Interview with Mr. Ronald Sikorski UNCLASSIFIED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tm 9-3305 Technical Manual Principles of Artillery Weapons Headquarters

Downloaded from http://www.everyspec.com TM 9-3305 TECHNICAL MANUAL PRINCIPLES OF ARTILLERY WEAPONS HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY 4 MAY 1981 Downloaded from http://www.everyspec.com *TM 9-3305 Technical Manual HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY No. 9-3305 Washington, DC, 4 May 1981 PRINCIPLES OF ARTILLERY WEAPONS REPORTING ERRORS AND RECOMMENDING IMPROVEMENTS You can help improve this manual. If you find any mistakes or if you know of a way to improve the procedures, please let us know. Mail your letter, DA Form 2028 (Recommended Changes to Publications and Blank Forms), or DA Form 2028-2, located in the back of this manual, direct to: Commander, US Army Armament Materiel Readiness Command, ATTN: DRSAR-MAS, Rock Island, IL 61299. A reply will be furnished to you. Para Page PART ONE. GENERAL CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1-1 1-1 2. HISTORY OF DEVELOPMENT Section I. General ....................................................................................................................... 2-1 2-1 II. Development of United States Cannon Artillery......................................................... 2-8 2-5 III. Development of Rockets and Guided Missiles ......................................................... 2-11 2-21 CHAPTER 3. CLASSIFICATION OF CURRENT FIELD ARTILLERY WEAPONS Section I. General ....................................................................................................................... 3-1 3-1 -

Army Tm 9-1025-211-10 Marine Corps Tm 08198A-10/1 Supersedes Copy Dated 1 Oct 1979

ARMY TM 9-1025-211-10 MARINE CORPS TM 08198A-10/1 SUPERSEDES COPY DATED 1 OCT 1979 TECHNICAL MANUAL PMCS PAGE 2-10 OPERATOR'S MANUAL OPERATION UNDER PAGE USUAL CONDITIONS 2-49 FOR MISFIRE AND CHECK PAGE HOWITZER, MEDIUM, TOWED: FIRING PROCEDURES 2-115 155-MM, M198 TROUBLESHOOTING PAGE (1025-01-026-6648) (EIC:3EL) PROCEDURES 3-1 MAINTENANCE PAGE PROCEDURES 3-15 PREPARATION PAGE FOR FIRING 4-32 LUBRICATION INSTRUCTIONS APPX F DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution is unlimited. HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY HEADQUARTERS, U.S. MARINE CORPS JANUARY 1991 Technical Manuals ARMY TM 9-1025-211-10* No. 9-1025-211-10* MARINE CORPS TM 08198A-10/1 No. 08198A-10/1* HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY, U.S. MARINE CORPS, Washington DC, 14 January 1991 OPERATOR'S MANUAL FOR HOWITZER, MEDIUM, TOWED: 155-MM, M198 (EIC: 3EL) (1025-01-026-6648) REPORTING ERRORS AND RECOMMENDING IMPROVEMENTS You can help improve this publication. If you find any mistakes or if you know of a way to improve the procedures, please let us know. Submit your DA Form 2028 (Recommended Changes to Publications and Blank Forms), through the Internet, on the Army Electronic Product Support (AEPS) website. The Internet address is http://aeps.ria.army.mil. If you need a password, scroll down and click on "ACCESS REQUEST FORM". The DA Form 2028 is located in the ONLINE FORMS PROCESSING section of the AEPS. Fill out the form and click on SUBMIT. Using the form on the AEPS will enable us to respond quicker to your comments and better manage the DA Form 2028 program. -

NSIAD-96-59 Army and Marine Corps M198 Howitzer B-262208

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Chairman, Committee on GAO National Security, House of Representatives December 1995 ARMY AND MARINE CORPS M198 HOWITZER Maintenance Problems Are Not Severe Enough to Accelerate Replacement System GAO/NSIAD-96-59 United States General Accounting Office GAO Washington, D.C. 20548 National Security and International Affairs Division B-262208 December 27, 1995 The Honorable Floyd Spence Chairman, Committee on National Security House of Representatives Dear Mr. Chairman: As you requested, we obtained information on the Marine Corps’ and Army’s reported maintenance problems with the M198 155-millimeter (mm) towed howitzer to determine whether these reported problems justify accelerating the development of a replacement weapon. We also obtained information regarding the Marine Corps’ and the Army’s planned development of a new, light-weight 155-mm howitzer. Active and reserve Marine Corps artillery units use the M198 howitzer for Background all direct support, general support, and reinforcing artillery missions. Army light cavalry units use the M198 for direct support, whereas airborne and airmobile infantry units use the M198 only for general support and reinforcing missions. The M198 howitzers, first delivered to the services in 1979, are approaching the end of their 20-year service life. Marine Corps and Army users of the M198 want to replace the 15,600-pound howitzer with a lighter-weight weapon to ease the operational burden on crews and to improve air and ground mobility. The Marines have found it difficult to tow the M198 over soft terrain, and only their heavy-lift helicopter can move the weapon by air. -

Howitzers and Seven New Regiments: Indian Army’S Game Changer in Mountainous Terrain

P K CHAKRAVORTY Howitzers and Seven New Regiments: Indian Army’s Game Changer in Mountainous Terrain P K Chakravorty The words of former United States Secretary of State Hillary Clinton at the India Today Conclave held at Mumbai on March 10, 2018 were, indeed, music for the Indian ears. She referred to India as a country which is accepted as a power that counts by both political parties across the United States.1 This has been possible due to the robustness of the Indian economy and its armed forces. ‘Make in India’ has been a flagship project of the current government and the Regiment of Artillery has left no stone unturned to modernise, with emphasis on ‘Make in India’. Modernisation of the Indian Amy is being undertaken to meet the two-front threats from China and Pakistan. For this, the focus is on Network-Centric Warfare (NCW). Like other combat arms, the Indian Artillery is currently in an NCW environment and has to provide surveillance and reconnaissance, resulting in target acquisition which would lead to engagement which needs to be monitored to undertake post strike damage assessment and ensure that the target has been destroyed. In NCW, the artillery shapes the battlefield, degrades the enemy’s war- Major General PK Chakravorty (Retd) is Senior Fellow (Veteran) Centre for Land Warfare Studies, New Delhi. 104 CLAWS Journal l Summer 2018 HOWITZERS AND SEVEN NEW REGIMENTS waging capability, destroys his field defences, communication sites, and logistics echelons, thereby paralysing him and, thus, accomplishing own mission. Along with the ‘Make in India’ projects, the artillery has been at the forefront of modernising its inventory with state-of-the-art equipment. -

The Rojava Revolution

The Rojava Revolution By Aram Shabanian Over five years ago an uprising in Dara’a, Southern Syria, set into motion the events that would eventually culminate in the multifront Syrian Civil War we see today. Throughout the conflict one group in particular has stuck to its principles of selfdefense, gender equality, democratic leadership and environmental protectionism. This group, the Kurds of Northern Syria (Henceforth Rojava), have taken advantage of the chaos in their country to push for more autonomy and, just perhaps, an independent state. The purpose of this paper is to convince the reader that increased support of the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) would be beneficial to regional and international goals and thus should be initiated immediately. Throughout this paper there will be sources linking to YouTube videos; use this to “watch” the Rojava Revolution from beginning to end for yourself. In the midst of the horror that is the Syrian Civil War there is a single shining glimmer of hope; Rojava, currently engaged in a war for survival and independence whilst simultaneously engaging in a political experiment the likes of which has never been seen before. The Kurds are the secondlargest ethnic group in the middle east today, spanning four countries (Iraq, Iran, Syria and Turkey) but lacking a home state of their own. Sometimes called the ultimate losers in the SykesPicot agreement, the Kurds have fought for a homeland of their own ever since said agreement was signed in 1916. The Kurds in all of the aforementioned nations are engaged in some degree of insurrection or another. -

Lightweight 155Mm Howitzer

Lightweight 155mm Howitzer (LW 155) Lightweight 155mm Howitzer (LW 155) (LW 155mm Howitzer Lightweight DESCRIPTION AND SPECIFICATIONS PROGRAM STATUS The M777 Lightweight 155mm Howitzer (M777) • Current Low-rate initial production for 94 Marine incorporates innovative designs to achieve lighter Corps guns with conventional fire control weight without sacrificing the range, stability, • Developmental testing of howitzers equipped with accuracy, or durability of the current M198 howitzer digital fire control successful and near completion system it replaces. The lighter weight is achieved • Digital fire control program has synchronized the through lower trunnion height and the use of high- with the basic howitzer strength titanium, a primary component of the • 1QFY05 Operational testing commenced lower carriage and cradle assembly. Two M777s can • Once type classified, the digital fire control- be transported in a C130 aircraft and can also be equipped howitzer will be designated the dropped by parachute. The M777’s lighter weight, M777A1. All future howitzers will be procured in smaller footprint, and lower profile provide improved the M777A1 configuration. strategic deployability, tactical mobility, and survivability. The primer feeding mechanism, loader- PROJECTED ACTIVITIES Provides direct, reinforcing, and assist, digital fire control, and other automation • 2QFY05 Joint Milestone C for full-rate production enhancements will improve survivability, lethality, decision of the M777A1 general support fire to maneuver and combat reliability, as well as provide light • 2QFY05 Full-rate production contract award and artillery with a semi-autonomous capability that is production begins forces and directs support artillery currently found only in self-propelled howitzers. • 4QFY06 Army initial operational capability of CONTRACTORS for Stryker Brigade Combat Teams. -

Backpack Helicopter

Backpack helicopter Artist's depiction of a helibackpack with counter-rotating twin rotors A backpack helicopter or helibackpack is a helicopter motor and rotor and controls assembly that can be strapped to a man's back, so that he wan walk about on the ground wearing it, and can use it to fly. Its harness, like a parachute harness should have a strap between the legs, so that the pilot does not fall out of the harness during flight. Related are devices like a backpack helicopter which also include a seat and leg supports and are actually very small open-topped ordinary helicopters. (See also jetpack.) Several inventors have tried to make backpack helicopters, with mixed results. In theory, a helicopter would be more efficient than a rocket pack or jetpack, possessing a greater specific impulse, and being more suited to hovering due to the smaller velocities of the propelled gases. Examples which are pure backpack:- http://english.pravda.ru/main/2002/06/11/30172.html describes a Russian backpack helicopter. The Heliofly was a make which was designed in Germany in 1941 onwards. See [1] and [2]. Or search for Heliofly in http://www.altavista.com . Pentecost HX-1 Hoppi-Copter Rhyme (made in Japan) Examples which have a seat:- SoloTrek XFV (Exo-skeletor Flying Vehicle). See http://www.vortechonline.com for various models which have seats. They formerly also made a pure backpack model with two very long rotor blades driven by a little propane- powered jet motor at the end of each blade. GenH4 1 Backpack helicopters occur sometimes in fiction. -

Tm 55-1025-211-14

TM 55-1025-211-14 Technical Manual Transportability Guidance Transporting the Howitzer, Medium, Towed, 155-MM, M198 (NSN 1025-01-026-6648) By Air, Highway, Water and Rail Headquarters, Department of the Army September 1979 WARNING RADIOACTIVE MATERIALS Items containing radioactive tritium gas are identified by a radioactive warning label. These items are designed so as to preclude a health hazard; however, in the event that they are not illuminated, or there is evidence of breakage, the local radiation protection officer (RPO) must be notified. If a radioactive source is broken, open doors or windows (if inside) and evacuate the room or area for one-half hour. If it is suspected that skin contact has been made with any contaminated area, immediately clean the skin with lukewarm water and nonabrasive soap. TM 55-1025-211-14 C2 Change) HEADQUARTERS ) DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY No. 2 ) Washington, DC, 1 September 1987 TRANSPORTABILITY GUIDANCE TRANSPORTING THE HOWITZER, MEDIUM TOWED, 155-MM, M198 BY AIR, HIGHWAY, WATER AND RAIL This change updates the Dimensions, Weight, and Volume Table on page 2-1 and adds procedures for using the M198 Air Transportability Kit to Chapter 3. TM 55-1025-211-14, 1 September 1979, is changed as follows: 1. New or changed material is indicated by a vertical bar in the margin. 2. Remove old pages and insert new pages as indicated below: Remove pages Insert pages 1-1, 1-2 1-1, 1-2 2-1, 2-2 2-1, 2-2 3-5 3-5, 3-6 A-1, A-2 A-1, A-2 3. -

LIGHTWEIGHT 155Mm (LW155)

LIGHTWEIGHT 155mm (LW155) SYSTEM PERFORMANCE SPECIFICATION 1.0 SCOPE 1.1 Identification (TBD) 1.2 System Overview The LW 155 will replace all US Marine Corps (USMC) cannon systems and be used as a direct support weapon. The US Army (Army) will use the system as a general support weapon in the light forces and as a direct support weapon for the Light Cavalry Regiment replacing all of the M198 155mm towed howitzers. 1.3 Document Overview This system specification describes the configuration of the Lightweight 155 (LW 155) formerly known as the Advanced Towed Cannon System (ATCAS). This specification is used to describe the performance requirements of the LW 155 and contains the operational and interface criteria for the system. Both services require the system to have the capability to accept the Pre-planned Product Improvements (P3I) listed in appendix A of this specification. The Army requires that a number of the P3I be on their production system; while, the USMC may procure them, as a separate action, to be added to their production system. 1.4 Security Classification (TBD) 2.0 APPLICABLE DOCUMENTS The following documents form a part of this specification to the extent specified herein. In the event of conflict between the documents referenced herein and the content of this specification, the content of this specification shall be considered a superseding requirement. 2.1 Government 2.1.1 Specifications and Standards 2.1.1.1 Mandatory 1 QPL-46168-27 Coating, Aliphatic Polyurethane, Chemical Agent Resistant MIL-STD-209(H) Slinging and -

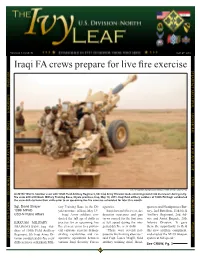

Iraqi FA Crews Prepare for Live Fire Exercise Steadfast and Loyal Warrior Ironhorse Longknife Fit for Any Test Devil Devil Any Test Fit For

Volume 1, Issue 30 may 27, 2011 Iraqi FA crews prepare for live fire exercise Steadfast and Loyal and Steadfast Warrior Ironhorse LongKnife Fit for Any Test Devil Any Test Fit for Fit for Any Test Devil Any Test Fit for U.S. Army photo by Sgt. David Strayer, 109th MPAD, USD-N PAO An M198 155mm howitzer crew with 105th Field Artillery Regiment, 5th Iraqi Army Division loads a training round into the breach during a dry- LongKnife Ironhorse fire crew drill at Kirkush Military Training Base, Diyala province, Iraq, May 19, 2011. Iraqi field artillery soldiers of 105th FA Regt. conducted the crew drills to hone their skills prior to an upcoming live fire exercise scheduled for later this month. Sgt. David Strayer tary Training Base in the Di- agencies. quarters and Headquarters Bat- 109th MPAD yala province of Iraq, May 19. Iraqi forward observers, fire tery, 2nd Battalion, 11th Field USD-N Public Affairs Iraqi Army soldiers con- direction operators and gun Artillery Regiment, 2nd Ad- ducted the full speed drills to crews synced for the first time vise and Assist Brigade, 25th Warrior KIRKUSH MILITARY practice for an upcoming live at full speed during the inte- Infantry Division. “It gave TRAINING BASE, Iraq – Sol- fire exercise prior to a provin- grated dry fire crew drills. them the opportunity to field diers of 105th Field Artillery cial capstone exercise demon- “There were several pur- this new artillery equipment, Regiment, 5th Iraqi Army Di- strating capabilities and co- poses to this training exercise,” and employ the M198 weapon Steadfast and Loyal and Steadfast vision conducted dry-fire crew operative operations between said Capt. -

Rigging M198, 155-MM Howitzer

FM 4-20.127 (FM 10-527) TO 13C7-10-191 ` Airdrop of Supplies and Equipment: Rigging M198, 155-MM Howitzer JUNE 2004 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE This publication is available at Army Knowledge Online www.us.army.mil *FM 4-20.127 (FM 10-527) TO 13C7-10-191 FIELD MANUAL No. 4-20.127 ...................................................................................... DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY TECHNICAL ORDER DEPARTMENTDEPARTMENT OFDEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE No. 13C7-10-191 ..................................................................................Washington, DC, 29 June 2004 Airdrop of Supplies and Equipment: Rigging M198, 155-MM Howitzer Contents ................................................................................................................................ Page Preface ........................................................................................................................iii Introduction ................................................................................................................iv Description of Load ......................................................................................................iv Special Considerations ................................................................................................iv Chapter 1 Rigging M198, 155-mm Howitzer on a Type V Platform Description of Load ....................................................................................................1-1 -

News Call Change of Command for Operation New Dawn

News Call Change of Command for Operation New Dawn The September 1 name change from fantry Division, taught a week-long of human terrain teams (HTTs), spe- Operation Iraqi Freedom to Operation EOD refresher course for Iraqi police cially trained groups of American sol- New Dawn, coupled with the transfer officers in Ramadi. Later that month, diers and civilians with expertise in of command of U.S. Forces-Iraq from soldiers of 1st Advise and Assist cultural awareness who interview lo- GEN Raymond T. Odierno to GEN Brigade, 3rd Infantry, helped an ISF-led cal populations in Iraq and pass on in- Lloyd J. Austin III, signified a shift in humanitarian aid mission near Bagh- formation about their culture and way the mission of U.S. forces in Iraq. The dad. The Iraqi forces were in the lead as of life to commanders on the ground. mission now is to advise and assist medical care was administered and That information helps commanders Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) so that they food and school supplies were distrib- make more informed decisions that are prepared to take over when the uted, and they reconnected with the lo- reflect cultural awareness and sensi- U.S. military leaves by the end of cal population and gained credibility. tivity. As of early October, there were 2011. The Army is leading that mis- They also gained experience in plan- about 15 HTTs operating in Iraq. Sim- sion in many ways. ning and resourcing such missions. ulated towns and provinces at the In September, the 731st Explosive Another way U.S.