Further Thoughts on E18 Saltfleetby. Futhark 9–10

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lincolnshire. Louth

DIRECI'ORY. J LINCOLNSHIRE. LOUTH. 323 Mary, Donington-upon-Bain, Elkington North, Elkington Clerk to the Commissioners of Louth Navigation, Porter South, Farforth with Maidenwell, Fotherby, Fulstow, Gay Wilson, Westgate ton-le-Marsh, Gayton-le-"\\'old, Grains by, Grainthorpe, Clerk to Commissioners of Taxes for the Division of Louth Grimblethorpe, Little Grimsby, Grimoldby, Hainton, Hal Eske & Loughborough, Richard Whitton, 4 Upgate lin,o1on, Hagnaby with Hannah, Haugh, Haugham, Holton Clerk to King Edward VI. 's Grammar School, to Louth le-Clay, Keddington, Kelstern, Lamcroft, Legbourne, Hospital Foundation & to Phillipson's & Aklam's Charities, Louth, Louth Park, Ludborough, Ludford Magna, Lud Henry Frederic Valentine Falkner, 34 Eastgate ford Parva, Mablethorpe St. Mary, Mablethorpe St. Collector of Poor Rates, Charles Wilson, 27 .Aswell street Peter, Maltby-le-Marsh, Manby, Marshchapel, Muckton, Collector of Tolls for Louth Navigation, Henry Smith, Ormsby North, Oxcombe, Raithby-cum-:.Vlaltby, Reston Riverhead North, Reston South, Ruckland, Saleby with 'fhores Coroner for Louth District, Frederick Sharpley, Cannon thorpe, Saltfleetby all Saints, Saltfleetby St. Clement, street; deputy, Herbert Sharpley, I Cannon street Salttleetby St. Peter, Skidbrook & Saltfleet, Somercotes County Treasurer to Lindsey District, Wm.Garfit,Mercer row North, Somercotes South, Stenigot, Stewton, Strubby Examiner of Weights & Measures for Louth district of with Woodthorpe, Swaby, 'fathwell, 'fetney, 'fheddle County, .Alfred Rippin, Eastgate thorpe All Saints, Theddlethorpe St. Helen, Thoresby H. M. Inspector of Schools, J oseph Wilson, 59 Westgate ; North, Thoresby South, Tothill, Trusthorpe, Utterby assistant, Benjamin Johnson, Sydenham ter. Newmarket Waith, Walmsgate, Welton-le-Wold, Willingham South, Inland Revenue Officers, William John Gamble & Warwick Withcall, Withern, Worlaby, Wyham with Cadeby, Wyke James Rundle, 5 New street ham East & Yarborough. -

NOTICE of POLL Election of a County Councillor

NOTICE OF POLL East Lindsey Election of a County Councillor for Saltfleet & the Cotes Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a County Councillor for Saltfleet & the Cotes will be held on Thursday 6 May 2021, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of County Councillors to be elected is one. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Assentors ALDRIDGE Hawthorns, Main Road, Independent Freddie W Mossop (+) Steven J McMillan (++) Terry Covenham St Bartholomew, Louth, Lincolnshire, LN11 0PF LYONS 9 Carmen Crescent, Labour Party Lesley M A W Hough John D Hough (++) Chris Holton Le Clay, (+) Grimsby, Lincolnshire, DN36 5DD MCNALLY Toad Hall, Ark Road, The Conservative Party Alwyn N Drewery (+) Martin C Smith (++) Daniel North Somercotes, Candidate Louth, Lincolnshire, LN11 7NU 4. The situation of Polling Stations and the description of persons entitled to vote thereat are as follows: Station Ranges of electoral register numbers of Situation of Polling Station Number persons entitled to vote thereat Methodist Church Hall, High Street, Grainthorpe 64 AW-1 to AW-50 Methodist Church Hall, High Street, Grainthorpe 64 BK-1 to BK-555 Village Hall, Main Street, Gayton Le Marsh 65 BH-1 to BH-120 Church Institute, Main Road, Great Carlton 66 BL1-1 to BL1-124 Church Institute, -

East Lindsey Local Plan Alteration 1999 Chapter 1 - 1

Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE EAST LINDSEY LOCAL PLAN ALTERATION 1999 The Local Plan has the following main aims:- x to translate the broad policies of the Structure Plan into specific planning policies and proposals relevant to the East Lindsey District. It will show these on a Proposals Map with inset maps as necessary x to make policies against which all planning applications will be judged; x to direct and control the development and use of land; (to control development so that it is in the best interests of the public and the environment and also to highlight and promote the type of development which would benefit the District from a social, economic or environmental point of view. In particular, the Plan aims to emphasise the economic growth potential of the District); and x to bring local planning issues to the public's attention. East Lindsey Local Plan Alteration 1999 Chapter 1 - 1 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION Page The Aims of the Plan 3 How The Policies Have Been Formed 4 The Format of the Plan 5 The Monitoring, Review and Implementation of the Plan 5 East Lindsey Local Plan Alteration 1999 Chapter 1 - 2 INTRODUCTION TO THE EAST LINDSEY LOCAL PLAN 1.1. The East Lindsey Local Plan is the first statutory Local Plan to cover the whole of the District. It has updated, and takes over from all previous formal and informal Local Plans, Village Plans and Village Development Guidelines. It complements the Lincolnshire County Structure Plan but differs from it in quite a significant way. The Structure Plan deals with broad strategic issues and its generally-worded policies do not relate to particular sites. -

East Division. Binbrook, Saint Mary, Binbrook, Saint Gabriel. Croxby

2754 East Division. In the Hundred of Ludborough. I Skidbrooke cum Saltfleetj Brackenborough, ] Somercotes, North, Binbrook, Saint Mary, 1 Somercotes, South, Binbrook, Saint Gabriel. Covenham, Saint Bartholomew, ; ; Covenham, Saint Mary, Stewton, Croxby, 1 1 TathweU, Linwood, Fotherby, ', Grimsby Parva, Welton on the Wolds, Orford, jWithcall, Rasen, Middle, Ludborough, , Ormsby, North, Utterby, Wykeham, Rasen, Market, I Yarborough. Stainton le Vale, Wyham cum Cadeby. Tealby, In the Hundred of Calceworth. In t?ie Hundred of Wraggoe. Thoresway, I Aby with Greenfield, Thorganby, Benniworth, Biscathorpe, f Anderby, Walesby, Brough upon Bain cum Girsby, JAlford, Willingham, North. Hainton, Belleau, Ludford Magna, Ludford Parva, Beesby in the Marsh, In the Hundred of Wraggoe. "Willingham, South. Bilsby with Asserby, an$ Kirmond le Mire, Thurlby, Legsby with Bleasby and CoIIow, In the Hundred of Gartree. Claythorpe, Calceby, SixhiUs, ' ' •: .Asterby, Cawthorpe, Little, Torrington, East. Baumber, Belchford, Cumberworth, Cawkwell, Claxby, near Alford, Donington upon Bain, Farlsthorpe, In the Hundred of Bradley Gayton le Marsh, Haverstoe, West Division. Edlington, Goulceby, Haugh, Aylesby, Heningby, Horsington, Hannah cum Hagnaby, Barnoldby le Beck, Langton by Horncastle, Hogsthorpe, Huttoft, Beelsby, Martin, Legburn, Bradley, Ranby, Mablethorpe, Cabourn, Scamblesby, Mumby cum Chapel Elsey and Coats, Great, Stainton, Market, Langham-row, Coates, Little, Stennigot, Sturton, Maltby le Marsh, Cuxwold, Thornton. Markby, Grimsby, Great, Reston, South, Hatcliffe with Gonerby, In the Hundred of Louth Eske. Rigsby with Ailby, Healing, Alvingham, Sutton le Marsh, Irby, Authorpe, Swaby with White Pit, Laceby, Burwell, Saleby with Thoresthorpe, Rothwell, Carlton, Great, Carlton Castle, Strubby with Woodthorpe; Scartho, Theddlethorpe All Saints, Carlton, Little, Theddlethorpe Saint Helen, Swallow. Conisholme, Thoresby, South, East Division. Calcethorpe, Cockerington, North, or Saint Tothill, Trusthorpe, Ashby cum Fenby, Mary, . -

LINCOLNSHIRE. [KELLY's

790 FAR LINCOLNSHIRE. [KELLY's FARMERs-continued. Grant William1 Irby-in-the-Ma.rsb-, Burgh~ Greetham John, Stainfield, Wmgl:Jr Godfrey Edmund, Thealby hall, Burtorvon.- Grant Wm. N. Wildmore, Coningsby, Boston Greetham Joseph, Swinesheacr, Spalding Stather, Doncaster Grantham Arthnr1 Campaign .farm, -Bouth Greetham Richd. Fen, Heckington, Sleaford (iffidfrey Jarnes, Bricky~d rd. Tydd St. Ormsby, Alford Greetha.m Richard, Kirton fen, Boston Mary, Wisbech Grantbam Charles Fred, The Hall, Skegness Greetham Robert, Sutterton fen, Boston Godfrey John, West Butterwick, Doncaster Grantbatn Henry, Fulstow, Louth Greetham Mrs. Wm. Fen,Heckington,Sleaford Godfrey P. Lowgate, Tydd St. Mary, Wisbech Grantham John, Waddingham, Kirton Lind- Gresham Joseph, Washingborough, Lincoln Godfrey Mrs. R. Button St. James, Wisbech sey R.S.O Gresham Joshua, BrBnston, Lincoln Godfrey William, Fillingham, Lincoln Grantham Thomas, West Keal, Spilsby Gresswell Da.n Jennings, Swabyl Alford Godson Frank, Fen Blankney S.O Grnsham John, Yarborough, Louth Grice George, Westwood side, Bawtry Godson Frank, Temple Bruer, Grantham Grason Thomas, Chapel, .A.lford Griffin Aaron, Tt>tford, Horncastle Godson George, Fen, Heckington, Sleaford Grassam Mrs. Ca.rolint>, Spalding road, West Griffin Ephraim, Temple Brner, Grantham Godson John, Leake, Boston Pinchbeck, Spalding Griffin E. H. Heath, Metheringham, Lincoln Godson Joseph, Heckington, Sleaford Gratrix Thomas, Scredington, Falk:ingham Griffin George, Grange, Far Thorpe, West GOOson Richard, Heckington, Sleaford Gratton John, Washway,Whaplode, Spalding Ashby, Horncastle Godson Richard, Stow, Lincoln Gratton William, Button St. James, Wisbech Griffin Jas. Mill green, Pinchbeck, Spalding Goffl.n Alfred, Tattemhall Thorpe, Boston Gravt>ll Christopher, Epworth, Doncaster Griffin Moses, Asterby, Horncastle Golding Thos. Newland rd. Burfieet, Spa.lding Grn¥es Charles, Yawthorpe, G!Unsborough Grime Geo.A.Keal Coates ho. -

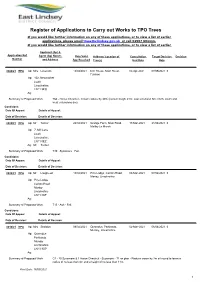

Register of Applications to Carry out Works to TPO Trees

Register of Applications to Carry out Works to TPO Trees If you would like further information on any of these applications, or to view a list of earlier applications, please email [email protected] or call 01507 601111. If you would like further information on any of these applications, or to view a list of earlier Applicant (Ap) & Application Ref Agent (Ag) Names Date Valid Address/ Location of Consultation Target Decision Decision Number and Address App Received Tree(s) End Date Date 0026/21 /TPA Ap: Mrs Laverack 12/03/2021 00:00:00Elm House, Main Street, 02-Apr-2021 07/05/2021 00:00:00 Fulstow Ap: 102, Newmarket Louth Lincolnshire LN11 9EQ Ag: Summary of Proposed Work T64 - Horse Chestnut - Crown reduce by 30% (current height 21m; east extension 5m; north, south and west extensions 6m). Conditions: Date Of Appeal: Details of Appeal: Date of Decision: Details of Decision: 0023/21 /TPA Ap: Mr Turner 24/02/2021 00:00:00Grange Farm, Main Road, 17-Mar-2021 21/04/2021 00:00:00 Maltby Le Marsh Ap: 7, Mill Lane Louth Lincolnshire LN11 0EZ Ag: Mr Turner Summary of Proposed Work T39 - Sycamore - Fell. Conditions: Date Of Appeal: Details of Appeal: Date of Decision: Details of Decision: 0022/21 /TPA Ap: Mr Lougheed 10/02/2021 00:00:00Pine Lodge, Carlton Road, 03-Mar-2021 07/04/2021 00:00:00 Manby, Lincolnshire Ap: Pine Lodge Carlton Road Manby Lincolnshire LN11 8UF Ag: Summary of Proposed Work T15 - Ash - Fell. Conditions: Date Of Appeal: Details of Appeal: Date of Decision: Details of Decision: 0018/21 /TPA Ap: Mrs Sheldon 09/02/2021 00:00:00Quorndon, Parklands, 02-Mar-2021 06/04/2021 00:00:00 Mumby, Lincolnshire Ap: Quorndon Parklands Mumby Lincolnshire LN13 9SP Ag: Summary of Proposed Work G1 - 20 Sycamore & 1 Horse Chestnut - Sycamore - T1 on plan - Reduce crown by 2m all round to leave a radius of no less than 4m and a height of no less than 11m. -

Online Appendix Of: Rage Against the Machines: Labor-Saving Technology and Unrest in Industrializing England

Online Appendix of: Rage Against the Machines: Labor-Saving Technology and Unrest in Industrializing England Bruno Caprettini and Hans-Joachim Voth February 18, 2020 1 A Data appendix In this appendix, we describe all the steps that are necessary to create the dataset used in our analysis. A.1 Dataset construction To construct our database, we start from the map of ancient parishes of England and Wales prepared by Southall and Burton(2004). This map derives from earlier electronic maps by Kain and Oliver(2001), and contains a GIS database of all parishes of England and Wales in 1851. It consists of 22,729 separate polygons, each identifying a separate location. These are smaller than a parish, so that a given parish is often composed of several polygons. Because we observe all our variables at the parish level, we start by aggregating the 22,729 polygons into 11,285 parishes.1 Next, we aggregate a subset of these parishes into larger units of observation. We do this in two cases. First, large urban areas such as London, Liverpool or Manchester consists of several distinct parishes. Treating these areas as separate observations is incorrect, because we always observe riots and threshing machines for a whole city, and we generally not able to assign them to any specific area within a city. Thus, all parishes belonging to a city form a single observation. We also aggregate different parishes into larger units when the information from at least one of our sources does not allow us to compute one of our variables more precisely. -

Lincolnshire Remembrance User Guide for Submitting Information

How to… submit a war memorial record to 'Lincs to the Past' Lincolnshire Remembrance A guide to filling in the 'submit a memorial' form on Lincs to the Past Submit a memorial Please note, a * next to a box denotes that it needs to be completed in order for the form to be submitted. If you have any difficulties with the form, or have any questions about what to include that aren't answered in this guide please do contact the Lincolnshire Remembrance team on 01522 554959 or [email protected] Add a memorial to the map You can add a memorial to the map by clicking on it. Firstly you need to find its location by using the grab tool to move around the map, and the zoom in and out buttons. If you find that you have added it to the wrong area of the map you can move it by clicking again in the correct location. Memorial name * This information is needed to help us identify the memorial which is being recorded. Including a few words identifying what the memorial is, what it commemorates and a placename would be helpful. For example, 'Roll of Honour for the Men of Grasby WWI, All Saints church, Grasby'. Address * If a full address, including post code, is available, please enter it here. It should have a minimum of a street name: it needs to be enough information to help us identify approximately where a memorial is located, but you don’t need to include the full address. For example, you don’t need to tell us the County (as we know it will be Lincolnshire, North Lincolnshire or North East Lincolnshire), and you don’t need to tell us the village, town or parish because they can be included in the boxes below. -

Lincolnshire and the Danes

!/ IS' LINCOLNSHIRE AND THE DANES LINCOLNSHIRE AND THE DANES BY THE REV. G. S. STREATFEILD, M.A. VICAR OF STREATHAM COMMON; LATE VICAR OF HOLY TRINITY, LOUTH, LINCOLNSHIRE " in dust." Language adheres to the soil, when the lips which spake are resolved Sir F. Pai.grave LONDON KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH & CO., r, PATERNOSTER SQUARE 1884 {The rights of translation and of reproduction arc reserved.) TO HER ROYAL HIGHNESS ALEXANDRA, PRINCESS OF WALES, THIS BOOK IS INSCRIBED BY HER LOYAL AND GRATEFUL SERVANT THE AUTHOR. A thousand years have nursed the changeful mood Of England's race,—so long have good and ill Fought the grim battle, as they fight it still,— Since from the North, —a daring brotherhood,— They swarmed, and knew not, when, mid fire and blood, made their or took their fill They —English homes, Of English spoil, they rudely wrought His will Who sits for aye above the water-flood. Death's grip is on the restless arm that clove Our land in twain no the ; more Raven's flight Darkens our sky ; and now the gentle Dove Speeds o'er the wave, to nestle in the might Of English hearts, and whisper of the love That views afar time's eventide of light PREFACE. " I DO not pretend that my books can teach truth. All I hope for is that they may be an occasion to inquisitive men of discovering truth." Although it was of a subject infinitely higher than that of which the following pages treat, that Bishop Berkeley wrote such words, yet they exactly express the sentiment with which this book is submitted to the public. -

Highways Works Programme 2020-21

Highways Works Programmes 2020-21 Parish Location Work Type Traffic Management Programme Dates Alford Town Centre Street lighting works To be agreed Spring 2020 Bardney C502 Bardney Road Carriageway replacement Road closure April - October Beesby Beesby Pinfold Lane Drainage repairs To be agreed To be agreed Bilsby Bilsby Sutton Rd Drainage repairs To be agreed To be agreed Binbrook Binbrook Louth Rd Footway maintenance To be agreed To be agreed Boston Penn Street Carriageway replacement Road closure April - October Boston Red Cap Lane Carriageway replacement Road closure April - October Boston Wide Bargate Carriageway replacement Road closure April - October Boston C849 Town Bridge Repaint below deck Lane closure May 2020 Boston Matthew Flinders Way Area Street lighting works To be agreed Autumn/Winter 2020 Boston Sleaford Road/Brothertoft Road Traffic signals maintenance To be agreed Summer school holiday Boston Boston Amberley Crescent Footway maintenance To be agreed To be agreed Boston Boston Arundle Crescent Footway maintenance To be agreed To be agreed Boston Horncastle Road Footway maintenance To be agreed To be agreed Burgh on Bain Main Road at Village Store Drainage repairs To be agreed To be agreed Caistor C248 North Kelsey Road Carriageway replacement Road closure To be agreed Caistor Town Centre Street lighting works To be agreed Spring 2020 Carlton Le Moorland Main Road Junction Carriageway replacement Road closure To be agreed Carlton Le Moorland Navenby Lane Carriageway replacement Road closure To be agreed Carlton Scroop -

Saltfleetby – Theddlethorpe Dunes National Nature Reserve Welcome to Saltfleetby – Theddlethorpe Dunes Nature Reserve

Saltfleetby – Theddlethorpe Dunes National Nature Reserve Welcome to Saltfleetby – Theddlethorpe Dunes Nature Reserve Saltfleetby – Theddlethorpe Dunes stretches for 8 km along the north-east coast of Lincolnshire. Its constantly changing habitats, shaped by the wind and sea, are home to a wealth of plants, birds and insects. Although this wild area is the result of natural processes, it has been influenced over time by man. The site was purchased by the Air Ministry for use as a bombing range in the 1930s, and the beach was littered with old vehicles which were used as targets. During the Second World War tank traps and pillboxes were built, and the dunes were mined to defend against invasion. In 1969, part of the site was handed over to the Nature Conservancy and declared a National Nature Reserve (NNR). The bombing range eventually moved to Donna Nook in 1973. © Natural England © Natural Saltmarsh rainbow The Dunes bugloss to become established. These in turn support an array of bees and The sand dunes we see today first began butterflies. The smaller insects are hunted to form in the thirteenth century after by dragonflies and robber-flies that some unusually large storms. The sea patrol the dunes. Prickly sea buckthorn, threw up shingle and strong winds blew hawthorn and elder cover much of the sand to the back of the beach. This dunes and is an important habitat on this process continues today, creating new coastline. It provides safe cover and a shingle ridges, dunes and saltmarsh. nesting site for birds, including dunnocks and wrens, as well as summer visitors, The sand at Saltfleetby is very fine and including whitethroats and willow is easily blown off the beach onto the warblers. -

692 Art Trade~

692 ART TRADE~. [ LI~ COL ~SHIRE. ARCHITECTS continued. Harding J. 27 Fleetgate, Barton-on- ASSESSORS OF FIRE tRowell James, Church lane, Boston Humber LOSSES. Rudkin H. C. 19 Swinegate, Granthm Hardy Edward,2p., Market pl. Sleafrd Dickinson, Riggall & Davy, Old tScaping H. C. Town Hall11q.Grmsby Keeling Wm. B. 3 Eastgate, Louth Market place, Grimsby; also at tScorer & Gamble, Bank Street cham- Ketteringham Henry';156 High street, Louth & Market place, Brigg bers, Bank street, Lincoln Scunthorpe, Doncaster; Scatter, Longsta:II Richard & Co. Sheep Scorer William A.R.I.B.A. (firm, Lincoln-(&; thurs.) Market pl.Brigg market, Spalding Scorer & Gamble) Kettleborough A. 88 West pa.r.Lincoln Longsta:II & Wadsley, West st.Bourne Thropp & Harding, 29 Broadgate,Lncln McCarthy Charles John, 42 Hainton t'l'raylen Hy.Fras.16 Broad st.Stamfd avenue, Grimsby ASSOCIATIONS. Wadslej Robert, Station road,Billing- Manning (H.) & Miller, 86 Upgate, See Societies & Associations. borough, Folkingham Louth ; & at Alford & I Banks st. ATHLETIC OUTFITTERS. Walker Herbert & Son, IS Southgate, Horncastle Sleaford Newton & Holden Limited, 28 Tenter Ives Wm. 3 & 4 Guildhall st.Lin~:oln tWard J. T. 6 Ironmonger st.Stamford croft street, Lincoln· & (attends Lincoln Cycle Co. 4 Corporation st_ Watkin9 William F.R.I.:B.A. & Son mon.) 36 Southgate, Sleaford Lincoln A.R.I.B.A. Bank street, Lincoln Parker Harry, 2·I Spilsby rd. Boston Parker Charles, Ig Market place, Louth Peck Wm. 2 Spital ter. Gainsborough Sports Supply Co. sac, Pasture st. ART FURNITURE MANFRS. Renals F. W. T. Cavendish road & Grimsby Harrison W. B. & Sons (willow, cane Roman bank, Skegness Starsmore & Co.