Tina Theory: Notes on Fierceness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Passionate Pursuits

Fall/Winter ’08/’09 Passionate Pursuits Friends’ Central Directions Fall/Winter ’08/’09 2008-2009 Board of Trustees From the Headmaster: Ann V. Satterthwaite, Clerk Peter P. Arfaa James B. Bradbeer, Jr. Adrian Castelli Dear Friends, Kenneth Dunn Kaye Edwards I have just finished previewing the George Elser feature articles for this edition of Jean Farquhar ’70 Victor Freeman ’80 Directions, and if you can set aside the Christine Gaspar ’70 time, I believe you will be as fascinated as Robert Gassel ’69 I have been by the collecting passions of Edward Grinspan William Fordyce ’52, Joanna Schoff ’51, Walter Harris ’75 Sally Harrison Rich Ulmer ’60, Rachel Newmann Karen Horikawa ’77 Schwartz ’89, and current student Blake Deborah Hull Bortnick ’13. In her introduction, our Michael C. Kelly editor, Rebecca Anderson, sheds some Matthew S. Levitties ’85 Craig Lord light on possible motives for collecting Hillard Madway and provides additional examples of col - Ed Marshall ’68 lectors currently devoting time and effort Carol Mongeluzzi Suzanne Morrison to a favorite pastime in the School’s midst By all accounts, William Fordyce was Jeffrey Purdy and for our community’s benefit. The a very private man, and after his gradua - Lawrence S. Reichlin interest a collector displays in sharing a tion he was mainly absent from our com - Marsha Rothman collection is particularly gratifying to a munity. In the end, though, through his Jonathan Sprogell James Wright School that both encourages and sup - thoughtful and generous gift he returned Barbara M. Cohen, Emerita ports individual interests and values to the School and revealed an important Joanna Haab Schoff ’51, Emerita connections among members of the part of himself. -

Not Your Mother's Library Transcript Episode 11: Mamma Mia! and More Musicals (Brief Intro Music) Rachel: Hello, and Welcome T

Not Your Mother’s Library Transcript Episode 11: Mamma Mia! and More Musicals (Brief intro music) Rachel: Hello, and welcome to Not Your Mother’s Library, a readers’ advisory podcast from the Oak Creek Public Library. I’m Rachel, and once again since Melody’s departure I am without a co-host. This is where you would stick a crying-face emoji. Luckily for everyone, though, today we have a brand new guest! This is most excellent, truly, because we are going to be talking about musicals, and I do not have any sort of expertise in that area. So, to balance the episode out with a more professional perspective, I would like to welcome to the podcast Oak Creek Library’s very own Technical Services Librarian! Would you like to introduce yourself? Joanne: Hello, everyone. I am a new guest! Hooray! (laughs) Rachel: Yeah! Joanne: So, I am the Technical Services Librarian here at the Oak Creek Library. My name is Joanne. I graduated from Carroll University with a degree in music, which was super helpful for libraries. Not so much. Rachel: (laughs) Joanne: And then went to UW-Milwaukee to get my masters in library science, and I’ve been working in public libraries ever since. I’ve always had a love of music since I've been in a child. My mom is actually a church organist, and so I think that’s where I get it from. Rachel: Wow, yeah. Joanne: I used to play piano—I did about 10 years and then quit. (laughs) So, I might be able to read some sheet music but probably not very well. -

Dickins' Sony Deal Opens New Chapter by Ajax Scott Rob Dickins Bas Teame Former Rival Sony Music Three Months After Leaving Warn

Dickins' Sony deal opens new chapter by Ajax Scott later building a team of up to 20. Rob Dickins bas teame Instant Karma will sign around five rA, ^ threeformer months rival Sony after Music leaving warner ri likelyartists to a be year, from most the UKof orwhom Ireland. are hisMusic music to launchindustry the career. next stage of Dickins says he will not specifically S Dickins' new record label Instant goclose chasing to expiring. after those Tm notacts. going If they to with the hasfirst got single off torelease a fiying under start the handling partnership Interscope - My releasesName Is inby the US UK they'reare interested going to in call," being he part says. of that therapper single, Eminem released - enjoying next Monday a huge initial(March shipout. 29), have Around been 220.000 ordered unitsby of months of negotiations between runningDickins, Warner's who spent UK ninepublishing years theretaiiefsVwhile Top 40 of the the Airplay track waschart. yesterday "Ifs appealing (Sunday) right on acrosscourse theto move board," into says Dickins, his lawyer Tony Russell arm before moving to head its Polydor head of radio promotionl" TU.Ruth ..U.._ Parrish. A V.UK promo visit will inelude wasand afinaliy list of whittled would-be down backers to Sony that New partners: Dickins (second isrecord in no company hurry toin 1983,issue addsrecords. he im_ rrShady LPes - thiswhich week debuted on The at Bignumber Breakfast twoThe in and the CD:UK.States earlierThe this (l-r)left) Sony in New Music York Worldwide last week with "Ifs really not important when the onth - follows on April 12. -

Popular Love Songs

Popular Love Songs: After All – Multiple artists Amazed - Lonestar All For Love – Stevie Brock Almost Paradise – Ann Wilson & Mike Reno All My Life - Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville Always and Forever – Luther Vandross Babe - Styx Because Of You – 98 Degrees Because You Loved Me – Celine Dion Best of My Love – The Eagles Candle In The Wind – Elton John Can't Take My Eyes off of You – Lauryn Hill Can't We Try – Vonda Shepard & Dan Hill Don't Know Much – Linda Ronstadt & Aaron Neville Dreaming of You - Selena Emotion – The Bee Gees Endless Love – Lionel Richie & Diana Ross Even Now – Barry Manilow Every Breath You Take – The Police Everything I Own – Aaron Tippin Friends And Lovers – Gloria Loring & Carl Anderson Glory of Love – Peter Cetera Greatest Love of All – Whitney Houston Heaven Knows – Donna Summer & Brooklyn Dreams Hello – Lionel Richie Here I Am – Bryan Adams Honesty – Billly Joel Hopelessly Devoted – Olivia Newton-John How Do I Live – Trisha Yearwood I Can't Tell You Why – The Eagles I'd Love You to Want Me - Lobo I Just Fall in Love Again – Anne Murray I'll Always Love You – Dean Martin I Need You – Tim McGraw & Faith Hill In Your Eyes - Peter Gabriel It Might Be You – Stephen Bishop I've Never Been To Me - Charlene I Write The Songs – Barry Manilow I Will Survive – Gloria Gaynor Just Once – James Ingram Just When I Needed You Most – Dolly Parton Looking Through The Eyes of Love – Gene Pitney Lost in Your Eyes – Debbie Gibson Lost Without Your Love - Bread Love Will Keep Us Alive – The Eagles Mandy – Barry Manilow Making Love -

Platinum Master Songlist

Platinum Master Songlist A B C D E 1 STANDARDS/ JAZZ VOCALS/SWING BALLADS/ E.L. -CONT 2 Ain't Misbehavin' Nat King Cole Over The Rainbow Israel Kamakawiwo'ole 3 Ain't I Good Too You Various Artists Paradise Sade 4 All Of Me Various Artists Purple Rain Prince 5 At Last Etta James Say John Mayer 6 Blue Moon Various Artists Saving All My Love Whitney Houston 7 Blue Skies Eva Cassidy Shower The People James Taylor 8 Don't Get Around Much Anymore Nat King Cole Stay With Me Sam Smith 9 Don't Know Why Nora Jones Sunrise, Sunset Fiddler On The Roof 10 Fly Me To The Moon Frank Sinatra The First Time ( Ever I Saw You Face)Roberta Flack 11 Georgia On My Mind Ray Charles Thinking Out Loud Ed Sheeren 12 Girl From Impanema Various Artists Time After Time Cyndi Lauper 13 Haven't Met You Yet Michael Buble' Trouble Ray LaMontagne 14 Home Michael Buble' Tupelo Honey Van Morrison 15 I Get A Kick Out Of You Frank Sinatra Unforgettable Nat King Cole 16 It Don’t Mean A Thing Various Artists When You Say Nothing At All Alison Krause 17 It Had To Be You Harry Connick Jr. You Are The Best Thing Ray LaMontagne 18 Jump, Jive & Wail Brian Setzer Orchestra You Are The Sunshine Of My Life Stevie Wonder 19 La Vie En Rose Louis Armstrong You Look Wonderful Tonight Eric Clapton 20 Let The Good Times Roll Louie Jordan 21 LOVE Various Artists 22 My Funny Valentine Various Artists JAZZ INSTRUMENTAL 23 Oranged Colored Sky Natalie Cole Birdland Joe Zawinul 24 Paper Moon Nat King Cole Breezin' George Benson 25 Route 66 Nat King Cole Chicago Song David Sanborn 26 Satin Doll Nancy Wilson Fragile Sting 27 She's No Lady Various Artists Just The Two Of Us Grover Washington Jr. -

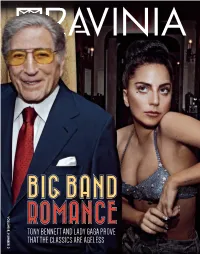

Tony Bennett and Lady Gaga Prove That the Classics Are

VOLUME 8, NUMBER 2 TONY BENNETT AND LADY GAGA PROVE THAT THE CLASSICS ARE AGELESS Untitled-2 2 5/27/15 11:56 AM Steven Klein 418 Sheridan Road Highland Park, IL 60035 847-266-5000 www.ravinia.org Welz Kauffman President and CEO Nick Pullia Communications Director, Executive Editor Nick Panfil Publications Manager, Editor Alexandra Pikeas Graphic Designer IN THIS ISSUE TABLE OF CONTENTS DEPARTMENTS 18 This Boy Does Cabaret 13 Message from John Anderson Since 1991 Alan Cumming conquers the world stage and Welz Kauffman 3453 Commercial Ave., Northbrook, IL 60062 with a “sappy” song in his heart. www.performancemedia.us 24 No Keeping Up 59 Foodstuff Gail McGrath Publisher & President Sharon Jones puts her soul into energetic 60 Ravinia’s Steans Music Institute Sheldon Levin Publisher & Director of Finance singing. REACH*TEACH*PLAY Account Managers 30 Big Band Romance 62 Sheryl Fisher - Mike Hedge - Arnie Hoffman Tony Bennett and Lady Gaga prove that 65 Lawn Clippings Karen Mathis - Greg Pigott the classics are ageless. East Coast 67 Salute to Sponsors 38 Long Train Runnin’ Manzo Media Group 610-527-7047 The Doobie Brothers have earned their 82 Annual Fund Donors Southwest station as rock icons. Betsy Gugick & Associates 972-387-1347 88 Corporate Partners 44 It’s Not Black and White Sales & Marketing Consultant Bobby McFerrin sees his own history 89 Corporate Matching Gifts David L. Strouse, Ltd. 847-835-5197 with Porgy and Bess. 90 Special Gifts Cathy Kiepura Graphic Designer 54 Swan Songs (and Symphonies) Lory Richards Graphic Designer James Conlon recalls his Ravinia themes 91 Board of Trustees A.J. -

Nielsen Music Year-End Report Canada 2016

NIELSEN MUSIC YEAR-END REPORT CANADA 2016 NIELSEN MUSIC YEAR-END REPORT CANADA 2016 Copyright © 2017 The Nielsen Company 1 Welcome to the annual Nielsen Music Year End Report for Canada, providing the definitive 2016 figures and charts for the music industry. And what a year it was! The year had barely begun when we were already saying goodbye to musical heroes gone far too soon. David Bowie, Leonard Cohen, Glenn Frey, Leon Russell, Maurice White, Prince, George Michael ... the list goes on. And yet, despite the sadness of these losses, there is much for the industry to celebrate. Music consumption is at an all-time high. Overall consumption of album sales, song sales and audio on-demand streaming volume is up 5% over 2015, fueled by an incredible 203% increase in on-demand audio streams, enough to offset declines in sales and return a positive year for the business. 2016 also marked the highest vinyl sales total to date. It was an incredible year for Canadian artists, at home and abroad. Eight different Canadian artists had #1 albums in 2016, led by Drake whose album Views was the biggest album of the year in Canada as well as the U.S. The Tragically Hip had two albums reach the top of the chart as well, their latest release and their 2005 best of album, and their emotional farewell concert in August was something we’ll remember for a long time. Justin Bieber, Billy Talent, Céline Dion, Shawn Mendes, Leonard Cohen and The Weeknd also spent time at #1. Break out artist Alessia Cara as well as accomplished superstar Michael Buble also enjoyed successes this year. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

Shoosh 800-900 Series Master Tracklist 800-977

SHOOSH CDs -- 800 and 900 Series www.opalnations.com CD # Track Title Artist Label / # Date 801 1 I need someone to stand by me Johnny Nash & Group ABC-Paramount 10212 1961 801 2 A thousand miles away Johnny Nash & Group ABC-Paramount 10212 1961 801 3 You don't own your love Nat Wright & Singers ABC-Paramount 10045 1959 801 4 Please come back Gary Warren & Group ABC-Paramount 9861 1957 801 5 Into each life some rain must fall Zilla & Jay ABC-Paramount 10558 1964 801 6 (I'm gonna) cry some time Hoagy Lands & Singers ABC-Paramount 10171 1961 801 7 Jealous love Bobby Lewis & Group ABC-Paramount 10592 1964 801 8 Nice guy Martha Jean Love & Group ABC-Paramount 10689 1965 801 9 Little by little Micki Marlo & Group ABC-Paramount 9762 1956 801 10 Why don't you fall in love Cozy Morley & Group ABC-Paramount 9811 1957 801 11 Forgive me, my love Sabby Lewis & the Vibra-Tones ABC-Paramount 9697 1956 801 12 Never love again Little Tommy & The Elgins ABC-Paramount 10358 1962 801 13 Confession of love Del-Vikings ABC-Paramount 10341 1962 801 14 My heart V-Eights ABC-Paramount 10629 1965 801 15 Uptown - Downtown Ronnie & The Hi-Lites ABC-Paramount 10685 1965 801 16 Bring back your heart Del-Vikings ABC-Paramount 10208 1961 801 17 Don't restrain me Joe Corvets ABC-Paramount 9891 1958 801 18 Traveler of love Ronnie Haig & Group ABC-Paramount 9912 1958 801 19 High school romance Ronnie & The Hi-Lites ABC-Paramount 10685 1965 801 20 I walk on Little Tommy & The Elgins ABC-Paramount 10358 1962 801 21 I found a girl Scott Stevens & The Cavaliers ABC-Paramount -

Announcing Our Summer Reading List!

Glass Sentence (The Mapmakers Trilogy book 1) by S.E. Grove Rising 7th Graders Boston, 1891. Sophia Tims comes from a family of explorers and cartologers Announcing Our Summer Reading List! who, for generations, have been traveling and mapping the New World—a Tangerine* - by Edward Bloor (required for students in Gifted world changed by the Great Disruption of 1799, when all the continents were program) “Paul Fisher's got a weird obsession with zombies. Or at least, he sure seems to. He and flung into different time periods. Eight years ago, Sophia's parents left her his family are moving from Houston to Tangerine County, Florida, and all he can think Our Language Arts Teachers, Media Specialist, and Literacy Coach have with her uncle Shadrack, the foremost cartologer in Boston, and went on an about is how his old house reminds him of an empty zombie tomb. Dude's got some real chosen some exciting books for our students to read this summer. We have come urgent mission. They never returned. fond memories of his childhood home, there.” - Shmoop Editorial Team. "Tangerine Summary." Shmoop. up with a list of suggested books and authors for each grade level. Students will Shmoop University, Inc., 11 Nov. 2008. Web. 22 May 2018. be held accountable for reading two books from their rising grade level list of books Skink – No Surrender – Carl Hiaasan and authors over the summer. They will be assessed by the Language Arts Ghost – (Book 1) Jason Reynolds Department during the first month of the 2019-2020 school year. This assessment When your cousin goes missing under suspicious circumstances, who Castle “Ghost” Cranshaw is an African-American teenager growing up in the projects with will become an important part of their first quarter Language Arts grade. -

Jazz Documentary

Jazz Documentary - A Great Day In Harlem - Art Kane 1958 this probably is the greatest picture of that era of musicians I think ever taken and I'm so proud of it because now it's all over the United States probably the world very something like that it was like a family reunion you know being in one spot but all these great jazz musicians at one time I mean we call big dogs I mean the Giants were there press monk I looked around and it was count face charlie means guff Smith Jessica let's be jolly nice hit oh my my can you imagine if everybody had their instruments and played [Music] back in 1958 when New York was still the jazz capital of the world you could hear important music all over town representing an extraordinary range of periods of styles this film is a story of a magic moment when dozens of the greatest jazz stars of all time gathered for an astonishing photograph whose thing started I guess in the summer of 1958 at which time I was not a photographer art Kane went from this day to become a leading player in the field of photography this was his first picture it was our director of Seventeen magazine he was one of the two or three really great young art directors in New York attack Henry wolf and arcane and one or two other people were really considered to be big bright young Kurtz Robert Benton had not yet become a celebrated Hollywood filmmaker he had only just become Esquires new art director hoping to please his jazz fan boss with an idea for an all jazz issue but his inexperience combined with pains and experience gave -

Tina Tina 79 IMGSRCRU

1 / 3 Tina, Tina (79) @iMGSRC.RU a visual object or experience consciously created through an expression of skill or imagination. The term art encompasses diverse media such as painting, ...Missing: (79) | Must include: (79). Nov 9, 2013 — I actually found this Pumpkin Coffee Cake from Tina's Chic Corner BEFORE you all picked it as your favorite by clicking it ... 32x32-Stars-79-TW.. Jul 13, 2015 — As an account executive for CORnerstone Risk Solutions, a subsidiary of The IMA Financial Group, Tina will work with self- insured clients to .... Oct 12, 2013 — German Chocolate Cake Doughnuts from Tina's Chic Corner are a really great excuse to buy a doughnut pan. I mean ... 32x32-Stars-79-TW.. Place the table in the DIV with id="p2_out"> and after the table show: the state name with the .... .... Tina Turner: Tina Live! CD . ... Florence joined the District in 1992 as a physical education teacher at the Middle School. Tina McCauley, assistant principal at Lomond Elementary School since .... Matthijs (teambeurnaut) · Bitwala Security (team_bitwala) · Tina (teamblue) · Alan Barber (team-cadencelabs) · peter yaworski (teamcanada) · If Only Justin was .... Jul 10, 2007 — The sale was handled by Tina Adrian of Re-Max Classic in cooperation with Chris Kennedy of Charles Burt Homefolks. Randolph Brownell and .... Nov 21, 2017 — ... href="https://ru.atlassian.com/legal/customer-agreement" ... 20px;">. ... 79XybQdSii0f+Pyr5TosJDxoqIUV26jNO5NL60GfmmtYzO4TucVWUR5M/gnFeVbMl+ ... 1 Sep 2014 16:31:22 +0000 Reply- To: Tina Minchella Sender: ... from guest editors Zhi-Xue Zha= ng, (George) Zhen Xiong Chen, Ya-Ru Chen, and Soon Ang. ... target=3D"_blank">. Contributors: Essan Ni Jirman, Tina Brand, P.