IN the MATTER and of the Resource Management Act 1991 in THE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waikato 2070

WAIKATO 2070 WAIKATO DISTRICT COUNCIL Growth & Economic Development Strategy 2 3 Waikato 2070 Waikato WELCOME TO THE WAIKATO DISTRICT CONTENTS The Waikato District Council Growth & Economic Development Strategy WAIKATO DISTRICT COUNCIL: GROWTH & ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY DISTRICT GROWTH DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL: & ECONOMIC WAIKATO (Waikato 2070) has been developed to provide guidance on appropriate 01.0 Introduction 4 growth and economic development that will support the wellbeing of the district. 02.0 Our Opportunities 13 This document has been prepared using the Special Consultative Procedure, Section 83, of the Local Government Act (2002). 03.0 Focus Areas 19 WHAT IS THE GROWTH STRATEGY? 04.0 Our Towns 25 A guiding document that the Waikato District Council uses to inform how, where and when growth occurs in the district over the next 50-years. The growth indicated in Waikato 2070 has been informed by in-depth analysis 05.0 Implementation 43 and combines economic, community and environmental objectives to create liveable, thriving and connected communities. The growth direction within Waikato 2070 will ultimately inform long-term planning and therefore affect 06.0 Glossary 46 social, cultural, economic and environmental wellbeing. WHAT DOES IT COVER? The strategy takes a broad and inclusive approach to growth over the long term, taking into account its economic, social, environmental, cultural and physical dimensions. Waikato 2070 is concerned with the growth and development of communities throughout the district, including rural and urban environments. Adopted by Waikato District Council 19 May 2020. VERSION: 16062020 REGION WIDE Transport connections side/collector main/arterial highway (state highways, arterials, rail) Future mass-transit stations rail and station short-term medium/long-term (and connections into Auckland, Hamilton, Waipa) Industrial Clusters Creative Ind. -

201102 CCL Open Agenda

1 Agenda for a meeting of the Waikato District Council to be held in the Council Chambers, District Office, 15 Galileo Street, Ngaruawahia on MONDAY, 2 NOVEMBER 2020 commencing at 9.30am. Information and recommendations are included in the reports to assist the Council in the decision-making process and may not constitute Council’s decision or policy until considered. 1. APOLOGIES AND LEAVE OF ABSENCE 2. CONFIRMATION OF STATUS OF AGENDA 3. DISCLOSURES OF INTEREST 4. CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES 4.1 Minutes of a Council meeting held on 21 September 2020 5 4.2 Minutes of an Extraordinary Council meeting held on 28 September 2020 12 5. COMMITTEE REPORTS 5.1 Policy & Regulatory Committee Committee Recommendations to Council – 12 October 2020 16 5.2 Strategy & Finance Committee Committee Recommendations to Council – 13 October 2020 17 6. REPORTS 6.1 Zero Harm Update 18 6.2 Mana Whenua Forums 24 6.3 Maaori Wards 28 6.4 Delegations to Watercare Services Limited 40 6.5 Council and Committee 2021 Meeting Calendar 48 6.6 Sale of Vehicle – 2017 Toyota Highlander KPT7 51 Waikato District Council 1 Agenda: 2 November 2020 2 7. EXCLUSION OF THE PUBLIC 55 GJ Ion CHIEF EXECUTIVE Waikato District Council 2 Agenda: 2 November 2020 3 TERMS OF REFERENCE AND DELEGATION Chairperson: His Worship the Mayor Deputy Chairperson: Deputy Mayor Membership: The Mayor and all Councillors Meeting frequency: Six weekly – or as required Quorum: Half of the members (including vacancies) Purpose 1. To provide leadership to, and advocacy on behalf of, the people of the Waikato District. -

Monthy Grant Summary April 2019-Feb 2020 .Xlsx

Organisation Name TLA Amount Requested Allocated Amount WAIKATO / BOP Kauaeranga Hall Society Inc Thames-Coromandel District Council $12,112.00 $7,500.00 University of Waikato Rugby Club Inc Hamilton City Council $15,000.00 $7,500.00 CCS Disability Action Waikato Inc Hamilton City Council $15,000.00 $15,000.00 Hamilton Inline Hockey Club Inc Hamilton City Council $109,297.60 $10,000.00 N Z P F - Edgecumbe Playcentre Whakatane District Council $28,254.13 $8,653.00 Bowls Tauranga South Inc Tauranga City Council $32,000.00 $15,000.00 Waikato Rocks Trust Hamilton City Council $30,000.00 $10,000.00 Putaruru College South Waikato District Council $3,876.00 $3,386.00 T F K A - Frankleigh Park Kindergarten New Plymouth District Council $4,140.00 $3,600.00 Awakeri Primary School Whakatane District Council $12,200.00 $12,200.00 Fitzroy Golf Club Inc New Plymouth District Council $2,545.00 $2,545.00 Waterpolo Rotorua Club Inc Rotorua District Council $31,920.00 $5,000.00 Merrilands School New Plymouth District Council $5,000.00 $5,000.00 Te Puru School Thames-Coromandel District Council $4,820.82 $4,820.00 Liz Van Welie Aquatics Swimming Club Inc Tauranga City Council $15,960.00 $5,000.00 Thames Community Centre Trust Thames-Coromandel District Council $6,000.00 $4,000.00 Balloons Over Waikato Charitable Trust Hamilton City Council $20,280.00 $10,000.00 Sri Lanka Friendship Soc Waikato Inc Hamilton City Council $6,000.00 $2,500.00 Athletics Taranaki Inc New Plymouth District Council $12,200.00 $8,000.00 Melville Cricket Club Inc Hamilton City Council -

Tata Valley Limited

Before an Independent Hearings Panel The Proposed Waikato District Plan (Stage 1) IN THE MATTER OF the Resource Management Act 1991 (RMA) IN THE MATTER OF hearing submissions and further submissions on the Proposed Waikato District Plan (Stage 1): Topic 25 – Zone Extents PRIMARY EVIDENCE OF CHRISTOPHER JAMES SCRAFTON ON BEHALF OF TATA VALLEY LIMITED 19 February 2021 Barristers and Solicitors Auckland Solicitor Acting: Vanessa Evitt / Mathew Gribben Email: [email protected] / [email protected] Tel 64-9-358 2555 PO Box 1433 DX CP24024 Auckland 1140 1. SUMMARY OF EVIDENCE 1.1 The vision of TaTa Valley Limited (TVL) is to develop the Site at 242 Bluff Road1 and 35 Trig Road, Pokeno into the TaTa Valley Resort. The Tata Valley Resort comprises a Hotel and Farm Park with associated tourism, retail and recreation activities that showcases rural New Zealand. Key activities proposed as part of the Resort include a hotel with amenities such as a conference and event space, camping/glamping throughout the Site, a ‘New Zealand Made Hub’ (NZ Hub) to showcase rural New Zealand and other recreational activities. 1.2 In my view, and as discussed in more detail in Appendix B, a special purpose zone is a more efficient and effective method than the alternative of developing the Site than (for example) the Rural Zone given: (a) That while the proposal requires a rural environment to operate, the objectives and policies of the Rural Zone are necessarily broad and relate to the entire Rural Zone and do not sufficiently enable the development of the Site as proposed; (b) Similarly, a number of activities proposed as part of the Resort Zone are not adequately provided for in the Rural Zone; (c) The proposal is distinct and does not fit well with any traditional land use zoning. -

Local Government Leaders' Climate Change Declaration

Local Government Leaders’ Climate Change Declaration In 2015, Mayors and Chairs of New Zealand declared an urgent need for responsive leadership and a holistic approach to climate change. We, the Mayors and Chairs of 2017, wholeheartedly support that call for action. Climate change presents significant opportunities, challenges and risks to communities throughout the world and in New Zealand. Local and regional government undertakes a wide range of activities that will be impacted by climate change and provides infrastructure and services useful in reducing greenhouse gas emissions and enhancing resilience. We have come together, as a group of Mayors and Chairs representing local government from across New Zealand to: 1. acknowledge the importance and urgent need to address climate change for the benefit of current and future generations; 2. give our support to the New Zealand Government for developing and implementing, in collaboration with councils, communities and businesses, an ambitious transition plan toward a low carbon and resilient New Zealand; 3. encourage Government to be more ambitious with climate change mitigation measures; 4. outline key commitments our councils will take in responding to the opportunities and risks posed by climate change; and 5. recommend important guiding principles for responding to climate change. We ask that the New Zealand Government make it a priority to develop and implement an ambitious transition plan for a low carbon and resilient New Zealand. We stress the benefits of early action to moderate the costs of adaptation to our communities. We are all too aware of challenges we face shoring up infrastructure and managing insurance costs. -

Pdf 190925 SF Open Agenda Pdf, 10569 KB Download

1 Agenda for a meeting of the Strategy & Finance Committee to be held in the Council Chambers, District Office, 15 Galileo Street, Ngaruawahia on WEDNESDAY 25 SEPTEMBER 2019 commencing at 9.00am. Information and recommendations are included in the reports to assist the Committee in the decision making process and may not constitute Council’s decision or policy until considered by the Committee. 1. APOLOGIES AND LEAVE OF ABSENCE 2. CONFIRMATION OF STATUS OF AGENDA 3. DISCLOSURES OF INTEREST 4. CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES Meeting held on 28 August 2019 3 5. RECEIPT OF AUDIT & RISK COMMITTEE MINUTES Meeting held on 27 June 2019 12 6. STRATEGY REPORTS 6.1 Adoption of Waikato District Council Library Strategy 22 6.2 Notice of Requirement for Rotokauri Greenway Stormwater Designation 51 7. FINANCE REPORTS 7.1 Funding for Karioitahi Hall 59 7.2 Financial Performance Summary for the period ending 31 August 2019 62 7.3 Local Government Funding Agency Annual Report 2019 64 7.4 Approved Counterparty Review 150 7.5 Council Controlled Organisations Annual Reports 151 Waikato District Council Strategy & Finance Committee 1 Agenda: 25 September 2019 2 7.6 Presentation of the Annual Report and Summary 2018/19 (Annual Report & Summary Attachment to be circulated under separate cover) 224 8. EXCLUSION OF THE PUBLIC 228 GJ Ion CHIEF EXECUTIVE Waikato District Council Strategy & Finance Committee 2 Agenda: 25 September 2019 3 Open Meeting To Strategy & Finance Committee From Gavin Ion Chief Executive Date 16 September 2019 Prepared by Lynette Wainwright Committee Secretary Chief Executive Approved Y Reference # GOV1301 Report Title Confirmation of Minutes – 28 August 2019 1. -

Long Term Plan 2018-28 Te Whakamahere Whaaroa 2018-28 Contents

Long Term Plan 2018-28 Te Whakamahere Whaaroa 2018-28 Contents Our Vision: Liveable, Thriving, Connected Communities 4 Our Community Outcomes and Goals 4 Key Decisions 5 Financial strategy 6 Balancing Affordability and Growth 6 Sustainable Growth 6 Maintaining Existing Assets 7 Better Services 8 Managing Debt 9 Affordable Rates 10 Balancing the Books 10 Good Investments 11 Planning for the Unexpected 12 30 Year Infrastructure Strategy (2018 – 2048) 13 Strategic Alignment 13 Context 14 Activity Management Practices 18 Strategic Issues and Significant Decisions 23 Most Likely Scenario 31 Key Infrastructure Activities 34 Water supply 34 Wastewater 36 Stormwater drainage 38 Roads and footpaths 40 Solid waste 42 Parks 44 Properties and facilities 46 Libraries 47 The Waikato Spatial Plan 49 Waikato: he reo kotahi 49 Significant Forecasting Assumptions 50 What we do 63 Governance 65 Sustainable Environment 68 Sustainable Communities 77 2 WAIKATO DISTRICT COUNCIL | Long Term Plan 2018-28 Roading 86 Stormwater 90 Wastewater 95 Water Supply 99 Organisational Support 105 Funding Impact Statement 107 Rating Base Information 113 Financial Planning 120 Long Term Plan Disclosure statement 131 Statement of Accounting Policies 134 Reporting entity 134 Basis of preparation 134 Significant Accounting Policies 135 Employee entitlements 142 Policies and Plans 145 Significance and Engagement Policy 145 Revenue and Finance Policy 145 Rate remission and postponement policies 150 Remission of Penalties 150 Remission & Postponement Policy – Maaori Freehold Land -

Agenda for a Meeting of the Strategy & Finance Committee to Be Held In

1 Agenda for a meeting of the Strategy & Finance Committee to be held in the Council Chambers, District Office, 15 Galileo Street, Ngaruawahia on WEDNESDAY, 5 FEBRUARY 2020 commencing at 9.30am. 1. APOLOGIES AND LEAVE OF ABSENCE 2. CONFIRMATION OF STATUS OF AGENDA 3. DISCLOSURES OF INTEREST 4. CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES Meeting held on Monday, 2 December 2019 2 5. STRATEGY REPORTS 5.1 Climate Response Planning 9 5.2 Economic and Community Development Update 87 6. FINANCE REPORTS 6.1 Financial performance summary for the period ending 31 December 2019 98 6.2 Treasury Risk Management Policy – Compliance Report at 31 December 2019 104 6.3 Council Credit Rating 111 6.4 Civic Financial Services - Statement of Intent for 2020 127 7. EXCLUSION OF THE PUBLIC 134 GJ Ion CHIEF EXECUTIVE Waikato District Council Strategy & Finance Committee 1 Agenda: 5 February 2020 2 Open Meeting To Strategy & Finance Committee From Gavin Ion Chief Executive Date 12 December 2019 Prepared by Lynette Wainwright Committee Secretary Chief Executive Approved Y Reference # GOV1301 Report Title Confirmation of Minutes 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY To confirm the minutes of the Strategy & Finance Committee meeting held on Monday, 2 December 2019. 2. RECOMMENDATION THAT the minutes of the meeting of the Strategy & Finance Committee held on Monday, 2 December 2019 be confirmed as a true and correct record of that meeting. 3. ATTACHMENTS S&F Committee Minutes – 2 December 2019 Page 1 Version 4.0 3 Minutes of a meeting of the Strategy & Finance Committee of the Waikato District Council held in the Council Chambers, District Office, 15 Galileo Street, Ngaruawahia on MONDAY 2 DECEMBER 2019 commencing at 9.30am. -

190909 Council Open Agenda

1 Agenda for a meeting of the Waikato District Council to be held in the Council Chambers, District Office, 15 Galileo Street, Ngaruawahia on MONDAY 9 SEPTEMBER 2019 commencing at 1.00pm. Information and recommendations are included in the reports to assist the Committee in the decision making process and may not constitute Council’s decision or policy until considered by the Committee. 1. APOLOGIES AND LEAVE OF ABSENCE 2. CONFIRMATION OF STATUS OF AGENDA 3. DISCLOSURES OF INTEREST 4. CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES 4.1 Minutes of a Council meeting held on Monday, 12 August 2019 3 4.2 Minutes of an Extraordinary Council meeting held on Wednesday, 14 August 2019 14 5. COMMITTEE AND DEPARTMENTAL REPORTS 5.1 Policy & Regulatory Committee 5.1.1 Receipt of Committee Minutes – 18 June 2019 18 5.1.2 Committee Recommendations to Council - 20 August 2019 23 5.1.3 Zero Harm 24 5.2 Strategy & Finance Committee 5.2.1 Receipt of Committee Minutes – 26 June 2019 32 5.2.2 Committee Recommendations to Council – 28 August 2019 38 5.3 Infrastructure Committee 5.3.1 Receipt of Committee Minutes – 25 June 2019 39 5.3.2 Committee Recommendations to Council – 27 August 2019 45 Waikato District Council 1 Agenda: 9 September 2019 2 5.4 Discretionary & Funding Committee 5.4.1 Receipt of Committee Minutes – 13 May 2019 48 5.5 Other Committees and Decision-Making Bodies 5.5.1 Minutes of the Waters Governance Board – 24 July 2019 54 5.5.4 Minutes of the Waikato Raupatu River Trust1 and Waikato District Council Joint Committee - 24 April 2019 58 6. -

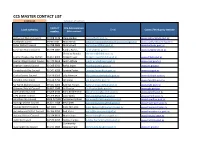

CCS MASTER CONTACT LIST 2/08/2021 1St Point of Contact

CCS MASTER CONTACT LIST 2/08/2021 1st point of contact Contact CCS Administrator Local authority Email Council/third party website number (Main contact) Ashburton District Council 03 308 5139 Clare Harden [email protected] www.ashburtondc.govt.nz Auckland Council 09 3010101 Mary Borok [email protected] www.aucklandcouncil.govt.nz Buller District Council 03 788 9683 Mira Schwill [email protected] www.bullerdc.govt.nz Carterton District Council 06 379 4081 Sandra Burles [email protected] www.cartertondc.co.nz Christine Renata [email protected] Central Hawkes Bay District 06 857 8060 Bridget Cover [email protected] www.chbdc.govt.nz Central Otago District Council 03 440 0618 Judith Whyte [email protected] www.codc.govt.nz Chatham Islands Council 03 305 0033 Barby Joyce [email protected] www.cic.govt.nz Christchurch City Council 03 941 6288 Lynette Foster [email protected] www.ccc.govt.nz Clutha District Council 03 419 0200 Lilly Paterson [email protected] www.cluthadc.govt.nz Dunedin City Council 03 474 3792 Jen Lucas [email protected] www.dunedin.govt.nz Far North District Council 09 401 5200 Kathryn Trewin [email protected] www.fndc.govt.nz Gisborne District Council 06 867 2049 Liz Proctor [email protected] www.gdc.govt.nz Gore District Council 03 209 0330 Karla Brotherston [email protected] www.goredc.govt.nz Grey District Council 03 769 8600 Leah Smith [email protected] www.greydc.govt.nz Hamilton City Council -

Waikato District Plan Review Technical Responses to Submissions Relating to Ecology

Waikato District Council Waikato District Plan Review Technical responses to submissions relating to ecology Contact Details Caitlin Dodunski WSP Opus House, Princes Street, Hamilton 3204 Private Bag 3057, Waikato Mail Centre, Hamilton 3240 +64 7 838 9344 +64 21 514 331 [email protected] Document Details: Date: 14 October 2020 Reference: Status: Final Prepared by John Turner Reviewed by Claire Cunningham ©WSP New Zealand Limited 2020 i Document History and Status Revision Date Author Reviewed by Status 1 14 October 2020 John Turner Claire Cunningham Final Revision Details Revision Details ©WSP New Zealand Limited 2020 ii Contents Disclaimers and Limitations .................................................................................................................................................................................. 1 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................................................ 2 2 Bats ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 2.1 Submissions .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 2.2 Bats in the Waikato District.................................................................................................................................................... -

Agenda for a Meeting of the Infrastructure Committee to Be Held

1 Agenda for a meeting of the Infrastructure Committee to be held in the Council Chambers, District Office, 15 Galileo Street, Ngaruawahia on MONDAY, 27 JULY 2020 commencing at 9.30am. Information and recommendations are included in the reports to assist the committee in the decision making process and may not constitute Council’s decision or policy until considered by the committee. 1. APOLOGIES AND LEAVE OF ABSENCE 2. CONFIRMATION OF STATUS OF AGENDA 3. DISCLOSURES OF INTEREST 4. CONFIRMATION OF MINUTES Meeting held on Monday, 15 June 2020 4 5. REPORTS 5.1 Sport Waikato Report – 1 April 2020 to 30 June 2020 11 5.2 Service Delivery Report for July 2020 21 5.3 Road Name Approval – Maataitai Street second phase in the Rangitahi Development, Raglan 44 5.4 Partial Stopping of Annebrook Road, Tamahere 53 5.5 Partial Stopping of Glen Murray Road 70 5.6 Petition to Council to Purchase the Land at Pukeiahua Pa (Petition document will be separate to the agenda) 77 5.7 Road Efficiency Group Road Controlling Authority Reports 81 6. EXCLUSION OF THE PUBLIC 96 GJ Ion CHIEF EXECUTIVE Waikato District Council Infrastructure Committee 1 Agenda: 27 July 2020 2 TERMS OF REFERENCE AND DELEGATION Reports to: The Council Chairperson: Cr Eugene Patterson Deputy Chairperson: Cr Carolyn Eyre Membership: The Mayor, all Councillors and Mr Brendon Green Meeting frequency: Six-weekly Quorum: Majority of the members (including vacancies)1 Purpose The Infrastructure Committee is responsible for: 1. Guiding sustainable, physical development and growth of the Council’s infrastructure to meet current and future needs.