicted BJP and other extremists for their involvement in demolition of Babri Mosque 17 years ago. In response to this report BJP has out rightly denied their involvement rather has condemned government for her efforts to shatter BJP’s image. An undeniable fact however remains that L.K. Advani; one of the key members of BJP had been an active participant in Ayodhya movement. -

Russia's Kosovo: a Critical Geopolitics of the August 2008 War Over South

Toal.fm Page 670 Monday, December 22, 2008 10:20 AM Russia’s Kosovo: A Critical Geopolitics of the August 2008 War over South Ossetia Gearóid Ó Tuathail (Gerard Toal)1 Abstract: A noted political geographer presents an analysis of the August 2008 South Ossetian war. He analyzes the conflict from a critical geopolitical perspective sensitive to the importance of localized context and agency in world affairs and to the limitations of state- centric logics in capturing the connectivities, flows, and attachments that transcend state bor- ders and characterize specific locations. The paper traces the historical antecedents to the August 2008 conflict and identifies major factors that led to it, including legacies of past vio- lence, the Georgian president’s aggressive style of leadership, and renewed Russian “great power” aspirations under Putin. The Kosovo case created normative precedents available for opportunistic localization. The author then focuses on the events of August 2008 and the competing storylines promoted by the Georgian and Russian governments. Journal of Eco- nomic Literature, Classification Numbers: H10, I31, O18, P30. 7 figures, 2 tables, 137 refer- ences. Key words: South Ossetia, Georgia, Russia, North Ossetia, Abkhazia, genocide, ethnic cleansing, Kosovo, Tskhinvali, Saakashvili, Putin, Medvedev, Vladikavkaz, oil and gas pipe- lines, refugees, internally displaced persons, Kosovo precedent. he brief war between Georgian government forces and those of the Russian Federation Tin the second week of August 2008 was the largest outbreak of fighting in Europe since the Kosovo war in 1999. Hundreds died in the shelling and fighting, which left close to 200,000 people displaced from their homes (UNHCR, 2008b). -

Security Council Distr.: General 4 June 2010 English Original: French

United Nations S/2010/286 Security Council Distr.: General 4 June 2010 English Original: French Letter dated 1 June 2010 from the Permanent Representative of France to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council I have the honour to transmit herewith a report on the work of the Security Council during the presidency of France in February 2010 (see annex). The document was prepared under my responsibility, following consultation with the other members of the Security Council. I should be grateful if you would have the present letter and its annex circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Gérard Araud 10-39015 (E) 090610 140610 *1039015* S/2010/286 Annex to the letter dated 1 June 2010 from the Permanent Representative of France to the United Nations addressed to the President of the Security Council Assessment of the work of the Security Council during the presidency of France (February 2010) Introduction Under the presidency of the Permanent Representative of France, Ambassador Gérard Araud, in February 2010, the Security Council engaged in an extensive programme of work. During the month, the Security Council held 8 closed consultations of the whole and 12 meetings. The Council adopted one resolution and produced four presidential statements. Africa The situation in Chad, the Central African Republic and the subregion On 17 February, the Council held consultations of the whole on the United Nations Mission in the Central African Republic and Chad (MINURCAT) during which members of the Council discussed the decision of Chad requesting the withdrawal of the Mission. -

For a Renewed Consensus on UN Peacekeeping Operations

Conference Series 1523 For a Renewed Consensus on UN Peacekeeping Operations Edited by Thierry Tardy GCSP Geneva Papers — Conference Series n°23 1 The opinions and views expressed in this document do not necessarily reflect the position of the Swiss authorities or the Geneva Centre for Security Policy. Copyright © Geneva Centre for Security Policy, 2011 2 GCSP Geneva Papers — Conference Series n°23 For a Renewed Consensus on UN Peacekeeping Operations Edited by Thierry Tardy This workshop and publication have been made possible thanks to the financial support of the Delegation for Strategic Affairs of the French Ministry of Defence GCSP Geneva Papers — Conference Series n°23, October 2011 The Geneva Centre for Security Policy The Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP) is an international training centre for security policy based in Geneva. An international foundation with over 40 member states, it offers courses for civil servants, diplomats and military officers from all over the world. Through research, workshops and conferences it pro- vides an internationally recognized forum for dialogue on timely issues relating to security and peace. The Geneva Papers and l’Esprit de Genève With its vocation for peace, Geneva is the city where international organizations, NGOs, and the academic community, working together, have the possibility of creating the essential conditions for debate and concrete action. The Geneva Pa- pers intend to serve the same goal by promoting a platform for constructive and substantive dialogue. Geneva Papers – Conference Series The Geneva Papers – Conference Series was launched in 2008 with the purpose of reflecting on the main issues and debates of events organized by the GCSP. -

Political Forum: 10 Questions on Georgia's Political Development

1 The Caucasus Institute for Peace, Democracy and Development Political Forum: 10 Questions on Georgia’s Political Development Tbilisi 2007 2 General editing Ghia Nodia English translation Kakhaber Dvalidze Language editing John Horan © CIPDD, November 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or oth- erwise, without the prior permission in writing from the proprietor. CIPDD welcomes the utilization and dissemination of the material included in this publication. This book was published with the financial support of the regional Think Tank Fund, part of Open Society Institute Budapest. The opinions it con- tains are solely those of the author(s) and do not reflect the position of the OSI. ISBN 978-99928-37-08-5 1 M. Aleksidze St., Tbilisi 0193 Georgia Tel: 334081; Fax: 334163 www.cipdd.org 3 Contents Foreword ................................................................................................ 5 Archil Abashidze .................................................................................. 8 David Aprasidze .................................................................................21 David Darchiashvili............................................................................ 33 Levan Gigineishvili ............................................................................ 50 Kakha Katsitadze ...............................................................................67